“The Two Diseases Are So Utterly Dissimilar”

Using Digital Humanities Tools to Advance Scholarship in the Global History of Medicine

Abstract

On December 15, 1889, the Omaha Daily Bee newspaper quoted a French physician, Dr. Albert Robin of the Academy of Medicine, about the possible relationship between the influenza epidemic spreading across Europe and a future outbreak of cholera: “The theory has been advanced that the influenza is the forerunner of cholera, but I regard that as pure nonsense.” Robin stated that although at various times “an influenza epidemic has been closely followed by a visitation of the cholera,” it is equally true that “several times in the same century there has been an epidemic of influenza with no cholera following, just as there have been epidemics of cholera with no influenza preceding.” Robin concluded: “The fact is that the two diseases are so utterly dissimilar as to make any such sequence all but impossible, and any occasional instances of their simultaneous appearance must be regarded as mere coincidences, with no deeper significance in the matter of treatment.”1

Analyzing this statement by Robin using a digital humanities approach can enhance scholarly understanding of significant questions about the functioning of medical networks on a global scale; the relationship between expert knowledge and public understanding; and the role of new technologies in shaping beliefs and attitudes. In this example, an American newspaper quoted a European expert invoking scientific knowledge of how diseases are transmitted in order to reassure the public about a public health threat. Just as the relatively new technologies of global news reporting by transoceanic cables allowed for rapid transmission of information on a global scale in 1889, the availability of digitized collections of newspapers with full text search capacity allows the historian to quickly and thoroughly track the spread of information on a global scale. Locating the article cited here from the Omaha Daily Bee through a keyword proximity search of digitized newspapers is an example of how digital humanities tools have transformed historical analysis.2 The Russian influenza, which first received broad attention in St. Petersburg in November 1889 and spread across Europe and into the Americas over the next two months, occurred at a critical moment in the development of mass journalism, medical knowledge, and information technology, as the telegraph allowed news to spread faster than diseases at the same time that bacteriological research revealed distinct paths of contagion.3 The fact that a daily newspaper in Nebraska published an interview with a French scientist was very common in this historical context where public discourse included extensive international reporting on medical topics. Yet Robin’s dismissal as “pure nonsense” the prediction that influenza would lead to cholera raises historical questions best addressed through methods of close reading, contextual analysis, and layered interpretation.

In fact, this question of whether “influenza is the forerunner of cholera” was prompted by a single statement by Russian physician Nikolai Fedorovich Zdekauer.4 As reported in the St Petersburg daily newspaper, Novoe Vremia, on November 18 [29], 1889, Zdekauer told the Society for the Improvement of Public Health that influenza could be followed by an even greater threat to public health:

With great interest those in attendance listened to the opinion of the authoritative scientist, prof. N. O. Zdekauer, who appeared in the middle of the symposium. Prof. Zdekauer notes that influenza on its own is not dangerous, but there are circumstances that make it necessary to think seriously about influenza. During his many years, he lived through 4 choleras and each of these choleras were preceded by influenza and it is possible to imagine that this epidemic is a precursor to that cholera that comes to us from Asia. Moving from Turkey to Syria, Mesopotamia, this cholera is now coming from Persia. There are suppositions that the influenza microbe, having survived the winter in our soil, may develop into cholera in the spring. In this consideration, warned Zdekauer, we need to pay attention to improving the health of the city, as the experiences of 1830, 1848, 1865, and 1884 show that even a quarantine does not guarantee the end of cholera. The most recent choleras develop most of all in Spain and Italy, countries with more positive conditions in terms of sanitation. Cholera almost never appears in England, a country with excellent sanitary conditions.5

The potential impact of this comment became evident in the first international report published on December 2, 1889 in the London Standard:

At the meeting yesterday of the Russian Association for the Preservation of the Public Health, Professor Zdekaner [sic], the first authority in Russia, said he had witnessed five epidemics of cholera, each of which was preceded by an epidemic of influenza such as that now raging. He considered it highly probable that the present disease would be succeeded by cholera next Spring. He called on the authorities, therefore, to undertake at once such sanitary measures as had led to such excellent results in England.6

On the same day, the St. Paul Daily Globe offered a slightly abbreviated report under the ominous headline, “Forerunner of Cholera”: “Prof. Zdenecker [sic], one of the leading Russian medical authorities, declares his belief that the influenza now prevailing here is a forerunner of cholera. The same signs, he says, preceded the last five cholera epidemics here.”7

