A Committee of the Whole

Abstract

Anti-slavery societies have long served as the ostensible setting of early struggles for Black freedom and equal rights in the United States. By most accounts, nineteenth-century African American agitation happened under the umbrella of anti-slavery groups and their iconic, usually white leaders, such as William Lloyd Garrison. This view continues to serve as the default framework through which scholars organize their research on early African American history and culture. A post in late 2018 on the Black Perspectives blog, for example, comments that “the early meetings [of the Colored Conventions] focused primarily on the abolition of slavery.” Similarly, the early Black press has suffered neglect in proportion to the broader assumption that it was merely a subset of abolitionist publications, despite the assertions of specialists such as Frankie Hutton, Eric Gardner, and Jacqueline Bacon.1 A consequence of this framework is the prominence and broad familiarity with the work of white abolitionists, writers, and editors and the obscurity of their uncounted peers in Black-led newspapers, conventions, and many other organizations and spaces. This paper presents a macroscopic view of both anti-slavery and Black-led groups to dislocate those racial contours that inhibit scholarship in the archives of nineteenth-century collective Black life through social network analysis in four related arenas: Colored Conventions, the Black press, the Underground Railroad, and prominent anti-slavery societies.

I argue that the fractured structure of the communities revealed by this analysis precludes describing any of the major components as a single community, much less as encompassed by a single organization like the anti-slavery societies. Instead early Black organizing appears as much more diffuse and regionally distinct than has yet been recognized. This picture suggests a legion of new research opportunities to understand the regional diversity of antebellum activist communities, particularly as historians can recast existing frameworks away from anti-slavery and the Underground Railroad to represent more fully the broad, diverse, and shifting landscape of nineteenth-century Black organizing.

The data for this research necessarily comes from a wide variety of archives. No central collection of the Colored Conventions or Black press exists. Both conventions and newspapers blossomed in hundreds of locations across the United States. Given the scattered records of these histories, it has taken hundreds of hours over seven years to prepare these digital collections and associated datasets. These processes involved making interpretive decisions that shaped the digital materials.2 These decisions included common steps to establish scope and selection principles, but also the role of incomplete evidence in heterogeneous archives. How, for example, might a dataset describe a publication that is referenced by a number of its contemporaries, yet no physical copy is currently known to exist? My collaborators and I have determined to develop these materials on an iterative and inclusive model. Keep the fragmentary data, record the uncertainty, and broadcast the information widely. Access begets research, and perhaps new research will unearth new details, illuminate previously unknown connections, or point out why entirely different frameworks are needed.

The Colored Conventions show the need for iterative models. In 2012, a group at the University of Delaware began to assemble a digital collection of the minutes and proceedings from the Colored Conventions. Reprint volumes from the 1960s and 1970s contained approximately sixty conventions, but additional research has identified evidence for more than 450 African American conventions held during the nineteenth century. Given that scale, prior articles and books on the Colored Conventions have more in common with micro-history than longue durée views.3 For the period before Emancipation (1830-1864), the results of the Colored Conventions Project today include materials from forty-eight state and national Colored Conventions.

The history of the early Black press rewards just such an inclusive approach. Bibliographies and scholarly publications from the twentieth century provide accounts of approximately two-dozen antebellum newspapers and magazines edited by African Americans. Thanks to the wealth of digitized materials it is now possible to assert the existence of fifty-six publications with at least one hundred people who served as editors or publishers.4 Issues from over half of those publications (31) survive while the remaining (24) titles survive only as the attributed source of texts reprinted in other newspapers.

In contrast, the path from archival materials to actionable datasets for the Underground Railroad and anti-slavery societies is much shorter. In 1898, a historian named Wilbur Siebert published a book, The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom, with an appendix titled “Directory of the Names of Underground Railroad Operators” that listed more than three thousand names.5 The Boston Public Library (BPL) digitized their Anti-Slavery Collection of over 40,000 items, including the papers and correspondence of many of the most notable white abolitionists and anti-slavery societies.6 Like Siebert’s data, the Anti-Slavery Collection has an unequal coverage by race and region, but the coverage is not so uneven that the BPL’s metadata cannot be brought into conversation with the Colored Conventions to ask questions about regional networks over space and time.7 All of this data is vexed; some of it can be useful.

These extenuating conditions are worth elaborating because they justify the use of social network analysis. This paper investigates the structure of these communities. This focus on the collective, rather than more granular views, provides a way to characterize the relations across these four arenas at scale. Graphs of the relations between these collective bodies are less objective representations of historical links than charts of correspondences across multiple, large, digital archives. A collective graph is a proxy but not a substitute for the range of possible inquiries into the lived experiences recorded in these archives. At the same time, network analysis of these archives at scale shows that, despite frequent invocations of scarcity and loss, there is a lot of material to gather. The strongest illustration of this argument lies in the revived capacity of the Colored Conventions to organize nineteenth-century African American history.

