Growing Strong

The Institutional Expansion of Knowledge in the Early Republic

Abstract

It is often enticing to see the proliferation of knowledge and knowledge creating institutions, such as professional societies, as evidence of an expansion and democratization of information in the early republic. However, as specialized interests flourished, and the membership in specialist organizations increased, it is reasonable to ask did the opportunity for collaborative interactions between different groups of people decrease instead of increase? In other words, did the increase in the number and variety of societies promote expansion of heterogeneous interests rather than binding groups together through singular designs that promoted national interests? Typically, scholars examine one group, or set of groups at a time. As such, historians of science frame their understanding within the context of scientific discourse while historians of agricultural institutions, or religion, or politics each focus on their own niche. Therefore, examining the makeup of multiple institutions across disciplinary barriers offers an opportunity to explore a larger proportion of the community in the early American republic.1

Examining multiple institutions is difficult due to the breadth of the scope of material that historians need to engage to glean insights into those institutions. Visualization strategies are useful for providing refined questions for further research and may be illustrative of patterns which would otherwise be undetected due to scattered archival materials in different institutions. Further, they offer significant opportunities for scholars to find new uses for old sources. These sources have been sitting on shelves, in boxes, or sometimes are available online, however they have been unusable due to the limited ability of people to draw the thousands of connections between the hundreds of organizations. Using computational methods helps scholars provide more nuance to their questions and answer questions that could not be addressed earlier, thereby enhancing our understanding of the past. A careful examination of a corpus can offer a “medium reading” of sources which consist of a “large but narrowly constrained corpus centered on solving a well-defined research question.”2 Through the exploration of social networks of the members of learned societies between 1790–1860 using their membership lists, and those of other learned groups in civil society, we can explore the nature of the creation and dissemination of information in the first half of the nineteenth century.

The social network graph included herein is a part of an ongoing project to compare shared memberships between the different groups during the first half century of the early republic. The list currently consists of 7,745 names and 17 organizations. Selection of these groups started by identifying the oldest learned societies in the republic and then adding many of the specialized institutions such as the East India Marine Society and the Academy of Natural Sciences. These were typically selected due to their early establishment and due to the complete nature of their membership lists. Many records of these organizations survived probably due to the advantage of having a large number of leading citizens of the republic on their rolls. The records of other important groups are inconsistent and limited numbers have survived, as is the case with the Medical Society of the District of Columbia, yet their inclusion was important due to their specialized purpose and their location in the federal city. Occasionally organizations such as the Columbian Agricultural Society published the names of their membership in their journals or other proceedings. Finally, adding in federal employees and Army officers during strategic dates offered opportunities to explore if there was a change from a homogenous information environment to a more diverse and specialized republic of letters.3