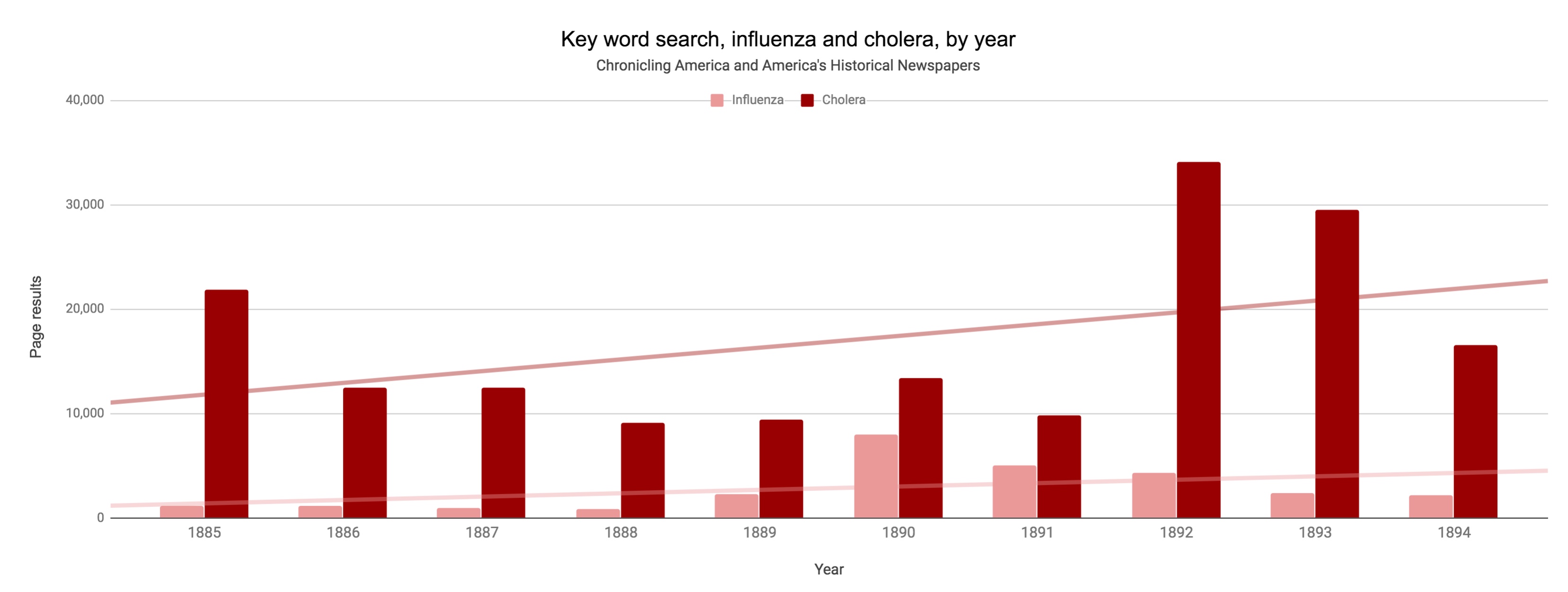

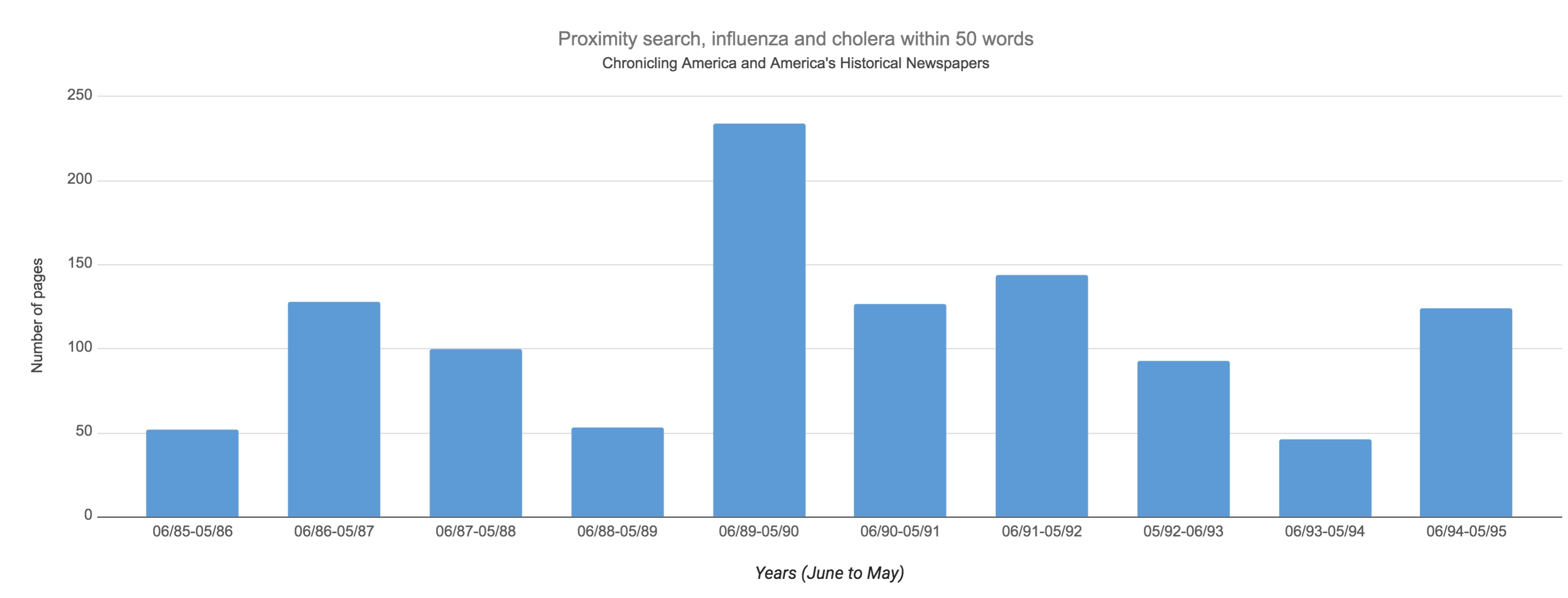

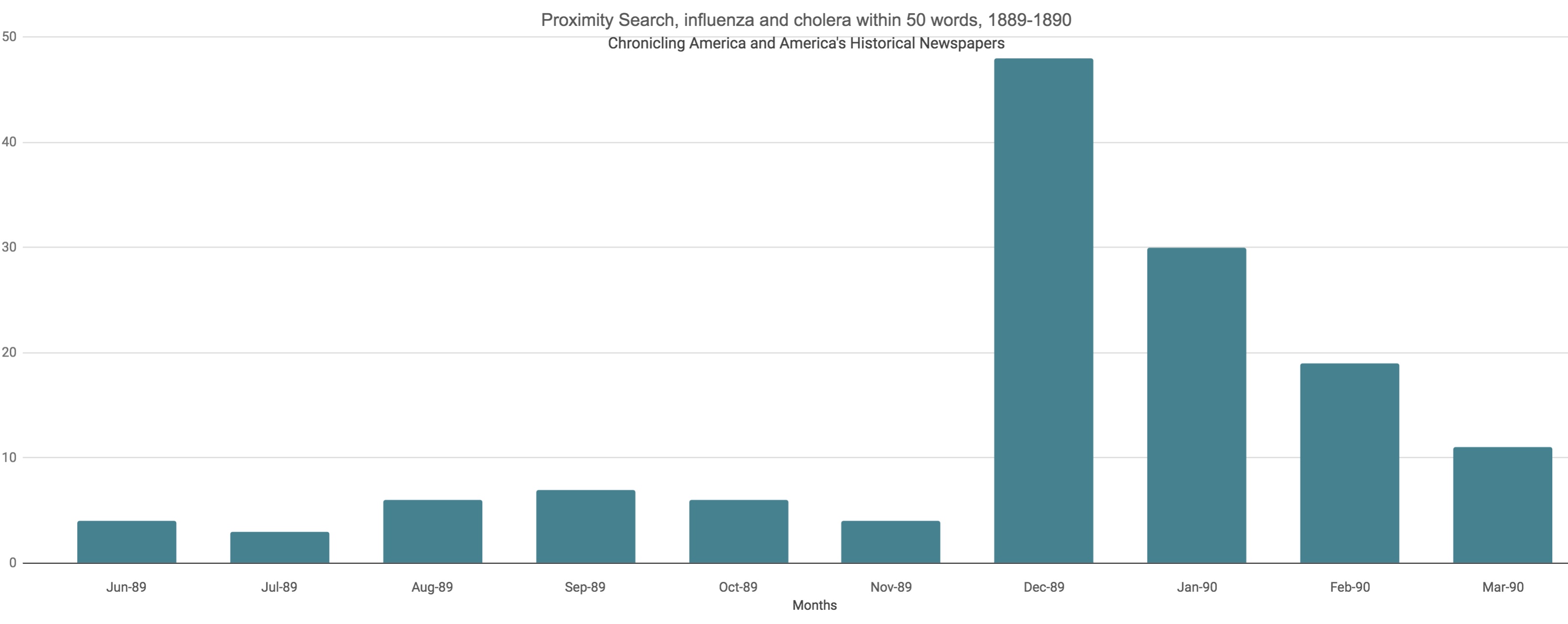

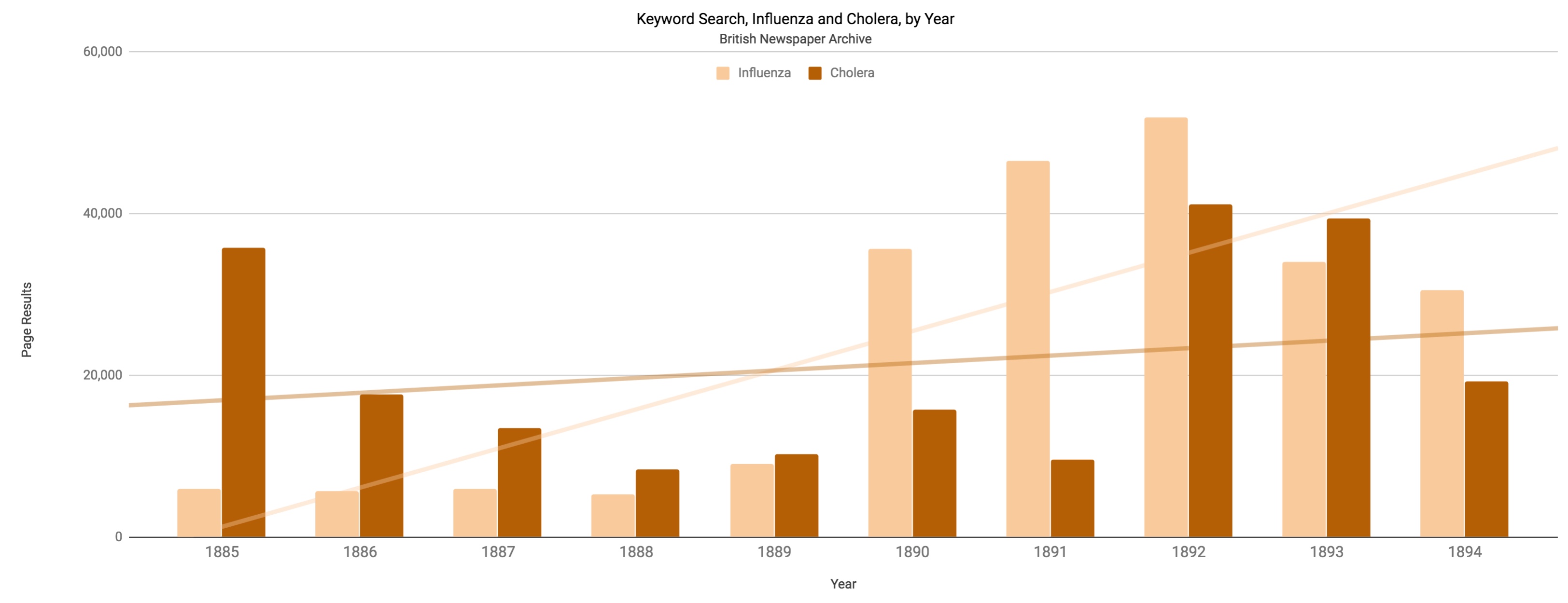

Tracking term frequency in digitized newspaper collections (see figures 1–4) clearly indicates how Zdekauer’s statement changed reporting on the relationship between these two diseases. Whereas the two terms rarely appeared in the same sentence, paragraph, or phrase prior to December 1889, suggesting the two diseases were not seen as connected, the impact of Zdekauer’s statement and subsequent responses could be seen in the marked increase in results of proximity searches across newspaper titles. Keyword searches can document continuity and change, two key issues for historical scholarship, but they do not reveal meaning or demonstrate causation. Close reading reveals that many newspapers and medical journals actually challenged Zdekauer’s statement. On December 3, 1889, The Times of London offered a sweeping denial of remarks that the same newspaper had reported one day earlier:

The suggestion, however, which has been attributed to Professor Zdeckauer [sic], to the effect that the epidemic now existing in Russia is probably premonitory of cholera in the spring, is one which appears to derive no support from either reason or experience. The two diseases are totally unlike one another, and probably the only recorded coincidence between them, even in point of time, is that, as already mentioned, influenza followed soon after cholera in the country in 1833.