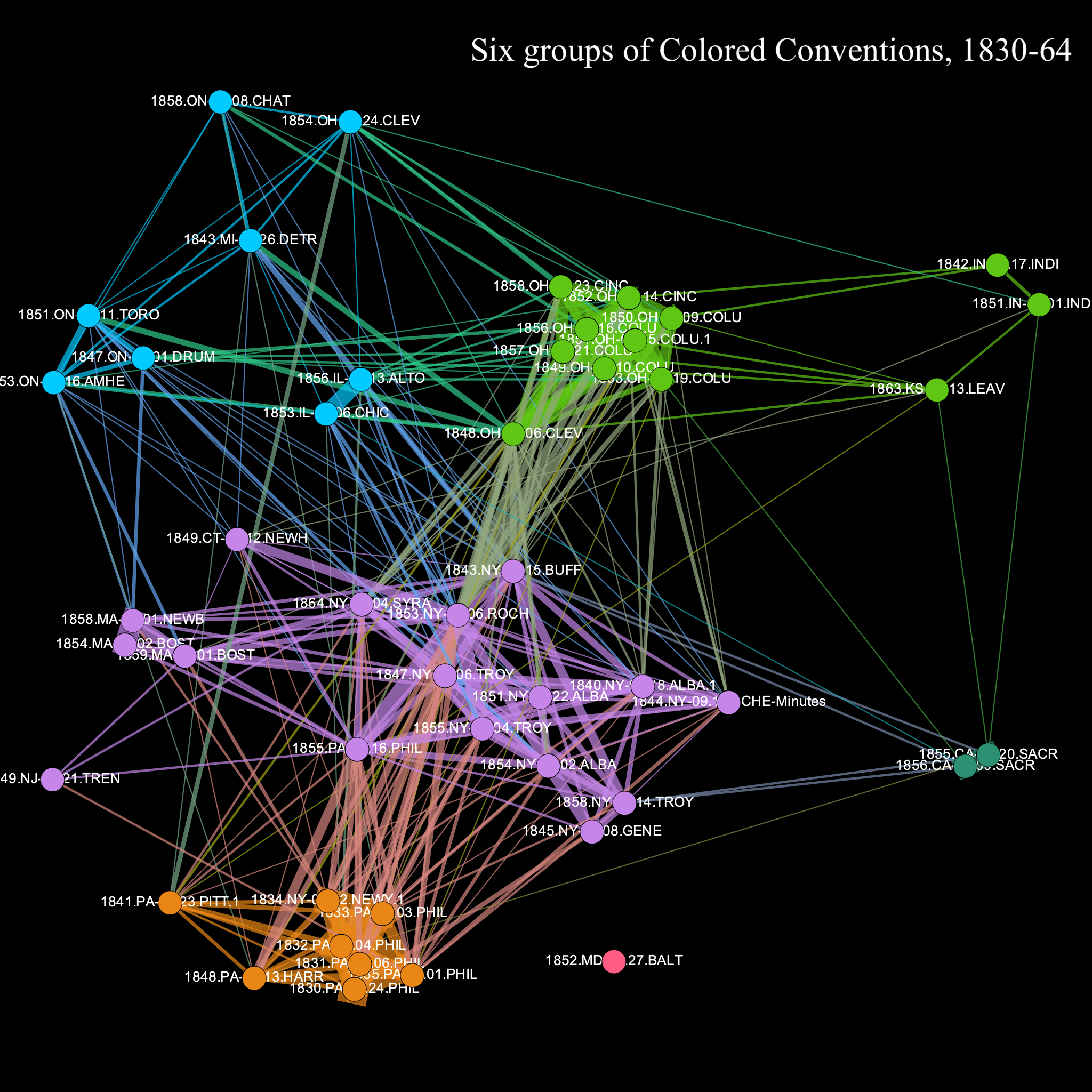

As a social network, the early Colored Conventions fall into six groups, each containing one or more convention, that constitute regional clusters. A full graph of the antebellum movement includes 1751 nodes (names and conventions) and 2306 links (lines that express attendance at a particular convention).8 More than four-fifths of the convention delegates did not attend more than one convention, so it augments the analysis to make a projection of the links from delegate-convention to shared attendance. As a result, the triads in this network [convention<=>delegate<=>convention] can be projected and simplified to dyads [convention<=>convention]. The shared attendance network of these dyads, when a basic modularity algorithm is applied, reveals the following six groupings: 1. Pennsylvania Conventions, 2. Border State Conventions, 3. California Conventions, 4. A Maryland Convention, 5. Northeastern Conventions, and 6. Transnational Conventions (see figure 1).9

