Race and Place

Dialect and the Construction of Southern Identity in the Ex-Slave Narratives

Abstract

From 1936 to 1938, interviewers sat on porches, in living rooms, and at kitchen tables asking black citizens about their lives under chattel slavery and after emancipation. These writers were employees of the federal government’s Work Progress Administration’s Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), a New Deal organization designed to support cultural workers through employment. Who and how people were represented in the FWP’s writings shaped inclusion, citizenship, and national identity.1 The stakes were high as cultural and political struggles ensued over the identity and future of a nation in the throes of a Great Depression, while simultaneously debating the meaning and memory of the antebellum era during the 75th anniversary of the Civil War.2

Historian Jerrold Hirsch argues that the FWP’s goal was to celebrate American pluralism in order to depict a nation culturally rich because of its diversity and heterogeneity.3 The project exemplar was the State Guide Series—a collection of books focused on the history, culture, and people of each state—designed to be a “portrait of America”. Lesser known are a plethora of projects concerned with documenting the lives of citizens in their words through narrative, often called life histories. The rationale for these projects differed from those of the Guide Series. Of primary concern was cultural and historical knowledge that was understood as disappearing due to assimilation into modernity, such as folk culture including folklore and ballads, or because those who remembered historical events were passing, such as the stories and experiences of the generation that had lived during chattel slavery and emancipation. FWP administrators, such as national folklore editor John Lomax, were not concerned with pluralism, but rather with saving folkways and memories that were perceived to be vanishing.4

Among the most prominent and debated life histories are the Ex-Slave Narratives.5 FWP interviewers—most of whom were white and over half women—documented the narratives of over 2,400 formerly enslaved people.6 Using a script of questions as their guide, interviewers asked about life during chattel slavery. Throughout the tenure of the project, they added questions about life following emancipation and folklore.7 The interviews were transcribed from memory and field notes and then revised by state and national editors. Where the interview was conducted, which questions were emphasized, and how answers were documented shaped the narratives.

The conditions that created the Ex-Slave Narratives has led to ongoing scholarly debates about exactly what historians can learn.8 Benjamin Botkin, FWP national folklore editor from 1938-1939, released Lay My Burden Down in 1945 to explain the importance of the interviews, yet interest in the book was minimal. The rise of the new social history alongside the black liberation struggle ignited interest in reassessing the history of slavery. Historians rediscovered the Ex-Slave Narratives in the 1970s. Debates ensued about the narrative’s authenticity. Scholars have argued that the narratives are empirical evidence of black life from the mid-1800s to the 1930s. Others have called for their complete dismissal as unreliable and a white-washing of the black experience.9 In other words, a fiction constructed by white writers and editors invested in diminishing the violence of chattel slavery and improvements post-emancipation in order to perpetuate Lost Cause narratives and question black citizens fitness for citizenship.10 More recent scholarship—informed by work on oral history and the ethnographic encounter as a site of negotiation shaped by each person’s positioning—complicates the facile categorization of the narratives as either truth or fiction.11

Catherine Stewart’s influential 2016 book Long Past Slavery exemplifies the shift. She focuses on how social knowledge produced at the intersection of oral history and ethnography can illuminate historical knowledge about the 1930s. The Ex-Slave Narratives, she argues, became a site to negotiate black people’s right to full citizenship and to be a part of the nation’s identity. Writers used memories of slavery and life post-emancipation as well as the ways they transcribed the interviews as arguments for and against African Americans’ fitness to be full citizens. The subjectivity of the interviewer, the questions posed, responses from interviewees, and the ways the stories were written shaped the narratives, which became a contested space to assert or de-legitimize black selfhood and therefore rights to full incorporation into the nation.12

The narratives therefore risked reifying the antebellum social order, a segregated underclass managed and contained by middle- and upper-class whites. If the promises of emancipation were control over one’s life, the narratives were anything but in their control. Such conditions do not mean that those interviewing weren’t earnest in their intentions to listen, or that interviewees didn’t make room or assert agency through practices such as signifying, as Stewart argues.13 However, like emancipation, full control over their own lives was as partial as their ability to speak for themselves in these interviews.

Among the most contentious issues is the use of dialect. Interviewers were instructed to capture the words of the interviewee. As FWP’s Associate Director George Cronyn wrote, “While it is desirable to give a running story of the life of each subject, the color and human interest will be greatly enhanced if it is told largely in the words of the person interviewed. The peculiar idiom is often more expressive than a literary account.”14 Yet, exactly how to represent local and regional variations of language in writing was a thorny project.

