Mapping the Media Landscape in Old Regime France

Citation Practices and Social Reading in the Affiches, 1770–1788

Abstract

Readers in eighteenth-century France witnessed both the slow rise of literacy and the rapid growth in both the quantity and variety of print. Historians of Early Modern Europe have investigated existing diaries and private correspondence in order to understand the ways a particular individual responded to this age of expanding print culture. Yet, for studying the responses of the general reading public, historians have relatively less sources to work with. It remains rather difficult to study what people living in the eighteenth century thought about what they read, especially at any kind of large scale. My research presents a new approach: the study of readers’ letters in newspapers published throughout France between 1770–1791. This article explores how the practices that readers and publishers employed to reference print matter helped the reading public conceptualize connections between the text they were reading and the larger media landscape.

Historians of the book have investigated extensively what publications were accessible to eighteenth-century readers. They have also traced the circulation of publications, and that work has shed light on who owned books, and in many cases, the exact titles that people purchased. Drawing upon wills, bankruptcy records, auction catalogs, and publishing house records, historians have reconstructed the shifts in print consumption patterns over the course of the century. The work on the clandestine book trade in France is particularly extensive; such books were published outside of France to avoid censorship, although they were sold widely in France.1 In short, historians know a great deal about this era of print saturation, and in particular, what books people purchased, sold, and passed down. But then as now, owning a book did not necessarily mean one had read it. Even if one did read a particular book, what each reader made of the text varied considerably.2

The sources under study have received little scholarly attention, but they are nevertheless particularly well suited to the study of reception in the eighteenth century: the thousands of letters to the editor published in French newspapers in the last decades of the Old Regime. The first French daily newspaper, the Journal de Paris, began publication in 1777. It followed the format of the short newspapers titled affiches, annonces, et avis divers, generally known as affiches, that were published throughout the kingdom from the 1770s and into the first years of the French Revolution. This paper builds upon my book manuscript, which is a study of the affiches and the engagement of their readers, and which traces the themes and questions that readers brought to the paper as they puzzled through what it meant to live in an age of enlightenment. Within the approximately 7,000 letters under study, writers discussed what they had read, and they reacted to texts. They cited books and other newspapers, and they cited one another. What is more, the editors re-published letters that had appeared in other newspapers, which they indicated in an editorial note that cited the publication.3 But they also cut and pasted sentences, paragraphs, or entire articles without attributing the content.

The newspapers also hold promise for further digital history research. First, with a team of undergraduate students, we are converting the images of the letters to the editor into text files suitable for text analysis. This effort is ongoing.4 Second, I am building a database of the approximately 7,000 letters. The sources are rich in metadata, which include location data (where it was written, published, republished), prosopographical data (the author’s name, pen name, social position, profession, and linked data like VIAF numbers of known authors5), and the relationships to books and ideas (books cited, newspapers cited, and the other newspapers that printed the same letter).

This research engages with one of the cardinal topics in the field: the reception of Enlightenment ideas and the nature of their link to the Revolution that followed. Digital history and computational tools like text analysis and network analysis are well-suited to this historiographic debate, because they allow the historian to consider the connections between writers and readers, and between print ephemera and books, in new ways.

The readers and the editors of the affiches described the periodicals as an ongoing dialogue. Editors asked their readers to contribute their opinions on certain topics, and readers responded to the editors and to one another. Indeed, editors would print serialized debates between readers on a range of subject manner, such as the merits of inoculation, the safety of bathing an infant in cold water, or whether women should be so vocal in the paper. In their responses, they referenced articles in the paper, books, or other publications that had inspired their response. The citation practices between newspapers, where readers reacted to content they had read in a periodical, show that rather than writing to that particular periodical for their response, readers wrote instead to their local affiches. The practice was employed by a subset of the affiches in the dataset, which included the newspapers published in Paris, Toulouse, Troyes, Grenoble, Marseille, Amiens, Angers, Rouen, and Dijon, and only by a small proportion of writers. In fact, about one percent of the letters in the corpus of 7,000 reacted to a periodical other than the one to which they addressed their letter.

While the present paper concerns 1% of the larger corpus of letters, this citation practice nevertheless merits study. First, citing other newspapers was an important counterbalance to the other citation approaches that editors and writers used, such as referencing books, referring to previous articles in the same affiches, or recommending other print matter available in the shop of the editor (who was often also a printer-bookseller).

