Researching Genres in Agricultural Communities

The Role of the Farm Record Book

Abstract

While much of U.S. industry experienced increased productivity and economic vitality in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, agriculture was seen to lag behind and present an area open to change through reorganization, systemization, and science-based principles of production.1 The 1914 Smith-Lever Extension Act emerged from Congress with the goal of providing farmers with specialized education and standardized practices, setting the stage for agricultural knowledge to become a formalized sphere for technical and scientific inquiry. It was hoped that, just as progressive ideas had transformed the U.S. manufacturing economy, they would similarly reshape agricultural processes.

The period that produced Smith-Lever was an era of activism and optimism, and ideas of scientific and organizational advancement impacted all areas of the social and economic spectrum. The modernizing trends shaping farm production arose out of the ideologies of progressivism, and represented a response to rapidly changing social dynamics: industrialization, migration, a growing recognition of social disparities, and a growing faith in science and technology as pathways to a new, orderly, improved world.2 Political acts directed at farming signaled the increasing role of a federal bureaucracy that sought to control the development of the agricultural sector; these included the 1862 Morrill Act, which made possible the state land-grant colleges, and the 1887 Hatch Act, which funded experiment stations at the colleges.3 The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), which oversaw these institutions, also dates to 1862. The USDA “harnessed the scientific expertise of the Department” by “linking the public land grant colleges, farm groups, and individual farmers who participated in cooperative learning of new methods” through the creation of a public-private mission in the Smith-Lever extension service.4

The federal government, invested in the success of agricultural enterprises through the scientific and economic research produced in the land-grant colleges, experiment stations, and extension service, provided additional financial support in the form of the 1916 Federal Farm Act.5 While initially intended to facilitate greater production for World War I, this push to support the actual production processes of farming fit into a larger vision of social and economic rationality intended to boost the overall development of the country, and thus continued to expand after the war was won.6 The availability of financing allowed farmers to invest in land, machinery, and chemicals, and the new technologies led them to rely more and more on the institutions—the extension service, land-grant colleges, and experiment stations—that had been created to enable rapid modernization.7

The institution with the greatest immediate contact with farmers, the extension service, generated genres such as administrative forms and reports, research articles, educational brochures, and bookkeeping ledgers. In this context, genres—identifiable through form, content, and intent—are written texts recognizable as responses to recurring communication situations.8 Genres are intrinsically connected to social actions and relationships, an idea emerging from rhetorical genre theory.9 Genres help construct knowledge and transmit world views, shaping rhetorical situations; they are “one of the structures of power that institutions wield.”10 Some of these institutional genres had direct contact with, and effects upon, farming communities, and were thus able to influence farmers by establishing progressive ideas of education, improvement, and industry. In this paper, we argue that traces of these knowledge transmission efforts can be charted through the institutional promotion of the farm and 4-H record book genres, and that combining genre analysis with a targeted digital search interface can illuminate these traces.