In response, John Lomax, Folklore Editor from 1936 to 1937, developed a “negro dialect” to represent black vernacular speech patterns.15 He set out to standardize how local variations would be written. For example, dialect words such as “de” or “dat” were spelled without an “h” because the letter was considered unnecessary, and words like “poe” was not to be used for “po’ (poor).” 16 As a result, FWP writers flattened regional variations into a single speech style intended to represent all black oral traditions across the U.S.17

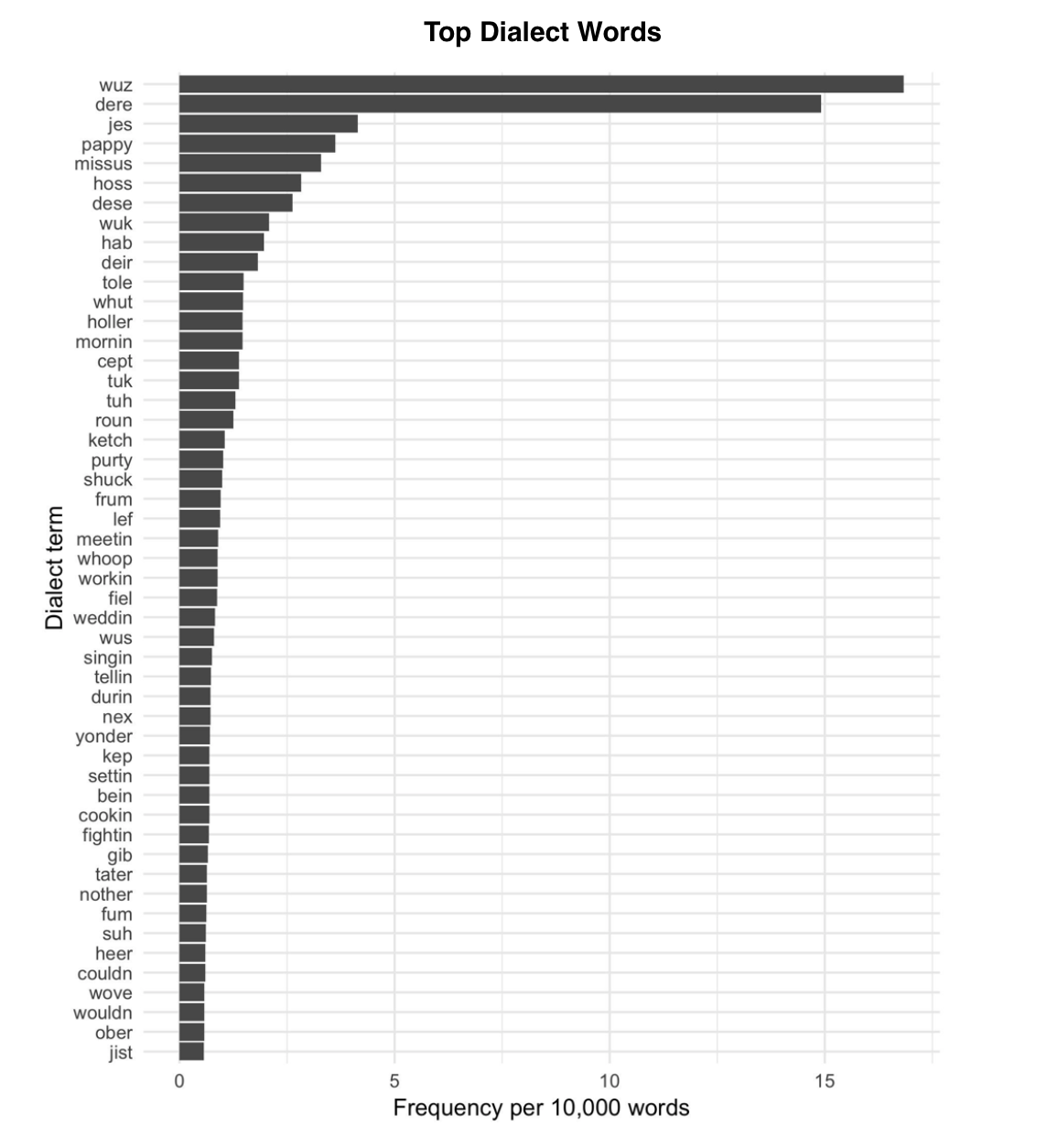

