Geo-Locating Census Micro-Data

Segregation, Clustering, and Residential Behaviours of Migrant Communities in London, 1881–1911

Abstract

I. Introduction

“We must look to the census as our basic source,” stated Lloyd Gartner, “and almost entirely abandon attempts to derive annual immigration figures from other sources.”1 Gartner’s 1960 emphasis on the census as the fundamental source for studying migration and migrants remains a salient point. Despite the digitisation of new sources concerning immigration into Britain, including Naturalisation Reports, the census remains the most extensive socio-economic dataset for the subject.

Most studies of population mobility and Britain are in reference to those who emigrated, rather than those who arrived. However, with an extensive Empire, the United Kingdom served as the crossroads of the world, with individuals and communities arriving throughout the long nineteenth century. Between 1881 and 1911, hundreds of thousands of foreign-born migrants entered, passed through, and settled into England and Wales. Including the Irish, almost a million foreign-born migrants were residing in England and Wales by 1911, with a much larger second-generation progeny.

Scholars have long noted the spaces of exception where large, distinctive migrant communities formed.2 However, studies have typically relied on registration district geographies as the spatial unit of investigation. The aggregation of populations at this level results in distortions and betrays the complex behaviours occurring at a neighbourhood and street level.3 Current research is attempting to redress this reliance upon amassed population statistics. Through two case studies of Victorian and Edwardian London, this article argues that the individualised geo-locating of households as enumerated in the census is of far higher value when measuring segregation amongst migrant communities. Further, this article demonstrates that with time, migrants were intrinsically mobile and areas of settlement underwent profound transformations.

II.

To explore the segregating behaviours of migrants at an individual household level, two examples are drawn from neighbourhoods in the East End of London. The area is well-known for its popularity with migrants. During the nineteenth century, thousands of Europeans arrived as they escaped military service, oppression, economic depression, and increasingly dangerous conditions. Many came from the Russian Empire. The scale of the migration was extensive. As one correspondent noted:

We are face to face with a new Ghetto, one that has arisen during this generation, vastly greater in area than the old and different in character. It has absorbed the Mint, Whitechapel, and Stepney; it stretches out to Shoreditch, to Hackney, and to Stratford, and even across the river. In many streets in these districts four out of six names over the shops are Polish, German, or Russian, and the remainder are often Anglicized forms of foreign names. There are roads where scarce an English person is to be found, where the common speech is Yiddish, and where the majority of the adults speak only a little broken English. New immigrants settle here, 10, 20, or 30 thousand a year.4

Popular anxieties emerged in light of this migration and growing settlement, including overcrowding, displacement, and competition.5

