Digitally Analyzing the Uneven Ground

Language Borrowing Among Indian Treaties

Abstract

“How smooth must be the language of the whites, when they can make right look like wrong, and wrong like right.” —Blackhawk

Word choice and the functioning of language itself has become an important subfield within indigenous history. As Patricia Limerick has noted, “the process of invasion, conquest, and colonization was the kind of activity that provoked a shiftiness in verbal behavior.”1 Blackhawk’s quote demonstrates that modern scholars were not the first individuals to recognize words as tools of settler colonialism. Recent scholarship has demonstrated how non-indigenous authors, politicians, and historians used language to exterminate Indians in the collective American consciousness even as they failed to do so in reality.2 Still, the written words that most impact the lives of Native Americans are contained within treaties. These documents have simultaneously provided justification for the exploitation of indigenous peoples while also providing a solid legal footing for the defense and exercise of indigenous rights. For Native Americans, these documents have influenced nearly every aspect of their lives in sometimes explicit but often unrecognized ways. The language and interpretation of these agreements concerns issues ranging from sovereignty and identity to school funding and fishing, hunting, and mineral rights.

Despite a growing literature focusing on these documents and the treaty making process itself, the nearly four hundred different treaties have yet to be analyzed using the methods of digital history.3 The small size of the corpus does limit the ability to yield insightful results from common digital approaches such as topic modeling or word embedded modeling, but this does not mean digital methods have nothing to offer. This essay examines the treaties using a more applicable digital approach: text reuse. I argue that treaty authors frequently borrowed both content and language from previous documents but only rarely did this borrowing occur over long periods of time or across geographic regions. Most treaties borrowed from their immediate temporal predecessors and geographic neighbors. While borrowing was common, many treaties did not include any borrowed language. This absence of borrowing raises questions concerning indigenous agency and the supposed efficiency and strength of the growing bureaucratic American state. These patterns illustrate the inconsistency of federal Indian policy. After examining these language borrowing trends, this essay concludes with two case studies that demonstrate how digitally detecting text reuse can complicate our understanding of the treaty making process.

1. Research questions and methodology

This research project was framed around several specific questions:

-

To what extent did treaties adhere to a standard structure or form?

-

Were there specific treaties that subsequent authors and negotiators modeled their agreements after in terms of language?

-

If borrowing did occur, what portions of previous treaties did authors or negotiators borrow and why?

-

How did time and geography influence the content and language of treaties?

Central to answering these questions is the method of digitally detecting text reuse or borrowing.4 After breaking the treaties apart at the paragraph level, I computed the similarity scores of the documents and turned the results into the visualizations that appear in this essay.5 This process helped detect groups of texts that borrowed from the same “exemplar” document. In order to add a geographic dimension, I geolocated the treaties by both the location where the treaties were negotiated and the general location of the regions affected by the treaties.