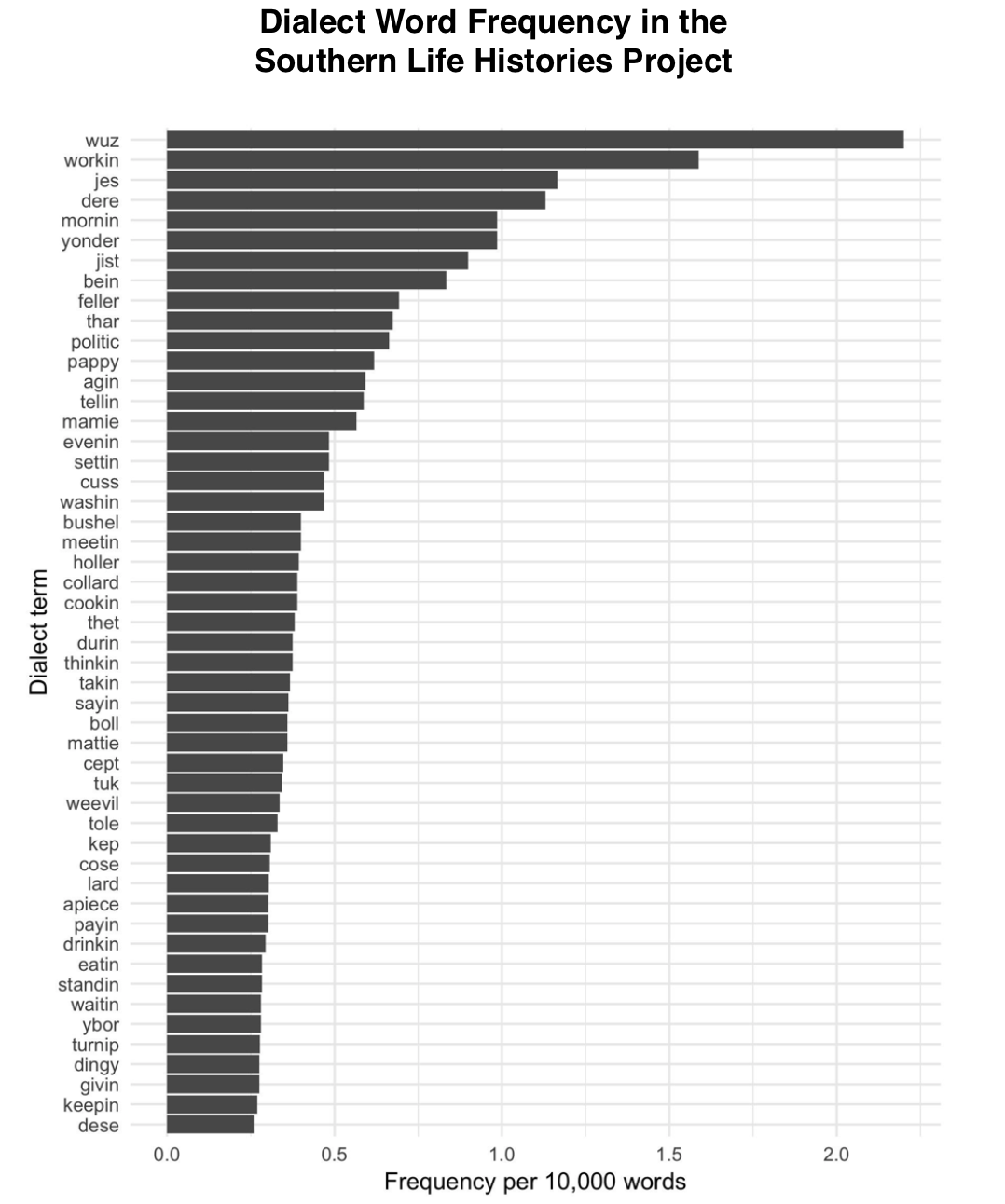

Text analysis reveals which words were most indicative of dialect. In order to identify dialect terms, the Ex-Slave Narratives were converted to plain text files using the WPAnarratives R package created by Lincoln Mullen, and words not found in a standard english word list were isolated. The top 120 remaining words were then manually labeled and filtered to detect 92 dialect terms. Frequencies of the most common dialect terms are shown in Figure 1. Words such as “wuz” (in lieu of “was”) and “dere” (in lieu of “there”) were the most used.

