Talk-Back Boards and Text Mining

New Digital Approaches in Museum Visitor Studies

Abstract

Museum visitor studies are in a bit of a rut. This is a statement that should wrinkle foreheads and ruffle feathers, but the reality is virtually all visitor studies projects gather data from visitors in one of three ways: administering a survey scale, organizing focus groups, or observing visitor behavior. Approaches vary and recent work in, for example, Visitor Studies demonstrate a high degree of methodological sophistication, but in reality most designs are hardly different than some of the first visitor studies projects conducted in the 1920s and 1930s.1 However, a simple analog tool—the post-it or sticky note—alongside relatively new digital methods—various text mining approaches—can open up new information about museum visitors. Since the late 1970s, museums have deployed talk-back boards, an interactive exhibit that encourages anonymous public responses to question prompts, as a way to engage visitors.2 A talk-back board is essentially a blank wall or freestanding board with a question printed above in large text. Somewhere within reach, visitors are provided a stack of sticky notes and a few writing utensils.3 Responses are short with an average length of eight to twenty words depending on paper size. Museums informally estimate between 10–25% of all visitors respond to talk-back boards depending on location making the response rate relatively high compared to other methods.4 Digitally exploring talk-back boards provides museums with a new approach with advantages of simplicity, mass data creation, and low cost; the only significant shortcomings are the absence of demographic data collection and that talk-back boards remain a significantly under-researched and under-utilized visitor studies method.

Adding a few new digital tools to a preexisting visitor studies framework provides insight into visitors that no other visitor studies method can capture. Some text mining methods deployed in this analysis include word frequency analysis, co-occurrence mapping, phrase distribution, topic extraction, sentiment analysis, and Regressive Imagery Dictionary (RID) categorization. As for data, the bulk was gathered from Seminary Ridge Museum (SRM) in Gettysburg, PA and Women’s Rights National Historical Park (WORI) in Seneca Falls, NY. The data included in the analysis includes all talk-back responses from SRM over a sixteen-month period spanning 2013 and 2014 (n = 3227) and a random sample of WORI responses created by visitors between 1993 and 2014 (n = 1257). A random sample approach was used for the WORI data because the distribution of data was skewed toward the present as WORI employees did not prioritize gathering talk-back board responses until roughly the past decade.

The primary finding from this study is that talk-back boards offer insight into visitor sensibilities that are often privately held and divorced from the museum setting itself, an insight that compliments the findings of the most common visitor studies methods (surveys, comment books) and duplicates those from much more expensive approaches like focus groups.5 For instance, visitors to SRM shared thoughts on religion that were previously unknown despite the efforts of other visitor studies approaches at the site. Other museums with a religious history theme have reported challenges inferring visitors’ private religious or faith-based thoughts, suggesting talk-back board responses provided information other methods cannot.6 As religious history museums demonstrate, it is especially challenging to engage with the public about religion and museums often have difficulty in understanding what the public wants from their sites. From SRM for instance, a June 2012 survey of repeat Gettysburg visitors administered before the site opened found extremely high interest (99%) in both the opening of a new museum and in events from the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg, but just under 50% of all respondents expressed interest in religion-related topics, the lowest of all items. Some museum staff took this particular survey result to mean that the museum should rethink their approach to incorporate even more Battle of Gettysburg interpretation. However, since SRM’s opening in June 2013, visitation to the site has been healthy and visitors express interest in the religious history presented. Given such a disconnect between survey results and outcomes, the question of how to measure visitor engagement of religious themes at this historic site pestered museum staff.

To address this question, SRM staff installed a talk-back board at the end of the exhibit hall that posed the question “What do you think is the unfinished work for freedom?” Staff noticed immediately that visitors used the talk-back board to reflect upon a range of topics beyond the question's intent though most focused upon politics or religion without any explicit prompting. About 10.7 percent of all respondents directly referenced religion, making “religion” the second most common theme (less than 1 percent behind the most common theme “equality”).7 Difficult topics and complex sensibilities, such as religious belief, consistently emerged from the talk-back board as virtually all respondents couched their responses in such terms. An unexpected result was that very few, less than one percent, referenced the physical museum space itself. This result is in stark contrast to other visitor studies methods, such as museum comment books or surveys, where the inverse ratio is true.8 Further, interactive exhibits research suggested talk-back respondents would directly interact with one another, but just 5.4 percent of all responses clearly interacted via a drawn arrow or reference to a nearby post-it note. Most chose to speak out independently with their own response rather than respond directly to others, which may explain why 10 percent of all respondents provided a signature to publicly claim their talk-back board response.