2. A macro view of the uneven ground

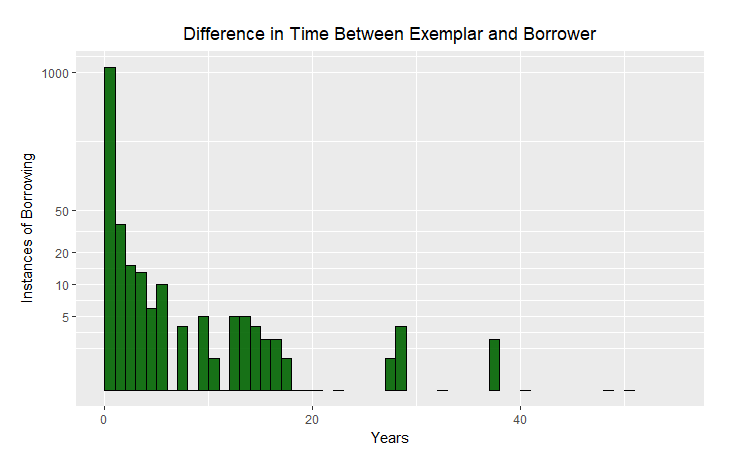

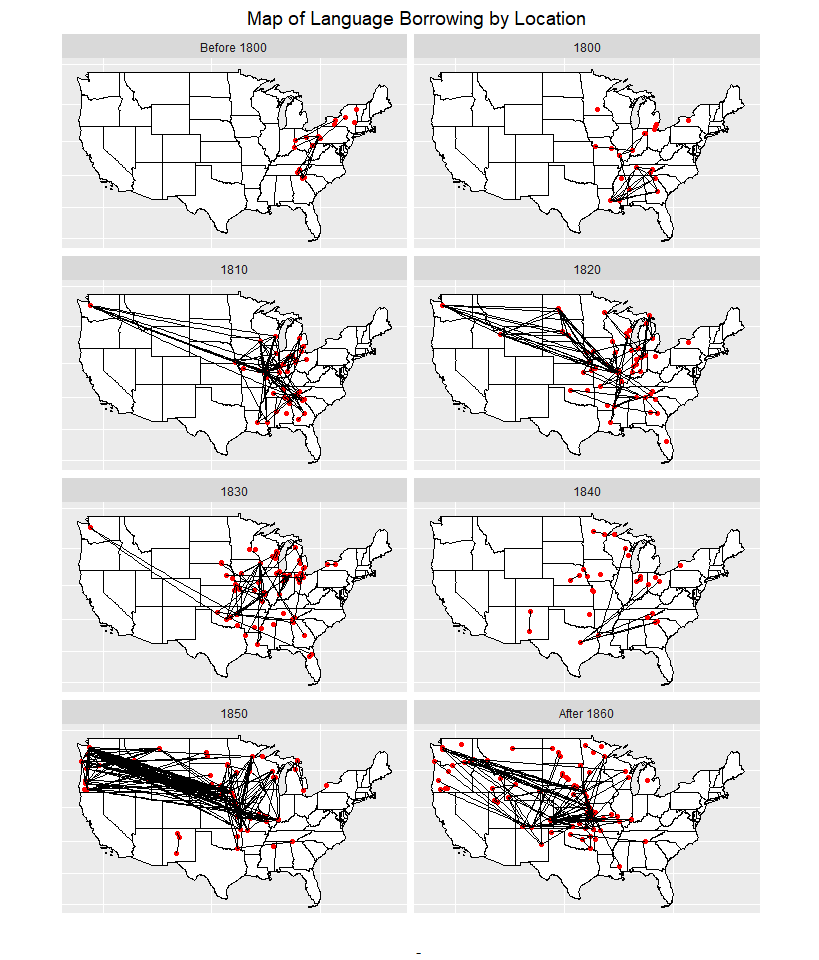

Analyzing the language borrowing from a macro perspective reveals that negotiators relied heavily upon previous agreements to shape subsequent documents. While the practice of borrowing was widespread, only rarely did this borrowing occur over long periods of time or across geographic regions due to the inconsistency of federal Indian policy. In most cases, treaties only borrowed from their immediate temporal predecessors and geographic neighbors. As the histogram in figure 1 shows, the vast majority (89%) of the treaty borrowing occurred within a two year span.6

The lack of long-term borrowing highlights a general characteristic of Indian treaties, contextual composition. As David Watkins and K. Tsianina Lomawaima have noted, federal Indian policy is an “uneven ground” characterized by “inconstancy, indeterminacy, and variability.” They observed that “Indian policy has not proceeded along some smooth racetrack, but has pitched and bumped over the rutted tracks that the conflicting interests of tribes, states, federal agencies, railroads, energy and industrial barons, homesteaders, tourists, and casual visitors have carved across Indian Country.”7 These competing interests resulted in a pattern of language borrowing that was geographically and temporally limited. Without a governmentally mandated master document detailing the structure, content, and language of a treaty, the commissioners molded treaties to correspond to unique situational circumstances. In doing so, they often borrowed text and content from previous documents.

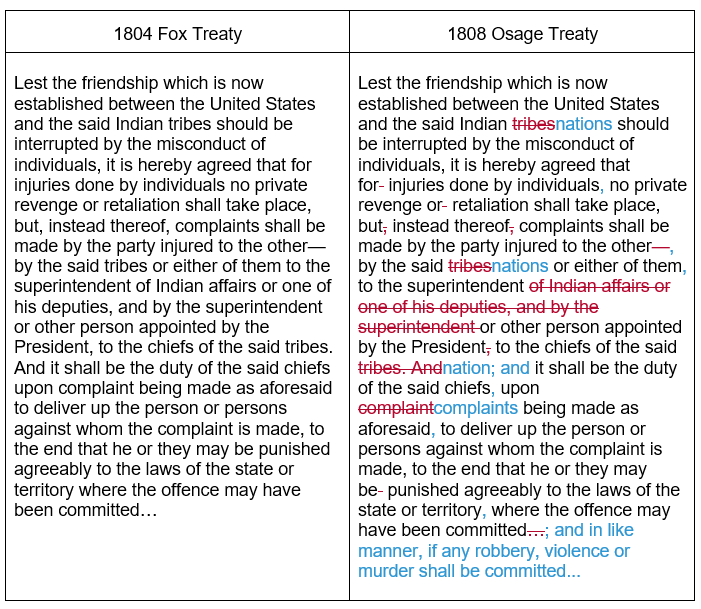

The benefit of using digital methods to detect text reuse is that it can identify language pattern similarities that would be difficult (and time consuming) to detect using close reading (figure 2). Thus, it is possible to see what early 19th century treaty a negotiator used as a template in the 1850s.