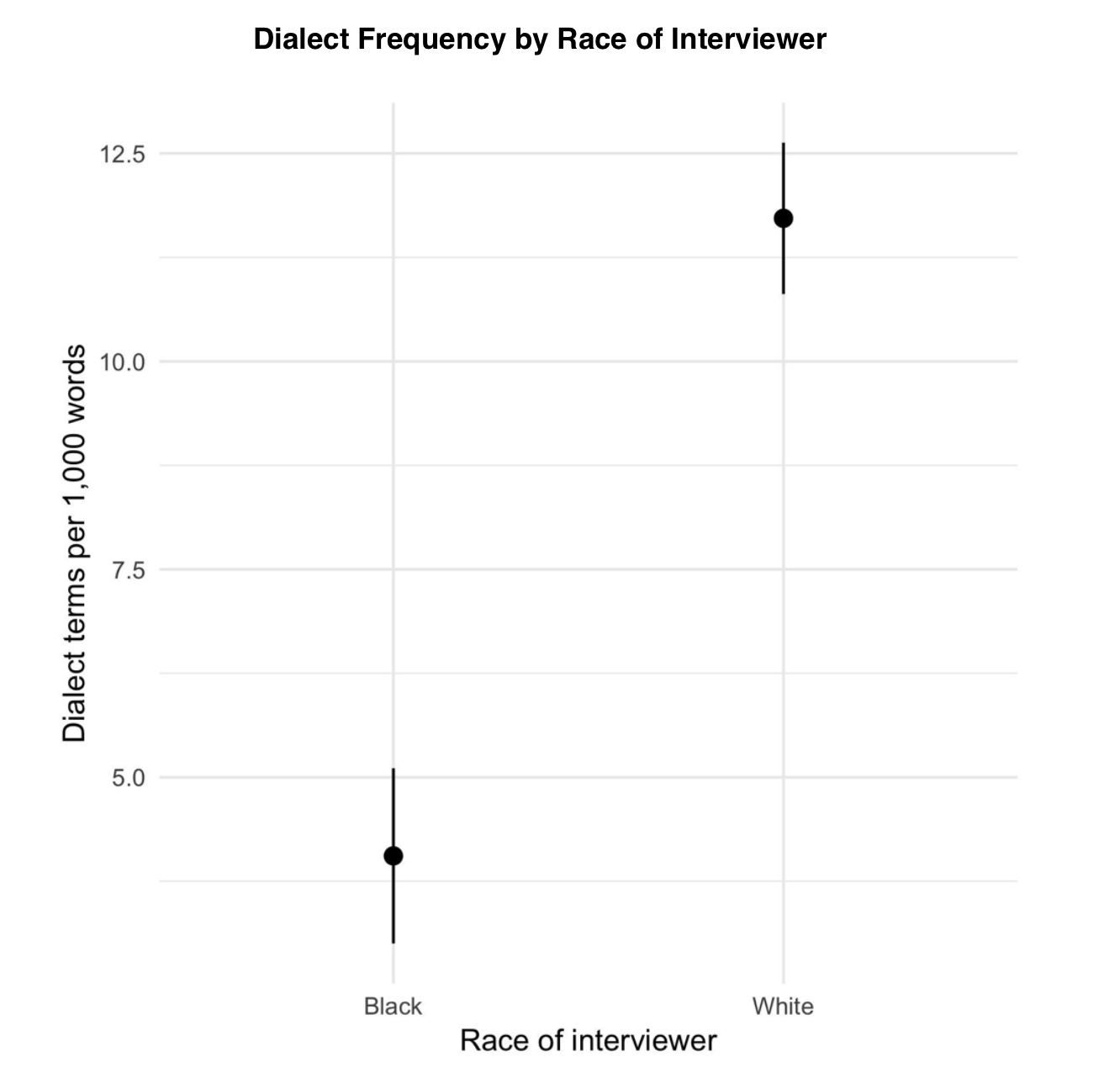

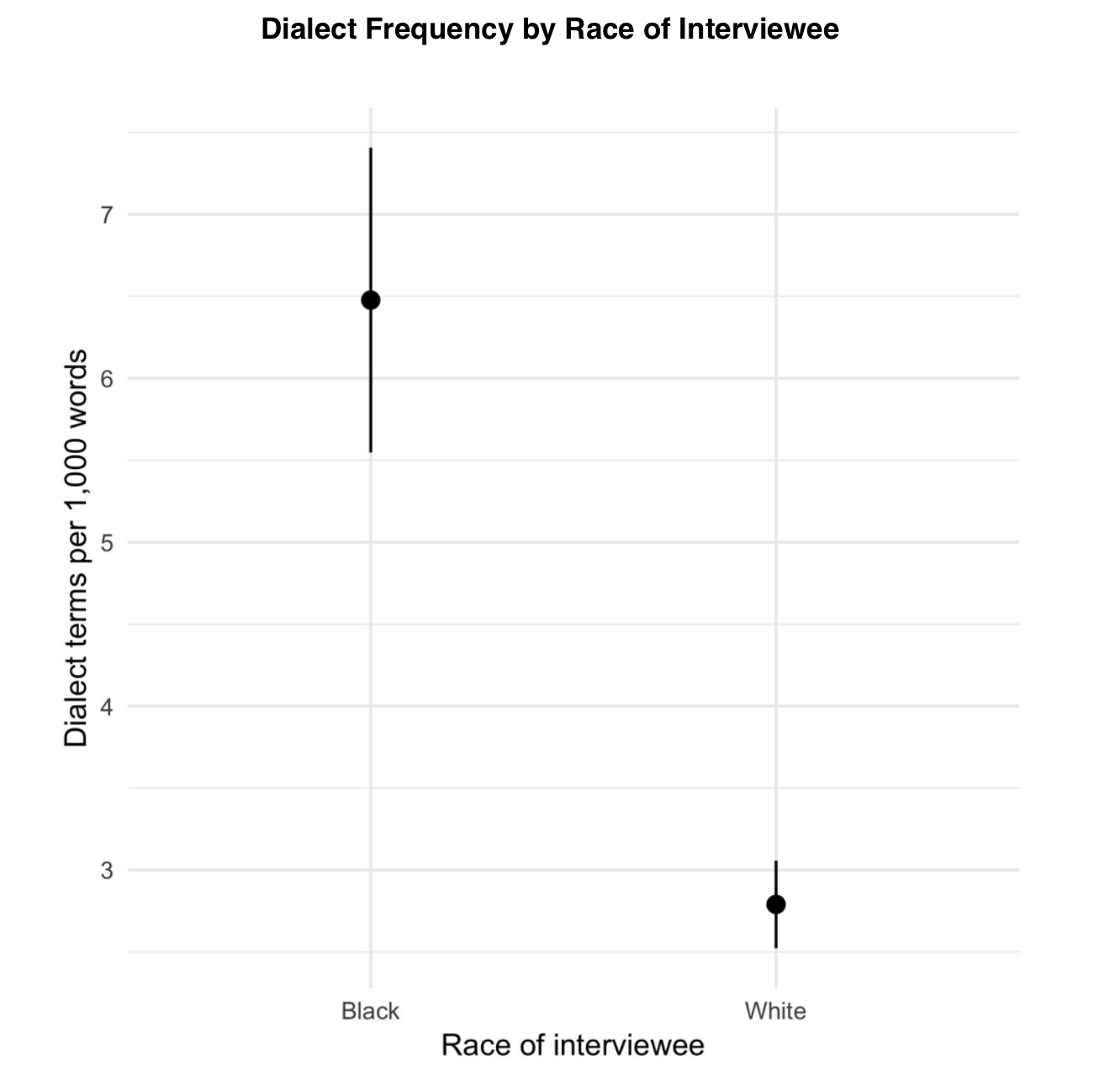

Next, the extent of dialect in the collection was compared to the race of the interviewer (Figure 2). After identifying the top 100 words indicative of dialect, they were queried across the corpus of 2,400 interviews from the Library of Congress. The percentage of dialect in each life history was calculated. Each life history was then categorized by the race of the interviewer. White interviewers were significantly more likely to use dialect. Mary Hicks of North Carolina, Watt McKinney of Arkansas, and Annie Ruth Davis of South Carolina used the most dialect words. The findings extend Stewart’s argument—that dialect was used more by white interviewers from a subset of Florida and Georgia —to the entire collection.18