The critical outcomes of this study at CRM centered on the large quantity of religion-themed responses that did not engage the talk-back question alongside a relatively high proportion of emotion-laden responses. Religiously-minded tourists are a highly diverse group of visitors, so more studies using talk-back boards could discover why so many religious respondents chose not to engage the question and what specific faith-based interests drive tourism to SRM and sites like it. As tourism scholar Amos Ron argued, visitors to religious sites like cathedrals and shrines usually pursue faith-based objectives, but also are in search of culture, cognitive engagement, and/or historical meaning.9 This mixture of spiritual and secular cultural values is apparent in the talk-back board responses, but merit further exploration through the deployment of more talk-back boards. Similarly, the critical role of emotion and restoration at religious sites, SRM included, supports the further use of talk-back boards. Visitors to religious sites generally report stronger emotional connections partially because of faith, but also because of the perceived authenticity of cathedrals, mosques, and other religious sites.10 SRM, the seminary itself, and the surrounding battlefield each possess a special authenticity and thus potential for emotive engagement which can be detected in talk-back board analysis. In comparing SRM with WORI via RID Categorization tests, SRM visitors expressed affection significantly more often in their responses (10.7% v. 5.2%, p < 0.01), WORI visitors more often couched their responses in sensory language, (13.5% v. 6.5%, p < 0.01) and both groups of visitors used a high degree of abstract language (such as “know”, “may”, “thought”, or “understand”). This result suggests that questionnaire-based research is not accurate in some museums as many visitors could view such questioning as intrusive in a religious setting. Rather than interrupting the ambiance of a site many consider sacred, new talk-back questions could tap into such complex questions one piece at a time.