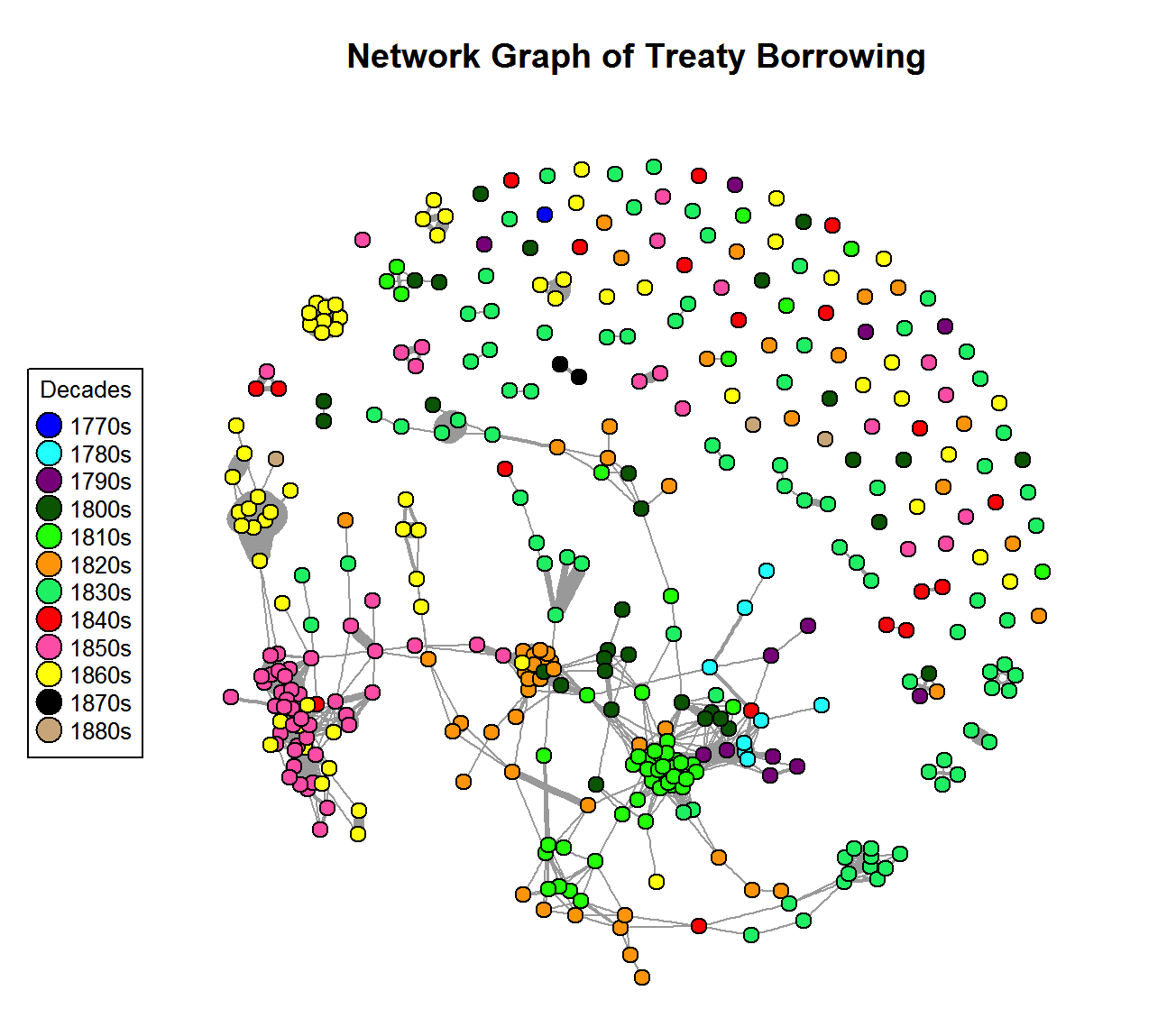

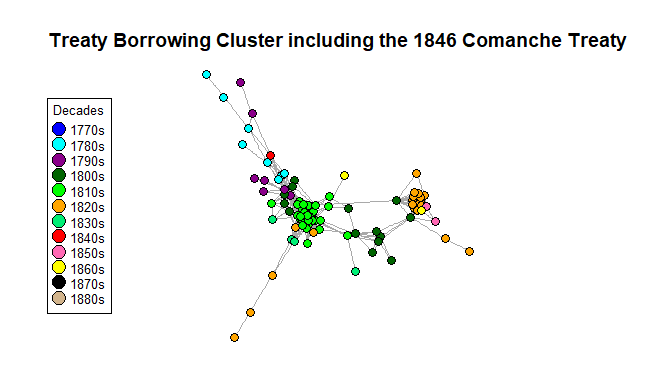

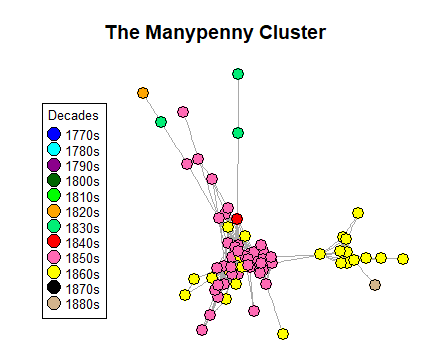

As the network graph in figure 3 indicates, there was very limited borrowing across time. Most of these clusters of treaties contain only one or two colors (corresponding to decades). The graph also captures, in the form of clusters, the practice of treaty borrowing where a commissioner composed several treaties within a short span of time.