This challenge was articulated in a most authoritative way by the British Medical Journal on December 7, 1889: “The theory which has again been given currency in the telegrams from St. Petersburg that epidemic influenza is a forerunner of cholera need only be mentioned in order that it may be condemned as utterly unfounded.” While influenza and cholera epidemics may occur in chronological proximity, the pattern “has abundantly proved that there is no kind of causal connection.”8 In the United States, the Medical Record offered an equally sweeping statement in a front-page editorial on December 14, 1889:

We observe that some feeling of alarm prevails lest this epidemic be a precursor to cholera, as was the case in 1831 and 1847. There have been, however, plenty of cholera epidemics without a preceding influenza, and a great many influenza epidemics without any associate cholera. The micro-organisms of the two diseases are as essentially different as are the diseases themselves. The cholera germ lives in water and soil, the influenza germ in the air. The relationship between the two diseases has been, we believe, purely accidental.9

Newspapers also cited the opinions of doctors, either individually in interviews10 or as the collective view of the profession, as in this New Haven Register article on December 14, 1889:

One reason why this disease is dreaded is because it is thought by many to be a sure forerunner of Asiatic cholera. This is based upon the fact that some previous outbreaks of this sort have been followed by the dread visitation of cholera. The best physicians are not entirely agreed upon the subject, but perhaps the balance of opinion is in favor of the belief that the two diseases are in no way connected. We have no more reason to fear an outbreak of the cholera now than ever before.

This statement, “the two diseases are in no way connected” acknowledges the difference between causation and correlation: doctors agreed that the two diseases were not causally connected, in the sense that influenza could not cause cholera nor were the causes of the two diseases at all similar. As this review of evidence clearly suggests, however, the two diseases were connected because they were part of the medical imagination of the era and thus appeared in proximity to each other in newspapers, journals, and doctors’ public statements.11

Zdekauer was aware of how his statement had been misinterpreted and tried to correct the record. On December 3 (15), 1889, the Russian newspaper Novoe Vremia published his letter claiming that his remarks “had been misrepresented in the press.” Zdekauer denied that he had claimed any organic connection between the two diseases, but he affirmed instead the goal of raising concerns about cholera with the intention of prompting the Society and government to implement sanitary measures, which were described in some detail in the rest of the letter.12 Through this public appeal, Zdekauer engaged with debates prompted by misinterpretations of his comments which had been reproduced, questioned, and repudiated on a global scale.

This study of reports about causal relationships between influenza and cholera builds upon, but also challenges, the analysis of viral texts published by Ryan Cordell in an influential article in American Literary History.13 Drawing on the materials and methods associated with the Viral Texts digital humanities project, Cordell makes extensive use of digitized newspapers to explore the “networks of information exchange” created, sustained, and broadened by selection and republication of texts. Cordell introduces the concept of “network author” to illustrate “the ways in which meaning and authority accrued to acts of circulation and aggregation” across mid-nineteenth century American newspapers. Using Cordell’s analytical framework suggests that references to cholera and influenza were “textual clusters,” similar to those identified by the Viral Texts algorithm, but in this case, identified through proximity searches across databases. Brief news reports from St. Petersburg, warnings about possible cholera outbreaks, and repudiation by medical experts of these warnings were examples of textual exchange that linked mass circulation newspapers, medical periodicals, and individual doctors and researchers as “information brokers,” again using Cordell’s suggestive terminology. An analysis of the complex relationship between cholera and influenza requires, as suggested by Cordell’s research, an appreciation of the potential of the digitized archive to suggest connections in ways that can transform interdisciplinary research.

This study also confirms the arguments of Christopher Hamlin’s Cholera. The Biography about the distinctive ways cholera connected expert, political, and popular discourses about health, culture, and community.14 Hamlin’s research is especially productive in its examination of how broad claims about cholera were often based on limited, doubtful, and even non-existent evidence. Newspaper editorials and even doctors made frightening predictions of future cholera outbreaks based on repeated reporting about a single, mostly misunderstood, statement from a Russian physician, just as Hamlin’s examples show that most published reports about cholera perpetuated a simplified version of the disease that served rhetorical purposes yet were often far removed from medical analysis.