Moreover, this investigation lends further insight into the reading practices of the day. While many men and women read the local affiches in isolation, the signaling by editors and readers through republication, book references, and citations of articles are nevertheless important, because they pointed the readers' attention toward a wider world of print—a world that was shaped by the social nature of reading in the eighteenth century, when many accessed periodicals in shared spaces like reading rooms and cafés.6

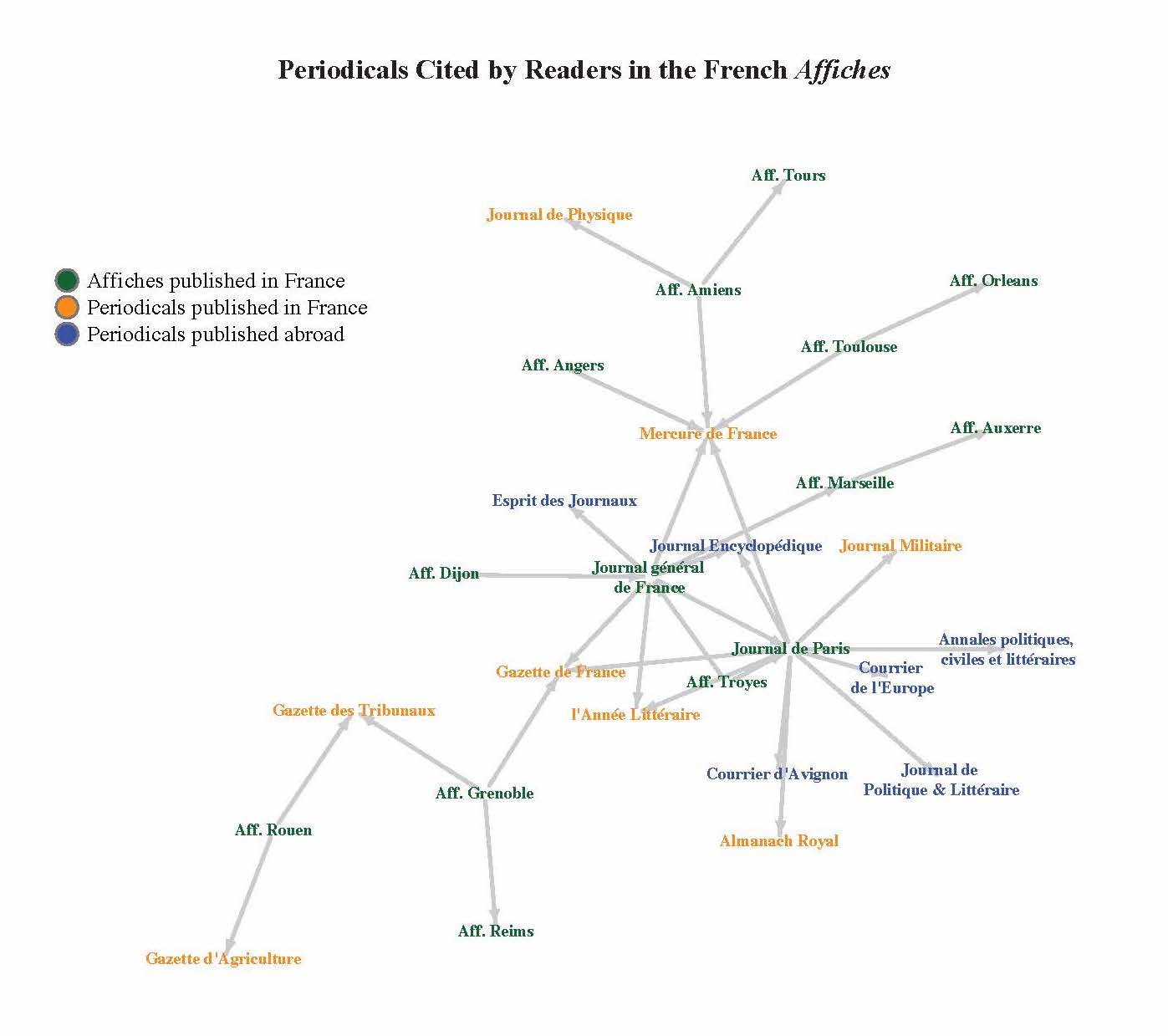

To track the publications that letter writers responded to, I have visualized them in figure 1 as a network. A network plot is an apt visualization tool in this case, because it allows the historian to map relationships—in this case, information sharing—in ways that are not tied to space. The media landscape mapped here is a conceptual one that traces the publications French readers consumed alongside the affiches. Figure 1 illustrates the links between local, national, international, and more specialized information. The nodes at the center of figure 1 show a cluster of literary periodicals that included two literary journals published in France: the Mercure de France, run by the prominent publisher, Charles-Joseph Panckoucke, and L’Année Littéraire, a more conservative publication by Élie Fréron, who often debated Voltaire and other philosophes. The Gazette de France, which published short, censored news reports on geopolitical matters, was referenced by Parisian and provincial affiches. Readers responded to specialized periodicals on jurisprudence (Gazette des Tribunaux), military news and tactical history (Journal Militaire), and medicine and the sciences (Journal de Physique). The readers of the affiches also reacted to uncensored papers published abroad in Brussels, Liège, and London that commented on politics in France, including the Journal de Politique et Littéraire, the Annales politiques, civiles et littéraire, and the Esprit des Journaux.7