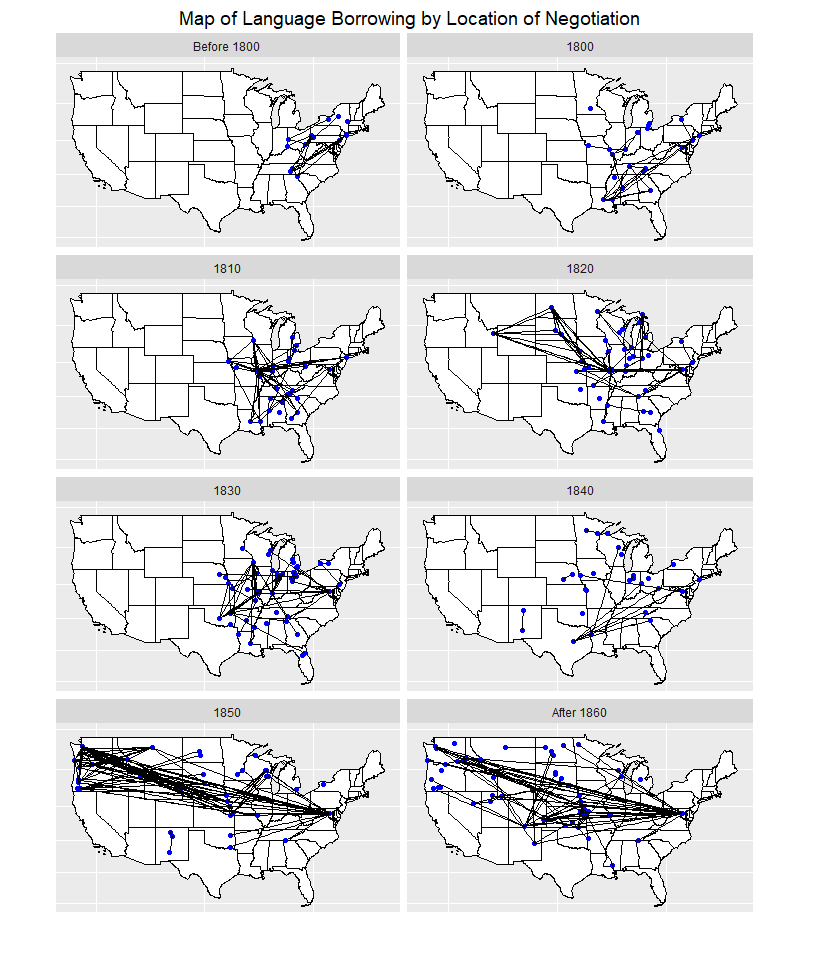

Commissioners rarely veered from their groove in the uneven ground and thus limited borrowing geographically and temporally. Breaking apart the borrowing patterns by decade reinforces this observation (see figures 4 and 5). There are only a few examples of treaties that borrowed language from agreements in different geographical regions.

