Mining the ICC

Macroanalysis of the Indian Claims Commission

Abstract

From 1946 until 1978, the Indian Claims commission (ICC) deliberated over the wrongs done to Indian Country by the United States government and awarded over $600 million dollars.1 The ICC inscribed into its legal decisions changing relationships at a crucial period in Federal-Indian relations. The Commission began during the Termination Era, a particularly low period of tribal autonomy. Conservative Congressional members and President Harry Truman believed the Federal government would save funds by “terminating” its trust relationship with tribes.2 These politicians did not anticipate that the Indian claims cases were so complex and contentious that the Commission had no hope of finishing in the initially allotted five years. By the end of the Commission’s lifespan in the 1970s, the Federal Government’s policy of termination had flipped 180 degrees. With the failure of Termination and protest by the American Indian Movement, the government now sought to treat tribes as independent nations during what Francis Paul Prucha noted was a period of increased tribal self-determination and activism.3

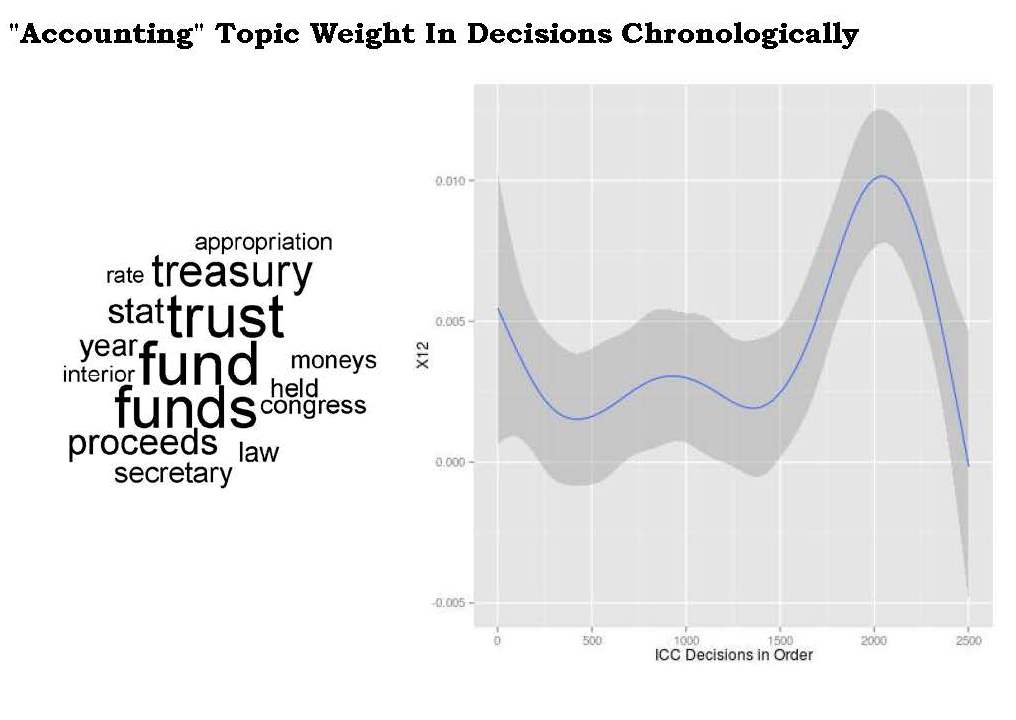

By analyzing the discourse of the decisions, I hope to move beyond their legalese to see how and in what ways the decisions both codified the process of changing Federal-Indian relations, and achieved a measure of political reconciliation for indigenous peoples.4 In parsing a complex legal corpus containing the decisions of the ICC, topic modeling showed which documents deserved a closer look among the thousands of legal decisions. The decisions themselves are also results of a legal process and events at the time affected their discourse. Based on my topic model analysis, I saw a spike in what seemed like counterintuitive, deeply technical accounting decisions supporting the tribe’s legal positions in the early 1970s. Other historians have written extensively on indigenous activism at this time, including the occupations of Alcatraz, Wounded Knee, and the BIA headquarters. Analysis of these decisions and additional study of their context portrayed the ICC not as a variance, but a fundamental element of political reconciliation for indigenous peoples.