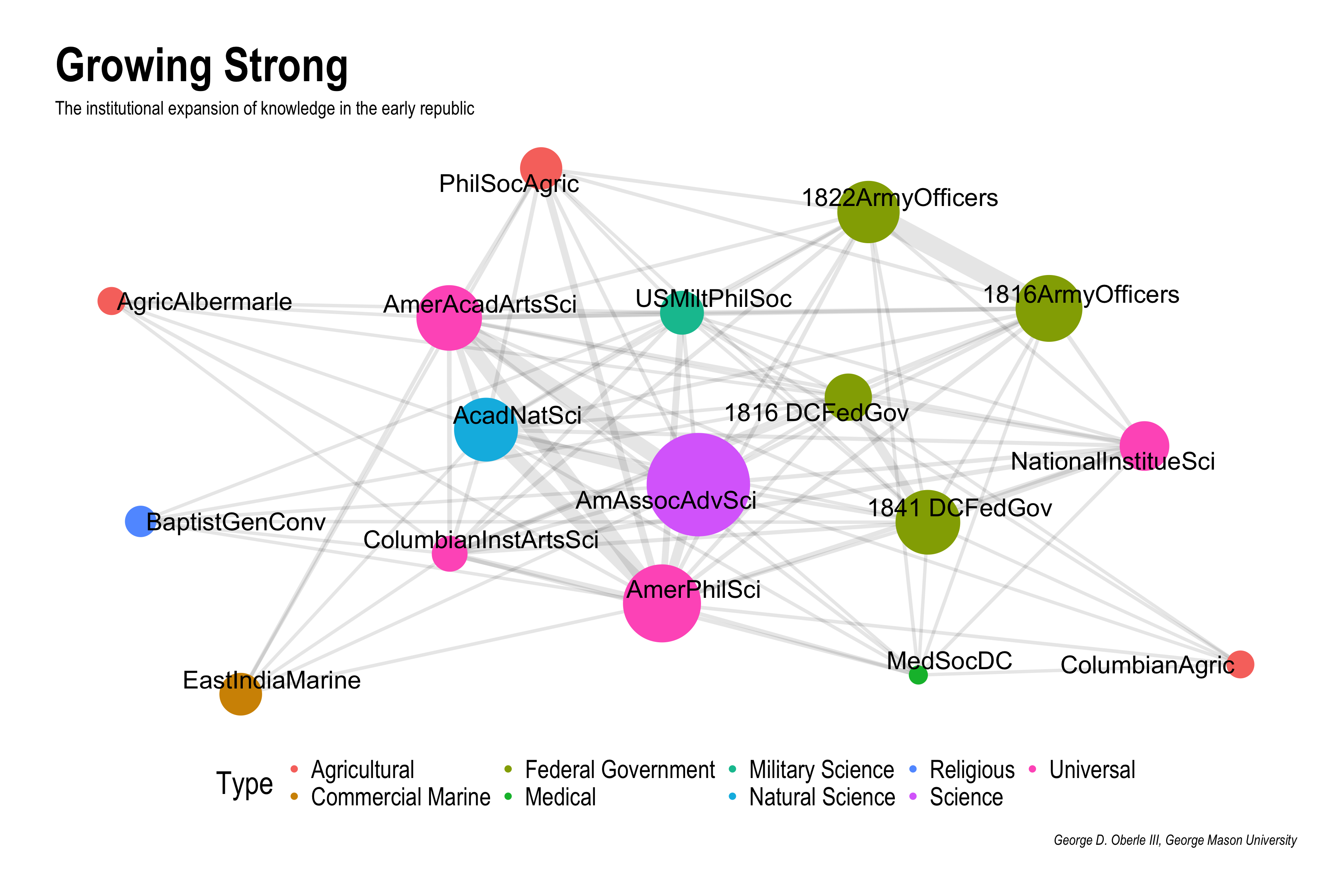

Using software constructs a visualization where the thickness of the edges indicates more connections between different institutions. This network graph also provides a visualization of the size of each organization represented in the list based on the total number of members.4 For example, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AmAssocAdvSci) is obviously the largest single group in the graph, while the Medical Society of the District of Columbia is the smallest based upon the relative sizes of the circles. This helps distinguish the relative size of the groups. Coloring the nodes of organizations by type of group also offers an opportunity to show the diversity and expansive nature and variation of interests in civil society. The thickness of the adjoining lines indicates more shared memberships between groups. Clearly, figure 1 shows a significant level of connections between individuals across different groups and suggests that a complex web of relationships existed between these diverse set of elites across the republic.

Despite the fact that the learned citizens of the republic seem connected through shared memberships across time, even between small organizations, this data offers interesting observations which suggest that very few people actually shared large numbers of connections. For example, there were only thirty-six occurrences of shared memberships which consisted of five shared organizations or more. James Bowdoin and John Pickering made-up twenty-two of the thirty-six. They also shared the most shared memberships with ten. What stands out from this smaller list of links is that there are fewer shared memberships between people who lived in the antebellum period. Those belonging to five or more groups who lived into the antebellum period were John Quincy Adams, John P. Jones, and Benjamin Silliman. This may indicate that as specialized groups emerged many of the white learned men, represented in this graph, were unable or unwilling to belong to multiple groups.