3. A micro view of the 1846 Comanche Treaty

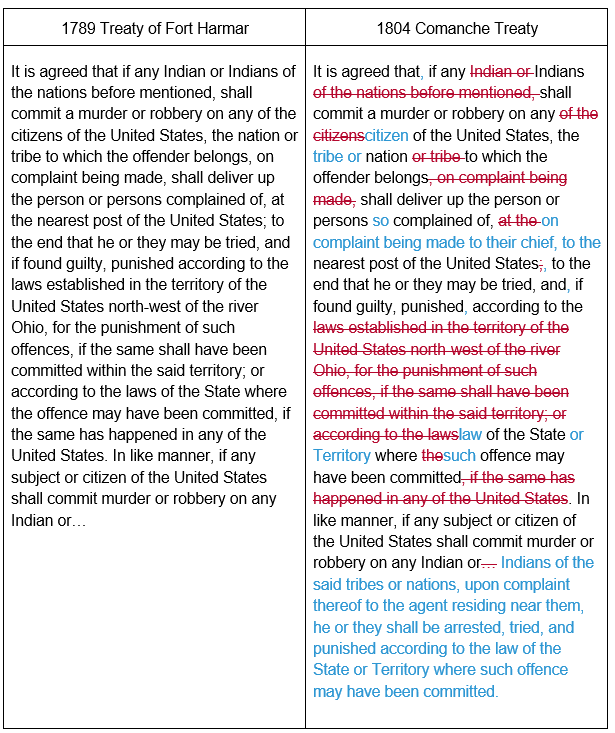

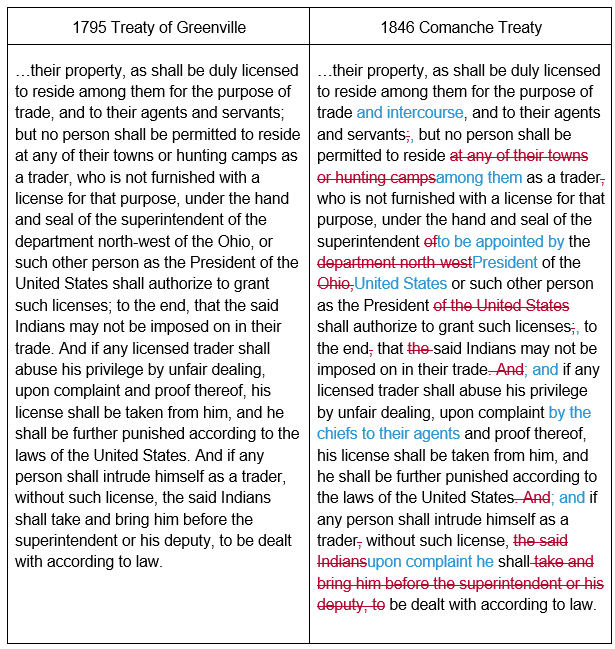

While the general trend for language borrowing among treaties was limited by time and geography, there were some exceptions to this rule. The most obvious example is the 1846 treaty signed by the Comanche. Unlike most treaties, the negotiators/authors of this treaty looked to the distant past for inspiration. As the excerpts in figure 6 show, the 1846 Comanche treaty obviously borrowed language from the Fort Harmar treaty written fifty-seven years before.

The Comanche treaty also borrowed language from the 1790 treaty with the Creek, and the 1795 Treaty of Greenville. The network graph in figure 7 shows the sub-group of treaty borrowing containing the 1846 treaty (the only red dot or treaty from the 1840s).

There are two plausible explanations for the long-term language borrowing of the 1846 Comanche treaty. The first possibility is that the language borrowing can be attributed to the background of the commissioners, Pierce Mason Butler and M. G. Lewis. Butler was a former governor of South Carolina (1836–1838) who became an Indian agent, a post which he held until his death during the Mexican American War. Butler’s father, William, was a politician who also served in numerous military campaigns against Indians during a thirty-nine year military career (1775–1814). It is possible that the younger Butler looked to his father’s career for guidance while serving as an Indian agent.

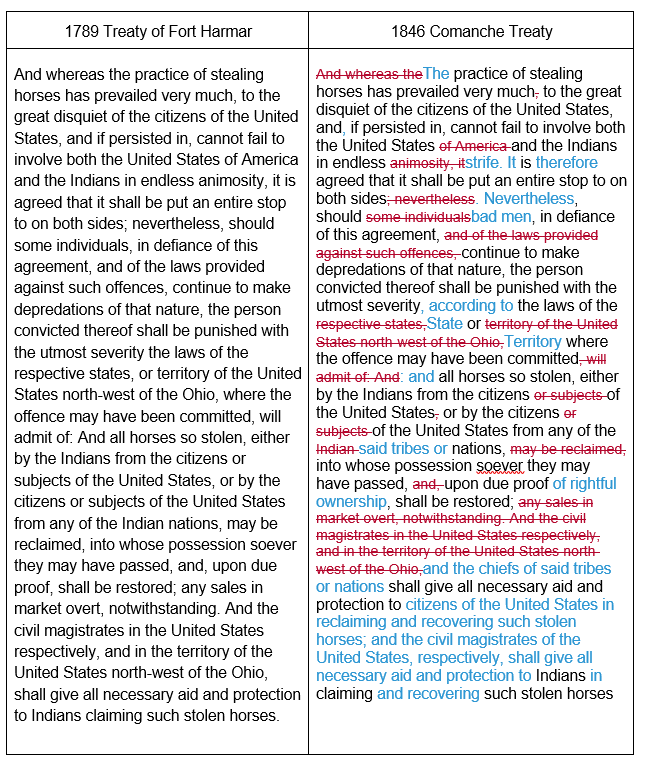

A more likely explanation is that Butler and Lewis looked to the past because of the specific historical milieu of Comancheria in the 1840s. The economic engine of the powerful Comanche empire was a system of raiding and trading. The Comanche raided encroaching American and Mexican settlements and then sold their acquisitions to other Indian nations or non-indigenous traders. As Pekka Hamalainen has argued, “Texas spent three-quarters of a century as a carefully managed livestock repository for Comancheria.”8 While the Comanche had a different objective, their system of intensive raiding shared many similarities with the coalition of Ohio Indian nations who raided frontier settlements to stop American encroachment in the 1780s and 1790s.