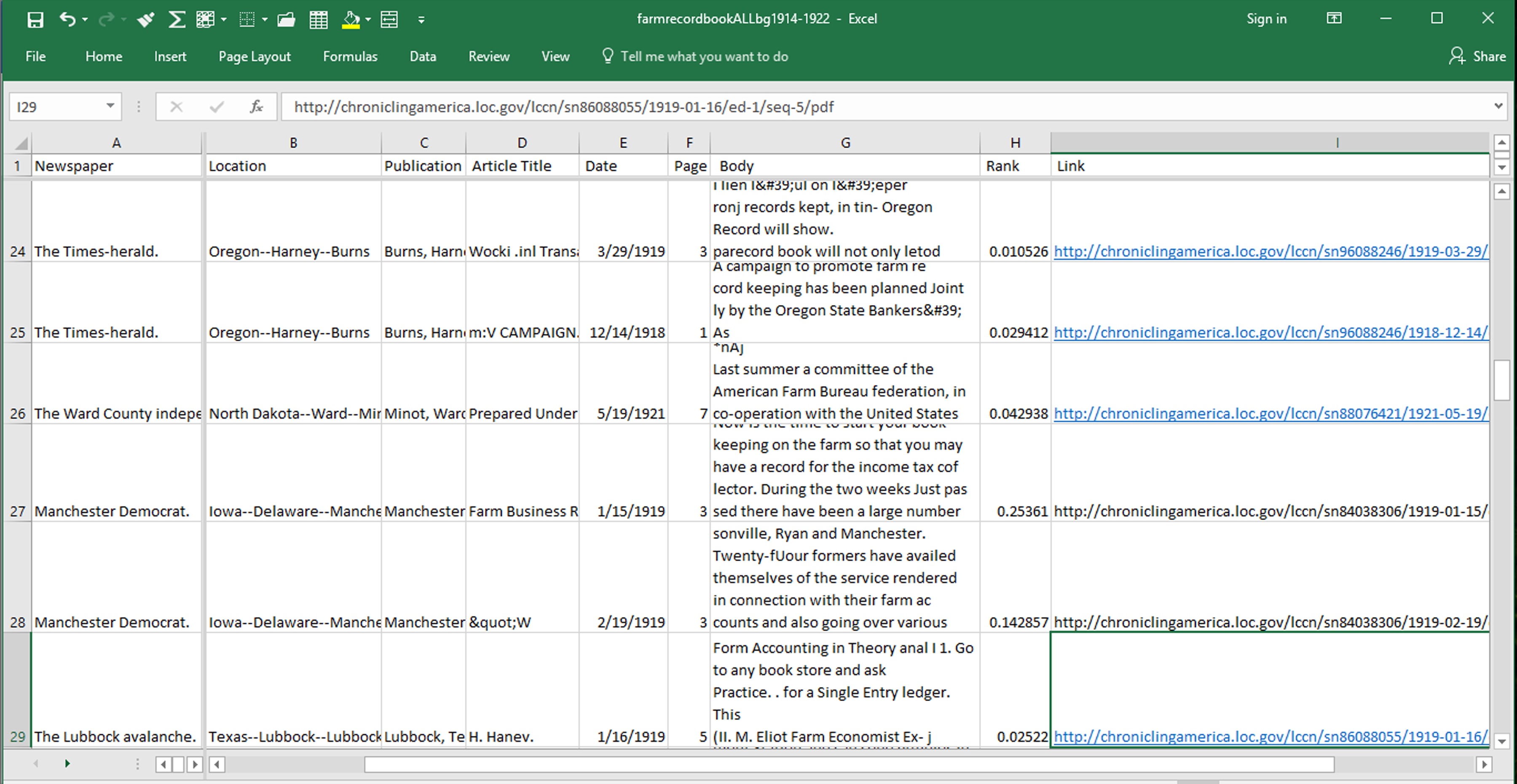

Signs of genre activity are apparent in both the physical and digital archives, as well as personal interviews. For this research we employed our project, Historical Agricultural News, or HAN, to improve the process of finding digitized newspaper sources in Chronicling America (ChronAm) through article-level searches.11 Our search tool enables users to filter agriculturally-related topics in digitized newspaper articles, so searches for the key term “record books” can be limited to an agricultural context. While we recognize this is not a perfect representation of data (not all newspapers have been digitized, and some existing digitized projects have poor quality machine readable text), it still provides a qualitative overview for analysis. HAN is delimited to a list of organizations we identified as a sub-dataset, with the primary goal of locating mentions of the extension service, land-grant colleges, and experimental farms. For our research, we performed an analysis of the times and contexts in which record books are mentioned in ChronAm newspapers, not a rhetorical analysis of actual record books.

The farm record book was a feature of progressive institutional involvement from early in the extension service program.12 Developed as a form of business ledger in conjunction with the USDA, the record book not only allowed farmers to formalize their processes, but also enabled the extension service to track their own influence in farming communities. The record book, which formalized the kinds of information farmers recorded, was both distributed and collected by the extension service and reported annually. Extension service reports were generated at district, state, and national levels, and the inclusion of farm record books in these reports indicate the value they represented as data-collection instruments.13