The diversity of groups in the graph can be observed in the assignment of type indicated by different colors in the graph. The primary purpose of organizations offers a useful way to visualize the diversity of types of organizations in this period. Using the federal government as a category offers an opportunity to explore connections between societies across the republic. In the case of the U.S. Army officers we can see beyond the regional bias which many exist from the organizations, which are mostly based in New England and the Mid-Atlantic region. These officers were scattered throughout the country. Additionally, using the federal employees that worked in the District of Columbia can offer insights into the impact of the federal city as a metropole for the nation.5 Additionally, this visualization can help demonstrate the diversity in the exploration of knowledge away from learned societies which focused on universal aspects of knowledge, such as the American Philosophical Society and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, to more specialized groups. The diversity of this environment became crystalized in the proliferation of civil societies in the early republic and also in the expansion of democracy in the Jacksonian period. The proliferation of civil societies in the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century converged with the expansion of publishing, which provided opportunities for many of these organizations to widely disseminate their message to a diverse public. The common belief among many Americans was that a vibrant civil society offered the best means to diffuse knowledge to the populace. This is a significant change from the early republic which greatly feared factions. This freedom within the public sphere offered opportunities for many citizens to expand their knowledge beyond the education acquired in their formative years. Members viewed these groups as an important defense against tyrannical government and as a way to defend liberty. Establishing and joining groups formed a crucial part of the democratic experience. Alexander de Tocqueville famously observed, “Americans of all ages, of all conditions, of all minds, constantly unite.”6 They did this on a scale and scope that was surprising to Tocqueville, yet he found these societies necessary to a democratic society. People joined all kinds of societies including scientific societies and proto-professional societies. These were a crucial part of the development of the expanding capacity for commercial growth in the United States. Members joined because they imagined they were participating in a project which was advancing American civilization through moral improvement and by learning. The craving for new scientific wonders and knowledge gripped the populace as more people participated in manufacturing, engineering, mining, and an ever more rationalized agricultural system.7