It appears that Butler and Lewis saw enough parallels between these two situations that they borrowed language from the Ohio treaties nearly verbatim (see figure 8).9 Despite this recycling of words, the borrowed passage was surprisingly appropriate for the situation in Comancheria.

The two situations were also similar in that the American government needed to suppress violence on its ever expanding frontier without a substantial and stable population of settlers. Butler and Lewis once again looked to an 18th century treaty to address a contemporary problem by adopting a licensing system (see figure 9).

The example of the Comanche treaty demonstrates how detecting text reuse can complicate our understanding of historical power dynamics. However, just as language borrowing raises and answers interesting questions, so does its absence.

4. A micro view of the Ojibwe Treaties

How do we make sense of the large number of treaties that did not borrow language from previous documents and did not become exemplars for subsequent agreements? For instance, the 1854 Chippewa Treaty does not share any borrowed paragraphs; meanwhile, the 1855 Chippewa Treaty shares several paragraphs. Nothing in the text of the 1854 Chippewa Treaty suggests that it is a unique document. It contains the expected themes and form of any other treaty. The network graph in Figure 10 indicates a different story as the treaty appears as an isolated node without any connections to other treaties. So why did this document not borrow from other texts? Part of the answer may lie in the individuals who negotiated the treaty.

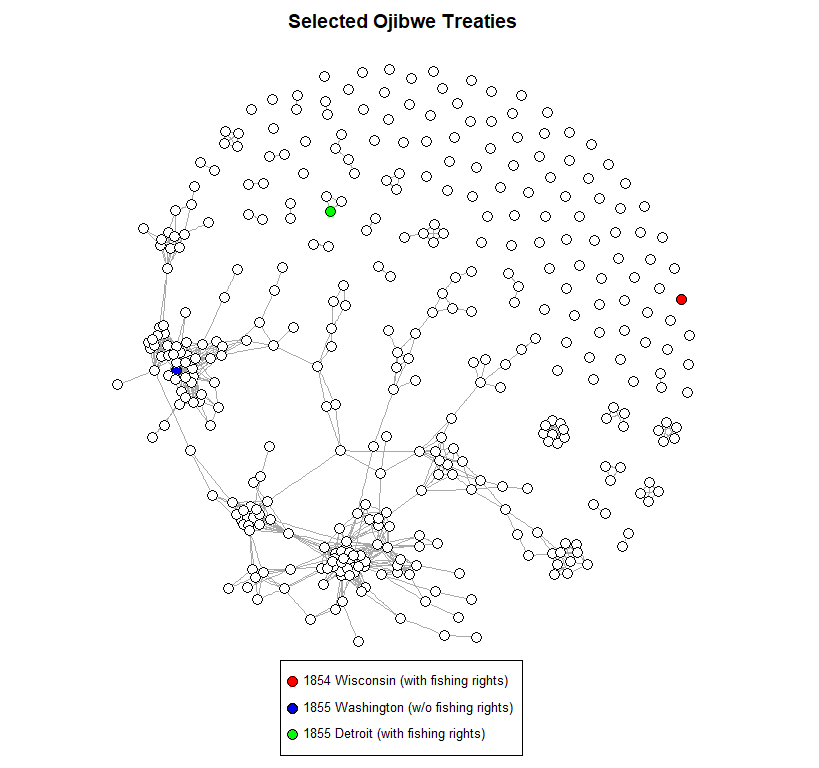

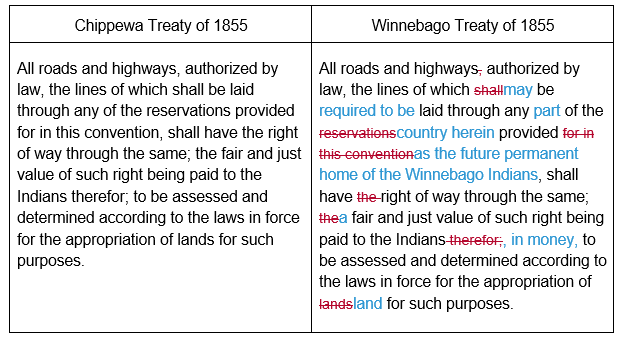

As Francis Paul Prucha has noted, when problems arose in the treaty making process, “pragmatic decisions held sway, with a good deal of discretion left in the hands of the treaty commissioners.”10 In trying to understand the language of any particular treaty, it is necessary to examine the personalities and experience of the commissioners and Indian negotiators. Henry C. Gilbert and David B. Herriman negotiated the 1854 Chippewa Treaty; but, unlike many other commissioners, they only negotiated a small number of treaties. In contrast, the commissioner of the 1855 Chippewa Treaty, George Manypenny, was the signatory on over fifty different treaties. Not surprisingly, the borrowed or shared paragraphs of the 1855 Chippewa Treaty can be traced back to Manypenny’s other negotiations (see figure 11).