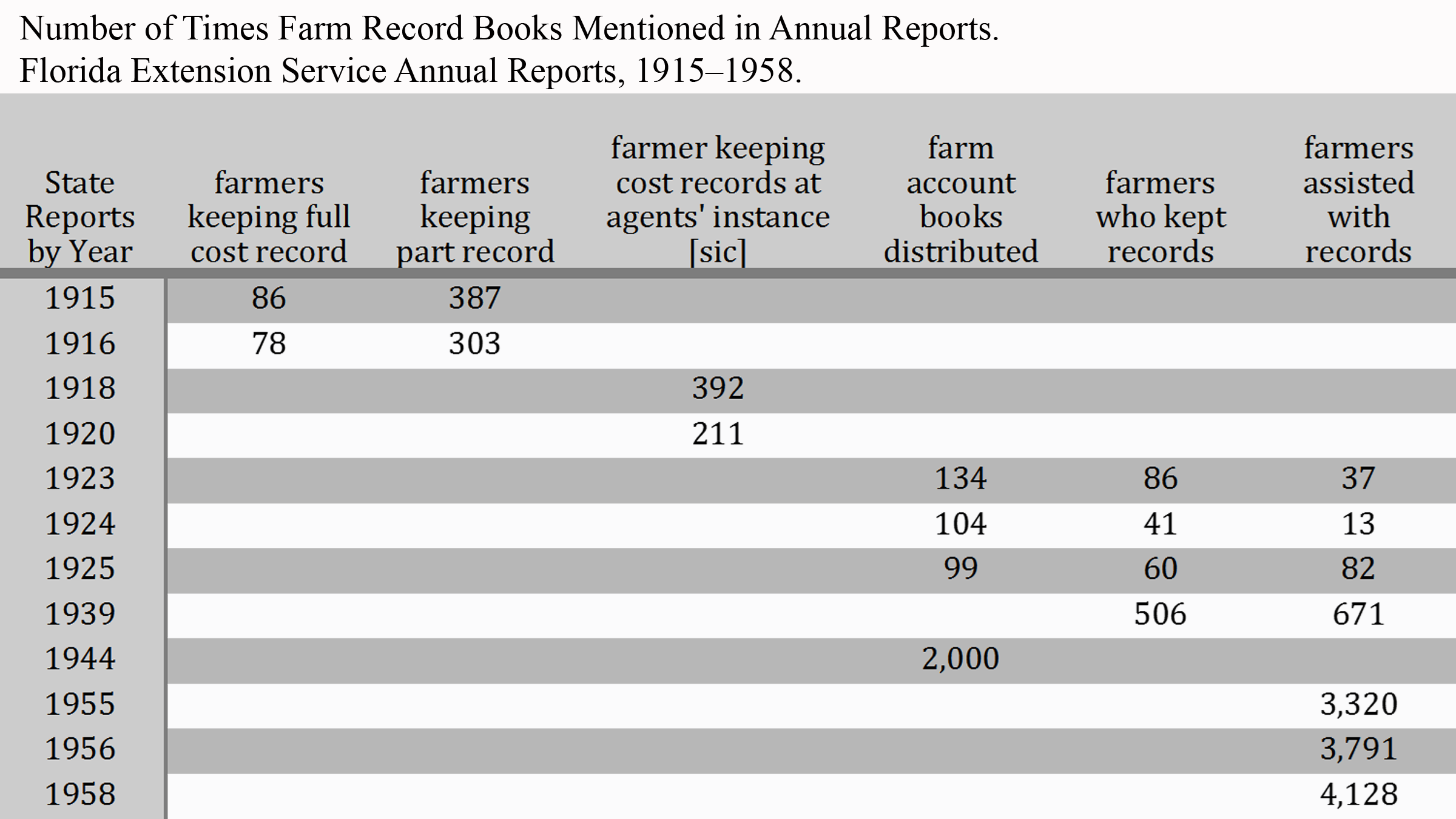

The table illustrates the mentions of record books in the annual Florida state reports.14 In the earliest reports, the agents note how many farmers keep either full or partial records of farm accounts. Later reports indicate that the agents actively assisted farmers with recording-keeping, and by the 1923 report,15 agents recorded how many books they handed out. The 1939 report16 shows a great jump in both quantities of books kept and of numbers of individuals assisted with accounting by extension service agents, and the narrative section in the 1944 report notes that

Farm record books have been supplied to more than 2,000 farmers and assistance has been given to many of them in entering inventories and otherwise posting their books. Noted improvement has been made by farmers in their record keeping during [the] 1944 Report as a result of their realization of the advantages to be obtained from accurate records when they compute income tax returns.17

Interpreting the spread of the farm record book from the perspective of genre as social action suggests it was transferring ideologies and over time influencing farmers to think of their farms in terms of business operations. However, in Galbreath’s earlier research and interviews with contemporary farmers on this topic, few were familiar with the books.18 The oldest interviewee, born in 1923, did remember them, and spoke of the record books in connection with his vocational agriculture classes in the 1940s. He noted that “you didn’t make enough money, but then you had to keep the books up to what you bought and spent, and [what you’re going to] make in advance, and then see what you really did make, and all that, which it’s a lot of government-type work . . . it doesn’t turn out too good with this weather.”19 From his perspective, the “bookwork” did not meet the reality of farming—the uncertainties of weather events and other uncontrollable forces of nature. Other interviews revealed the positive significance of genre participation in the youth arm of the extension service—the 4-H.20 These younger farmers, born and raised in a farming environment, still recalled the “new” knowledge they gained from 4-H work and the project records they kept, indicating that those related genres might also be communicating progressive world views.21

Prior research into the area of Boys and Girls Clubs and the 4-H acknowledge the importance of project records as learning and leadership exercises. In his 1951 history of the 4-H, Franklin M. Reck claims that the education gained from 4-H project work “ties learning to living with the closest possible bond,” with record books providing both mathematics and English practice.22 Tracy S. Hoover, et al. argue that the “learning and skill development” gained in these exercises indicate an “underlying philosophy that youth would also teach new agricultural practices to their parents.”23 Contextualizing 4-H learning as “hybrid literacies,”24 I. Moriah McCracken aligns the educational value of the record books with “bureaucratic (and adult) standards for discourse and literacy.”25 This view suggests similar motives as in the distribution of the adult farm record books, and she notes that the identification requests embedded in the forms assisted in national tracking.26