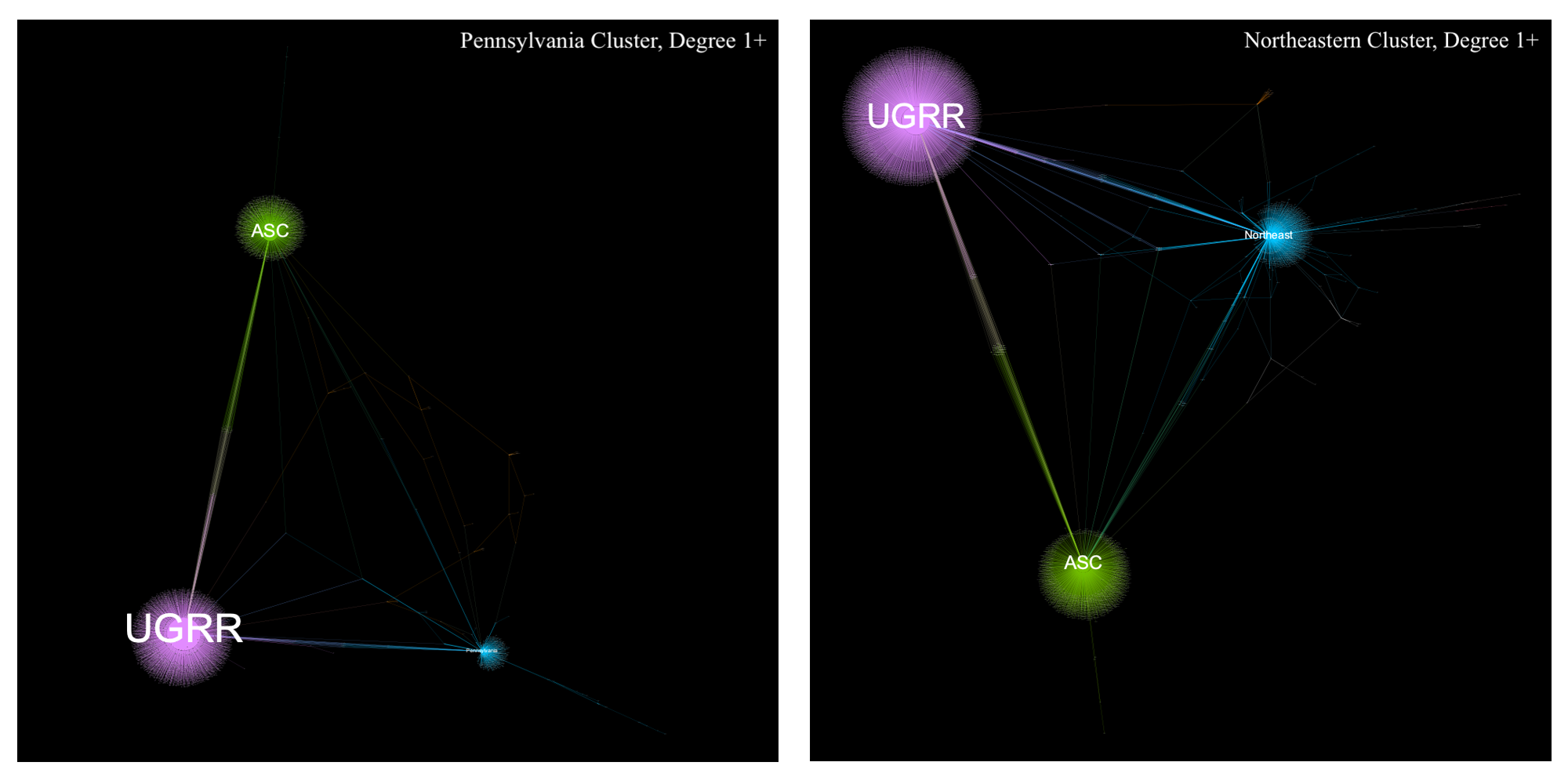

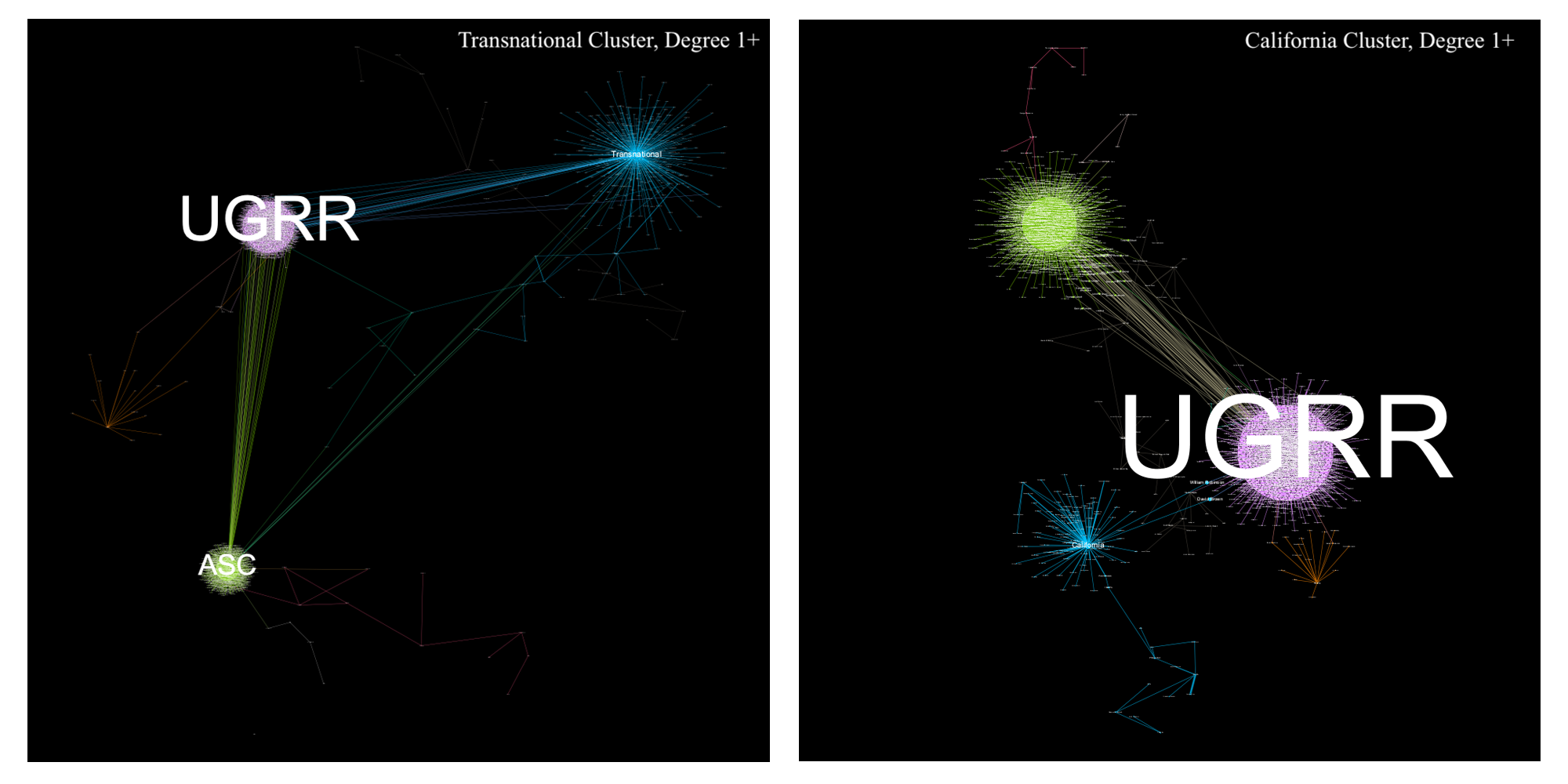

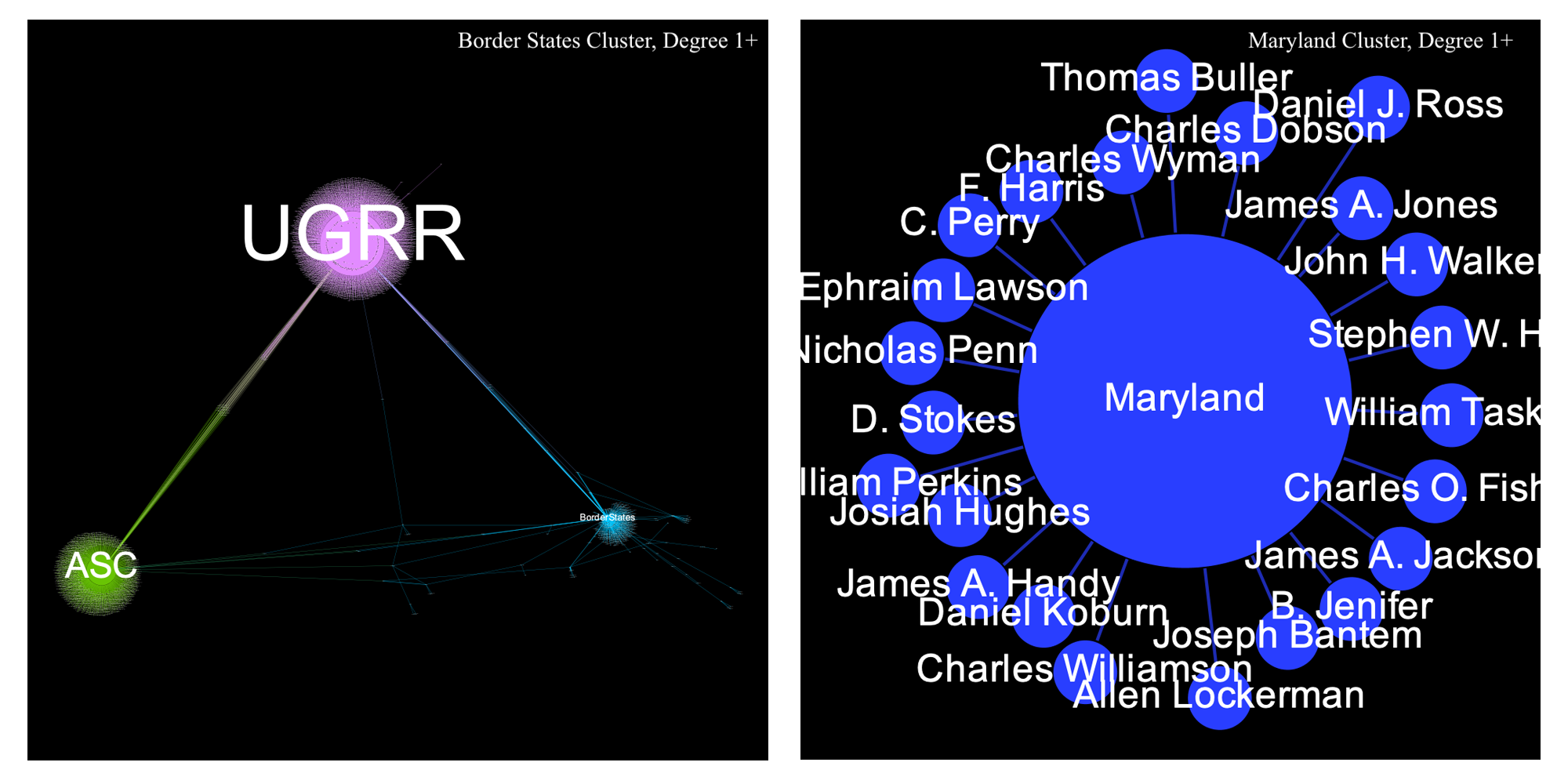

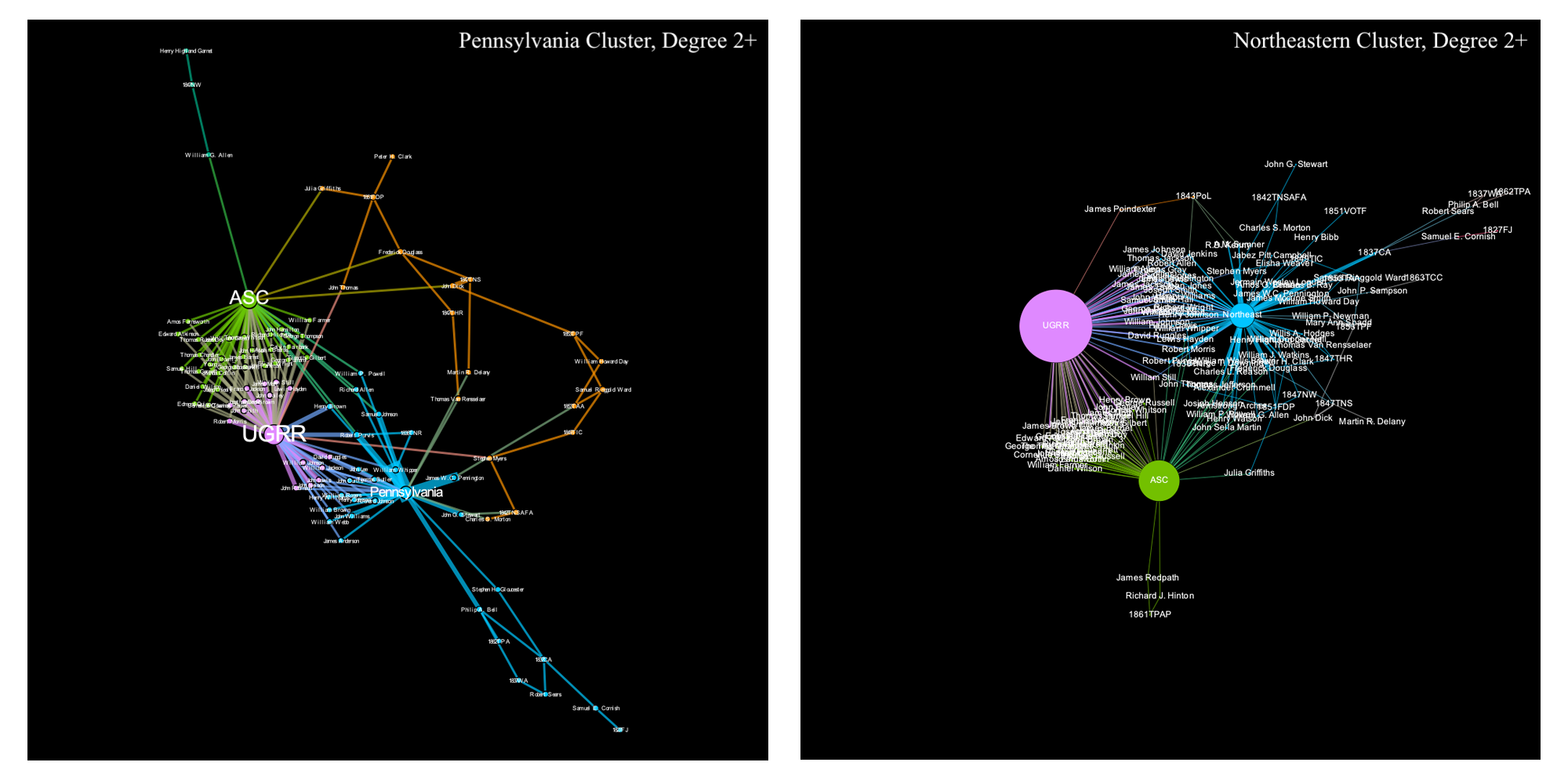

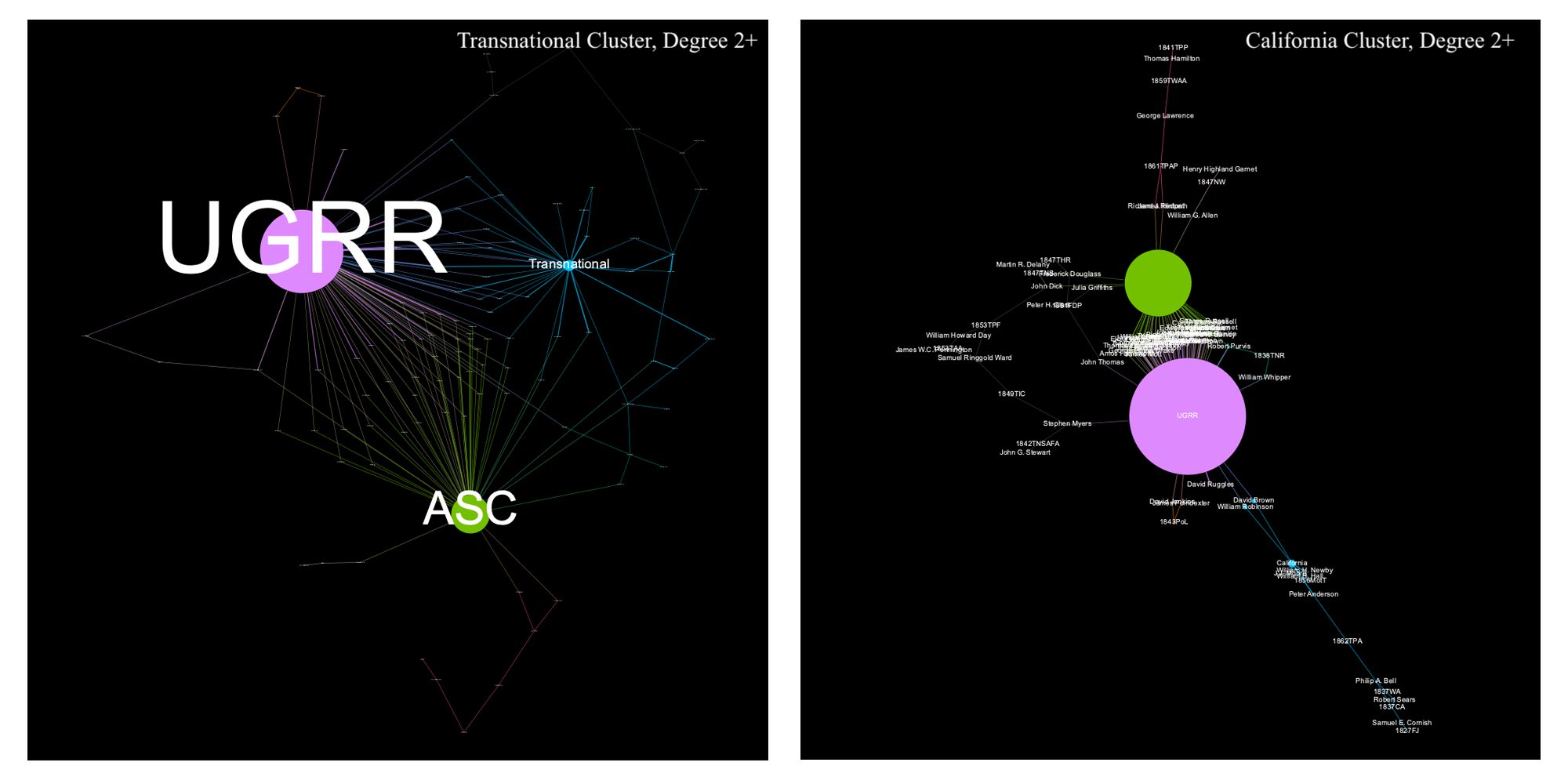

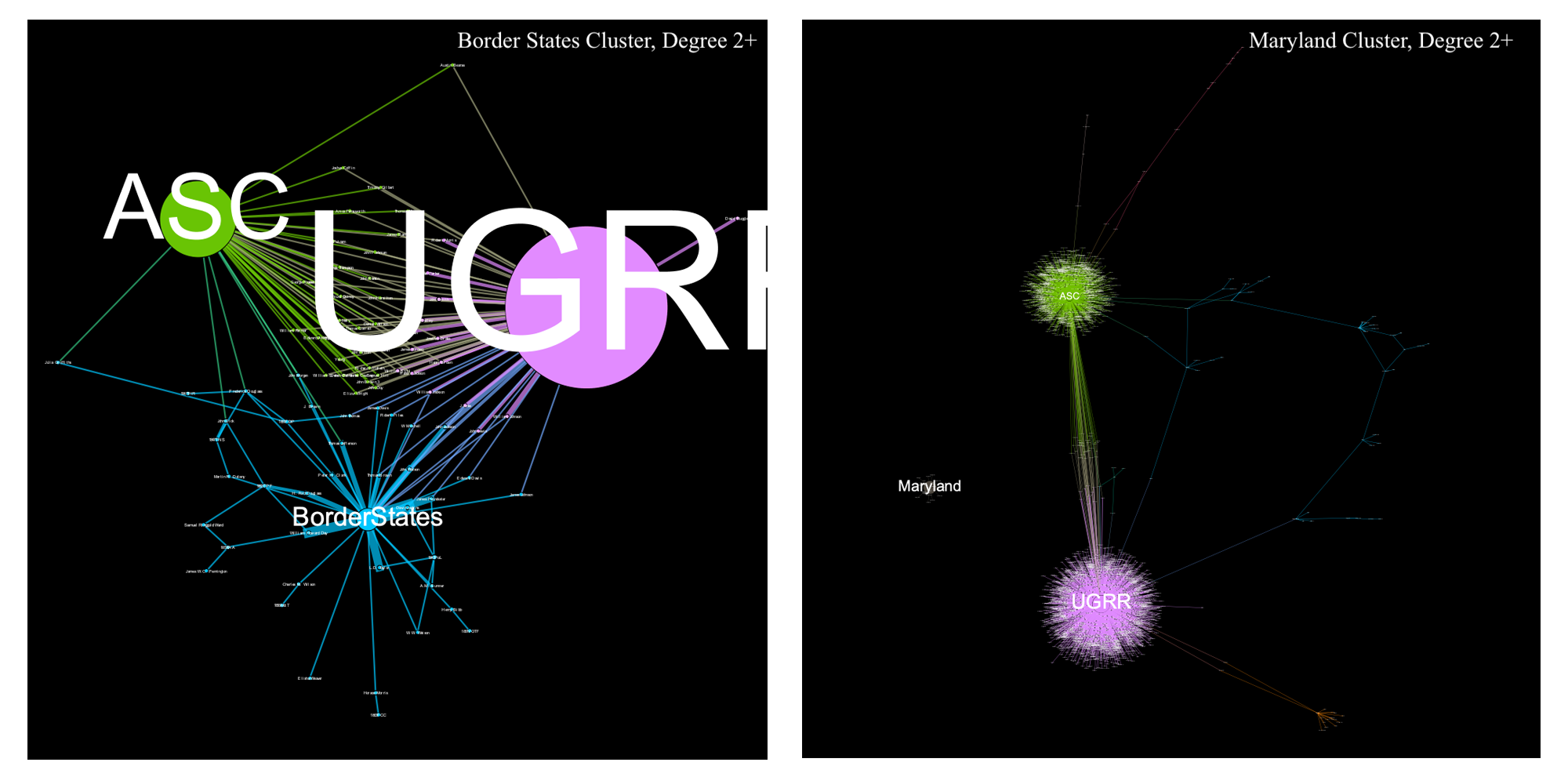

Figures two, three, and four show a comparison of the six regional communities of the Colored Conventions and their links with the Black press, the Underground Railroad (UGRR), and the anti-slavery societies (AS). The differences can be stark. The Maryland group is comprised of a single state convention, held in 1852, and has zero links to the other arenas. Where mob violence broke down the collective body of activists in Maryland, physical distance produces much the same effect for the regional community of Black California, which has only a few links with the UGRR and none with AS groups. The other four regions are much more connected to the other arenas, but even among these there are important regional differences. Some of these structural patterns are intuitive. In Pennsylvania, there are many more links to the UGRR than to AS groups. This pattern makes sense given the prominence of Black Philadelphia activists, such as the Still, Shadd, and Gloucester families. For the Northeastern conventions (roughly north and east of New Jersey) there are a much larger number of links forged by periodicals. The role of these periodicals as sites of exchange among the four arenas in the Northeast makes sense given that more than half of early African American newspapers were published in New York state. Newspapers also played a key role for the Transnational group of conventions that included upper Ohio, Illinois, Michigan, and into Ontario, Canada. The outlier in this comparative set of views is the group of Border State conventions. While a handful of states shared borders with slaveholding states, the conventions in Indiana and Ohio fostered different kinds of relationships with AS and UGRR groups.