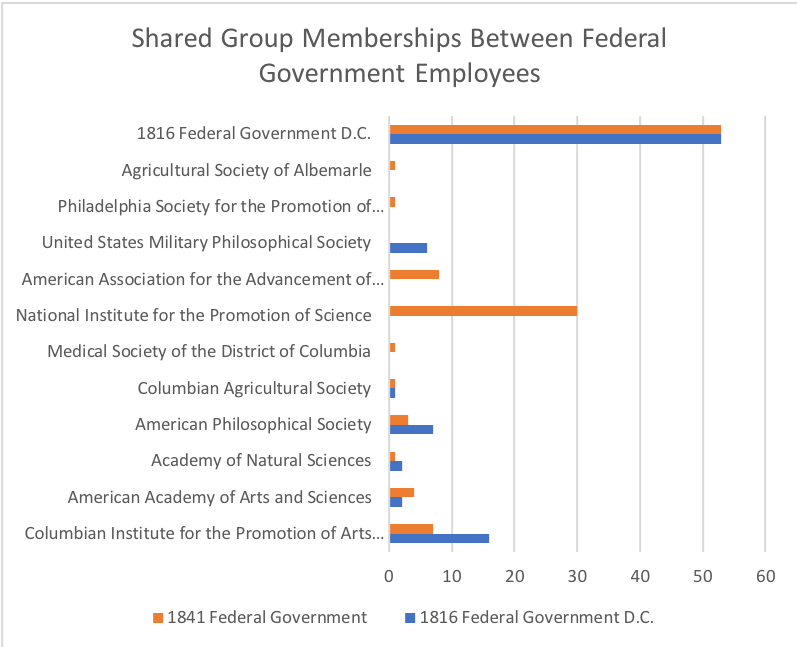

Some of the most interesting relationships in this graph are the federal employees who lived in the Washington D.C. Figure 2 breaks out the network relationships into numerical values. Despite the span of twenty-five years between 1816–1841 and the drastic political changeover in the cabinet and elected government there were fifty-three people that remained employed by the government in the national capital. This constitutes the most shared relationships in the chart with only the D.C. based National Institute for the Promotion of Science (National Institute) coming close with thirty shared memberships. In 1816 there were only two hundred sixty-four federal employees in Washington and this increased approximately forty-two percent in those twenty-five years so that by 1841 there were six hundred twenty-nine. The fifty-three people that remained represent eight percent of the total number of employees in 1841. Additionally, the graph shows us an interesting challenge with examining these types of groups. Groups start and end. When examining figure 2 we can see that the National Institute has no shared members in 1816 because it was not formed at this point in time. The Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences was its predecessor, yet it had only sixteen shared memberships with the 1816 Federal government and was technically still in existence in 1841, despite the move of most of the members to the new National Institute. The proliferation of shared memberships in learned societies does not seem to be associated with employment in the federal government at this point in time. This may suggest that the traditional notion that the expansion of the federal government led to an expansion in scientific learning may not be as interconnected in the early nineteenth century as it is in the twentieth.8

So, although more people were joining societies it remains unclear if there were significant numbers of connections between groups. The democratic impulse which is evident from the expansion of white male voting rights and expansion of the marketplace between 1820–1850 also offered an expansion of the chaotic knowledge production environment.9 Ironically the expanding democratic view of knowledge, which offered opportunities for non-elite citizen scientists to collect, codify, and even explain objects within the world in which they lived, added to the sense of disarray amongst the populace due to the multitude of conflicting messages from an overwhelming number of sources. Localized learned societies offered individuals the opportunity to practice their work with like-minded colleagues and neighbors. As the opportunities to participate in scientific activities by average citizens expanded many scientists longed for greater disciplinary specialization and scholarly rigor. Some called for a nation-wide organization, such as the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the National Institute as well as other specialized national associations, such as the United States Agricultural Society. Each group focused on their own disciplinary interests which they believed would promote and expand knowledge for the good of all. These new national institutions, mostly specialized, also offered a mechanism to assure credibility to scientific discourse in the United States.

The establishment of groups such as the American Academy for the Advancement of Science led to, what one scholar called, a “level of maturity” for American society to develop an important combined voice to enhance scientific progress. These groups also marked a change from the older organizations which emphasized the universal nature of knowledge to a more specialized version. This led the new professional type of scientist with a key goal: the separation of political interests from science. The universal organizations of knowledge represented in pink in figure 1 were starting to become less important. The National Institute, the last of these major universal organizations, was successful in building political relationships with federal employees yet they were not able to connect with the increasingly specialized scientific societies. For example, the National Institute and the AAAS only shared nine members while the National Institute and the American Philosophical Society, the oldest learned society in the US, shared thirteen connections. What makes this more interesting is that the AAAS and the National Institute were both nationally focused organizations which were based in Washington D.C. It seems as if many from the AAAS believed that only a clear focus on science scholarship would allow these organizations to shed partisanship in order to guide scientific policy for the nation.10 In their view there were too many unqualified participants in scientific endeavors. One example includes Joseph Henry, professor of Natural Science at the College of New Jersey (and future Smithsonian Secretary), who complained that journal editors across the country were providing a platform for scholars to share their dubious claims when exposing the false claim that electrification could be utilized to fertilize insect eggs which were in water drops. Henry confided in a letter written on August 9, 1838 to his friend and fellow scientist Alexander Dallas Bache his disappointment with the nation’s premier scientist, Benjamin Silliman, the founder of the American Journal of Science for not having enough reviewers of the content published in his journal. Henry reminded Bache of their goal: “we must put down quackery or quackery will put down science.”11 Since scientific learning needed to become apolitical, and thus not subject to the egalitarian inclination in society, those that saw themselves as serious scholars longed for the establishment of systematic processes for analysis to thwart the proliferation of charlatans and the misinformation they propagated among the uneducated. The assumption is that the new group offered a separation from the chaos of the political realm. Like in an earlier period the world of scientific truth had no place for controversy. The politics of citizens and the state became a new expression of the distrust caused by discord between different groups.

