Mapping Mobility

Class and Spatial Mobility in the Wall Street Workforce, 1890–1914

Abstract

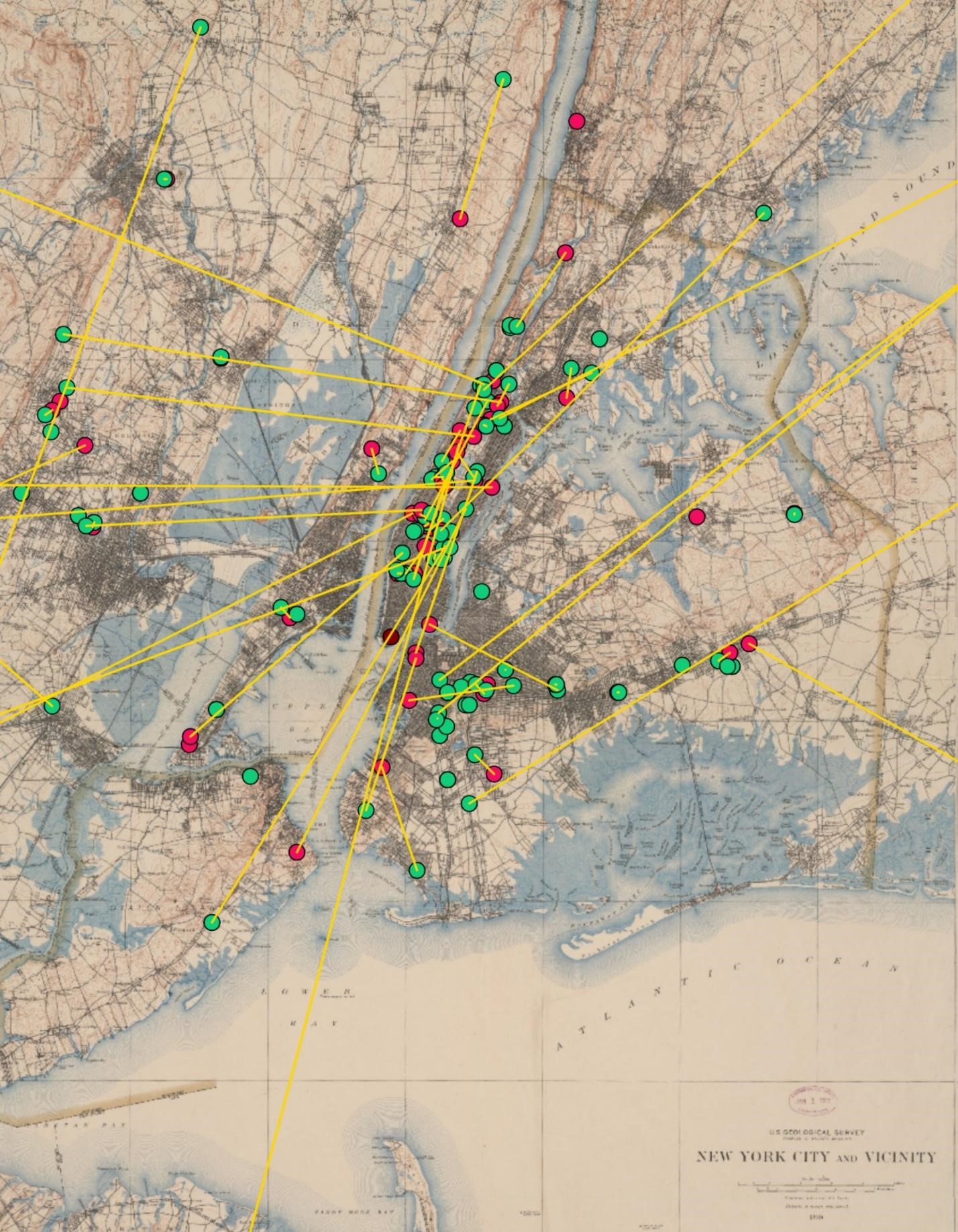

“Mapping Mobility” uses a database of the homes of the Wall Street workforce to shed light on the experiences of middle-class women and men who worked alongside each other but increasingly identified as city dwellers and suburbanites, respectively. Using the 1900 and 1910 U.S. Censuses, the project links residential records to trace the emergence of a gendered metropolitan landscape that would become an important cultural element in many American cities over the following decades. Tracing the mobility of male and female workers reveals a bifurcation between men whose movement to the suburbs was typically prompted by marriage and women who spent long periods of their lives in the workforce—almost always to support other relatives as family breadwinners. At the heart of this study is a database merging demographic data on more than 100 employees at Brown Brothers & Co., one of Wall Street’s most important investment banks in the Gilded Age, with salary data from the firm’s records held at the New-York Historical Society. The study uses linked records from the 1900 and 1910 Censuses to trace the dispersal of the Wall Street workforce throughout the New York metropolitan area. Wall Street workers were leaders of the charge towards the emergence of a male, suburban, white-collar workforce: in 1910, when only 16% of all clerical workers lived on the fringes of the United States’ metropolitan areas, 23% of New York’s banking workers lived there.1

Previous researchers into the lives of white-collar workers have usually had to decide whether to focus on the workplace or the home. White-collar workers tend to be broadly scattered, making data collection more difficult in an era before easily accessible digitized sources. Spatial analyses of the white-collar workforce have typically used microfilmed Census records, a cumbersome source base, to locate clusters of workers in specific neighborhoods and provide “thick description” of their everyday experiences.2 This approach, however, limits our understanding of workers’ mobility over time and the role of family structure in shaping class and geographic mobility for the white-collar middle class. Demographic analysis is particularly important to understand the trajectories white-collar workers saw among their peers and to determine how this shaped their aspirations. As powerful coalitions were emerging to “sort out” neighborhoods and establish impermeable boundaries between different categories of workers, white-collar men and women would have been particularly conscious of how their housing choices—or compromises—were likely to have repercussions for themselves and their families.3