Focusing on the discussion of whether influenza was causally related to cholera is a way to understand how researchers understood etiology in 1889, how knowledge circulated between expert and public audiences, and how information was disseminated globally, regionally, and locally. A doctor’s public statements, a wire service report published in newspapers, and editorials in medical journals are representations to be examined as a way to understand these broader processes. Whereas recent scholarship in digital humanities has suggested new and potentially transformative arguments for the value of network analysis for understanding authorship and readership, this study argues that historians need to go further to ask how practices of republication also contained elements of validation, correction, and even repudiation. Research on the circulation of medical knowledge requires more than the identification of clusters in order to understand how the public, newspapers, and medical experts made sense of a new threat to public health and sought to communicate this understanding to expert and public audiences. This study also contributes to new perspectives in digital history by examining a situation where a Russian scholar participated in the scientific debate—not as an exotic representative of the Other, but as a highly qualified expert—whose expertise made it worthwhile to offer a reasoned critique.

In spring 1892, just two years later, a devastating cholera epidemic struck Russia, causing more than 250,000 deaths, and prompting health officials to acknowledge that unsanitary living conditions, particularly lack of clean water, contributed to high case and death rates.15 In other words, the 1892 cholera outbreak validated demands for preventive measures raised by Zdekauer during the 1889 influenza outbreak. In fact, following Zdekauer’s death in early 1897, the British Medical Journal, which had adamantly denounced any connection between influenza and cholera, offered a belated concession: “It will be remembered that when influenza appeared in Russia in the autumn of 1889, Zdekauer was strongly of the opinion that an epidemic of cholera might be expected to follow, a view which was justified by subsequent events.”16

For historians, understanding the significance of Zdekauer’s statement requires both the large scale searching and sorting available from digitized collections and the close reading and contextual interpretation necessary for critical analysis. While the sensationalist nature of the popular press as well as the scientific concerns of the medical press combined to bring global attention to a remark made at one meeting in St. Petersburg, these same sources also enable the historian to interpret the purpose and meaning of these remarks in their context. Tracing the reporting on Zdekauer’s statement reveals how quickly misinformation could be transmitted on a global scale at a time of heightened concern about the threat of widespread disease. Yet these same sources, including newspapers and medical journals, also demonstrate how quickly both the leading authorities in medical science and publications aimed at public audiences questioned these reports and presented authoritative alternatives based on reasoned analysis. Affirming the dissimilarity of influenza and cholera also served to affirm the value of a public sphere which allowed for measured discussion, thoughtful intervention, and the articulation of an emerging scientific consensus about disease etiology.

Bibliography

Bresalier, Michael. “‘A Most Protean Disease’: Aligning Medical Knowledge of Modern Influenza, 1890–1914.” Medical History 56, no. 4 (2012): 481–510.

British Newspaper Archive. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/.

Chronicling America. Historic American Newspapers from the Library of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/.

Clemow, Frank. The Cholera Epidemic of 1892 in the Russian Empire. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1893.

Cordell, Ryan, and David A. Smith. “Reprinting, Circulation, and the Network Author in Antebellum Newspapers.” American Literary History 27, no. 3 (2015): 417–445.

“Epidemic Influenza.” British Medical Journal 2, no. 1521, (December 7, 1889): 1290–1291. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2155969/

“Epidemic Influenza.” The Medical Record 36, no. 24, (December 14, 1889): 661. https://archive.org/stream/medicalrecord06conggoog#page/n671/mode/2up.

Ewing, E. Thomas. “‘Will It Come Here?’ Using Digital Humanities Tools to Explore Medical Understanding during the Russian Flu Epidemic, 1889–90,” Medical History 61, no, 3 (July 2017): 474–477.

Ewing, E. Thomas, Sinclair Ewing-Nelson, and Veronica Kimmerly. “Dr. Shrady Says: The 1890 Russian Influenza as a Case Study for Understanding Epidemics in History.” Medical Heritage Library Research Blog, August 2016, http://www.medicalheritage.org/2016/08/29/dr-shrady-says-the-1890-russian-influenza-as-a-case-study-for-understanding-epidemics-in-history/.

Ewing, E. Thomas, Veronica Kimmerly and Sinclair Ewing-Nelson. “‘Look Out for La Grippe’: Using Digital Humanities Tools to Interpret Information Dissemination during the Russian Flu, 1889–1890.” Medical History 60, no. 1 (January 2016): 129–131.

Frieden, Nancy. “The Russian Cholera Epidemic, 1892–1893, and Medical Professionalization.” Journal of Social History 10, no. 4 (1977): 538–559.