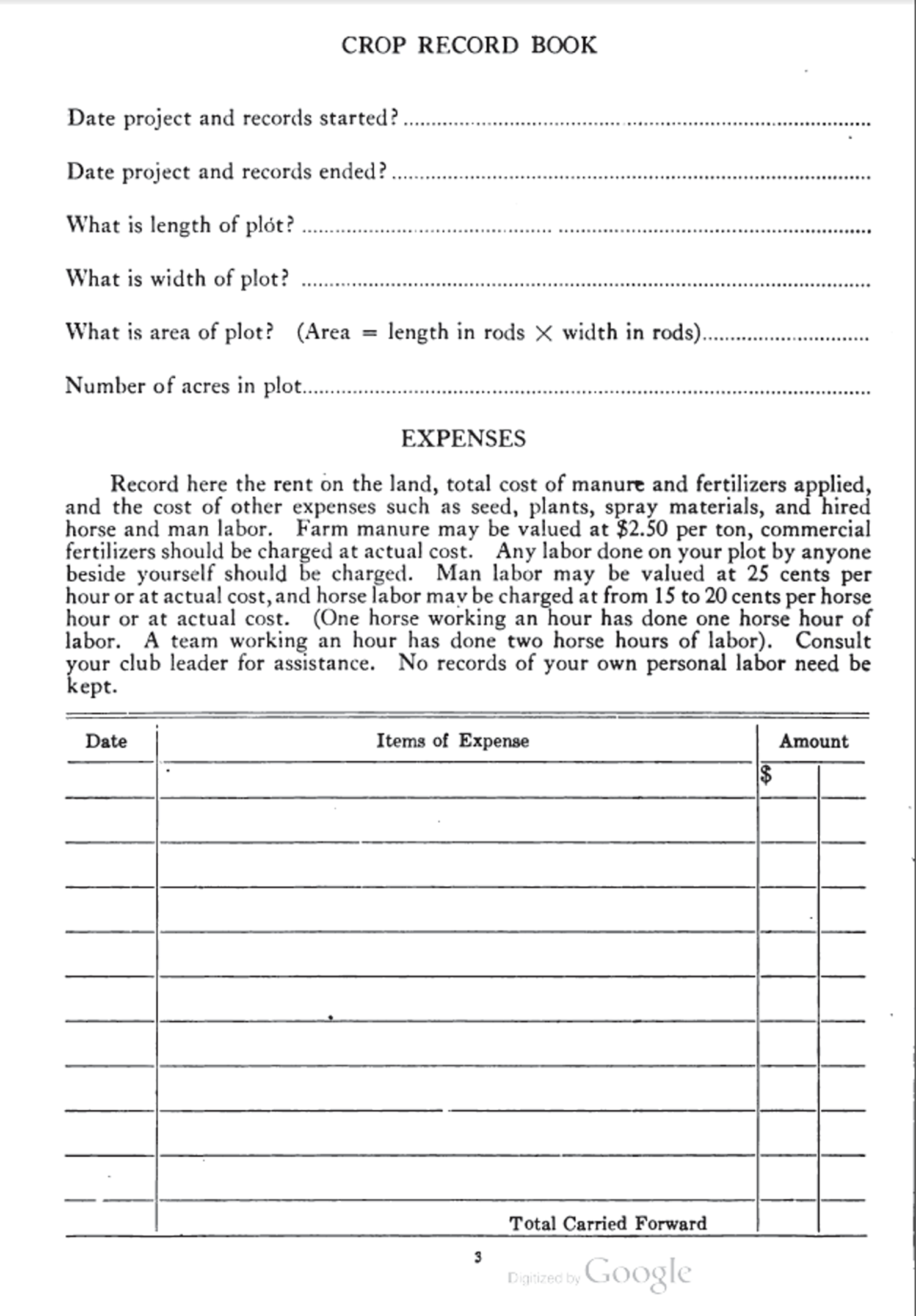

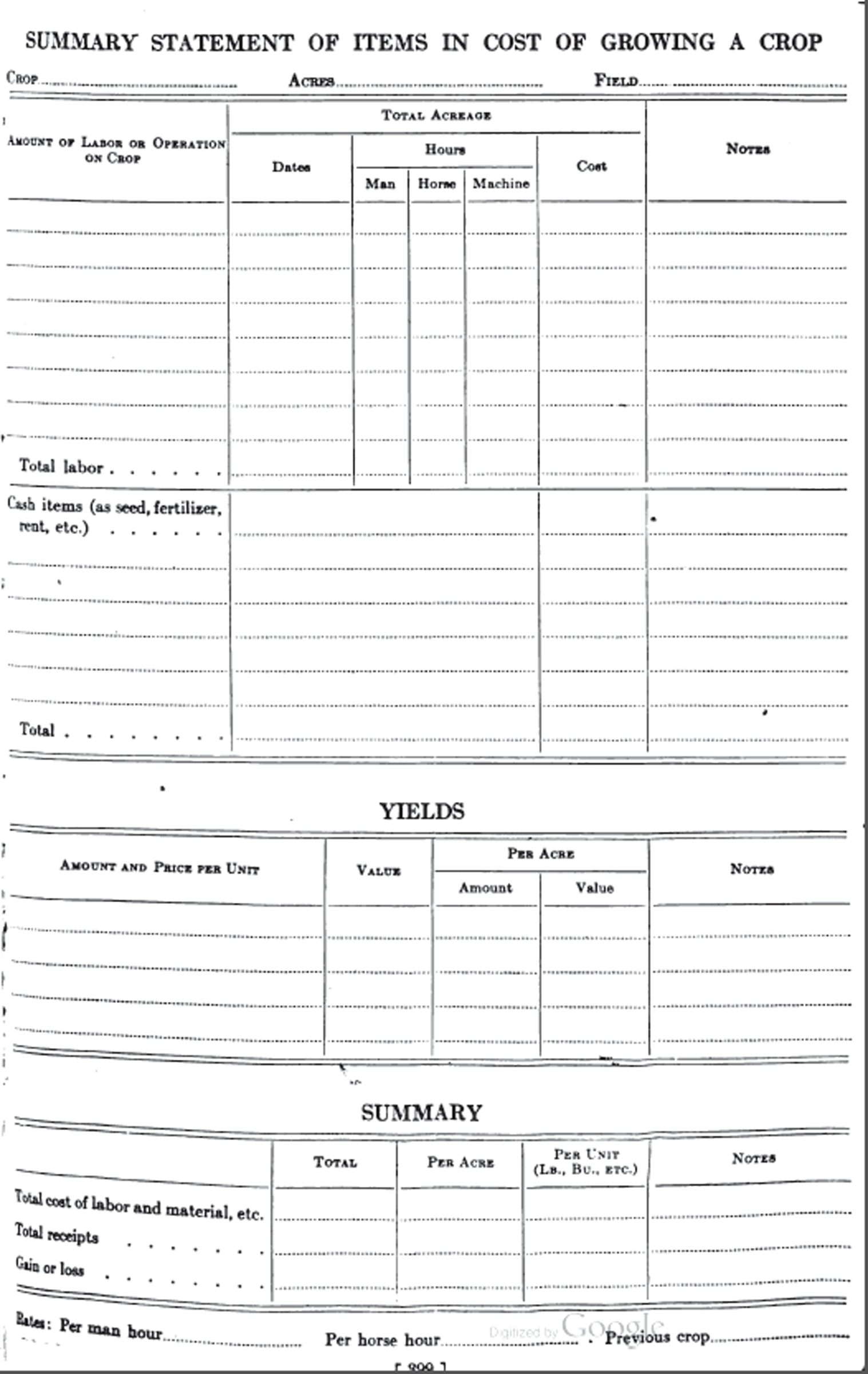

The project record is an introductory text, with simplified categories from the adult farm record ledgers, and early examples of both show the similarities in genre features. The layout and content for both the farm record book and the project record reflect the goal of having both youths engaged in club work and veteran farmers thinking about farming from an organizational perspective. But how did the extension service promote these genres, and how was this inculcation perceived at the local level?

Our research into these questions suggests that evidence of both farm records and project books is available in the ChronAm database. In the case of the farm record books, using HAN to search through all the organizations for the years 1836–1922 turned up 102 results, 76 of which had content specifically pertaining to farm record books.27 These were captured through a downloadable spreadsheet that contains citation information, the article text, and a link to the original newspaper page.

An example from a 1917 Norwich Bulletin article opens by stating “Farming is fast becoming recognized as a business and in order to realize the best possible returns it is necessary to have absolute knowledge of the business methods which apply to it.”28 Highlighting progressive thinking, the article proceeds to compare the successful farmer with a merchant and emphasizes the sad situation for farmers who “won’t try to know,” directing farmers to the local extension service for help getting started with the account book. Other articles indicate the importance the extension service placed on the record books for farm success, bank approvals, and income tax verification, and one carries a stern warning of lost work days and fines from “not furnish[ing] a proper report to the income tax collector.”29

Conducting a search with HAN for evidence of Boys and Girls Club project books, limiting organizations to Boys and Girls Clubs, and looking at the years 1836–1922, we found 34 articles that mentioned the key term “record” (the most prevalent reference to the project record book). We located references that demonstrated not only the use of project records, but also indicated how this idea was permeating the public consciousness. For example, an article from 1916 notes that “Through the keeping of accurate records of their operations the boys and girls receive training in farm management,” and “Not only are they beating their parents in production, but they are also stimulating their parents toward better farming methods and larger yields.”30 Other articles mention competitions, including county and state fairs, in which completed reports are a critical component of judging,31 and Boys and Girls Poultry Clubs, which were argued as a means to improve the poultry market in Florida and one of the requirements of which were “the keeping of accurate records of the amount of feed, labor, number of eggs produced, chickens raised, marketed, etc.”32