In the late Gilded Age—the years between the depression of the 1890s (the United States’ largest before the Great Depression) and the outbreak of World War I—a major reorganization of the American economy occurred that centered on New York City’s capital markets. At its core were several thousand professional men who led Wall Street’s investment banks, brokerages, law offices and accounting firms and oversaw the movement of hundreds of millions of dollars in and out of the financial district each year.4 These professional firms, in turn, depended on the labor of tens of thousands of clerical workers who acted as the behind-the-scenes “stagehands” of the economy.5 To recover the experience of ordinary salaried workers who left behind few records that are easy to retrieve, this project uses the Brown Bros. data as the basis for a website that takes in multiple scales of analysis, from digitized neighborhood maps and college reunion yearbooks to family histories uploaded to the Internet. The results of this metropolitan methodology can be explored by visiting “Mapping Mobility,” a companion website to this article, which uses a 1901 map of the New York metropolitan area as a device for displaying the migrations of the Brown Bros. workforce and incorporates brief biographies of each of the staff members found in the Census data.6

Understanding women workers’ role in this process has been particularly difficult due to a dearth of personal documents. The Brown Brothers records provided a new way to examine this question. The firm had been an important marketer of Southern cotton in the antebellum years but hesitated to participate in the railroad and industrial booms of the Gilded Age, allowing “others…[to] reap a rich harvest in which the firm would have shared,” as one partner later lamented.7 Although Brown Brothers declined relative to firms like J.P. Morgan & Co., it had its own office building at 59 Wall Street, a “marble palazzo” built to its specifications in 1865 and expanded in the 1880s to seven floors.8 Like many other Gilded Age firms, it had to adapt to business opportunities made possible by a more robust communication network and burgeoning flows of information, growing between the late 1890s and 1910 from 40-something to over 100 employees.9

The firm sought out new groups of workers to fill these needs, such as white men from non-“Anglo-Saxon” backgrounds—a trait that distinguished New York firms from employers elsewhere.10 Employees hired in the 1870s included men from elite New York families like the Hones and LeRoys; by the 1910s, however, the roster included surnames like Appleberg, Butzow, and Montanye. Similarly, in 1897 the firm hired its first three female stenographers, and within months partner James Brown was declaring “I can scarcely understand how we did our business without women.”11 Compiling names and salary information from the ledgers and combining this data with records retrieved from digitized, text-searchable 1900 and 1910 federal censuses on Ancestry.com was one way to understand how women took advantage of these new opportunities. Of the 123 people who worked at Brown Bros. in either 1900 or 1910, at least one record was found for 115 individuals (93%), and for 72 individuals (59%) records were found in both 1900 and 1910. A total of 187 records were found, or 76% of the potential total (246, = 123 x 2). These retrieval rates are roughly comparable with other published studies of migration that use demographic records.12 Three-quarters of the 20 women working at Brown Bros. in either 1900 or 1910 were found in both Censuses.