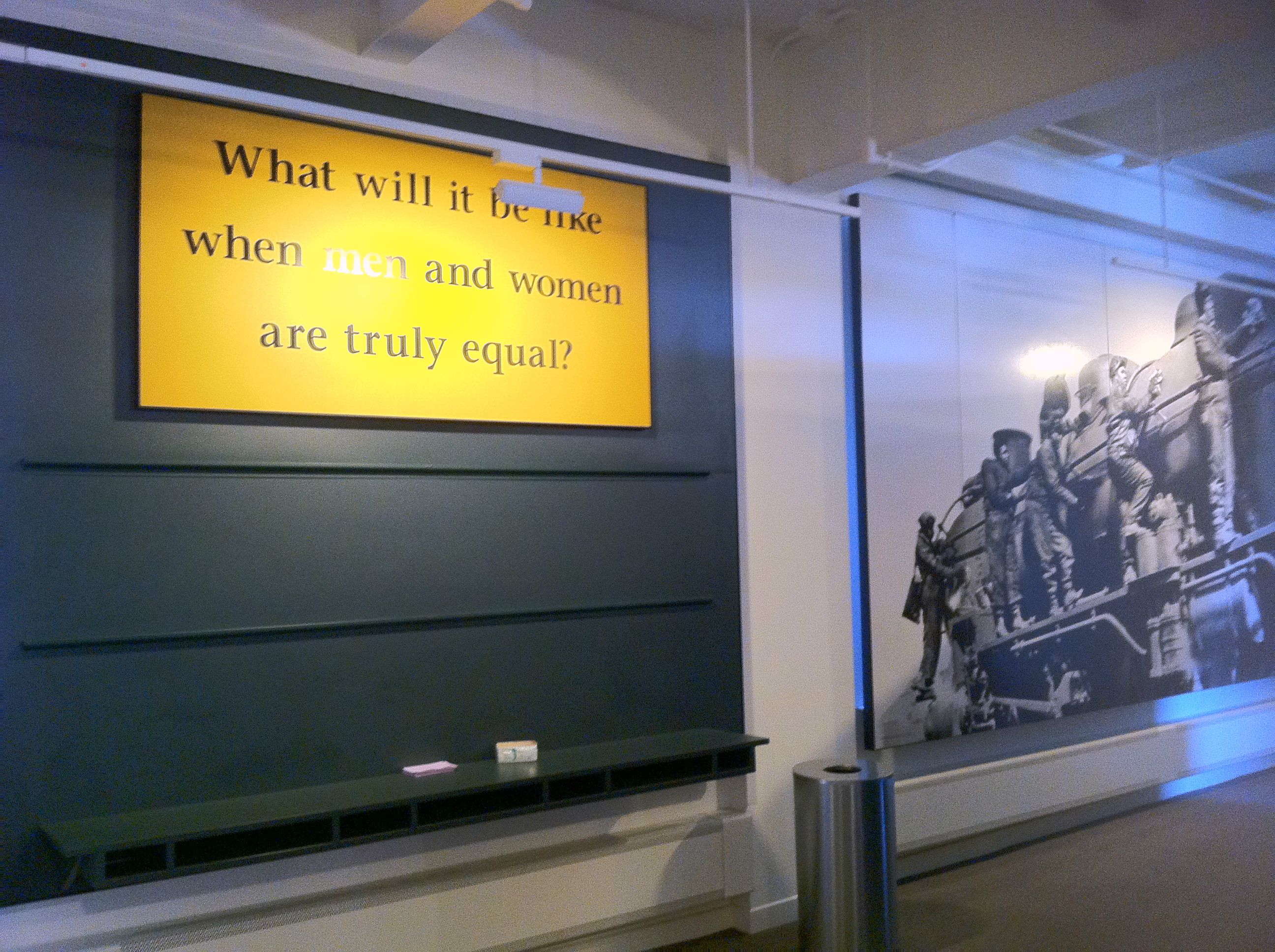

Talk-back boards also generate surprising revelations about museum visitors. Both SRM and WORI talk-back boards independently generated a significant number of responses about LGBTQ+ Rights. The WORI talk-back board posed the question “What will it be like when men and women are truly equal?” WORI Talk-back respondent language regarding LGBTQ+ themes changed significantly over time suggesting both a greater interest in such themes and broader social change. In the 1990s, the more common phrases used by visitors included the words “women” and “gay.” By the late 2000s, respondents spoke of “LGBT Rights”, “gay marriage”, and “gender” as opposed to “women’s rights” or “gay rights” and a few respondents specifically referenced transgender rights for the first time. These shifts in language resulted in curators recognizing the need to update certain aspects of their interpretation to better speak to visitors. Since this analysis, WORI organized multiple public events and initiated research into curating a new exhibit on transgender rights.11

At SRM, the presence of any LGBTQ+ themes was a surprise. “Gay Marriage” and “Gay Rights” were the seventh and twelfth most common word phrases respectively alongside other expected phrases involving religion, equality, and politics. Of the 95 LGBTQ+ themed responses, 82 expressed support, a ratio that is significantly more socially progressive than national averages.12 This is even more surprising given the sheer quantity of socially and politically conservative responses seen across the SRM responses, such as the eleventh most common phrase of “impeach Obama.” These results, once digested by museum staff, encouraged the creation of new exhibits or interpretation engaging LGBTQ+ Rights. As of this writing, SRM is highly open to such exhibits in the near future and is engaged in active research.13

Slavery was also an important topic of interest for staff at both sites. Slavery is readily apparent in SRM interpretation as exhibits engage questions of slavery, freedom, and equality with the hope that visitors would connect each theme to larger, more philosophical questions. From initial surveys, it was unclear as to whether or not these pedagogical goals were being met. Visitors simply did not—or would not—discuss difficult topics like race and freedom with museum staff face-to-face. From the talk-back board however, it was clear that many visitors made the desired connections (even though a handful of respondents rejected slavery as the primary cause of the Civil War). In contrast, WORI exhibits hardly discuss slavery at all, yet many visitors made connections between gender equality and race-based chattel slavery using abstract, emotion-driven language. A topic extraction analysis, where each response is broken down into stem words to discover common words that account for model variance, found a statistically significant percentage of respondents referenced sex equality (39.3%), social equality (9.2%), and economic equality (11.6%). Most respondents in the social equality category discussed racial equality, most poignantly expressed by the following respondent:

I think a lot of ‘being equal’ has to do with the defining of ‘power.’ Our society today is so power conscious that true equality between men and women must be something considered at the same time as ‘class power of the rich.’ just as slavery spurred an inspiration of gender equality, so should the political imbalance. (Response 2296.2010.10.9)14

Topic extraction results further suggested each talk-back question effectively engaged visitors on an abstract level as visitors commonly responded with sense-driven, emotive language regardless of topic.15

Altogether, these results demonstrate how talk-back boards can help amplify visitor voices that typically go unheard in museum spaces and, in making these voices heard, can help create a more meaningful experience, better exhibits and programming, and a more successful museum overall. This essay gives but a brief overview of results from a study with its broadest conclusion being that talk-back boards are best used to ascertain visitors’ sensibilities that are generally inaccessible via most other visitor studies methods. Additionally, talk-back boards should be designed to encourage visitor expressions of these sensibilities facilitated by thoughtful placement, a measure of solitude, and constant paper size. Finally, for anyone wishing to install their own talk-back board, each response must be given equal weight in final assessments. An anecdotal analysis tends to favor more thoughtful responses, such as Response 2296.2010.10.9 shared above, while a digital approach removes this particular element of bias. These results mean that this approach provides a relatively affordable and universally applicable visitor studies method unlike any other. Museums of all types could and should deploy such informal visitor studies methods to better understand and incorporate their stakeholders, deliver a better museum experience, and ultimately be better stewards of public history.

Bibliography

Binks, G., and D. Uzzel. “Monitoring and Evaluation: The Techniques.” In The Educational Role of the Museum, edited by E. Hooper-Greenhill, 298–301. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Bond, Nigel, Jan Packer, and Roy Ballantyne. “Exploring Visitor Experiences, Activities and Benefits at Three Religious Tourism Sites.” International Journal of Tourism Research 17, no. 5 (2014): 471–481. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2014.

Chen, Chia-Li. “Representing and Interpreting Traumatic History: A Study of Visitor Comment Books at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.” Museum Management and Curatorship 27 (2012): 379. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2012.720186.

Falk, J. H., J.J. Koran, L.D. Dierking, and L. Dreblow. “Predicting Visitor Behavior.” Curator 28 (1985): 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.1985.tb01753.x

Franco, Barbara (SRM Director). Interview by Josh Howard. March 14, 2015.

Franco, Barbara (SRM Director) and Pete Miele (SRM Director of Education and Museum Operations). Interview by Josh Howard. March 14, 2015.

Frank, Nathaniel. Awakening: How Gays and Lesbians Brought Marriage Equality to America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017.

Howard, Josh. “Talking Back with Post-It Notes: Informal Data Collection and Museum Visitors.” PhD diss., Middle Tennessee State University, 2016.

Macdonald, Sharon. “Accessing Audiences: Visiting Visitor Books.” Museum and Society 3 (2005): 119–136.

Miglietta, Anna, Ferdinando Boero, and Genuario Belmonte. “Museum Management and Visitor Books: There Might Be A Link?.” Museologia Scientifica 6 (2012): 94–95.

National Museum of American History. “Talking Back to the Museum.” Smithsonian.com, April 10, 2013. http://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/2013/04/talking-back-to-the-museum.html.

National Museum of American History. “Calendar of Exhibition and Events National Museum of American History December 2015.” Smithsonian.com, April 10, 2013. http://americanhistory.si.edu/press/releases/calendar-exhibition-and-events-national-museumamerican-history-december-2015.

National Museum of American History. “Introducing TalkBack Tuesdays.” Smithsonian.com, June 21, 2011. http://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/2011/06/introducing-talkback-tuesdays.html.