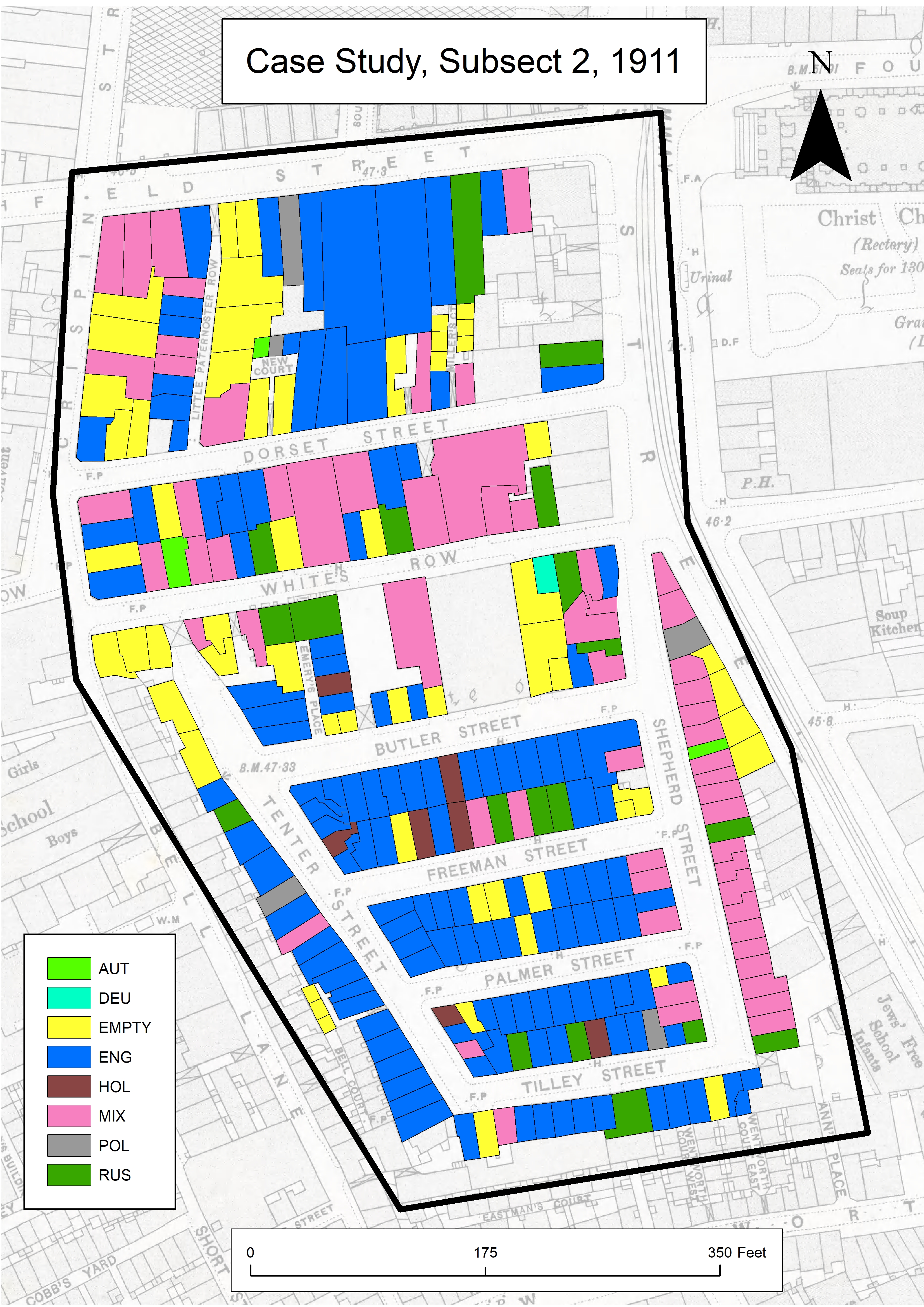

The neighbourhoods selected are subsections from the Whitechapel Registration district, as highlighted in the map of East London. The subsections are well suited for further analysis. Both experienced changes over time and diverged in their composition. When comparing the areas with George Arkell’s map of Jewish East London, the subsections sit on the boundaries of the Jewish community. The first subsect centres on Underwood Street in the north of the district, which contained 252 residential properties. Located between a series of major roads, subsect one remained well connected. Only Buttress Street led to a dead end. While North Place was an enclosed space, it had an additional small side passage back to Buxton Street. The second subsect is located around Dorset Street, on the district’s western fringes, and was comprised of 272 residential properties. The area included the Tenter Ground Estate and contained a number of lodging houses, shops, and industrial buildings.6 The area was densely populated and its residents suffered from poverty and overcrowding. The estate was essentially a cul-de-sac, and houses were small and cramped. The subsect contained a number of small courts, closes, and enclosed areas, which resulted in the streets becoming an important space for socialising and interacting.7 Although the subsections differed, they are representative of the local area.

III. Subsect One

The population of the Underwood Street area underwent profound change during the latter decades of the mid-late Victorian period. In 1881, there was a near total absence of foreign-born persons, with only a scattering of isolated migrants. By 1891, migrant clustering had begun to emerge. Portions of Buxton Street, Underwood Street, and Bakers Row (later Vallance Road), exhibited strong segregating behaviours amongst its migrant population. Yet, large numbers of properties remained solely inhabited by the native-born population. From 1901 onwards, the foreign-born population formed a distinctive residentially segregated area.

Some minor segregating behaviour existed between migrant groups. In 1901, the only two residences with Romanians living in them were situated next to each other on the corner of Buttress Street and Buxton Street. The dominance of Russian migrants and the ambiguity of national identity complicate any further analysis into inter-group segregation.

