Century of Black Mormons

A Preliminary Interpretation of the Data

Abstract

In the months leading up to the 2012 presidential election between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, a few media outlets reinforced the public perception that members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (commonly called Mormons) were predominantly white.1 Reporter Jessica Williams from Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show interviewed five Black Mormons and then called them “mythical creatures, the unicorns of politics.” She asked if the five whom she met comprised the entire population of Black people in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints?2 Susan Saulny, a reporter for the New York Times, similarly speculated in a Times online video that there were only a “very small number” of Black Mormons, a “couple of thousand max,” or somewhere between “500 to 2,000.”3 Likewise, Jimmy Kimmel asked on Jimmy Kimmel Live, “Are there Black Mormons? I find that hard to believe.”4

Century of Black Mormons (CBM) is a digital history project designed to not merely answer these questions but to historicize them.5 The first documented black person to join this American born faith was Black Pete, a former slave who was baptized in 1830, when the fledgling movement was less than a year old.6 Other Black Saints trickled in over the course of the nineteenth century (more than 280 identified so far) and are woven into the Mormon story. At least two black men were ordained to the faith’s highest priesthood in its first two decades, and the database will document many more who slipped past the faith’s 1907 “one drop” policy. Yet by the beginning of the twentieth-century Mormons themselves had erased black pioneers from their collective memory and solidified race-based priesthood and temple restrictions in their stead.7 On the inside and on the outside Black Mormons were lost to history.

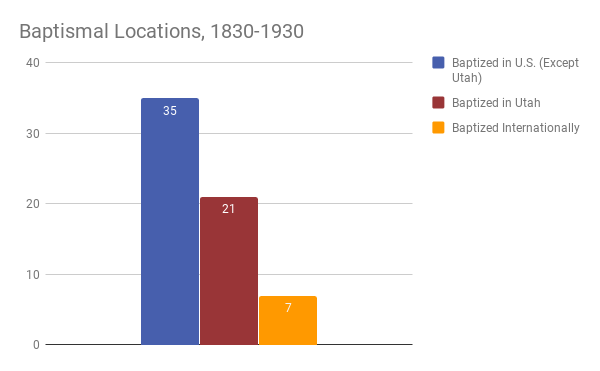

Century of Black Mormons seeks to name, number, and identify all known people of black-African descent baptized into the church between 1830 and 1930 and thereby recover what was lost. At its core CBM is a social history project organized around biographies of Black Latter-day Saints.8 Researchers collect primary source documents such as baptismal records, census records, journal entries, diaries, and vital records which are made publicly available in a digital viewer at the bottom of each biography. A timeline feature (see figure 1) tracks dates of baptism and a map (see figure 4) pinpoints location of baptisms. The database thus seeks to be a principal repository for primary and secondary source information for scholars and laypeople alike on what it meant to be black and Mormon during the faith’s pioneering century.

As scholars of religion in the United States have begun to challenge the perception of a monolithic “Black Church,” they have explored what religious life looked like for African Americans who worshipped in predominantly white churches, with Catholics, Congregationalists, and Mennonites as three examples of groups that have been studied.9 Century of Black Mormons adds a digital public history project to that conversation as it offers an historical lens into integrated worship and racial conversions in the Latter-day Saint tradition.10

The bulk of the scholarly attention on Mormonism and race (my own included) has focused on the white male LDS hierarchy and their decisions over the course of the nineteenth century to restrict converts of black-African descent from priesthood ordination and temple worship.11 What that story overshadows is the fact that Mormonism has always included baptism and confirmation for people of black-African descent as well as integrated Sunday worship (messy though it was), from 1830 to the present.12 The scholarly focus on temples and priesthood have thus obscured efforts at understanding the Mormon racial story from the vantage point of Black Saints in the Sunday pew. Historians cannot begin to piece together that puzzle without first documenting the existence of Black Mormons and understanding the basic contours of their life in the faith.