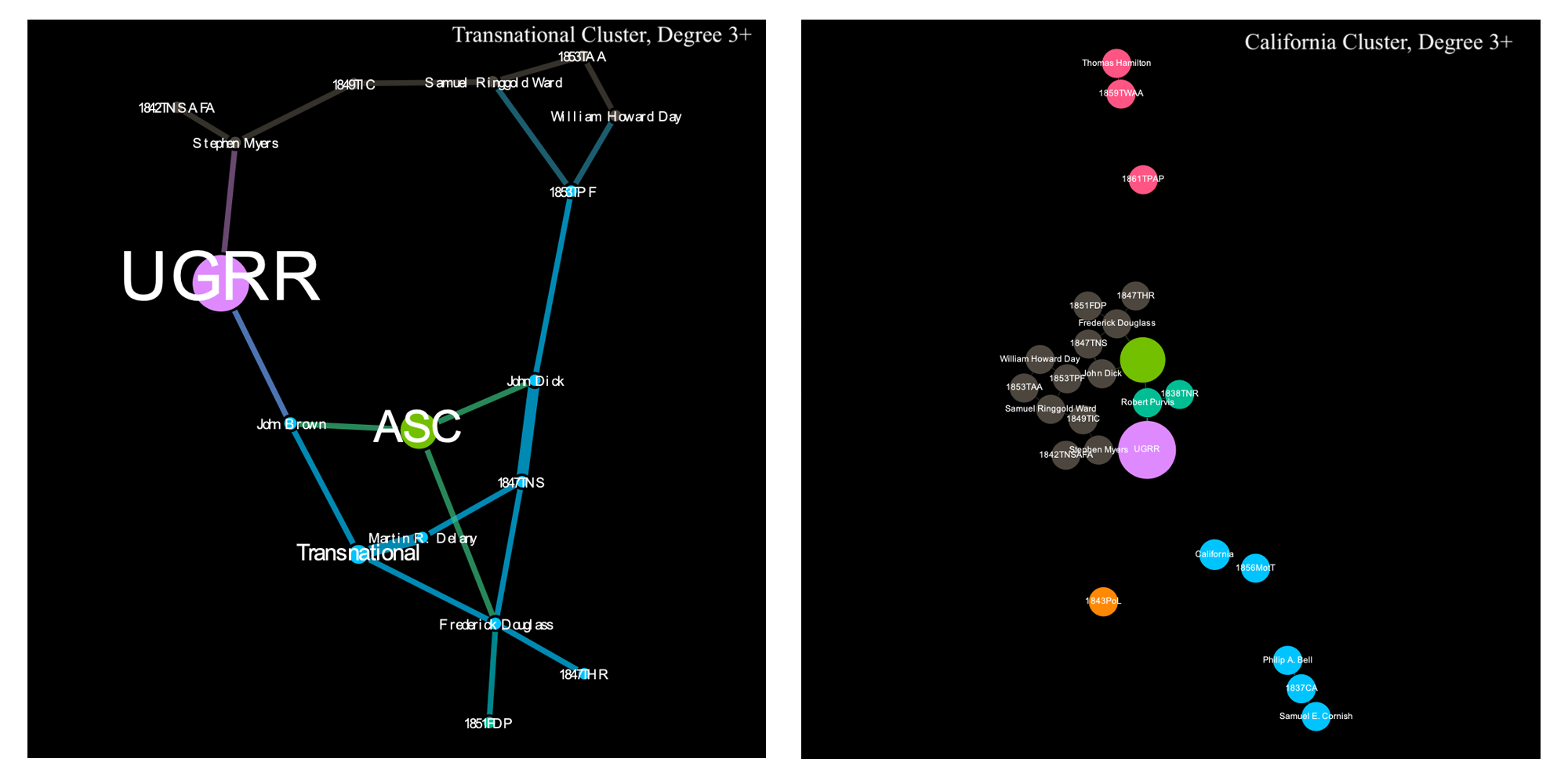

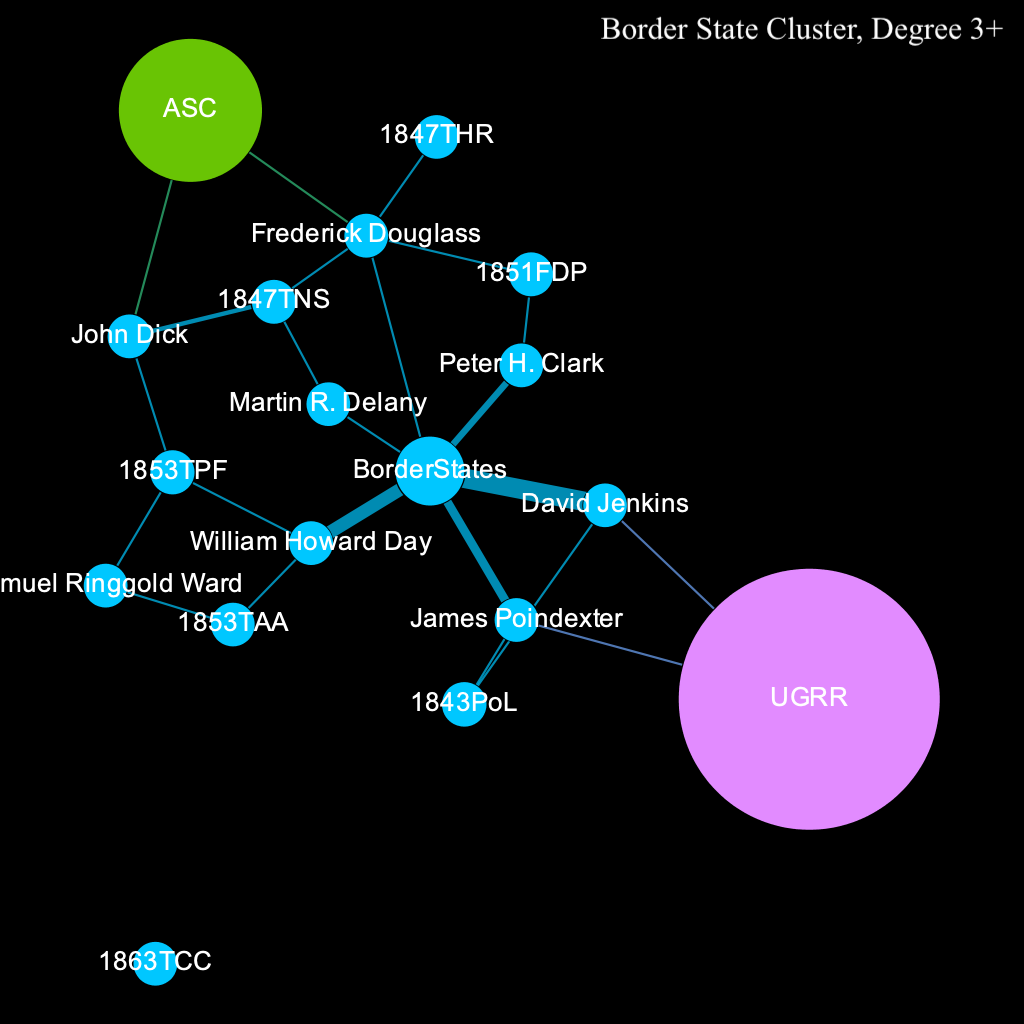

These collective relationships become clearer with a view focused on the people who created links across each of the four arenas (see figure 5). By filtering the network graphs to display only those entities with two or more connections, the following set of graphs are created in figures six through eight. Here, again, the differences are not subtle. In the sparser regional communities of California and Maryland, few or no connections bridge the four arenas. In Pennsylvania, the convention, UGRR, and AS groups are linked only through newspapers published outside the region—The North Star, the Aliened American and Stephen Myers’s various upstate New York papers. The Northeastern, Border State, and Transnational regional communities in this view have roughly even numbers of links distributed between the arenas. The small corps of individuals in these networks who bridged multiple communities are revealed as cross-communal brokers that constitute a starting point for future research on multi-modal activism and organizing.