Ernesto Verdeja recently presented three central elements of political reconciliation in postcolonial societies: (1) a critical reflection on the events that occurred; (2) symbolic or material recognition of the harms; (3) increased political participation.5 The long ICC process helped produce these elements of reconciliation or mutual respect. Previous scholars have rightly focused on the flaws of a process partly designed by politicians desiring “Termination” of the trust relationship. David Wilkins correctly lists the many ways in which it was rigged at its outset: 1) limiting claims only to tribes and not individuals; 2) Ignoring non-recognized tribes, particularly in the eastern US because they did not meet white conceptions of “Indian-ness”; and 3) functioning as a court rather than a fact-finding body, including adversarial proceedings and limited types of admissible evidence.6 Charles Wilkinson also recounts how the return of money instead of land had a negative effect on tribes.7 Despite these hindrances, the ICC brought several forms of symbolic reconciliation to tribal nations and increased tribal sovereignty. By using text mining as an exploratory and analytical tool, I aligned particular cases on monetary accounting with increased tribal activism. These processes both changed the decisions’ discourse, and also furthered political reconciliation and tribal sovereignty.

Text mining can illuminate traditional documentary evidence in colonial archives. The National Archives and Records Repository (NARA)—one of the world’s largest colonial archives—has recently released a draft strategic plan which calls for 500 million pages to be digitized by 2024.8 Keyword and chronological search methods can achieve only so much in the enormous digital archive. Digital analytical methods, such as topic modeling and text mining, highlight unique discourses in the documents (though real insight is never simply spat out via the right combination of code).

To analyze the decisions, I first scraped them from Oklahoma State’s website and extracted text from the PDFs text using Google’s free Tesseract optical character recognition (OCR) software. I generated “topics” or groups of words that were statistically more likely to be found together in the ICC decisions.9 These “topics” can be analyzed to loosely determine what discourses certain decisions, or groups of decisions, likely contain.10

Topic modeling requires much trial and error in creating an optimal number of topics, 100 in this case, and stoplists, which are the words ignored by the program. I used a traditional English stoplist, plus tribal and geographical names, like “pueblo” or “Alaska.” These were not relevant to my research questions. Literary practitioners of distant reading, like Matthew Jockers, call this the “character problem.”11 With “characters” removed, the topics or discourses at the cases’ heart remained.