The story of race and Mormonism was shaped by the fact that the church includes a lay priesthood of male believers and a dual worship structure that consists of Sunday services in chapels and weekday rituals in temples. On Sunday, parishioners partake of the sacrament of the Lord’s supper and promise to follow Jesus Christ. Additional rituals are offered in temples on weekdays to adherents who meet specified standards. Proxy baptisms for deceased persons, marriages (or “sealings” for eternity), washing and anointing rituals, and a ritualized enactment of the biblical creation narrative called the “endowment” are all performed in temples. Membership in the faith and Sunday services have always been open to people of all ethnic and racial backgrounds, but white leaders eventually barred Mormons of black-African descent from temple rituals (except for proxy baptisms) and the lay priesthood. LDS leader Brigham Young began this form of discrimination in 1852 and Joseph F. Smith (nephew of founding prophet Joseph Smith) solidified it by 1908. The racial restrictions remained in force for most of the twentieth century until then leader Spencer W. Kimball removed them in 1978. Despite such policies, CBM demonstrates that people of black-African descent continued to join and practice the faith.

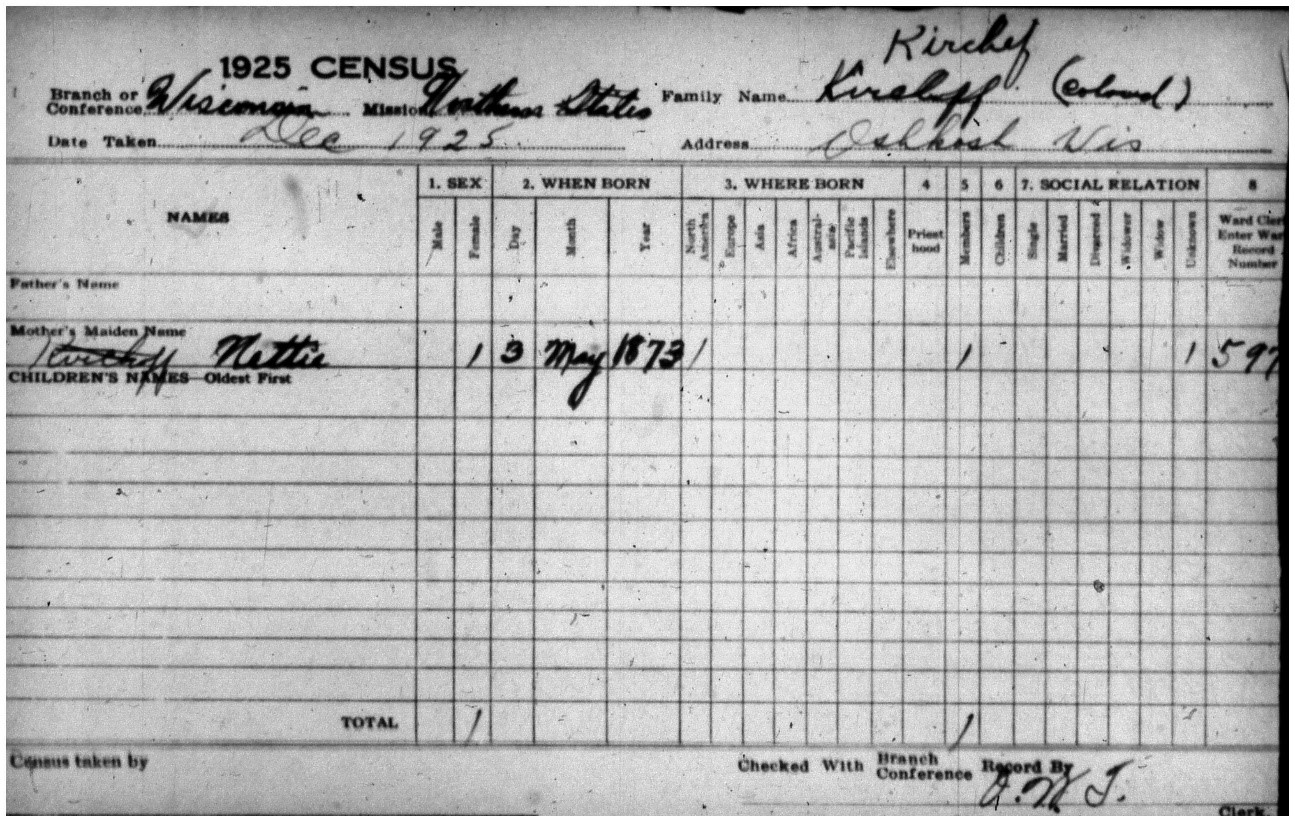

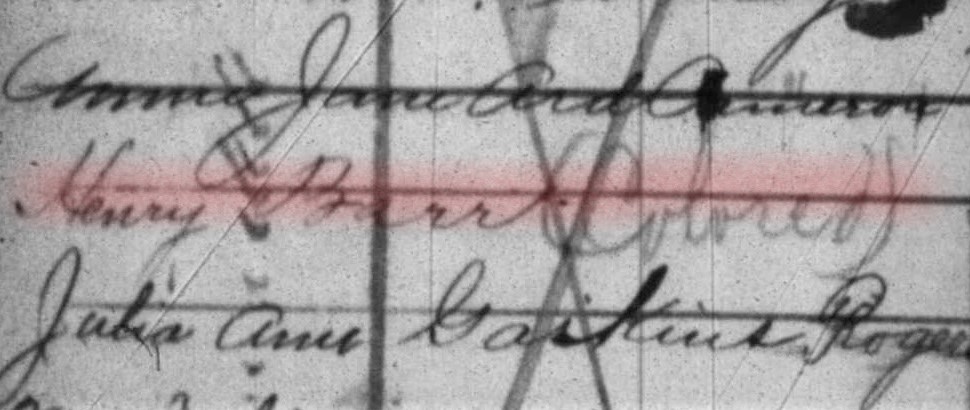

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has never officially tracked membership by race and has therefore never attempted to document how many of its members were of black African descent. While LDS baptism and confirmation records do not contain racial categories, those who created those records sometimes did note race in the margins of the documents they made. A clerk or missionary might scrawl “colored” next to a person’s name (see figures 2 and 3), a fact that highlights the way in which white was deemed normal and a variation from white was considered noteworthy.13 This is one of the ways that CBM researchers have been able to identify individuals to include in the database along with crowdsourcing, journals, diaries, and other records.

As of July 2019, Century of Black Mormons contained nearly seventy individuals whose files were complete and publicly available. Their stories and the corresponding metadata highlight two early findings. First, integrated Sunday worship services varied across time and space and reveal both racism in the pews as well as evidence of racial inclusion. Second, similar to what scholars have documented about white LDS conversions, kinship networks were important factors in the spread of Mormonism among black converts and also influenced the multigenerational contours of their faith.14