Such literary and political publications were central in readers’ citations, especially among those who wrote to the Parisian newspapers and to the Affiches de Troyes. Moreover, the citation patterns of readers differed in noteworthy ways from the republication practices of the affiches’ editors. Editors were less apt to pick up content from specialized journals or international newspapers and re-publish it in their own affiches with frequency, even though such periodicals did publish letters to the editor. Instead, editors drew their republished content from the surrounding towns and cities, privileging regional concerns.8 By contrast, readers that cited newspapers drew upon content from further afield, and in particular from newspapers published outside of France. Under the Old Regime, several newspapers were published “abroad,” and listed London, Brussels, or Liège—and on occasion Paris—as their site of publication.9 Historians of the press have questioned whether all such newspapers made for a French audience were in fact published abroad, or whether they sometimes printed in France and simply indicated an international publication site in order to escape censorship by the French government.

The network plot of reader citations presented here renders a picture of the French reading public that is much less regional in its orientation. The centrality of literary and political newspapers underscores that Parisian and international publications were read and discussed in provincial centers. But moreover, it reveals integration between literary and political periodicals that were considered more erudite and the readership of the more practical, commercially oriented affiches.10 While newspaper editors tended to respond to and reprint content focused on regional concerns by drawing on affiches and specialized publications from the surrounding provinces, this paper demonstrates that readers adopted a more expansive approach to information sharing that was less tied to local geographies and concerns. When readers cited other periodicals in their letters, they tended to cite national and international literary and political periodicals. While previous studies of the affiches have emphasized their lack of political content, this paper demonstrates that readers of the affiches did access literary content, specialist knowledge, and political information that was international in scope.

The network analysis of shared newspaper content sheds new light on the history of print culture. First, figure 1 shows that readers were not consuming the affiches in isolation. Indeed, the affiches were part of a larger world of print; and readers and editors shaped this vision of the paper through their citation practices. Second, the practice of reacting to one paper by writing a public letter to another is a reflection of the ways people in the eighteenth century read—reading, after all, was a social, collaborative undertaking. People consumed the newspapers studied here in homes, reading rooms, cafes, and bookstores where other periodicals were available, and their references serve as reminders of this material context. Moreover, readers and editors used the affiches in their town as a way to stimulate local discussion around a particular topic that had appeared in a more specialized journal. They also cited newspaper content from uncensored publications. The prevalence of uncensored literary and political publications cited in the provincial affiches indicates that readers were aware of more political news than one might anticipate from reading the censored affiches from a particular town alone. More broadly, when compared to the wide range of books cited, the references to newspapers converged more around a shared collection of popular periodicals.

Network analysis also offers insight into reading practices in the eighteenth century. The references that form the ties between periodicals in the network illustrate how readers established their authority as writers, tagged the people they were trying to talk to, and signaled to the reader and the publication how such information was connected to other works. Men and women living in Paris and in the provinces alike accessed literary and political criticism. For historians of the Old Regime and the Revolution that followed, the affiches offer a window into the political education of the French reading public.

Bibliography

Bond, Elizabeth Andrews. “Circuits of Practical Knowledge: The Network of Letters to the Editor in the French Provincial Press, 1770–1788.” French Historical Studies 39, no. 3 (August 2016): 535–565. https://doi.org/10.1215/00161071-3500309.

Burrows, Simon. Blackmail, Scandal, and Revolution: London’s French libellistes, 1758–1792. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006.

Causer, Tim and Valerie Wallace. “Building a Volunteer Community: Results and Findings from Transcribe Bentham.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 6, no. 2 (2012). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/6/2/000125/000125.html.

Censer, Jack. The French Press in the Age of Enlightenment. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Cordell, Ryan, and Abby Mullen. “‘Fugitive Verses’: The Circulation of Poems in Nineteenth-Century American Newspapers.” American Periodicals: A Journal of History & Criticism 27, no. 1 (April 2017): 29–52.