As a genre, the project record brought the “new” knowledge the young people learned in their Boys and Girls Clubs (and later 4-H) activities together with their community farming experiences, shaping their perspective of farming as a business and a viable career choice. As argued in a 1922 article,

If we can get them interested in the beauties of nature, the wonders of plant and animal life; if we will go a step further and show them the possibilities for profit, for making money in agricultural pursuits, we can win them to the farm and keep them there, to the great benefit of themselves and the country. A way has been found to do this through the medium of the boys’ and girls’ club work.33

Young farmers learned confidence, organizational skills, and other leadership qualities from their transitional experiences in the youth agricultural organizations supported by the extension service. The professional farmer identities they gained there were not in opposition to the community dialogues and understandings with which they grew up, but were structured in a way that supported the goals of the extension service and all the institutions with which it aligns: the experiment stations, the land-grant college, and the USDA. The progressive ideologies transmitted through the social action of these genres, like the processes transferred through the project record, are not always visible, but nonetheless helped shape modern agricultural practices and our understanding of them.

Bibliography

Agricultural Extension Service. Annual Report, 1923: Report of General Activities for 1923 with Financial Statement for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1923. Gainesville: University of Florida, Florida State College for Women, and United States Department of Agriculture, 1923.

Agricultural Extension Service. Florida Agricultural Extension Service 1944 Report. Gainesville: University of Florida, Florida State College for Women, and United States Department of Agriculture, 1944.

Agricultural Extension Service. Silver Anniversary Report, Florida Agricultural Extension Service Annual Report 1939. Gainesville: University of Florida, Florida State College for Women, and United States Department of Agriculture, 1939.

Bawarshi, Anis S. and Mary Jo Reiff. Genre: An Introduction to History, Theory, Research, and Pedagogy. West Lafayette: Parlor Press, 2010. WAC Clearinghouse. https://wac.colostate.edu/books/referenceguides/bawarshi-reiff/.

Bazerman, Charles. “Speech Acts, Genres, and Activity Systems: How Texts Organize Activity and People.” In What Writing Does and How It Does It: An Introduction to Analyzing Texts and Textual Practices, edited by Charles Bazerman and Paul Prior. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2004.

Bensel, Richard Franklin. The Political Economy of American Industrialization, 1877–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511665004.

Chickasha Daily Express (Chickasha, OK). “Good Record Made by Grady County Agent.” November 15, 1916. Chronicling America. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86090528/1916-11-15/ed-1/seq-1/pdf.

The Commission on Country Life. Report of the Country Life Commission. New York: Sturgis & Walton, 1917. https://archive.org/details/reportofcommissi00unitiala.

Crossville Chronicle (Crossville, TN). “Capt. Peck Talks About Boys’ and Girls’ Club Work.” November 8, 1922. Chronicling America. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85042757/1922-11-08/ed-1/seq-4/pdf.

Denison Review (Denison, IA). “Good Start in Club Work.” May 29, 1918. Chronicling America. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84038095/1918-05-29/ed-1/seq-6/pdf.

The DeSoto County News (Arcadia, FL). “Plans of Poultry Club Work in Florida.” September 28, 1916. Chronicling America. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn95026908/1916-09-28/ed-1/seq-8/pdf.

Devitt, Amy J. Writing Genres. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004.

Ferleger, Louis. “Arming Agriculture for the Twentieth Century: How the USDA’s Top Managers Promoted Agricultural Development.” Agricultural History 74, no. 2 (2000): 211–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3744848.

First Morrill Act, 7 U.S.C. § 301 (1862). https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=33.

Fitzgerald, Deborah. Every Farm a Factory: The Industrial Ideal in American Agriculture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

Freedman, Aviva and Natasha Artemeva. “Introduction.” In Rhetorical Genre Studies and Beyond. Winnipeg: Inkshed Press, 2008.

Galbreath, Marcy L. “Sponsors of Agricultural Literacies: Intersections of Institutional and Local Knowledge in a Farming Community.” Community Literacy Journal 10, no. 1 (2015): 59–72.

Galbreath, Marcy L. “Tractors and Genres: Knowledge-Making and Identity Formation in an Agricultural Community.” PhD diss., University of Central Florida, 2014.

Gregg, Sara. “From Breadbasket to Dust Bowl: Rural Credit, the World War I Plow-Up, and the Transformation of American Agriculture.” Great Plains Quarterly 35, no. 2 (2015): 129–66. https://doi.org/10.1353/gpq.2015.0025.