What did Sunday worship look like for Black Latter-day Saints, given the evolving racial policies of their church? Jane Manning James, one convert in 1843 remembered in an autobiography written late in life that she joined the New Canaan Congregational Church in Wilton, Connecticut, when she was fourteen years old but she “did not feel satisfied.” She recalled, “it seemed to me there was something more that I was looking for.” She claimed to find it eight years later when Latter-day Saint missionaries passed through the region and baptized her. Within a few weeks she recalled, “the Gift of Tongues came upon me.” She then experienced other spiritual manifestations that confirmed her in her new faith. Although by the 1880s LDS leaders denied her temple admission for the highest rituals of her faith, she did participate in baptisms for her deceased ancestors in two LDS temples and continued to exercise the gift of tongues, faith healings, and testimony sharing in integrated congregations throughout her life.15

William and Marie Graves were Black Saints who first encountered Mormon missionaries street-preaching in Oakland, California. In November 1911, the missionaries baptized and confirmed William and Marie as Latter-day Saints. In 1920, when the couple traveled to Georgia to visit friends, they sought out the Atlanta LDS congregation but were told that black people were not welcome. “I never had nothing to hurt me like that in all of my life” Marie wrote.16 They returned to Oakland and continued to worship in their integrated congregation for the rest of their lives. In fact, when William died in 1940 he left all remaining proceeds from the settlement of his estate to his LDS congregation in Oakland. William and Marie regularly participated in worship services in their congregation, bearing “testimony,” saying prayers, and donating money to charitable causes.17

Meanwhile in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, Esther Jane “Nettie” Kirchhoff was a founding member of the tiny LDS branch organized there in 1904. Her husband Richard was a German-born immigrant and Nettie was of mixed racial ancestry. She became Sunday School Secretary in an atypical mixed gender and mixed-race Sunday School presidency.18 She also taught Sunday School, as did Elijah Banks, another black convert, this time in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1899.19 By all accounts, the Graves along with Elijah Banks and Nettie Kirchhoff were valued members of integrated congregations throughout their lives.