The proliferation of science and scientific organizations did not always promote national progress. Scholars have detected ideological distinctions that fundamentally differentiated the scientific pursuits of scholars who were Federalists from those who were Jeffersonian-Republicans. These ideological divisions led to a deep and intense level of skepticism by Federalists of the validity of what they called disparagingly “Jeffersonian Science.” Federalists resented many of these questionable areas of study and viewed the practitioners as pretenders who claimed a scientific authority that the Federalists deemed undeserved. The tension between groups such as this might offer an opportunity for a competition of advancement in which a marketplace of ideas can develop new types of knowledge and advancements. This could also could create a desire for authority and a desire for homogeneity. This fear continued into the antebellum period and by 1826 Benjamin Silliman, was eager to differentiate between those that he viewed as savants and those that were true scientists. He counted at least 28 societies in the country spread across ten states and the District of Columbia. Of the twenty-eight reported, two-thirds were located in the three states of New York (11), Pennsylvania (4), and Massachusetts (4).12 Also, twenty-four of them were specialized scientific societies, or lyceums, promoting scientific topics and only four were universal institutions that resembled the American Philosophical Society. This move toward professionalization and popular infatuation with science became a national trend until the Civil War.13

Even though these numbers are impressive they pale when compared to other proto-professional societies and fraternal societies which Silliman filtered out from his census of scientific societies. For example, among the most expansive were the estimated more than nine hundred agricultural societies founded across the United States before the Civil War. Many states had even established state boards of agriculture and, like with many organizations, there were some that called for a national institution to join together the disparate groups. Since many of these states did not adequately fund their state boards and institutions they called for the establishment of the United States Agricultural Society (USAS).14 The USAS, established in 1852, both attempted to unite the estimated over nine hundred agricultural society groups across the republic under a single umbrella and sought for federal funding of the work to promote agriculture. The society, headquartered in Washington D.C., included “a Free Agricultural Library at the National Metropolis” in which publications and specimens of seeds, engravings of animals, as well as models of agricultural implements from various societies across the country, were collected. Here they also held meetings in the newly established Smithsonian Institute, published a quarterly journal, and organized annual national agricultural exhibition fairs at cities across the country such as Springfield Massachusetts, Springfield Ohio, Boston, Philadelphia, Louisville, Richmond, and Chicago. The group promoted the display of a host of the finest agricultural specimens, mechanical implements, domestic productions, and even artistic and scientific productions by offering twenty thousand dollars in premiums to participants.15 From the inception of the USAS their members called for a federal department of agriculture, which infuriated many southern agricultural advocates who saw this move as both inappropriate and unnecessary. Edmund Ruffin, a leader in agricultural knowledge, promoter of southern agricultural societies, and ultimately a fire-eating secessionist had, at best, mixed feelings about the society in 1858. He refused to join the society because he opposed the attempts to draw support from the federal government while still supporting their objective to promote agricultural knowledge and because he saw the organization as a political arm of antislavery interests. At times he even felt “conscious-struck for my general dislike to all Yankees” yet this did not change his distrust of them.16 Ruffin was a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Society which was a national institution that many judged at the time to be an apolitical organization.

In the end, network graphs can help us visualize many relationships and, if used alongside traditional sources, they can offer a richer understanding of the past. Figure 1 shows that very diverse groups often have shared memberships that one would not necessarily expect. Still, there are many limitations to the graph. Although this graph shows that many people were connected in many diverse groups in many cases only a few people had multiple memberships. Using the names of these key individuals we can explore their roles in the organizations and see if they had a significant impact in sharing knowledge to a diverse community. These key individuals may have been corresponding secretaries. These positions were the main way that the organization communicated with members and other organizations. Identifying these few names we can delve into their papers in a more rigorous fashion. Additionally, there are many more groups which would be useful to add; activist groups such as abolition societies, the American Colonization Society and the American Temperance Society come to mind. Also, there are many silences due to the fact that the source pool remains vast. These relationships are easy to overlook when examining isolated moments of political turmoil or social disruptions, and we may overlook interdependence and attachments between groups that seem to be distinctive or at odds with each other. The emergence of civil society within the United States remains a vibrant and crucial issue to explore in order to better understand the ties that bind people together as well as those that may tear them apart.