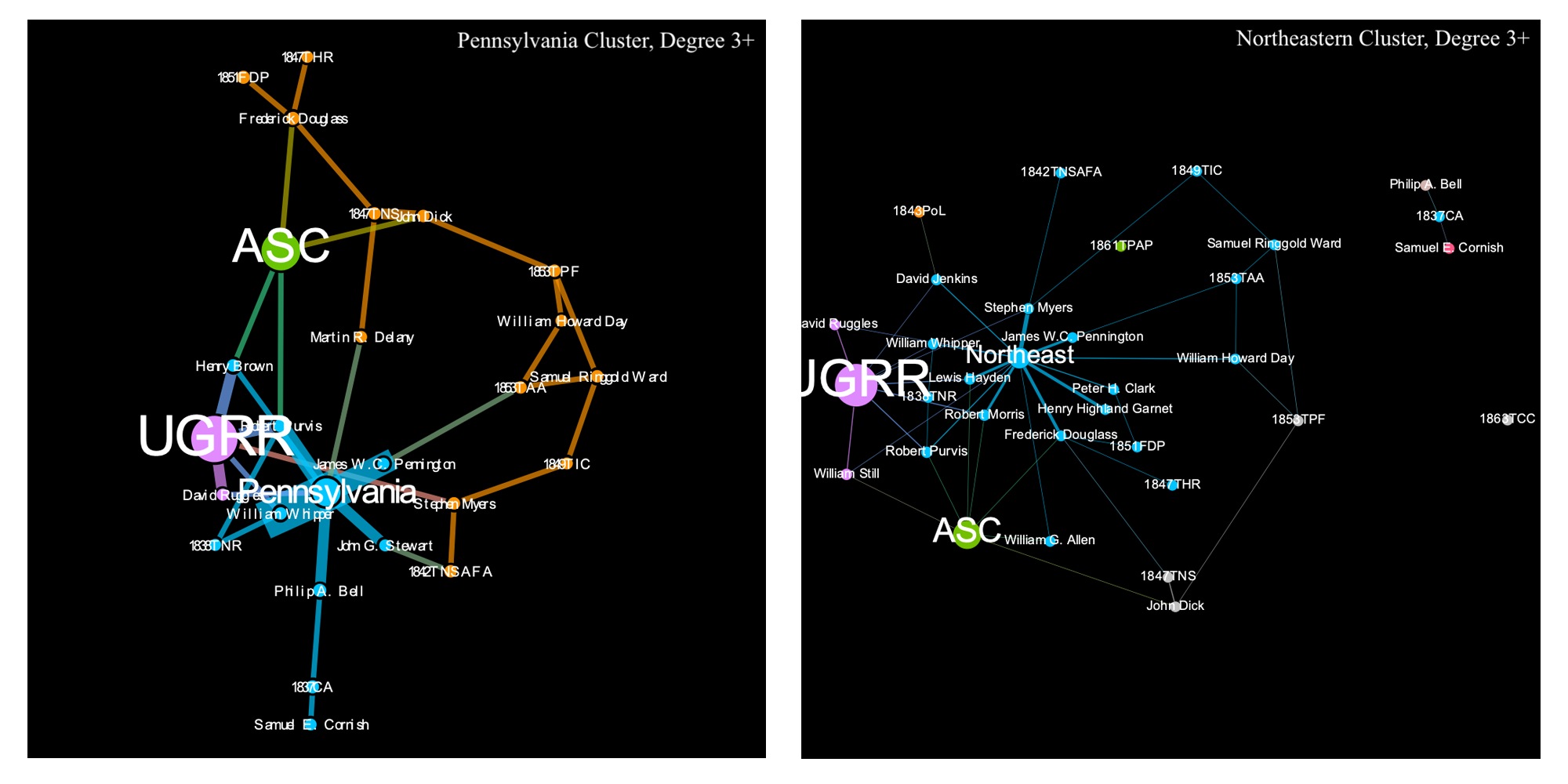

When the graphs are filtered to show only entities with three or more links, the resulting views (figure 9-11) show how marginal the Underground Railroad and anti-slavery societies were for the networks of Black activism. California and Maryland are isolated. For the Border States, only two men—David Jenkins and James Poindexter—show links to the UGRR. For people in the populations served by the Transnational groups, it is hard to assert that the Underground Railroad and anti-slavery groups did not play any role, yet in the graph the only connecting node is through the famed white abolitionist, John Brown. Brown only appears in the graph because of his role at the Chatham Convention (Ontario) on a single night not long before the raid on Harper’s Ferry. By contrast, the Pennsylvania and Northeastern regional communities are much denser, and invite additional scrutiny as they overlap in time very little. The Pennsylvania regional community might fairly be described as a graph of the national Black leadership in the 1830s, while the Northeastern graph contains the majority of the most well-known Black leaders, newspapers, and national conventions from the 1840s and 1850s. That is, these two graphs suggest that the shift from 1830s Pennsylvania to 1840s-1850s New York was driven by the simultaneous rise of Black conventions and newspapers adjacent to or separate from Underground Railroad or anti-slavery organizations.

Ultimately, the six communities described in this paper are not identical. Recognition of these regional differences pushes against flattening them into easily comparable units, but it also calls attention to the specific structures of nineteenth-century activist communities. Black leaders and activists created those communities in response to difference moments, contexts, and immediate or long-term needs. The shape and series of changes in each of the regional communities deserves far greater attention to gain greater understandings of the hemispheric and local contexts. Part of the work to be done involves more archival research in these arenas and their contemporaries—Black churches, Free Masons, schools, mutual aid societies, vigilance committees—as well as further inquiry in the archives of the Underground Railroad and anti-slavery networks.

That continuing work recalls one of the more common parliamentary gestures used in the Colored Conventions. During a meeting, participants would form committees and break out into separate discussions and tasks. Towards the end of a meeting, it would become time to reassemble and merge the various efforts into a larger, coherent, and heterogeneous collective body capable of surpassing any one of the committees. The meeting would then resolve itself into “A Committee of the Whole.” Perhaps this gesture might serve as a model for the next generation of digital histories of early Black organizing in the nineteenth-century United States.

Bibliography

Bacon, Jacqueline. Freedom’s Journal: The First African-American Newspaper. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2007.

Blondel, Vincent D., Jean-Loup Guillaume, Renaud Lambiotte, and Etienne Lefebvre. “Fast Unfolding of Communities in Large Networks.” Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 2008, no. 10 (October 9, 2008). https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008.

Gardner, Eric. Unexpected Places: Relocating Nineteenth-Century African American Literature. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2011.

Hutton, Frankie. The Early Black Press in American, 1827 to 1860. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1993.

Johnson, Jessica Marie. “Markup BodiesBlack [Life] Studies and Slavery [Death] Studies at the Digital Crossroads.” Social Text 36, no. 4 (December 1, 2018): 57–79. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-7145658.

McDaniel, Caleb. “Data Mining the Internet Archive Collection.” Programming Historian, March 3, 2014. https://programminghistorian.org/en/lessons/data-mining-the-internet-archive. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1477854.

Otis, Jessica (@jotis13). “Also, IMO, Creating a Dataset SHOULD Be Considered Scholarship. The Interpretive Decisions We Make While Structuring, Creating, & Building out a Dataset Are Just as Important as the Work We Do in Interpreting It b/c Those Decisions SHAPE the Interpretations We Can Make #crdh2019.” Twitter, March 9, 2019. https://twitter.com/jotis13/status/1104410030458265600.

Notes

-

See Hutton, The Early Black Press in American, 1827 to 1860, 3–4; Gardner, Unexpected Places 5–7; and Bacon, Freedom’s Journal, 2. ↩

-

See Johnson, “Markup Bodies,” 58–65. In addition, as Jessica Otis commented on Twitter during the Current Research in Digital History conference in 2019, “creating a dataset should be considered scholarship. The interpretive decisions we make while structuring, creating, & building out a dataset are just as important as the work we do in interpreting it b/c those decisions SHAPE the interpretations we can make.” The notion of dataset creation as scholarship deserves greater attention, especially for early African American studies. Jessica Otis, “Creating a Dataset.” ↩

-

All scholarship that engages with some moment in the conventions appears online at http://coloredconventions.org/bibliography. ↩

-

All information in this essay related to the early Black press is available at http://jim-casey.com/enap/. ↩

-

Owing to the secrecy of the UGRR and the elapsed time, the appendix is far from comprehensive. Unequal racial coverage in the appendix is only one of many problems with Siebert’s data. Siebert notes in the appendix that “the names of colored operators are marked with a †.” Revealingly, Siebert assumes the default race of UGRR operators as white. The distribution of operators by race illustrates his perspective. Only 5% (151) of the operators are marked as Black. That obviously does not reflect the reality of the thousands of people of color who assisted refugees from the South. Even with these deficits, historians from Eric Foner to Cheryl LaRoche find the 1898 appendix nevertheless useful for engaging with the larger patterns of the Underground Railroad. ↩

-

The Anti-Slavery Collection began as a collection of the personal papers of William Lloyd Garrison, as collected by his family, and several of his closest colleagues and fellow abolitionists. While not exhaustive, the BPL-ASC includes many of the most notable white abolitionists and the American, Massachusetts, and New England Anti-Slavery Societies. It would be difficult to argue that the collection does not offer a representative sample of white-led anti-slavery societies. ↩

-

Data deployed in this chapter about the Anti-Slavery Collection comes from “Data Mining the Internet Archive.” ↩

-

The process of de-duplicating names required three corresponding data points for each entry. The data points under consideration include first and last names, titles, city of residence, and/or attendance at previous conventions within the same state. Variant spellings of names and the use of initials for first and middle names were very common. I chose to reconcile them only if additional details in the minutes and proceedings could corroborate their identity. Additional credit should be given for the many contributors to the Transcribe Minutes transcription project. ↩

-

On modularity, see Blondel et al, “Fast Unfolding of Communities,” 1. ↩

Author

Jim Casey,

Center for Digital Humanities, Princeton University, jccasey@princeton.edu,