Hamlin, Christopher. Cholera. The Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Honigsbaum, Mark. A History of the Great Influenza Pandemics. Death, Panic, and Hysteria, 1830–1920. London: I. B. Tauris, 2014.

Mussell, James. “Pandemic in print: the spread of influenza in the Fin de Siècle.” Endeavour 31, no. 1 (March 2007): 12–17.

“St. Petersburg. Death of Professor Zdekauer.” British Medical Journal, 1, no. 1885, (February 13, 1897): 428. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2432980/?page=3.

Notes

Funding for this project was provided by a bilateral digital humanities grant, Tracking the Russian Flu, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and from the Department of History at Virginia Tech. In its initial stages, the project benefited from collaborations with undergraduate research assistants Veronica Kimmerly and Sinclair Ewing-Nelson. Earlier versions of this draft received productive comments from Jeffrey Reznick, PhD, and participants at the 2015 American Association for the History of Medicine Annual Meeting.

-

The same comments from Dr. Albert Robin also appeared in the Omaha Daily Bee, December 15, 1889, 1; Evening Star (Washington DC), December 17, 1889, 1; ten days later, in the Iowa County Democrat, December 27, 1889, 1; and another week later, in the Wood County Reporter, January 2, 1890, 5. ↩

-

This article was located with a proximity search tool that found approximately fifty pages in the Library of Congress Chronicling America database with the terms “influenza” and “cholera” within 50 words of each other during December 1889, the month when the Russian influenza first attracted global newspaper coverage. More results can be found by accessing commercial databases, including Proquest Historical Newspapers, America’s Historical Newspapers, and newspapers.com, although the overlap between these collections complicates efforts to quantify and compare results. This search function is much more efficient than reading through thousands of newspaper pages to find articles that may have addressed the connection between these two diseases. In fact, nearly all of the results from this search technique were articles, editorials, or other reports about the possible relationship between these two diseases, with just a few examples that did not make this connection. The fifty pages with both terms in proximity marked just 6% of the nearly 900 pages with the term influenza during this same time period in the same digitized collection. Yet knowing how to set up the proximity search using the right keywords and data parameters depends on an understanding of the distinctive historical context as well as the identification of the right questions. ↩

-

Bresalier, “‘A Most Protean Disease’ 481–510; Honigsbaum, A History of the Great Influenza Pandemics; Mussell, “Pandemic in print,” 12–17; Ewing, Kimmerly and Ewing-Nelson, “‘Look Out for La Grippe’,” 129–131; Ewing, “‘Will It Come Here?’,” 474–477. ↩

-

Novoe Vremia, November 18 (30), 1889, 3. Nikolai Fedorovich Zdekauer was born in 1815, entered the medical faculty at St. Petersburg University in 1831, and became a professor after completing his Doctor of Medicine degree in 1842. In the 1860s, he led Russian efforts to investigate the cholera outbreak, which led to recommendations to implement sanitary measures. In 1878, he became the first present of the first Russian National Health Society, he was appointed a foreign honorary member of the Epidemiological Society of London, and he served as family physician to Tsar Alexander II. He remained active in medical societies until his death in 1897. Biographical information comes from the obituary published in the British Medical Journal, “St. Petersburg. Death of Pofessor Zdekauer,” 428, as well as the detailed entry in the Russian Wikipedia: Здекауер, Николай Фёдорович, Материал из Википедии — свободной энциклопедии. As will be seen in this chapter, the name Здекауеръ was printed in many different spelling variations, which further complicates the use of text search tools to trace the spread of these reports. ↩

-

The difference with the Russian calendar was 12 days, so the conference was November 17 (29), 1889. Russian newspapers included both dates on their front page. An article published on November 19 (30), in the Moscow newspaper, Moskovskie vedomosti, offered a mostly similar report about Zdekauer’s statement—but made no mention of the claim that the influenza microbe could develop into cholera. ↩

-

London Evening Standard, December 2, 1889, 5. ↩

-

Similar reports, with various spellings of the doctor’s name, appeared on Los Angeles Daily Herald, December 2, 1889, 7 (Zoeker); St. Paul Daily Globe, 4 (Zdenecker); Omaha Daily Bee, 3; Deseret Evening News, 4 (Zedsaner); Indianapolis Journal, 1; Waterbury Evening Democrat, 4; and The Sun, 2 (all spelled Zdekaner). ↩