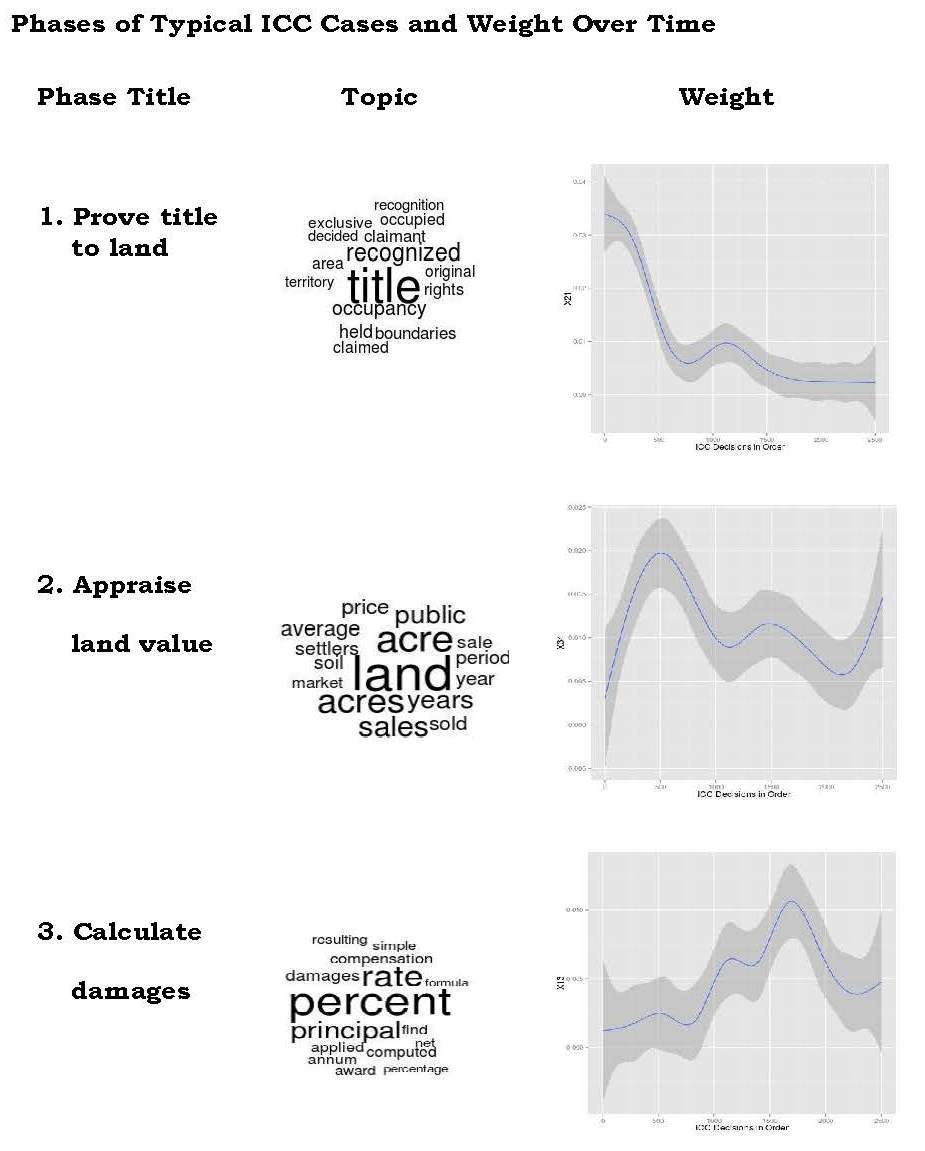

In closely reading thousands of legal decisions, the sheer size can swallow subtle and confrontational uses of language at times while reading distantly can highlight these destabilizing narratives (like the accounting topic described below). The topics can also display common historical features well described in the literature.12 In the first phase of a typical ICC case, the tribe would have to prove title to their land. This involved historians and anthropologists conducting extensive research and writing monograph-length expert witness reports over a number of years. Second, the government and tribes would determine valuation and liability for the land, often with help from historians, accountants, and other experts. Finally, the Commission multiplied damages by interest rates over time. Three topics matched this typical ICC claims process:

As central components of many ICC cases, these topics are expected. This familiarity may confirm that our number of topics approach an optimal number for analysis. The topics are shorthand for the discourse in the decisions, which match what we expect based on the literature.

Notably in figure one, the Phase three topic peaked between decision 1500 and 2000, approximately in the late 1960s. After this time, the Commission’s typical case involved settlement with tribes whose expert witnesses had completed detailed reports.13 This momentum presaged major changes for the Commission and Federal-Indian relations in the 1970s. The change in approach also coincided with an ICC leadership change. On May 2, 1969, President Nixon appointed Brantley Blue, a member of the Lumbee Tribe. Blue was the first indigenous Commissioner and provided an emphatic voice behind the scenes of the ICC. His impact is no surprise when discourse and legal justifications changed in the 1970s.14

In 1970, President Nixon announced his self-determination doctrine for tribes.15 This announcement officially ended the Termination Era and returned Federal-Indian policy towards sovereignty and a nation-to-nation relationship. On November 2, 1972 members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) forcefully took over the BIA building in Washington, DC. This occurred days before the 1972 Presidential election, a politically charged period.16 On February 27, 1973, AIM entered another significant space on the Pine Ridge Reservation, Wounded Knee, which they held for 71 days. This occupation was significantly more violent with two tribal members killed and a federal agent shot.17 Five months after the end of the occupation of Wounded Knee, members of the Indian Claims Commission decided Docket 279-C and 250-A. These dockets initially awarded no money to the Blackfeet Tribe but required the government to perform an accounting of the tribes’ monies. This 85-page decision listed the exact ways in which the United States would conduct an accounting of the tribe’s money.18