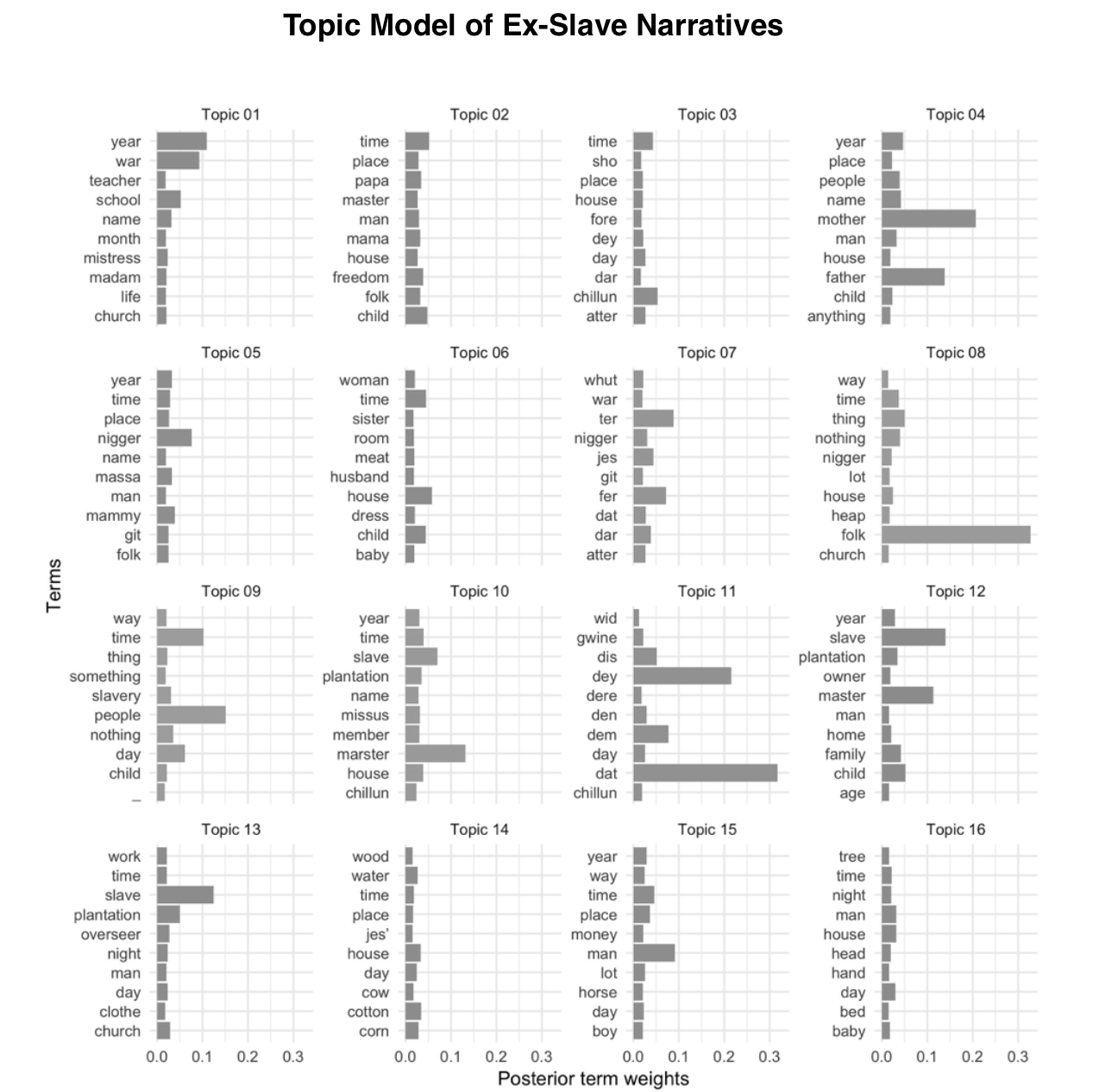

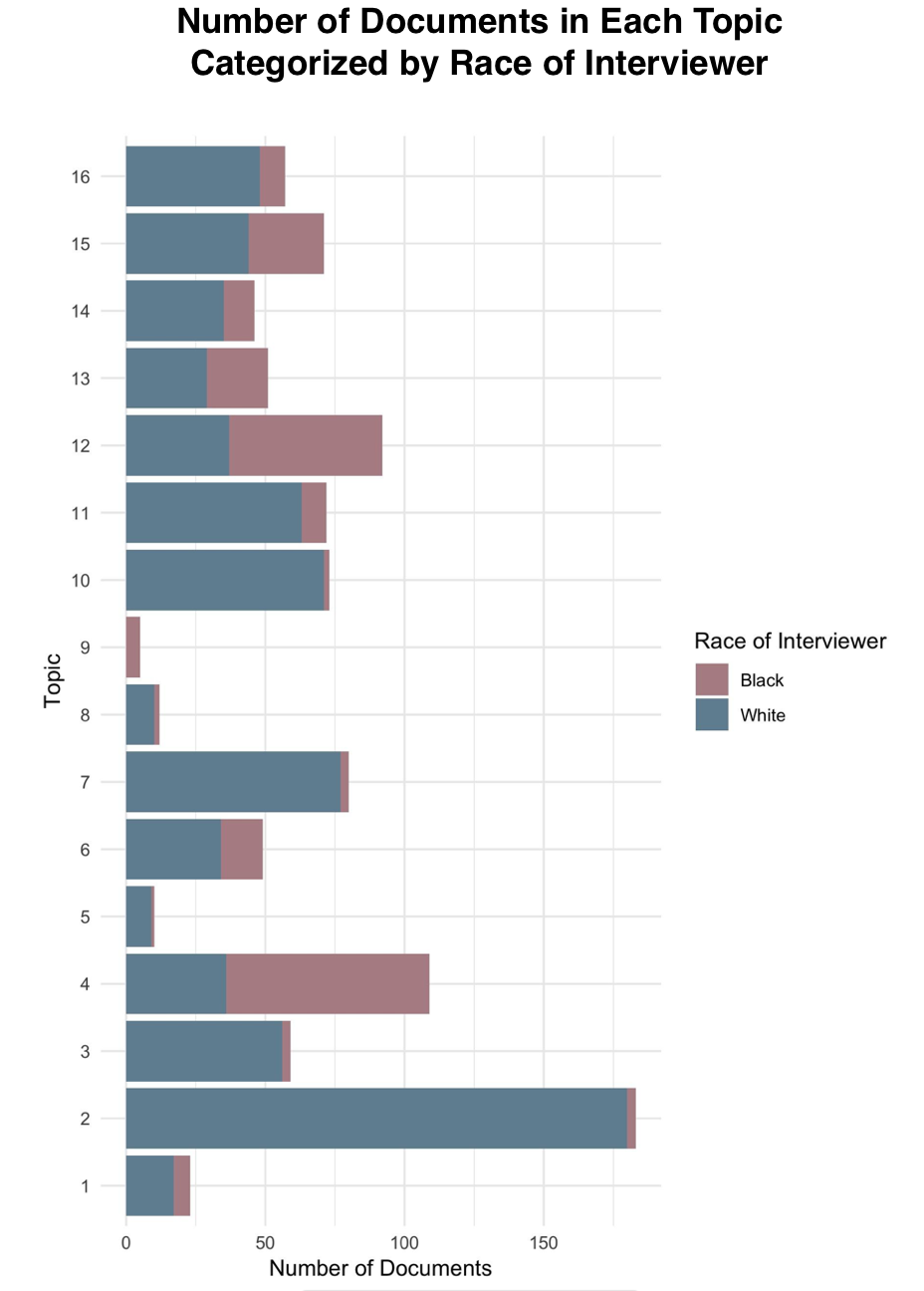

Topic modeling, which identifies themes and discourses in the collection, also confirmed that dialect was prominent among white interviewees. Along with returning topics about family life and farming during slavery, the topic model returned clusters of words comprised almost entirely of dialect words such as Topic 11 (Figure 3). Topic models therefore also reveal rhetorical strategies. The topics indicate that using “negro dialect” was not only a pattern but a strategy for constructing racialized subjectivities.19

Importantly, certain topics were more likely to be used by white interviewers than black interviewers and vice versa (Figure 4). For example, Topic 7 is mostly dialect words and far more prominent in interviews conducted by white writers. On the other hand, Topic 12, which discusses interviewees relationship to their “family” and “master”, is devoid of dialect words, and more prominent in interviews led by black interviewers.