Manypenny had the job of organizing territories on the central plains in order to provide land for white settlement and the construction of railroads.11 As the text from the excerpts in Figure 12 demonstrates, these treaties were designed to obtain a solid legal footing for future American encroachment. With a federally directed goal in mind, Manypenny crafted nine treaties signed with different nations in Washington D.C. in 1854. For whatever reason, the Ojibwe were not included in Manypenny’s first wave of treaties. However, they were included in a second wave of treaties signed in Washington D.C. in the spring of 1855. Thus, much of the borrowed or shared language of the 1855 treaty can be explained by Manypenny’s attempt to force federal policy upon a myriad of different Indian nations. In a strange twist, Gilbert and Manypenny then teamed up to craft two other agreements with the Ojibwe and Ottawa nations of Michigan in the fall of 1855 in Detroit.

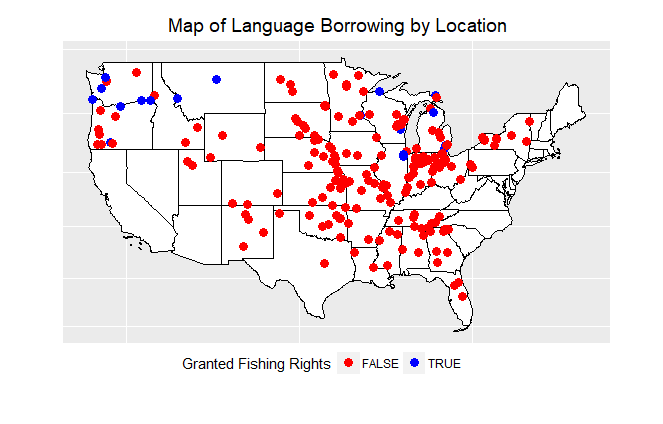

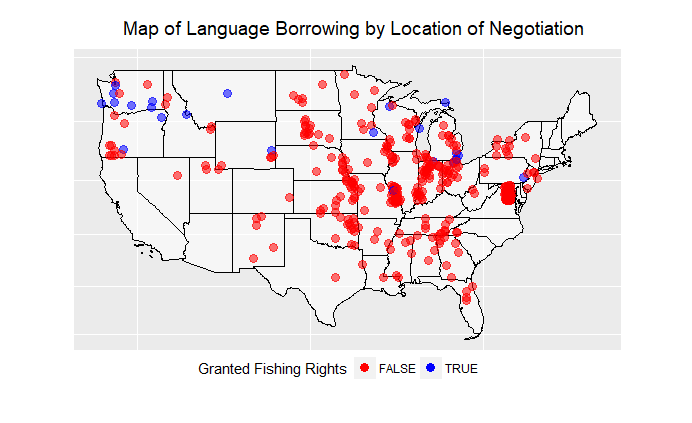

Better understanding the construction of these documents is extremely important for the modern Ojibwe people who have a large stake in the language of these documents as they depend upon them to protect their fishing and hunting rights. For example, the 1854 Chippewa Treaty negotiated by Gilbert and Herriman included a provision protecting “the right to hunt and fish” on specified lands. This provision is absent from the 1855 Chippewa Treaty negotiated by Manypenny in Washington; but, it reappears in the 1855 Ottawa and Chippewa Treaty negotiated by Manypenny and Gilbert in Michigan. Why were fishing rights included in some agreements and not others?.

It is interesting that the guarantees of fishing rights only occurred in treaties where Gilbert was one of the commissioners. Can the inclusion or absence of fishing rights be attributed to Gilbert’s presence? Or, is the inclusion of fishing rights connected to the physical location in which the treaties were negotiated and signed? Both treaties that included fishing rights were negotiated in Wisconsin and Michigan respectively. The treaty negotiated in Washington failed to address fishing rights. Did the location of negotiation affect the amount of agency that indigenous negotiators could exert?

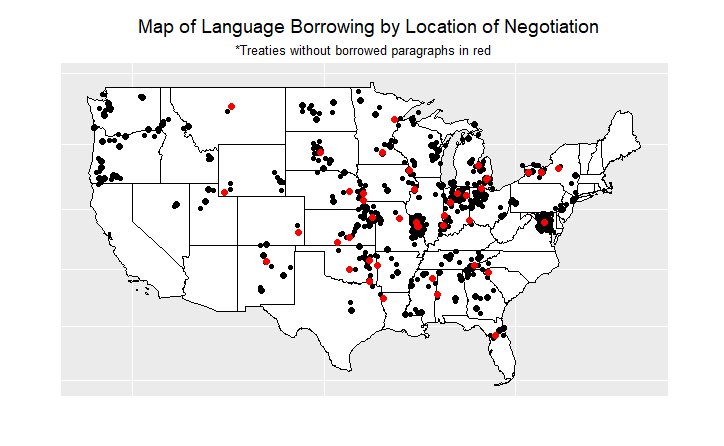

In order to test the possibility of indigenous agency accounting for the unconnected treaties, I examined whether or not the treaties granted fishing rights based upon the location of negotiation. In theory, the treaties that contained clauses protecting fishing rights would suggest a significant amount of indigenous agency or negotiating skill (figures 13, 14, and 15).