Curran, Mark. “Beyond the Forbidden Best-Sellers of Pre-Revolutionary France.” The Historical Journal 56, no. 1 (2013): 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X12000556.

Darnton, Robert. The Literary Underground of the Old Regime. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982.

Darnton, Robert. “Readers Respond to Rousseau.” In The Great Cat Massacre and other Episodes in French Cultural History, 215—256. New York: Basic Books, 1984.

Furet, François and Jacques Ozouf. Lire et écrire: l’alphabétisation des Français de Calvin à Jules Ferry. 2 vols. Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1985.

Gruder, Vivian. The Notables and the Nation: The Political Schooling of the French, 1787–1788. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007.

Labrosse, Claude. Lire au XVIIIe siècle: la Nouvelle Héloïse et ses lecteurs. Lyon: Presses universitaires de Lyon, 1985.

The Multigraph Collective. Interacting with Print: Elements of Reading in the Era of Print Saturation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Popkin, Jeremy D. News and Politics in the Age of Revolution: Jean Luzac’s Gazette de Leyde. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989.

Roche, Daniel. Le peuple de Paris: essai sur la culture populaire au XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Aubier Montaigne, 1981.

Sgard, Jean. “Dictionnaire des Journaux: Édition électronique revue, corrigée et augmentée du Dictionnaire des Journaux (1600–1789).” Hosted by the Institut des sciences de l’Homme. Accessed May 1, 2018. http://dictionnaire-journaux.gazettes18e.fr/.

Slauter, Will. “Le paragraphe mobile.” Annales. Histoire, sciences sociales 67, no. 2 (2012): 363–389. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23211634.

Strange, Carolyn, Daniel McNamara, Josh Wodak, and Ian Wood. “Mining for the Meanings of a Murder: The Impact of OCR Quality on the Use of Digitized Historical Newspapers.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 8, no. 1 (2014). http://digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/8/1/000168/000168.html.

Williams, Abigail. The Social Life of Books: Reading Together in the Eighteenth-Century Home. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

Notes

-

Among the landmark studies in this field, see, especially Furet et al., Lire et écrire; Roche, Le Peuple de Paris; Darnton, The Literary Underground; and more recent reevaluations, Curran, “Beyond the Forbidden Best-Sellers,” 89–112; Multigraph Collective, Interacting with Print. ↩

-

Research on readers’ responses to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Julie, ou La Nouvelle Heloïse, one of the most popular books of the period, is particularly extensive. Darnton, “Readers Respond,” 215–256; and Labrosse, Lire au XVIIIe siècle. ↩

-

This project is informed by scholarship on editorial citation, authorship, and republication practices in the eighteenth-and nineteenth-century press, which has demonstrated that reuse of newspaper content spanned the Atlantic world through information networks between publications. Cordell et al., “Fugitive Verses,” 29–52; Slauter, “Paragraphe Mobile,” 363–389. ↩

-

The digitization of the content of the nearly 7,000 letters now underway will make possible a range of further text analysis of the source material. Such studies include: tracing what information “went viral” and how it spread; topic modeling the content of the affiches; and investigating shifts in discourse that corresponded with key institutional and political changes during the early years of the French Revolution.

Owing to the image quality of the files under study, the most appropriate digitization method for the sources is transcription. Initial trials using OCR software on a sample of the letters introduced too many errors into the text files. Correction of the OCR results was more time consuming than manually transcribing the content. For a discussion of best practices in crowdsourced transcription, see Causer et al., “Building a Volunteer Community”; Strange et al., “Mining for Meanings of a Murder.” ↩

-

Virtual International Authority File numbers are unique identifiers assigned to authors across library databases. For further information on VIAF numbers, see https://viaf.org/. ↩

-

Reading in the eighteenth century was a social activity. Williams, Social Life, 110–125. Vivian Gruder has located pamphlets and periodicals—including the affiches—in French reading rooms and cafés, which formed a key locus of political education for the French reading public. Gruder, Notables and Nation, 196–207. ↩

-

Sgard, Dictionnaire de la Presse. ↩

-

Bond, “Circuits of Practical Knowledge,” 555–561. ↩

-

Jeremy Popkin and Simon Burrows have written on publications produced outside of French borders for a French audience. Popkin, News and Politics in an Age of Revolution; Burrows, Blackmail, Scandal, and Revolution. ↩

-

Jack Censer has suggested that the affiches were more conservative in political orientation, because the censored papers supported the powerful institutions of the Church and the Bourbon monarchy, and limited the content concerning the working classes. Censer, French Press, 54–65. ↩

Author

Elizabeth Andrews Bond,

Department of History, Ohio State University, bond.282@osu.edu,