The highly technical acts of the Indian Claims Commission contrast with the violence and rhetoric used by members of AIM. One operated wholly within “civil” white society, the other operated in opposition to the colonial rule of law.

The accountings and claims also provided a measure of symbolic and monetary victory for tribal members. The Muskogee (Creek) Nation won $4 million from an ICC Judgement, but due to its large population, each Muskogee member only received $111.13. Despite the relatively small amount of money, one tribal member commented: “I’ll always say it was that Indian Money that freed us from bondage…because so many of those who had been so down on the Indians had to face up to us over that money.”19 It is not peculiar then that accounting cases spiked at a time when Indian Country was both at its most volatile in over 50 years and with input from its first indigenous Commissioner. While Native Americans were taking back their land by force, the ICC focused on its most technical cases concerning money and accounting claims. Yet these technical accounting claims had force both for individual Indians and tribes. With the “trust” relationship between the Federal government and indigenous peoples based on centuries of treaties, accounting for the tribes monies, lands, and resources symbolically restored the perpetually unbalanced relationship.

Verdeja’s theory of political reconciliation in postcolonial settler societies aligns well with the ICC claims process highlighted by topic modeling and traditional scholarship on the ICC.20 First, a critical reflection on the events occurred. In the case of the Indian Claims Commission, extensive histories by anthropologists and historians acting as expert witnesses provided broad and at times critical views of colonial violence. It is no coincidence that the journal Ethnohistory was founded in 1954 during intensive research by these ICC expert witnesses.21 This broad ethnohistorical data was extremely valuable to tribes making sense of the colonial-settler violence. Second there was symbolic or material recognition. The roughly $600 million dollars in awards doled out by the Commission were far more symbolic than material. More than the actual monies generated by the ICC for tribal members, which were but a fraction of the values of lands and resources originally stolen, the process of going through the “accounting” reflected some justice for tribal members. Appointment to the ICC of Commissioner Brantley Blue finally brought indigenous participation to the proceedings and allowed for changes in the Commission’s perspective. Verdeja’s third core element of the reconciliation process was political participation. In 1975, following the Wounded Knee occupation and the Blackfeet accounting decision, Congress passed the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act. While the path was not smooth, the act encouraged what it called “maximum Indian participation.”22 In the decades since, tribes have incrementally increased management of their own government as well as added to their landbase.23 The ICC and its findings have formed a crucial, though quiet backbone to some of Indian Country’s successes over the latter half of the Twentieth Century.

Scholars and Indigenous activists will continue to argue how much justice the ICC brought to Indian Country. Yet these efforts undoubtedly increased tribal sovereignty and self-determination. By replacing the BIA administration with tribal governance and renewing their traditional political cultures, tribes are slowly starting to see the economic gains and even increases in tribal land base denied to them during the symbolic ICC victories. Work remains to unpack the connections between AIM's occupations and the ICC’s accounting efforts, but it was the distant view of these colonial decisions that enabled me to make connections to crucial indigenous events of the 1970s. Discourses in the ICC decisions signaled major changes in the Federal-Indian relationship and began the continuing process of political reconciliation.

Bibliography

Blackfeet, et. al. v. US and Fort Belknap v. US; Dkt 279-C, Dkt 250-A, Opinion, 6/7/1974, 34 Ind. Cl. Comm. 122. https://cdm17279.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/api/collection/p17279coll10/id/2572/download.

Bushyhead, Yvonne. “In the Spirit of Crazy Horse: Leonard Peltier and the AIM Uprising.” In The Winds of Injustice: American Indians and the U.S. Government, edited by Laurence Armand French, 77–112. New York: Garland Publishing, 1994.