Summary of Brown Bros. Census records database

| Total | Subtotal | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two records found: | 72 | 57 | 15 | |

| —— In workforce both years | 49 | 42 | 7 | |

| —— Married women not in workforce both years | 3 | 3 | ||

| —— In school in 1900 | 20 | 15 | 5 | |

| Only one record found: | 43 | 40 | 3 | |

| —— School age | 10 | 10 | ||

| —— Emigrated, immigrated, or died | 4 | 4 | ||

| No records found | 8 | 6 | 2 | |

| Total number of employees | 123 | 103 | 20 |

Data on the 49 employees who were in the American workforce in both 1900 and 1910 sheds light on the development of a metropolitan landscape shaped by gender.13 None of the seven women in the workforce in both years lived in suburban New York; meanwhile, 43% of men were living in the suburbs by 1910.14 Instead, all the women lived in urban areas of the metropolis—four in Brooklyn and three in Manhattan. While descriptions of white-collar women regularly questioned if they were shirking their destiny to become wives and mothers, closer examination of the seven women’s households suggests their decision to work was attributable to fulfilling familial obligations. The average salary of female Brown Bros. workers was $1,000, far higher than what stenographers in other cities earned and also than the $800 mark considered a desirable working-class “family wage.”15 At a time when one in five working women in New York was a boarder or a lodger, all seven women lived with family members.16 In fact, among the eighteen women workers found in the database, only one, Florence M. Bryan, was recorded as living in New York independently. Put simply, rather than being “adrift,” as the contemporary stereotype would have it, white-collar women were more likely to be attached to their families.

The handful of experiences in the Brown Bros. data suggest that women in the white-collar workforce took on responsibility for their relatives that might well entail moving a considerable distance. This attachment produced two different patterns in the data. One pattern was of class stasis: the four working women who lived in urban New York in both years were in the same houses in 1910 as they had been in 1900, and all were living with family members. In a period when moving indicated class mobility, this suggests women’s salaries were necessary for maintaining their families’ homes and status. The other pattern found is of women moving with or joining family members in New York City. Frances Kingsland, for example, a schoolteacher in western New York in 1900, moved to Harlem with her widowed mother; Helen Heydinger, who in 1900 was a stenographer living on her own in Boston, a decade later was working at Brown Bros. and living with her mother in downtown Brooklyn.17 Daughters likely felt stronger pressure to remain with their older relatives while sons were encouraged to pursue careers independently; they were seen as fulfilling their “natural” role as homemakers even as they left the home to earn the income to sustain it.18

Meredith Waterbury’s experiences further illustrate this pattern. Waterbury, who joined the firm in 1904 and became the head of its stenography department in 1909, was a unique example of an adult woman who was not in the workforce in 1900 but later entered it. In 1900, she was living near West 131st Street in Harlem with her husband, Sherman, a jewelry salesman. The 1905 New York State Census shows the couple living on West 140th Street with a two-year-old son, Chester. Then, in the 1910 Census, Meredith Waterbury is recorded living near 145th Street in Harlem with the now seven-year-old Chester. Further searching reveals Sherman Waterbury was still living at the building where the family was recorded in 1905. This indicates the couple had separated and Meredith Waterbury was using her salary of over $1,100 to support herself and her son.