Hoover, Tracy S., Jan F. Scholl, Anne H. Dunigan, and Nadezhda Mamontova. “A Historical Review of Leadership Development in the FFA and 4-H.” Journal of Agricultural Education 48, no. 3 (2007): 100–10.

Keathley, Clarence R., and Donna M. Ham. “4-H Club Work in Missouri.” Missouri Historical Review 71, no. 2 (1977): 193–203.

Manchester Democrat (Manchester, IA). “Delaware County Farm Bureau.” January 15, 1919. Chronicling America. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84038306/1919-01-15/ed-1/seq-3/pdf.

McCracken, I. Moriah. “‘I Pledge My Head to Clearer Thinking’: The Hybrid Literacy of 4-H Record Books.” In Reclaiming the Rural: Essays on Literacy, Rhetoric, and Pedagogy, edited by Kim Donehower, Charlotte Hogg, and Eileen E. Schell, 121–42. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2011.

Miller, Carolyn R. “Genre as Social Action.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 70, no. 2 (1984): 151–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335638409383686.

Miller, Carolyn R. “Rhetorical Community: The Cultural Basis of Genre.” In Genre and the New Rhetoric, edited by Aviva Freedman and Peter Medway, 67–78. London: Taylor and Francis, 1994.

Norwich Bulletin (Norwich, CT). “Extension Service of State College Ready to Give Help.” November 1, 1917. Chronicling America. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014086/1917-11-01/ed-1/seq-9/pdf.

Reck, Franklin M. The 4-H Story: A History of 4-H Club Work. Ames, IA: Iowa State College Press, 1951.

Rodgers, Daniel T. “In Search of Progressivism.” Reviews in American History 10, no. 4 (1982): 113–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2701822.

Russell, David R. “Rethinking Genre in School and Society: An Activity Theory Analysis.” Written Communication 14, no. 4 (1997): 504–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088397014004004.

Sanders, Elizabeth. “Rediscovering the Progressive Era.” Ohio State Law Journal 72, no. 6 (2011): 1281–94. http://hdl.handle.net/1811/71472.

St. Johnsbury Caledonian (St. Johnsbury, VT). “Maine Schoolboys Are Getting Record Crops.” May 3, 1916. Chronicling America. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84023253/1916-05-03/ed-1/seq-7/pdf.

Trace, Ciaran B. “Information in Everyday Life: Boys’ and Girls’ Agricultural Clubs as Sponsors of Literacy, 1900–1920.” Information & Culture 49, no. 3 (2014): 265–93. https://doi.org/10.7560/IC49301.

United States Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture. “The Hatch Act of 1887.” https://nifa.usda.gov/program/hatch-act-1887.

Worster, Donald. Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s. 1979. Reprint, New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Notes

-

The deficiencies of agricultural production were pointed out in Theodore Roosevelt’s Report of the Country Life Commission, which was sent to Congress in 1909. The report highlighted the problem for the economy in general if farm work was not brought up to the efficiencies in other sectors. ↩

-

Rodgers, “In Search of Progressivism”; Sanders, “Rediscovering the Progressive Era.” Rodgers argues that “those who called themselves progressives did not share a common creed or a string of common values, but they used three “distinct social languages—to articulate their discontents and their social visions.” These were “the rhetoric of antimonopolism,” “an emphasis on social bonds and the social nature of human beings,” and “the language of social efficiency” (123). The language of social efficiency, with “schemes to reorganize government on business lines,” by extension imparted business methods into everything government touched—including agriculture (126). Sanders contends that, while progressives had varying political alliances, “they shared an assumption of linear progress; progressives could be said to be modernization theorists” (1282). ↩

-

First Morrill Act, 7 U.S.C. § 301; United States Department of Agriculture, “The Hatch Act of 1887.” ↩

-

Sanders, “Rediscovering the Progressive Era,” 1291. ↩

-

Gregg, “From Breadbasket to Dust Bowl”; Worster, Dust Bowl. Gregg points out that those involved in expanding agricultural production—“farmers, businessmen, and government officials”—were of a mind that modernization was critical to the country, and thus supported the “altered relationship” the Farm Act represented. She asserts “These new practices brought increased efficiency and the maximization of resources, and most Americans embraced them as the benefits of a modernizing age, not anticipating the unintended economic and ecological consequences of these policies” (129–30). Worster writes about the effects of the expansionist thinking and rhetoric that led to overdevelopment of the Great Plains, a utilitarian perspective in which the dominant philosophy underlying modernization was capitalism (7). ↩

-

Bensel, The Political Economy of American Industrialization; Fitzgerald, Every Farm a Factory. Bensel makes the claim that the “rapid industrialization” the U.S. saw after the Civil War and into the turn of the century was a product of “inseparably and intimately interconnected” political and economic development processes (17). He observes that these processes exacerbated demographic differences between an industrial north and mainly agricultural south. Fitzgerald argues that the changes urged upon agriculturalists represented “an industrial logic” that linked capital, raw materials, transportation networks, communication systems, and newly trained technical experts” into interlocking webs (3). ↩