Noy, Chaim. “Pages as Stages: A Performance Approach to Visitor Books.” Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2008): 509–528.

Robinson, E.S. The Behavior of the Museum Visitor. Washington, DC: American Association of Museums, 1928.

Ron, Amos S. “Towards a Typological Model of Contemporary Christian Travel.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 4, no. 4 (2009): 287–297.

Ron, Amos S., and Jackie Feldman. “From Spots to Themed Sites—The Evolution of the Protestant Holy Land.” Journal of Heritage Tourism 4, no. 3 (2009): 201–216.

Rose, Vivien (WORI Chief of Cultural Resources). Interview by Josh Howard. July 18, 2014.

Sieburth, J.F., and D.S. Gleisner. “Talk Back—A Tool for Public Relations.” RQ 17 (1977): 17–18.

Simon, Nina. The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz, CA: Museum 2.0, 2010.

Wallace, Margot A. Consumer Research for Museum Marketers: Audience Insights Money Can’t Buy. New York: AltaMira Press, 2010.

Women’s Rights National Historical Park. “The Good, the Bad, and the Funny.” https://www.nps.gov/wori/planyourvisit/event-details.htm?event=7951D8D3-1DD8-B71B-0B22220F208C916A.

Women’s Rights National Historical Park. “Melissa Grace Park—-Music Event.” https://www.nps.gov/wori/planyourvisit/event-details.htm?event=E534C75F-1DD8-B71B-0B91F562A28E9CAB.

Women’s Rights National Historical Park. “WORI to Hold Discussion in Commemoration of LGBT Month.” June 18, 2016. https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/news/wori-to-hold-discussion-in-commemoration-of-lgbt-month.htm.

Women’s Rights National Historical Park Library. Talk-Back Board Collection. Seneca Falls, NY.

Notes

-

For example, see studies of museum fatigue. Robinson, The Behavior of the Museum Visitor, 7–42; Falk, Koran, Dierking, and Dreblow, “Predicting Visitor Behavior,” 249–257. ↩

-

Sieburth and Gleisner, “Talk Back,” 17–18; Simon, The Participatory Museum, ii. ↩

-

Museums occasionally deploy slightly different talk-back boards using dry-erase markers and whiteboards or online message board, chat room, or forum systems. These are comparatively uncommon and those of this type surveyed for this research were all intended to be temporary compared to the permanence of a “post-it note” talk-back board. For example, see the programs created from 2011 to 2013 by the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. National Museum of American History, “Introducing TalkBack Tuesdays”; National Museum of American History, “Talking Back to the Museum”; National Museum of American History, “Calendar of Exhibition and Events National Museum of American History December 2015.” ↩

-

Franco, interview; Rose, interview. ↩

-

Binks and Uzzel, “Monitoring and Evaluation,” 298–301; Macdonald, “Accessing Audiences,” 119–136; Wallace, Consumer Research for Museum Marketers, 32–33. ↩

-

Chen, “Representing and Interpreting Traumatic History,” 379; Noy, “Pages as Stages,” 509–528. ↩

-

All results and data are summarized in more depth in Howard, “Talking Back with Post-It Notes.” ↩

-

Miglietta, Boero, and Belmonte, “Museum Management and Visitor Books,” 94–95. ↩

-

Ron and Feldman, “From Spots to Themed Sites,” 201–216; Ron, “Towards a Typological Model,” 287–297. ↩

-

Bond, Packer, and Ballantyne, “Exploring Visitor Experiences,” 471–481. ↩

-

Women’s Rights National Historical Park (WORI), “The Good, the Bad, and the Funny”; WORI, “Melissa Grace Park—Music Event”; WORI, “WORI to Hold Discussion in Commemoration of LGBT Month.” ↩

-

Frank, Awakening, 272–276. ↩

-

Franco and Miele, interview. ↩

-

Women’s Rights National Historical Park Library, Talk-Back Board Collection, Seneca Falls, NY. ↩

-

Howard, 162–169. ↩

Author

Josh Howard,

Passel Historical Consultants, josh@passelhc.com,