In contrast, Esther Jane James Leggroan, Jane Manning James’s granddaughter, worshiped in the Wilford Ward in Salt Lake City, but mostly on the margins. She felt the sting of prejudice when fellow congregants refused to sit by her and her family. They were accepted as members but were not encouraged or given opportunities to fully participate.20 Frances Leggroan Fleming also recounted the racism she experienced in her Salt Lake City congregation: “I was taught you can’t go into the temple, you’re not the right color. You’re not good enough,” she said. For a time she attended the Methodist Church in Salt Lake City and refused to raise her daughters as Latter-day Saints in an effort to shield them from the same type of prejudice she had experienced. Even still, she returned to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints after her husband converted and remained a practicing member for the rest of her life.21

The difference may have been that the Graves, Kirchhoff, and Banks lived in small and struggling congregations in locations distant from the heart of Mormonism which needed and valued all congregants versus Leggroan and Fleming who lived in Salt Lake City in established “wards” or congregations which could afford to racially marginalize people and yet still fully function. Fourteen biographies thus far offer evidence of racial prejudice related to worship experiences.22 Of those fourteen, the majority occurred in congregations in Utah. These results may be amplified by the fact that the source base for some Utah biographies includes oral interviews and therefore the evidence of prejudice is more readily available than for outlying locations. Moreover, there are exceptions to this pattern. Paul Thomas Harris, for example, a convert in 1910 in South Africa, encountered white coreligionists who refused to allow Harris to worship with them altogether. In response, missionaries administered the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper to him in his home.23 Similarly, in Cincinnati, Ohio, white members made it clear to Len and Mary Hope that they were not welcome at Sunday services. But when the couple moved to Salt Lake City, they worshiped in an integrated congregation.24 Sunday worship for Black Mormons thus varied across time and space. Lack of sources makes it impossible to know what worship looked like in all situations, but the database is yielding clues previously unavailable.

The database is also shedding new light on kinship conversion networks and multigenerational families. Early converts such as free blacks Elijah Able (an ordained Seventy in the priesthood) and Jane Manning James migrated to Utah and helped to establish a pioneering black community in the intermountain West. In 1870, Susan Gray Reed Leggroan and her husband Ned migrated to Utah with Ned’s sister and her husband, Amanda and Samuel Chambers, all of whom were formerly enslaved.25 Samuel converted in Mississippi while enslaved and then waited until after the Civil War to earn enough money to migrate to Utah. Amanda, Susan, and Ned joined him. Three years after their arrival in Utah, Ned and Susan converted and went on to preside over a multi-generational family of Black Mormons. There are already eleven of their descendants included among the completed profiles in the database with at least eight more family members under research.

Elsewhere, in Tylertown, Mississippi, missionaries baptized Samuel Magee in 1908. Within four months, his wife Ardella Bickham Magee followed him into the faith and their children joined after that. In total eleven members of the Magee family converted.26 Ardella gave birth to her youngest son at the time of the family’s conversion and she and Samuel named their new baby Moroni after a Book of Mormon prophet.27 Kinship networks were clearly important in Black Mormon conversions. Of the currently completed profiles, seventy percent were married or related to another person who also converted.