Bibliography

Baatz, Simon. “Philadelphia Patronage: The Institutional Structure of Natural History in the New Republic, 1800–1833.” Journal of the Early Republic 8, no. 2 (July 1, 1988): 111–138. https://doi.org/10.2307/3123808.

Baatz, Simon. “‘Squinting at Silliman’: Scientific Periodicals in the Early American Republic, 1810–1833.” Isis 82, no. 2 (June 1, 1991): 223–244.

Carrier, Lyman. “The United States Agricultural Society, 1852–1860: Its Relation to the Origin of the United States Department of Agriculture and the Land Grant Colleges.” Agricultural History 11, no. 4 (1937): 278–288.

Danhof, Clarence H. Change in Agriculture: The Northern United States, 1820–1870. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1969.

Dupree, A. Hunter. “The National Pattern of American Learned Societies, 1769–1863.” In The Pursuit of Knowledge in the Early American Republic: American Scientific and Learned Societies from Colonial Times to the Civil War, edited by Alexandra Oleson and Sanborn C. Brown, 21–32. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976.

Dupree, A. Hunter. Science in the Federal Government, a History of Policies and Activities to 1940. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1957.

Ellsworth, Lucius F. “The Philadelphia Society for the Promotion of Agriculture and Agricultural Reform, 1785–1793.” Agricultural History 42, no. 3 (Summer 1968): 189–199.

Funk, Kellen, and Lincoln A. Mullen. “The Spine of American Law: Digital Text Analysis and U.S. Legal Practice.” The American Historical Review 123, no. 1 (February 1, 2018): 132–164. https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/123.1.132.

Grasso, Christopher. A Speaking Aristocracy: Transforming Public Discourse in Eighteenth-Century Connecticut. Chapel Hill: Published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Virginia, by the University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Gross, Robert A, and Mary Kelley, eds. An Extensive Republic: Print, Culture, and Society in the New Nation, 1790–1840. A History of the Book in America, v. 2. Chapel Hill: Published in association with the American Antiquarian Society by the University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Greene, John C. American Science in the Age of Jefferson. 1st ed. Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1984.

Henry, Joseph. The Papers of Joseph Henry: January 1838-December 1840, The Princeton Years. Edited by Nathan Reingold and Marc Rothenberg. Vol. 4. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, New York, 1981.

Howe, Daniel Walker. The Political Culture of the American Whigs. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979.

Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Kerber, Linda K. Federalists in Dissent; Imagery and Ideology in Jeffersonian America. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1970.

Kohlstedt, Sally. “A Step Toward Scientific Self-Identity in the United States: The Failure of the National Institute, 1844.” ISIS: Journal of the History of Science in Society 62, no. 3 (1971): 339–362.

Kohlstedt, Sally. The Formation of the American Scientific Community: The American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1848–60. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1976.

Mathew, W. M. Edmund Ruffin and the Crisis of Slavery in the Old South: The Failure of Agricultural Reform. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1988.

Neem, Johann N. Creating a Nation of Joiners: Democracy and Civil Society in Early National Massachusetts. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2008.

Oberle III, George, D. “Institutionalizing Knowledge in Washington’s Early Republic.” Panel: Constructing New Lives and Institutions in Antebellum Washington. Washington, D. C. Accessed June 30, 2018. http://mars.gmu.edu/handle/1920/10044.

Oberle, George D. “Institutionalizing the Information Revolution: Debates over Knowledge Institutions in the Early American Republic.” PhD diss., George Mason University, 2016. http://search.proquest.com/docview/1801956690/abstract/FEF47B13049F443DPQ/1.

Oleson, Alexandra, and Sanborn Conner Brown, eds. The Pursuit of Knowledge in the Early American Republic: American Scientific and Learned Societies from Colonial Times to the Civil War. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976.

Rossiter, Margaret W. The Emergence of Agricultural Science: Justus Liebig and the Americans, 1840–1880. Yale Studies in the History of Science and Medicine 9. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975.