-

“Epidemic Influenza,” British Medical Journal, 1290–1291. ↩

-

“Epidemic Influenza,” Medical Record, 661. Further amplifying this dismissal, Dr. Shrady, editor of the Medical Record, was quoted in an interview published in the Evening World, on December 13, 1889: “Dr. Shrady recalls epidemics of influenza in 1847 and 1866, but each time followed by cholera, but he says: “That was a coincidence, I think. I do not think there was any connection between the two, and I apprehend no trouble to New York from cholera now. The city is too well fortified against cholera.” Evening World, December 13, 1889, 1. For more on Dr. Shrady’s significance during the Russian influenza, see Ewing, Ewing-Nelson, and Kimmerly, “Dr. Shrady Says.” Similar dismissals were voiced by medical experts both nationally and regionally in the days that followed. On December 14, 1889, the Salt Lake Herald published an interview with Dr. Louis Sayer, another New York physician with a national reputation, who similarly drew upon his memories of recent outbreaks to clearly differentiate between the two diseases: “My advice is that when it comes don’t get scared. Trust to Providence and keep you powder dry, as it were, by keeping up courage while you relieve your misery and preserve your strength as much as possible. Go slow, take it easy, take good care of yourself, and you will have done all you can to lessen the misery. From influenza, or its subsequent results, the suggestion that it is liable to be followed by cholera is nonsense. I anchored cholera in the bay when it visited this country last, and it can be kept out without any trouble.” Salt Lake Herald, December 14, 1889, 1. ↩

-

In a Pittsburg Dispatch article published December 17, 1889, Dr. William Pepper from the University of Pennsylvania reviewed the symptoms of influenza, and ended with this summary statement: “There is, therefore, no ground whatever for alarm about a possible outbreak of cholera. The two diseases have nothing whatever in common, and the intestinal type of influenza does not present any greater danger than the resperator type.” Pittsburg Dispatch, December 17, 1889, 1. ↩

-

One interesting feature of this discussion, however, was the tendency to suggest that the public continued to believe in a connection between these diseases, despite the repeated affirmations of medical experts. The New York Times on December 10, 1889 warned: “It is the popular belief in Europe that the present epidemic of influenza is the forerunner of an epidemic of Asiatic cholera…While there is no direct connection between the influenza epidemic and a visitation of the cholera, there is at the present time great danger of the appearance of cholera in Europe, because it is already prevailing in the region just east of the eastern extremity of the Mediterranean.” The New York Times, December 10, 1889, 4. Yet newspapers themselves contributed to the persistence of these claims. On December 28, 1889, the Pittsburg Dispatch published an editorial that repeated the claims attributed to Dr. Zdekauer almost a full month after his comments had been widely repudiated by newspapers, journals, and doctors: “One of the most unpleasant suggestions in regard to the influenza epidemic is that it is in some way connected with cholera, and is frequently a forerunner of it. A skillful Russian specialist on both diseases, Prof. Zehekaner [sic], favors this view. But his argument and those of his followers only prove that certain atmospheric conditions favor both diseases. We of this latitude have a liking for a cold winter, and if it is needed to keep cholera away from us next summer our prayer is for frost and lots of it.” Pittsburg Dispatch, December 28, 1889, 4. Some newspaper reports attempted tried to explain why this erroneous belief persisted—even among members of the medical profession, as in this analytical article in the Pittsburg Dispatch on January 5, 1890. After stating that influenza “runs across the country from southeast to northwest, as cholera does,” the article stated that influenza often moved against the prevailing air currents yet could travel quite far in a short period of time, leading to this broad analytical statement: “This remarkable faculty it has of traveling so rapidly as against the general course of the air makes it resemble cholera, and from the fact that it has on two occasions been followed during the next summer by cholera, some wise physicians have had an idea that it might be followed by the same disease next summer. It follows no more than smallpox follows whooping cough.” Pittsburg Dispatch, January 5, 1890, 16. ↩

-

Novoe Vremia, December 3 (15), 1889, 3. ↩

-

Cordell and Smith, “Reprinting, Circulation, and the Network,” 417–445. ↩

-

Hamlin, Cholera. The Biography. ↩

-

Clemow, Cholera Epidemic of 1892. The cholera outbreak prompted Russian physicians to take an increasingly active, visible, and public role in advocating for effective measures such as improved sanitation, consistent quarantines, and health education. Frieden, “Russian Cholera Epidemic, 1892–1893.” 538–559. ↩

-

“St. Petersburg. Death of Professor Zdekauer,” 428. ↩

Appendix

Author

E. Thomas Ewing,

Department of History, Virginia Tech, etewing@vt.edu,