Jockers, Matthew. “Secret Recipe for Topic Modeling Themes.” April 12, 2013. http://www.matthewjockers.net/2013/04/12/secret-recipe-for-topic-modeling-themes/.

Kuykendall, Jerome T. Final Report of the Indian Claims Commission. September 30, 1978. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1979.

Lee, Robert. “Accounting for Conquest: The Price of the Louisiana Purchase of Indian Country.” Journal of American History 103, no. 4 (March 2017): 921–944. https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jaw504.

McCallum, Andrew Kachites. “MALLET: A Machine Learning for Language Toolkit.” 2002. http://mallet.cs.umass.edu/.

National Archives and Records Administration. “Draft National Archives Strategic Plan.” August 21, 2017. https://www.archives.gov/about/plans-reports/strategic-plan/draft-strategic-plan.

Peters, Gerhard and John T. Woolley, eds. The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/index.php.

Perdue, Theda. “Presidential Address: The Legacy of Indian Removal.” Journal of Southern History 78, no. 1 (February 2012): 3–36.

Prucha, Francis Paul. The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986.

Rosenthal, Harvey. “Their Day in Court: A History of the Indian Claims Commission.” PhD diss., Kent State University, 1976.

Verdeja, Ernesto. “Political Reconciliation in Postcolonial Settler Societies.” International Political Science Review 38, no. 2 (March 2017): 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512115624517.

Wilkins, David E. Hollow Justice: A History of Indigenous Claims in the United States. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013. https://doi.org/10.12987/yale/9780300119268.001.0001.

Wilkinson, Charles F. Blood Struggle: The Rise of Modern Indian Nations. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2005.

Notes

-

Rosenthal, “Their Day In Court.” Rosenthal has also published a now out-of-print monograph by Garland Press. ↩

-

Wilkins, Hollow Justice, 50–52, 68. ↩

-

Prucha, The Great Father, 385. ↩

-

For other recent work using the ICC decisions in novel, digitally driven research, see Lee, “Accounting for Conquest.” ↩

-

Verdeja, “Political Reconciliation,” 227–241. ↩

-

Wilkins, Hollow Justice, 76–80. ↩

-

Wilkinson, Blood Struggle, 223–231. ↩

-

National Archives and Records Administration, “Draft National Archives Strategic Plan.” ↩

-

I generated topics using a variety of R packages, especially MALLET. For more detail on methodology, all code is on my github page: http://www.github.com/petercarrjones/icc-data. ↩

-

Jockers, “Secret Recipe for Topic Modeling Themes. ↩

-

Rosenthal, Their Day in Court, 161–164. ↩

-

Kuykendall, Final Report, 15–16. The “settlement” and “expert” topics behaved similarly in the analysis. ↩

-

Kuykendall, Final Report, 17; Wilkins, Hollow Justice, 86. ↩

-

Richard Nixon, “Special Message to the Congress on Indian Affairs,” July 8, 1970, The American Presidency Project, eds. Peters and Woolley, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=2573. ↩

-

Bushyhead, “In the Spirit of Crazy Horse,” 81–82. ↩

-

Bushyhead, “In the Spirit of Crazy Horse,” 82–84. ↩

-

Blackfeet, et. al. v. US and Fort Belknap v. US; Dkt 279-C, Dkt 250-A, Opinion, 6/7/1974, 34 Ind. Cl. Comm. 122, https://cdm17279.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/api/collection/p17279coll10/id/2572/download. ↩

-

Perdue, “Presidential Address,” 32. ↩

-

Verdeja, “Political Reconciliation,” 227–241. ↩

-

Wilkins, Hollow Justice, 124–125. ↩

-

Prucha, The Great Father, 379–380. ↩

-

Wilkinson, Blood Struggle, 206–207. ↩

Appendix

Author

Peter Carr Jones,

Department of History and Art History, George Mason University, pjones15@masonlive.gmu.edu,