With the gradual expansion of the foreign-born community in nearby districts, the Buxton Street area became increasingly attractive for migrants. After spreading from its core in Whitechapel parish, increasing numbers of foreign-born migrants lived in adjacent districts and streets. Pressures on the existing housing stock, slum clearances, and the ability to afford more appropriate accommodation drove the migrant population to new areas. However, migrants moved seemingly in tandem with kin and kith groups, and pre-existing social networks.

On the south side of Underwood Street stood five large buildings composed of multiple dwellings, known as the Metropolitan Association Buildings. Throughout the period, the dwellings remained heavily dominated by native-born persons, as did many of the houses in the immediate vicinity. Persistent dominance by native-born persons might suggest a link to redlining, or the unwillingness amongst some landlords to rent to migrants, something to be explored further.

Decennial changes suggest migration into subsect one accelerated in the early 1900s, with North Place becoming a heavily segregated space. In a similar fashion, many houses on Buxton Street changed from being occupied by native-born to foreign-born persons. Crucially, the period 1881–1891 marked the introduction of migrants to the area, which was further amplified en masse in the following decade. The area rapidly absorbed migrants, and clear evidence of congregating can be observed in the map of 1911. Within thirty years, the neighbourhood underwent profound changes, with the population radically changing in composition.

IV. Subsect Two

The northern aspects of subsect two served as an isolated non-Jewish community. One of those streets, Dorset Street, has been described by Fiona Rule as the ‘worst street in London’ and was a notably transient space, with many lodging houses and poor slum housing.8 Running north from Dorset Street was Little Paternoster Row and two small-enclosed courts. Crimes, including murder, frequently occurred.9 The socio-economic composition of the population differed, as did the birthplaces of migrants, with a Dutch community present in subsect 2, and a predominantly Russian migrant community in subsect 1.

Segregation within the extent of subsect two was strongly evident in 1881. As illustrated in the maps of subset 2, at the time of the census in 1881, Little Paternoster Row was almost entirely composed of persons hailing from Poland. Meanwhile, Emery’s Place had a sizeable concentration of persons born in Holland. As time progressed, an increased number of native-born households emerged, which suggests either a return of native-born persons or second generation migrants establishing new households.

By 1911, a sizeable proportion of the remaining foreign-born population is residing in a cluster on one-side of Freeman Street. Overall, many properties became devoid of foreign-born persons in any of the households, undoubtedly as older migrants died or moved away, and were replaced by second-generation migrants or other native-born persons. A large number of properties retained a mixed composition in the absolute numbers of migrants, but they become increasingly outmatched by exclusively native-born residences.

Evidence exists to suggest a link between subsection one and two. In 1897, a group of over twenty Eastern European migrants were arrested at the home of a Bernard Green at 4 Underwood Street for illegal gambling. As was noted, ‘All were described by the police as foreign Jews, natives of Russian and Austrian Poland.’ The apprehended all gave addresses in Spitalfields, which included streets in subsect two.10

V.

Communities underwent profound changes; at times within a brief space of time. As Richard Cohen has noted, many Jewish migrants moved from ‘slow-moving’ contained communities to immense urban centres.11 The disorientation generated by their new environment likely enhanced the motivations to cluster together.

Within the two case studies, native communities reacted differently to the new arrivals. In the case of subsect one, migrants quickly displaced the native-born population in places, but it was limited to clustering behaviours, which expanded over the decades. In rows of houses such as Buttress Gardens, or in the eastern element of Underwood Street, properties remained overwhelmingly populated by native persons. Meanwhile, in other areas there was a near total absence of any native-born persons, being almost solely composed of migrants and their British-born kin. In contrast, subsect two revealed a complicated system whereby migrants and natives lived in proximity to each other. Extreme occurrences of segregation took place in isolated sub-streets, alleys, and closes.

A key finding is that subsect one rapidly gained a large migrant population and exhibited strongly segregationist behaviours. Meanwhile, subsect two began to lose its first generation migrant population. Similarly, the alleys and enclosed spaces of subsect two began to be populated and dominated by native-born persons, possibly as the migrant population moved on to other nearby areas. In their study of Vienna, Harriet Freidenreich has demonstrated that diverse migrant groups pursued different models of assimilation, with Galician Jews being far more segregated than other communities because of their distinct characteristics.12 A more extensive comparative analysis between migrant communities and geographical areas will reveal how typical the behaviours are.