Many of the descendants of the pioneering black families who migrated to Utah intermarried and formed a core group of second, third, fourth, and fifth generation Mormons.28 In fact, two of Elijah Able’s great-granddaughters, ArLene and Mary June, were baptized in 1930 and 1934 respectively.29 Their baptisms represent four generations and over 100 years of Ables as Latter-day Saints. Several generations of interracial marriages also likely meant that later members of the Able family eventually passed as white. Able’s son Moroni and grandson Elijah R. Ables, although identified in some census records as black and mulatto, were both ordained Elders in the LDS lay priesthood in 1871 and 1935 respectively, marking at least three black priesthood holders in the same family.30 Jane Manning James’s children were also baptized but most left Mormonism before they died, likely in response to the shrinking space for full black participation in their chosen faith.31 Even still, Century of Black Mormons already includes fourth and fifth generation descendants of James and her husband Isaac, a fact that should prompt new understandings of Mormonism’s racial story across generations.32 Rather than one or two notable Black Latter-day Saints as the focus of the Black Mormon story, Century of Black Mormons has documented a number of pioneering black families whose legacies endured for more than a century.

In fact, the map feature in Century of Black Mormons (see figure 4) has already revealed an interesting pattern of conversion, especially when combined with the database’s timeline. Second, third, fourth, and fifth generation Mormons represent a growing number of Utah based baptisms and so far account for all of the baptisms between 1873 and 1891 (see figure 5). Of the twenty-one Utah baptisms thus far, sixty-five percent were of people who were second generation or later Mormons. As Mormonism reinvigorated its missionary program by the 1890s in the wake of a federal anti-polygamy crackdown, baptisms outside of Utah followed through the 1930s.

In sum, Century of Black Mormons is yielding new clues about the contours of integrated Sunday worship among Latter-day Saints with evidence of both the challenges and promises of racial integration. The project further illustrates the significance of kinship conversion networks among Black Mormons with an overwhelming majority of people in the database married or related to someone else who was baptized. Those networks likely made it easier to pass on the faith, with some Black Mormon families extending over five generations. Clearly, there are Black Mormons and there always have been too. Their lives add complexity to a largely white Mormon narrative and teach new lessons about the intersections between race, region, and religion in American history.

Bibliography

Allison, Christopher M. B. “Layered Lives: Boston Mormons and the Spatial Contexts of Conversion.” Journal of Mormon History 42, no 2 (April 2016): 168–213. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/jmormhist.42.2.0168

Bailey, Julius H. Down in the Valley: An Introduction to African American Religious History. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt17mcs0d.

Boles, Richard J. “Dividing the Faith: The Rise of Racially Segregated Northern Churches, 1730–1850.” Ph.D. diss., George Washington University, 2013.

Boles, Richard J. “Documents Relating to African American Experiences of White Congregational Churches in Massachusetts, 1773–1832.” The New England Quarterly 86, no. 2 (June 2013): 310–323. https://doi.org/10.1162/tneq_a_00280.

Bringhurst, Newell G. Saints, Slaves, & Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People within Mormonism. 2nd Edition. Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2018.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Record of Members Collection. Logan 10th Ward. CR 375 8, box 3765, folder 2, image 550 and 578. Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Record of Members Collection. Logan 10th Ward. CR 375 8, box 3765, folder 1, image 233. Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Coleman, Ronald G. “‘Is There No Blessing for Me?’: Jane Elizabeth Manning James, A Mormon African American Woman.” In African American Women Confront the West, 1600–2000, edited by Quintard Taylor and Shirley Ann Wilson Moore. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003.

Cressler, Matthew J. Authentically Black and Truly Catholic: The Rise of Black Catholicism in the Great Migration. New York University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9781479841325.001.0001.

Driggs, Ken. “‘How Do Things Look on the Ground?’: The LDS African American Community in Atlanta, Georgia.” In Black and Mormon, edited by Newell G. Bringhurst and Darron T. Smith. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt1x74nc.

Embry, Jessie L. “Speaking for Themselves: LDS Ethnic Groups Oral History Project.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 25 (Winter 1992): 99–110. https://www.dialoguejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/sbi/articles/Dialogue_V25N04_101.pdf.

Embry, Jessie L. Black Saints in a White Church: Contemporary African American Mormons. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1994.

Emerson, Michael O. and Christian Smith. Divided by Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Glaude Jr., Eddie S. African American Religion: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780195182897.001.0001.