The call for a “negro dialect” served two purposes, Stewart argues. First, dialect signaled authenticity. White FWP workers argued that the interviews truly represented black voices since the style of speech aligned with common stereotypes of black vernacular speech patterns. Second, the FWP planned to publish the narratives for a primarily white audience. Their market hopes were not unfounded since slave narratives circulated within the abolitionist press for almost a century and the 1930s literary markets produced a significant interest in Southern life.20 Too much variation in dialect would make them too difficult to read. Cronyn captured this duality in his instructions to state directors. He wrote, “This does not mean that the interviews should be entirely in ‘straight English’—simply, that we want to be more readable to those uninitiated in the broadest Negro speech”.21

Local or regional variations in speech patterns were dismissed in the service of a homogenous, singular black dialect constructed by John Lomax and his white colleagues for white audiences. Race, therefore, became a linguistic feature used primarily by white interviewers argues Stewart.22 Because formerly enslaved peoples were represented as speaking in the same racialized dialect, the narratives served as a form of “othering.” The use of dialect in Ex-Slave Narratives simultaneously signaled authenticity to white audiences as argued by Lomax while marginalizing their voices by signifying their position as second-class citizens as argued by Sterling Brown and black writers.23

However, dialect signaled not just race but a particular regional identity and place—being a “Southerner” residing in the southeast states of the contingent United States—that also risked subjugating the interviewees’ voices. Stereotypes abounded of the region as anti-modern, degenerate, and uneducated through works like Erskine Caldwell’s Tobacco Road. Intellectuals such as Rupert Vance and Howard Odum and government officials such as President Franklin Roosevelt alike were discussing how to handle the “Southern Problem.”24 The South’s economic woes, seen as exceptional and pervasive even by contemporary standards, combined with Jim Crow and spectacular racial violence, left questions about the region’s fitness for full inclusion and citizenship.25 Dialect became more broadly a marker that was one uneducated, rural, and southern.

Dialect became linked with southerness through the Southern Life Histories Project, which also used the “negro dialect” that flattened regional variations in black vernacular. FWP writers, almost all white, traveled across the South interviewing mostly white southerners. The project focused on southern workers at the lowest economic strata such as tenant farmers and mill workers. The aim, according to William T. Couch who led the effort, was to capture the conditions of the south in the words of the people. If Americans heard their voices, they would understand the social and economic challenges of the region and be more likely to see the larger causes of inequality, rather than blaming the conditions to individual moral failing, and support New Deal policies that aided the region. The FWP was at the center of defining Southern identity at a time when the meaning of the South was of great national interest.

Text analysis reveals that dialect was also prevalent in the Southern Life Histories Project. Like the Ex-Slave Narratives, words like “wuz” and “dere” were among the most prominent (Figure 5). However, dialect was not equally applied. It was used significantly more often for black interviews (Figure 6). Dialect then becomes a racial as well as southern marker and had the effect of positioning interviewees in the bottom socioeconomic and education strata of Southern society. What we then see is that that the Ex-Slave Narratives weren’t just about understanding slavery. They were a part of isolating slavery to a southern problem. Dialect became a rhetorical performance working powerfully at the intersection of race, class, and geography, producing a double subjugation that othered the formerly enslaved people represented in the Ex-Slave Narratives.

Explaining the collection in 1941, Botkin wrote, “These life histories, taken down as far as possible in the narrator’s words, constitute an invaluable body of unconscious evidence or indirect source material, which scholars and writers dealing with the South, especially, social psychologists and cultural anthropologists, cannot afford to reckon without.”26 The FWP then was at the center of defining Southern identity, not only at a time when the meaning of the South was of great national interest, but for future generations.

Bibliography

Andrews, William L. “An Introduction to the Slave Narratives.” Documenting the American South. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2004. https://www.docsouth.unc.edu/neh/intro.html.

Blei, David M. “Topic Modeling and Digital Humanities.” Journal of Digital Humanities 2, no. 1 (2012). http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/2-1/topic-modeling-and-digital-humanities-by-david-m-blei/.

Blight, David W. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2002.

Butler, Judith. Giving An Account of Oneself. New York: Fordham University Press, 2005.

Federal Writers’ Project Papers, 1936–1940, Southern Historical Collection. The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Administrative Files. 1936. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mesn001/.

Gardner, Sarah. Reviewing the South: The Literary Marketplace and the Southern Renaissance, 1920–1941. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Gordon, Avery F. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minneapolis-St. Paul: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Hale, Grace Elizabeth. Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940. New York: Pantheon Books, 1998.

Hill, Lynda M. “Ex-Slave Narratives: The Wpa Federal Writers’ Project Reappraised.” Oral History 26, no. 1 (1998): 64–72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40179473.

Hirsch, Jerrold. Portrait of America: A Cultural History of the Federal Writers’ Project. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2003.