The women whose salaries supported their families were not acknowledged as “breadwinners” and the Brown Bros. salary data show that while they were often hired with larger salaries than men they were less likely than men to enjoy substantial salary increases over the following years. The digitized government records available within Ancestry.com suggest that working women turned to each other for support. Thus, the 1915 New York state census reveals that Meredith Waterbury and Gertrude Hulst, who had worked alongside her at Brown Bros. from 1906 to 1909, were lodgers of a family living on West 70th Street.19 Similarly, a digitized U.S. State Department passport shows that when Waterbury sought to become an American Red Cross nurse in France in summer 1917, she turned to Amelia A. Thompson, another stenographer at Brown Bros., to affirm her identity.20 Thompson, in turn, was recorded in a 1928 passenger manifest returning from a cruise to Bermuda alongside her colleague Isobel Law.21 These linkages suggest that mutual material and social support was one way women workers managed the inequitable pay structure of the workplace and the pull of family obligations at home.22

The development of a metropolitan white-collar workforce in which gender shaped where men and women lived was largely ignored. Newspaper articles on female clerks tended to emphasize the housing problems of unmarried urban newcomers and suggested these would be resolved as they married and left the workforce. The circulation of stories about women taking clerical jobs to find a wealthy husband helped reinforce this framing.23 Cumulatively, this had the effect of relieving journalists, policymakers, and the public from considering the role of gender ideology in shaping men’s and women’s mobility. It also made women who spent long careers living in urban neighborhoods and working in the white-collar workforce largely invisible.24

Similar forms of structural discrimination have shaped the uses of the historical evidence. Little work has been done to substantiate or refute the assumption that office work was only a temporary occupation for women.25 Presumptions about the difficulty of finding women who changed their names on marriage shapes research in the present, even when digital methods are used: a recent paper on using machine learning to automate Census linking regretfully concludes that linking women is a difficulty that cannot yet be surmounted.26 Yet this small study suggests that linking women over time in digitized records is not an insurmountable problem. Unless historians participate more vigorously in the discussion of how digital methodologies will be applied to old records, we are likely to continue to rely on suppositions about women’s lives—and all people’s lives—based on imperfectly gathered evidence.

Bibliography

Abelson, Elaine S. “The Times that Tried Only Men’s Souls: Women, Work, and Public Policy in the Great Depression.” In Women on Their Own: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Being Single, edited by Rudolph M. Bell and Virginia Yans, 219–238. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2008.

Bjelopera, Jerome P. City of Clerks: Office and Sales Workers in Philadelphia, 1870–1920. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2005.

Brown, James. “Report for Year Ending Dec. 31st, 1897.” Brown Brothers Harriman Records, box 79, folder 9. New-York Historical Society, New York.

Brown, John Crosby. A Hundred Years of Merchant Banking: A History of Brown Brothers and Company, Brown, Shipley & Company and the Allied Firms. New York: Privately printed, 1909.

Carosso, Vincent P. and Rose C. Carosso. The Morgans: Private International Bankers, 1854–1913. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Davis, Clark. Company Men: White-Collar Life and Corporate Cultures in Los Angeles, 1892–1941. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

Feigenbaum, James. “A Machine Learning Approach to Census Record Linking” (working paper, March 28, 2016). https://jamesfeigenbaum.github.io/research/.

Glenn, Evelyn Nakano. Forced to Care: Coercion and Caregiving in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Hanchett, Thomas W. Sorting Out the New South City: Race, Class, and Urban Development in Charlotte, 1875–1975. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Kwolek-Folland, Angel. Engendering Business: Men and Women in the Corporate Office, 1870–1930. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994.

Landau, Sarah Bradford, and Carl W. Condit. Rise of the New York Skyscraper, 1865–1913. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996.

Meyerowitz, Joanne. Women Adrift: Independent Wage Earners in Chicago, 1880–1930. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Mihm, Stephen. “Clerks, Classes and Conflicts: A Response to Michael Zakim’s ‘The Business Clerk as Social Revolutionary,’” Journal of the Early Republic 26, no. 4 (Winter 2006): 605–625.

Mitchell, Lawrence E. The Speculation Economy: How Finance Triumphed over Industry. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2007.

New York Passenger Lists, 1820–1957. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com, 2010. Accessed May 21, 2018. https://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=7488.

New York State Census, 1915. Provo, UT: Ancestry.com, 2012. Accessed May 21, 2018. https://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=2703.

O’Sullivan, Mary A. Dividends of Development: Securities Markets in the History of U.S. Capitalism, 1866–1922. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Olson, Sherry. “Ladders of Mobility in a Fast-Growing Industrial City: Two by Two and Twenty Years Later.” In Lives in Transition: Longitudinal Analysis from Historical Sources, edited by Peter A. Baskerville and Kris E. Inwood, 189–210. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015.