Graves, Marie to Heber J. Grant. 10 November 1920. As quoted in Ardis E. Parshall, “Marie and William Graves: The Part I Withheld.” Accessed 1 February 2019. http://www.keepapitchinin.org/2018/09/14/marie-and-william-graves-the-part-i-withheld/.

Harris, Matthew L., and Newell G. Bringhurst. The Mormon Church and Blacks: A Documentary History. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015.

Hawkins, J. Russell, and Phillip Luke Sinitiere, eds. Christians and the Color Line: Race and Religion after Divided by Faith. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199329502.001.0001.

Jackson, W. Kesler. Elijah Abel: The Life and Times of a Black Priesthood Holder. Springville, Utah: CFI, 2013.

Johnson, Karen Joy. “Healing the Mystical Body: Catholic Attempts to Overcome the Racial Divide in Chicago, 1930–1948.” In Christians and the Color Line: Race and Religion after Divided by Faith*, edited by J. Russell Hawkins and Phillip Luke Sinitiere. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199329502.003.0003.

Mauss, Armand L. All Abraham’s Children: Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003.

McBride, Matthew. “Black Pete.” Accessed October 5, 2018. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/black-pete.

McBride, Matthew. “Paul Thomas Harris.” Accessed October 10, 2018. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/harris-paul-thomas.

Mueller, Max Perry. Race and the Making of the Mormon People. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.5149/northcarolina/9781469636160.001.0001.

Newell, Quincy D. “Jane Elizabeth Manning James.” Accessed October 5, 2018. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/james-jane-elizabeth-manning.

Newell, Quincy D. “The Autobiography and Interview of Jane Elizabeth Manning James.” Journal of Africana Religions 1, no. 2 (2013): 251–91. https://doi.org/10.5325/jafrireli.1.2.0251.

Newell, Quincy D. “What Jane James Saw.” In Directions for Mormon Studies in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Patrick Q. Mason. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2016.

Newell, Quincy D. Your Sister in the Gospel: The Life of Jane Manning James, A Nineteenth Century Black Woman. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199338665.001.0001.

Parshall, Ardis E. “Marie Graves.” https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/graves-marie.

Parshall, Ardis E. “William and Marie Graves: ‘We found the Right Church All Right…’.” Accessed February 1, 2019. http://www.keepapitchinin.org/2018/09/12/william-and-marie-graves-we-found-the-right-church-all-right/.

Parshall, Ardis E. “William Graves.” https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/graves-william.

Parshall, Ardis W. “Elijah A. Banks.” Accessed October 10, 2018. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/banks-elijah-a.

Pew Research Center. “A Portrait of Mormons in the U.S.” July 24, 2009. Accessed May 18, 2019. https://www.pewforum.org/2009/07/24/a-portrait-of-mormons-in-the-us/#3.

Reeve, W. Paul. “Ardella Bickham Magee.” Accessed May 18, 2019. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/magee-ardella-bickham.

Reeve, W. Paul. “Elijah Able.” Accessed October 10, 2018. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/able-elijah.

Reeve, W. Paul. “Elijah R. Ables.” Accessed July 22, 2019. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/ables-elijah-r.

Reeve, W. Paul. “Ernest Moroni Magee.” Accessed May 18, 2019. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/magee-ernest-moroni.

Reeve, W. Paul. “Esther Jane ‘Nettie’ Scott Kirchhoff.” Accessed October 10, 2018. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/kirchhoff-esther-jane-nettie-scott.

Reeve, W. Paul. “Moroni Able.” Accessed May 18, 2019. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/able-moroni.

Reeve, W. Paul. “Samuel Magee.” Accessed May 18, 2019. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/magee-samuel.

Reeve, W. Paul. Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199754076.001.0001.

Reiter, Tonya S. “Edward ‘Ned’ Leggroan.” Accessed May 18, 2019. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/leggroan-edward-ned.

Reiter, Tonya S. “Esther Jane James Leggroan.” Accessed October 10, 2018. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/leggroan-esther-jane-james.

Reiter, Tonya S. “Frances Leggroan Fleming.” Accessed October 10, 2018. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/fleming-frances-leggroan.