-

Ferleger, “Arming Agriculture for the Twentieth Century,” 212. ↩

-

Miller, “Genre as Social Action,” 151–67. Miller was the first to frame recurrent texts occurring in everyday rhetorical situations as participants in social action, arguing that the writing not only responds to situational needs and constraints, but actively shapes situations of which the genres are an inherent part. ↩

-

Bazerman, “Speech Acts, Genres, and Activity Systems,” 309–39. Rhetorical genre theory builds on Miller’s argument for using texts to understand social interactions. Bazerman argues that “people using text create new realities of meaning, relation, and knowledge,” and a text that performs as intended “creates for its readers a social fact” (309–11). Also see Devitt, Writing Genres; Bawarshi and Reiff, Genre: An Introduction; Freedman and Artemeva, “Introduction,” in Rhetorical Genre Studies; and Russell, “Rethinking Genre,” 504–54. ↩

-

Miller, “Rhetorical Community,” 71. ↩

-

Examples and explanations of possible research applications in Historical Agricultural News can be seen at http://ag-news.net. ↩

-

Trace, “Information in Everyday Life.” Trace includes record books as “part of the toolkit of the progressive farmer, and the importance of recordkeeping from a scientific and business perspective was being promoted by interested parties, including agricultural colleges, the USDA, bankers’ associations, and the farm press” (269). ↩

-

Galbreath, “Sponsors of Agricultural Literacies,” 64. ↩

-

Galbreath, “Tractors and Genres,” 105. ↩

-

Agricultural Extension Service, Annual Report, 1923. ↩

-

Agricultural Extension Service, Silver Anniversary Report. ↩

-

Agricultural Extension Service, Florida Agricultural Extension Service 1944 Report, 24. ↩

-

The community Galbreath researched for her dissertation, Samsula, Florida, was settled in the early twentieth century primarily by immigrants from Slovenia and other eastern European countries who were attracted to the area by advertisements for affordable, newly-drained farm land. Their descendants were the subjects of Galbreath’s interviews. ↩

-

Bob Jontes, interview by Galbreath, May 28, 2012. ↩

-

Galbreath, “Sponsors,” 65. ↩

-

Trace, in researching 4-H project records, points to “their origins in the project method, championed by progressive educators, and in the early-twentieth-century extension practices of the USDA” (276). ↩

-

Reck, The 4-H Story, 213. ↩

-

Hoover, et al., “A Historical,” 102. One of the issues the 4-H met, according to Keathley and Ham, was the difficulty the land-grant colleges had in persuading adult farmers to “try the new promising methods and practices.” Keathley and Ham, “4-H Club Work in Missouri,” 193. ↩

-

McCracken, “‘I Pledge My Head to Clearer Thinking’,” 132. While McCracken does not specifically mention genre theory, her insights support the idea that the project record book participated in the social action of conveying progressive and institutional farming ideas by grooming young agriculturalists for a business model ideology of farming. ↩

-

Ibid., 126. ↩

-

Ibid., 127. ↩

-

Historical Agricultural News was created as a response to the 2016 National Endowment for the Humanities Chronicling America Data Challenge. Copyright laws and the contents of Chronicling America constrained HAN’s website and data, limiting the date range from 1836 to 1922 and to only those papers within ChronAm at the time the current dataset was created (ChronAm has since expanded their date range). The project’s article parser created the standalone HAN dataset by extracting articles from ChronAm which specifically contained agricultural organization terms (agricultural co-operative, boys and girls clubs, country life commission, experiment station, extension service, farm bureau, farm organization, horticultural society, land-grant colleges, and agricultural supply company). Additionally, since the HAN dataset is restricted to agricultural organizations, only if an article discussing farm record books also included an agricultural organization would it have been pulled into the HAN dataset to be available for this current research. The date range for this paper was further limited as the legislative acts which created the extension service and formalized the use of farm record books began in 1914. ↩

-

Norwich Bulletin, “Extension Service of State College.” ↩

-

Manchester Democrat, “Delaware County Farm Bureau.” ↩

-

St. Johnsbury Caledonian, “Maine Schoolboys Are Getting Record Crops.” ↩

-

Chickasha Daily Express, “Good Record Made by Grady County Agent”; Denison Review, “Good Start in Club Work.” ↩

-

The DeSoto County News, “Plans of Poultry Club Work in Florida.” ↩

-

Crossville Chronicle, “Capt. Peck Talks About Boys’ and Girls’ Club Work.” ↩

Appendix

Authors

Marcy L. Galbreath,

Department of Writing and Rhetoric, University of Central Florida, marcy.galbreath@ucf.edu,