Pak, Susie. Gentlemen Bankers: The World of J.P. Morgan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013.

Pertilla, Atiba. “Mapping Mobility: Class and Spatial Mobility in the Wall Street Workforce, 1890–1914.” Updated May 25, 2018. http://gscho.net/scalar/mapping-clerks/index.

Ruggles, Steven, Katie Genadek, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, and Matthew Sobek. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 7.0. Accessed May 21, 2018. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V7.0.

Srole, Carole. Transcribing Class and Gender: Masculinity and Femininity in Nineteenth-Century Courts and Offices. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2010.

U.S. Passport Applications, 1795–1925. Lehi, UT: Ancestry.com, 2007. Accessed May 21, 2018. https://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=1174.

Vapnek, Lara. Breadwinners: Working Women and Economic Independence, 1865–1920. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2009.

Wallace, Mike. Greater Gotham: A History of New York City from 1898 to 1919. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Notes

-

Based on Ruggles et al., Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, 1910 1% Sample. ↩

-

Davis, Company Men, 84–90; Bjelopera, City of Clerks, 142–161. ↩

-

Hanchett, Sorting Out the New South City. ↩

-

O’Sullivan, Dividends of Development; Mitchell, The Speculation Economy; Pak, Gentlemen Bankers. ↩

-

Mihm, “Clerks, Classes and Conflicts,” 610. ↩

-

See Pertilla, “Mapping Mobility.” ↩

-

Brown, A Hundred Years, 294. ↩

-

Landau and Condit, Rise of the New York Skyscraper, 55–56. ↩

-

Kwolek-Folland, Engendering Business, 15–40; Carosso and Carosso, The Morgans; Pak, Gentlemen Bankers. ↩

-

Davis, Company Men, 69–76. ↩

-

Brown, “Report for Year Ending Dec. 31st, 1897.” ↩

-

See Olson, “Ladders of Mobility,” 196–199. ↩

-

This amounts to 49 of the 123 individuals in the Brown Bros. records. About a quarter of the individuals working at the firm in 1910 had been school-age children a decade earlier. In tracing employees back to the 1900 Census, I focused on those who were teenagers or older in 1900 and thus more likely to be in the workforce. Additional searching would probably find more future employees but with a diminishing return on the time spent. ↩

-

The category of “Urban New York” includes Manhattan, Brooklyn, Jersey City and Newark; “Suburban New York” includes Bergen, Essex, Hudson, Middlesex, Passaic, Somerset and Union Counties in New Jersey, the boroughs of the Bronx, Queens, and Staten Island, and Nassau and Westchester Counties in New York. ↩

-

Wallace, Greater Gotham, 534; Srole, Transcribing, 167–168. ↩

-

For discussion of the trope of the “ambitious” and independent female stenographer, see Srole, Transcribing, 160–166. Statistics on boarding: Meyerowitz, Women Adrift, 4. ↩

-

Vapnek, Breadwinners, 34–65. ↩

-

Glenn, Forced to Care, 20–25, 88–91. ↩

-

New York State Census, 1915, census schedule for New York, N.Y., assembly district 15, election district 7, p. 19. Ancestry.com. ↩

-

U.S. Passport Applications, certificate #63830, August 29, 1917. Ancestry.com. Sherman Waterbury, her estranged husband, died in 1918. ↩

-

New York Passenger Lists, 1820–1957, S.S. Bermuda, Nov. 29, 1928. Ancestry.com. ↩

-

Organizations for women in white-collar jobs began to appear in New York in the early 1900s, but they were typically oriented towards female professionals or entrepreneurs rather than clerical workers. ↩

-

Kwolek-Folland, Engendering, 63–66; Srole, Transcribing, 146–151. In the Brown Bros. records there is only one example of two employees marrying each other. ↩

-

Abelson, “The Times That Tried Only Men’s Souls.” ↩

-

Meyerowitz, Women Adrift, 144. ↩

-

Feigenbaum, “A Machine Learning Approach,” 8. ↩

Appendix

Author

Atiba Pertilla,

German Historical Institute, pertilla@gscho.net,