Ruffin, Edmund. The Diary of Edmund Ruffin. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1972.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. Democracy in America / Translated, Edited, and with an Introduction by Harvey C. Mansfield and Delba Winthrop. Edited by Harvey Claflin Mansfield and Delba Winthrop. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

United States Agricultural Society. Seventh National Exhibition by the United States Agricultural Society, to Be Held in the City of Chicago, September 12th, 13th, 14th, 15th, 16th, and 17th, 1859. Chicago: Press & Tribune Job Printing Office, 1859. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiuo.ark:/13960/t6542mx0p.

Walther, Eric H. The Fire-Eaters. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

Wilentz, Sean. Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class, 1788–1850. 20th anniversary ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Wilentz, Sean. The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. New York: Norton, 2005.

Notes

This work originated with a seminar class taught by Lincoln Mullen at George Mason University in the Fall semester 2014 called Programming in Digital History/New Media (see http://lincolnmullen.com/courses/clio3.2014) and then was continued in a paper delivered at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the District of Columbia Historical Society deposited in the Mason Archival Repository System, http://hdl.handle.net/1920/10044. I am greatly indebted to Professor Mullen and Jordan Bratt as well as the students in the 2014 class. Dr. Zachary Schrag and Dr. Rosemarie Zagarri both gave me helpful feedback. My friends in George Mason’s Early American Workshop including Jeri Wieringa who provided helpful encouragement and feedback. Finally, I am grateful for the anonymous reviewers and Dr. Stephen Robertson who all graciously provided very helpful insights and suggestions.

-

Oleson and Brown, The Pursuit of Knowledge in the Early American Republic; Dupree, Science in the Federal Government; Oberle III, “Institutionalizing the Information Revolution.” ↩

-

Funk and Mullen, “The Spine of American Law,” 132–164. ↩

-

This began by using the Scholarly Societies project formally hosted at University of Waterloo Library which can now be found at http://www.references.net/societies/. I was very strict at first to only use “learned societies” however it became clear the project could benefit by using other membership lists including members of government employees that worked in the Federal city at different times. Additionally, using Army officers could help explore the idea offered in many works which claim that the Army helped expand scientific knowledge and bind the disparate nation together. ↩

-

The software used was RStudio and the network graph constructed with the package called igraph. ↩

-

Which an earlier study suggests that the organizations in Washington D.C. were relatively isolated from the rest of the republic. See Oberle III., “Institutionalizing Knowledge in Washington’s Early Republic.” ↩

-

Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 489. ↩

-

Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy; Wilentz, Chants Democratic; Howe, The Political Culture of the American Whigs; Howe, What Hath God Wrought; Gross and Kelly, An Extensive Republic; Neem, Creating a Nation of Joiners. ↩

-

Dupree, Science in the Federal Government. ↩

-

Oleson and Brown, The Pursuit of Knowledge in the Early American Republic; Baatz, “Philadelphia Patronage,” 111–138; Kohlstedt, The Formation of the American Scientific Community; These ideas are being developed for a book which is a revision of my dissertation titled “The Institutionalization of Knowledge.” ↩

-

Dupree, Science in the Federal Government, 115–119. ↩

-

Henry, Papers; Oberle, “Institutionalizing the Information Revolution,” 228–231. ↩

-

Oberle, “Institutionalizing the Information Revolution.” ↩

-

Kerber, Federalists in Dissent; Greene, American Science in the Age of Jefferson; here I also rely on the an understanding of the conflict over access to the public sphere by scholars such as Grasso, A Speaking Aristocracy; Dupree, “The National Pattern of American Learned Societies” 21–32. ↩

-

Unfortunately, I have not found a good source for the membership list for the USAS at this time. ↩

-

Carrier, “The United States Agricultural Society, 1852–1860”; Rossiter, The Emergence of Agricultural Science; Danhof, Change in Agriculture; Mathew, Edmund Ruffin and the Crisis of Slavery; Ellsworth, “The Philadelphia Society,” 189–99; United States Agricultural Society, Seventh National Exhibition. ↩

-

Ruffin, The Diary of Edmund Ruffin, 145–146; Walther, The Fire Eaters, 228. ↩

Appendices

Author

George D. Oberle III,

University Libraries and Department of History and Art History, George Mason University, goberle@gmu.edu,