It appears that there is some connection between the location of negotiation and the inclusion of fishing rights given the absence of blue dots near negotiating hubs; but, the evidence is not conclusive. Still, this opens an avenue for further inquiry, especially if the trend holds true for hunting, gathering, and other rights as well. As Colin Calloway has observed, “treaties are a barometer of Indian-white relations in North America” and language borrowing patterns provide another means of measuring that pressure.12

Conclusion

Examining the nearly four hundred Indian treaties using digital methods revealed a network of language borrowing. While the practice of borrowing was widespread, it was confined geographically and temporally due to the inconsistency of federal Indian policy. In certain cases such as the 1846 Comanche Treaty, borrowing across decades and geographic regions did take place in order to address similar contemporary issues. While highlighting the presence of borrowing, further investigation is needed to understand why it occurred. The example of the language borrowing patterns of the Ojibwe treaties suggest that the particular situational dynamics in which treaties were negotiated and/or signed had an impact on the content and language of the agreements. This study demonstrates how digital methods can be used to gain new insight from well-known sources. By demonstrating the benefits of digitally detected text reuse using Indian treaties, this study opens the door to this method’s further use on different corpora.

Bibliography

Buss, James. Winning the West with Words: Language and Conquest in the Lower Great Lakes. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011.

Calloway, Colin G. Pen and Ink Witchcraft: Treaties and Treaty Making in American Indian History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Cordell, Ryan. “Reprinting, Circulation, and the Network Author in Antebellum Newspapers.” American Literary History 27, no. 3 (September 1, 2015): 417–45.

Cronon, William, and George A. Miles. Under an Open Sky: Rethinking America’s Western Past. W. W. Norton & Company, 1993.

Funk, Kellen, and Lincoln A. Mullen. “The Spine of American Law: Digital Text Analysis and U.S. Legal Practice.” American Historical Review 123, no. 1 (2018): 132–64.

Hamalainen, Pekka. The Comanche Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

O’Brien, Jean M. Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Prucha, Francis Paul. American Indian Treaties: The History of a Political Anomaly. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Vine, Deloria, Jr., and David E. Wilkins. Tribes, Treaties, and Constitutional Tribulations. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999.

Wilkins, David E., and K. Tsianina Lomawaima. Uneven Ground: American Indian Sovereignty and Federal Law. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001.

Notes

-

Limerick, Under an Open Sky, 83. ↩

-

See for example: Buss, Winning the West with Words; O’Brien, Firsting and Lasting. ↩

-

See for example: Vine and Wilkins, Tribes, Treaties, and Constitutional Tribulations; Wilkins and Lomawaima, Uneven Ground. ↩

-

This is not the first study to employ such an approach. Ryan Cordell successfully used this method to trace the reprinting and circulation of articles by a network of 19th century newspapers. Kellen Funk and Lincoln Mullen also used this approach to trace the state to state borrowing of legal code within American law. See Cordell, “Reprinting, Circulation, and the Network Author in Antebellum Newspapers”; Funk and Mullen, “The Spine of American Law.” ↩

-

After scraping the text of the documents from Oklahoma State’s Kappler Project website, the treaties were broken apart at the paragraph level in order to compute similarity scores that went beyond a treaty to treaty comparison. Using Lincoln Mullen’s “textreuse: Detect Text Reuse and Document Similarity” package for R, I computed the similarity of the documents and turned the results into the visualizations that appear in this essay. See Lincoln Mullen, “textreuse: Detect Text Reuse and Document Similarity,” R package version 0.1.2 (2015): https://github.com/ropensci/textreuse. ↩

-

This number is slightly skewed due to the fact that commissioners often composed, within a few days or months, a cluster of treaties dealing with a group of nations or bands. The text reuse detection model still includes these treaties as examples of borrowing. ↩

-

Wilkins and Lomawaima, Uneven Ground, 6. ↩

-

Hamalainen, The Comanche Empire, 245. ↩

-

This assumption may be impossible to prove without a written statement from the commissioners, but it is telling that the paragraphs that they chose to borrow contained language concerning raiding. ↩

-

Prucha, American Indian Treaties, 208. ↩

-

Prucha, 243. ↩

-

Calloway, Pen and Ink Witchcraft, 3. ↩

Appendices

Author

Joshua Catalano,

Department of History and Art History, George Mason University, jcatala3@gmu.edu,