Johnson, Walter. Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Meeks, Elijah and Scott B. Weingart. “The Digital Humanities Contribution to Topic Modeling.” Journal of Digital Humanities 2, no. 1 (2012). http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/2-1/dh-contribution-to-topic-modeling/.

Rapport, Leonard. “How Valid Are the Federal Writers’ Project Life Stories: An Iconoclast among the True Believers.” The Oral History Review 7 (1979): 6–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/ohr/7.1.6.

Soapes, Thomas. “The Federal Writers’ Project Slave Interviews: Useful Data or Misleading Source.” Oral History Review 2 (1977): 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/ohr/5.1.33.

Stewart, Catherine A. Long Past Slavery: Representing Race in the Federal Writers’ Project. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

Stewart, Kathleen. Space on the Side of the Road. Princeton: PrincetoncUniversity Press, 1996.

Stott, William. Documentary Expression and Thirties America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

Taussig, Michael. I Swear I Saw This: Drawings in Fieldwork Notebooks, Namely My Own. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Terrill, Tom E., and Jerrold Hirsch. “Replies to Leonard Rapport’s “How Valid Are the Federal Writers’ Project Life Stories: An Iconoclast among the True Believers”.” The Oral History Review 8 (1980): 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/ohr/8.1.81.

Yetman, Norman R. “Ex-Slave Interviews and the Historiography of Slavery.” American Quarterly 36, no. 2 (1984): 181–210. https://doi.org/10.2307/2712724.

Notes

The author would like to thank the CRDH editors Stephen Robertson and Lincoln A. Mullen, the two peer reviewers, attendees of the CRDH conference, and Suzanne Smith for the generous feedback. The article is also shaped by insights from a collaborative digital project with Courtney Rivard and Taylor Arnold called Voice of a Nation: Mapping Documentary Expression in New Deal America, which is forthcoming.

-

Hirsch, Portrait of America; Stewart, Long Past Slavery; Stott, Documentary Expression and Thirties America. ↩

-

Blight, Race and Reunion. ↩

-

Hirsch, Portrait of America. ↩

-

Stewart, Long Past Slavery, 93. ↩

-

The term “Ex-Slave” is problematic because it reduces the personhood of those in chattel slavery. Terms such as “enslaved people” have become prominent in order to assert that a person’s selfhood cannot be reduced to a “slave”. I have chosen to use the term “Ex-Slave Narratives”, which this set of writing has become known as, to signal a particular scholarly conversation and historiography that this paper engages with. ↩

-

The ex-slave collection includes documents from Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia. A small portion (approximately ten percent) of the collection were collected in states outside of the South. It is known that Virginia has a significant number of interviews but is not well represented because their materials were held by the state office. They are now at the Library of Virginia. See Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, vii. ↩

-

Stewart, Long Past Slavery. ↩

-

For an overview of the debate through the 1980s, see Yetman, “Ex-Slave Interviews.” ↩

-

The debate has extended to life histories more generally. See Rapport, “How Valid Are the Federal Writers’ Project Life Stories”; Terrill and Hirsch, “Replies to Leonard Rapport.” ↩

-

Hill, “Ex-Slave Narratives,” 64; Johnson, Soul by Soul, 226; Soapes, “The Federal Writers’ Project Slave Interviews,” 33–38. ↩

-

For examples, see Butler, Giving An Account of Oneself; Gordon, Ghostly Matters; Stewart, Space on the Side of the Road; and Taussig, I Swear I Saw This. ↩

-

Stewart, Long Past Slavery. ↩

-

Stewart, Long Past Slavery, 4. ↩

-

George Cronyn to Edwin Bjorkman, 2 April 1937, Box 24, Folder 1072, Federal Writers’ Project Papers, 1936–1940. ↩

-

Stewart, Long Past Slavery, 80; Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, v. ↩

-

Walter Cutter to Bernice Harris, 21 Dec 1938, Box 26, Folder 1108, Federal Writers’ Project Papers, 1936–1940; Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, xvii. ↩

-

Stewart, Long Past Slavery, 81. ↩

-

Stewart, Long Past Slavery, 197–228. ↩

-

Blei, “Topic Modeling and Digital Humanities”; Meeks and Weingart, “The Digital Humanities Contribution to Topic Modeling.” ↩

-

Gardner, Reviewing the South; Andrews, “An Introduction to the Slave Narratives.” ↩

-

George Cronyn to Edwin Bjorkman, 14 April 1937, Box 24, Folder 1072, Federal Writers’ Project Papers, 1936–1940. ↩

-

Stewart, Long Past Slavery, 85. ↩

-

Stewart, Long Past Slavery, 84–85. ↩

-

William Couch to Tarleton Collier, 14 Sept 1938, Box 24, Folder 1091, Federal Writers’ Project Papers, 1936–1940. ↩

-

Gardner, Reviewing the South; Hale, Making Whiteness. ↩

-

Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, viii–ix. ↩

Author

Lauren Tilton,

Department of Rhetoric & Communication Studies, University of Richmond, ltilton@richmond.edu,