To a certain extent, segregation was self-imposed. For many new arrivals it was necessary to be in proximity to unskilled work opportunities.13 There was also a religious and cultural dimension, with the need to be near to a synagogue and other institutions. It is now clear that the community was far from static with significant intercensal movements occurring. In the case of the Jewish Eastern Europeans, as David Newman has noted, new migrants often supplemented the existing communities.14 The constant stream of new arrivals contributed to the fluctuations on the border of the predominantly Eastern European migrant community. However, work remains to be done to establish whether these behaviours were comparable to that of other major cities, including New York, Paris, or Chicago.

Ultimately, the individualised approach to residential segregation offers a far greater degree of insight into the activities and composition of migrant communities. As demonstrated in these two case studies, aggregated analyses can mask localised experiences. While certainly more work, the level of detail in individual household geo-location is profound, and reveals distinct behaviours that we would otherwise fail to recognise.

Bibliography

Bermant, Chaim. London’s East End: Point of Arrival. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1975.

Carter, H., and S. Wheatley. “Residential Segregation in Nineteenth-Century Cities.” Area 12, no. 1 (1980): 57–62.

Cohen, Richard I. “Nostalgia and ‘return to the ghetto’: a cultural phenomenon in Western and Central Europe.” In Assimilation and Community: The Jews in Nineteenth-Century Europe, edited by Jonathan Frankel, Steven J. Zipperstein, 137–190. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Freidenreich, Harriet Pass. “Natives and Foreigners: Geographic Origins and Jewish Communal Politics in Interwar Vienna.” In Jewish Settlement and Community in the Modern Western World, edited by Ronald Dotterer, Deborah Dash Moore, and Steven M. Cohen, 117–131. Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Press, 1991.

Gartner, Lloyd P. “Notes on the Statistics of Jewish Immigration to England, 1870–1914.” Jewish Social Studies 22, no. 2 (1960): 97–102.

The Lancet. “Report of the Lancet Special Sanitary Commission on the Polish Colony of Jew Tailors.” May 3, 1884, 785–832.

Lloyd’s Illustrated Newspaper. “Raids on London Shops: A Baker’s Party.” June 13, 1897.

Newman, David. “Integration and Ethnic Spatial Concentration: The Changing Distribution of the Anglo-Jewish Community.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 10, no. 3 (1985): 360–376.

Rule, Fiona. The Worst Street in London. London: Ian Allen, 2008.

“The Tenter Ground Estate.” In Survey of London, vol. 27, Spitalfields and Mile End New Town, edited by F. H. W. Sheppard, 242–244. London: London County Council, 1957. Accessed 15 May 2018. British History. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol27/pp242-244.

The Times. “From A Correspondent. Alien London To-Day.” March 16, 1911.

The Times. “The Murder in The East-End.” June 20, 1901.

Data Sources

Schürer, Kevin and Edward Higgs, Integrated Census Microdata (I-CeM) Names and Addresses, 1851–1911: Special Licence Access, [data collection], UK Data Service, (2015), SN: 7856. Accessed 1 February 2018. http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-7856-1.

Data Access

The data used in this project is subject to stringent conditions of use and a special licence access must be secured to access the detailed records. Special arrangements are required to ensure that commercial sensitivity is protected. Data is held by the UK Data Service and access can be acquired through application. Further information can be found on the UK Data Service website.

Notes

-

Gartner, “Notes,” 102. ↩

-

Bermant, London’s East End, 122–123. ↩

-

Carter and Wheatley, “Residential Segregation,” 57–58. ↩

-

The Times, “From A Correspondent.” ↩

-

Bermant, London’s East End, 147–148. ↩

-

Sheppard, “The Tenter Ground Estate,” 242–244. ↩

-

Lancet, “Report,” 817–819. ↩

-

Rule, Worst Street. ↩

-

The Times, “The Murder in The East-End.” ↩

-

Lloyd’s Illustrated Newspaper, “Raids on London Shops: A Baker’s Party.” ↩

-

Cohen, “Nostalgia,” 131. ↩

-

Freidenreich, “Natives and Foreigners,” 118–120. ↩

-

Bermant, London’s East End, 161. ↩

-

Newman, “Integration,” 365. ↩

Author

James Perry,

Department of History, Lancaster University, james.perry@lancaster.ac.uk,