Reiter, Tonya S. “Hyrum Leggroan.” Accessed October 10 2018. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/leggroan-hyrum.

Reiter, Tonya S. “Life on the Hill: The Black Farming Families of Mill Creek.” Journal of Mormon History 44, no. 4 (October 2018): 68–89. https://doi.org/10.5406/jmormhist.44.4.0068.

Reiter, Tonya S. “Mildred Bernice Leggroan Ellis.” Accessed October 10, 2018. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/ellis-mildred-bernice-leggroan.

Reiter, Tonya S. “Susan Gray Reed Leggroan.” Accessed May 18, 2019. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/leggroan-susan-gray-reed.

Rust, Val Dean. Radical Origins: Early Mormon Converts and Their Colonial Ancestors. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Saulny, Susan. “Black Mormons and the Politics of Identity.” New York Times, May 22, 2012. Accessed October 5, 2018. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/23/us/for-black-mormons-a-political-choice-like-no-other.html?_r=2&hp&.

Shearer, Tobin Miller. “‘Buttcheek to Buttcheek in the Pew’: Interracial Relationalism in a Mennonite Congregation, 1957-2010.” In Christians and the Color Line: Race and Religion after Divided by Faith, edited by J. Russell Hawkins and Phillip Luke Sinitiere. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199329502.003.0005.

Sistas in Zion. “Jimmy Kimmel Doesn’t Believe There are black Mormons.” October 5, 2012. Accessed 5 October 2018. http://www.sistasinzion.com/2012/10/jimmy-kimmel-doesnt-believe-there-are.html.

Staker, Mark Lyman. Hearken, O Ye People: The Historical Setting of Joseph Smith’s Ohio Revelations. Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2009.

Stark, Rodney, and Roger Finke. Acts of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Stevenson, Russell W. “‘A Negro Preacher’: The Worlds of Elijah Ables.” Journal of Mormon History 39 (Spring 2013). https://www.jstor.org/stable/24243899.

Stevenson, Russell W. Black Mormon: The Story of Elijah Ables. Afton, Wyoming: PrintStar, 2013.

Stevenson, Russell W. For the Cause of Righteousness: A Global History of Blacks and Mormonism, 1830-2013. Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2014.

Strickling, Laura Rutter. On Fire in Baltimore: Black Mormon Women and Conversion in a Raging City. Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2018.

Stuart, Joseph R. “Len Hope.” Accessed October 10, 2018. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/hope-len.

Stuart, Joseph R. “Mary Lee Pugh Hope.” Accessed October 10, 2018. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/hope-mary-lee-pugh.

Williams, Jessica. “The Black Mormon Vote.” October 9, 2012. Accessed October 5, 2018. http://www.cc.com/video-clips/auxb75/the-daily-show-with-jon-stewart-the-black-mormon-vote.

Notes

-

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is the official name of the church. Its adherents are sometimes referred to as Mormons, a nicknamed derived from the Book of Mormon, a book accepted as scripture by members of the faith. Members are also sometimes called Latter-day Saints, LDS, or Saints, (a term used to mean a follower of Jesus Christ, not to indicate a holy status as in the Catholic tradition). Mormon, Latter-day Saint, and Saint are used interchangeably in this essay. ↩

-

Williams, “Black Mormon Vote.” ↩

-

Saulny, “Black Mormons.” See the embedded video “TimesCast Politics: Black Mormons.” ↩

-

Sistas in Zion, “Jimmy Kimmel.” ↩

-

A July 24, 2009 Pew Research Center survey, “A Portrait of Mormons in the U.S.” found that between one and three percent of U.S. Mormons were black (60,000 to 180,000 members). Dr. Jacob Rugh at Brigham Young University estimates that in 2018 there were one million black Latter-day Saints globally. ↩

-

McBride, “Black Pete.” See also Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 1–8, 64–65. ↩

-

For a history of this process in context see Reeve, Religion of a Different Color. ↩

-

Century of Black Mormons traces thirteen metadata categories in each biography: name, gender, birthdate, birth place, death date, death place, residences (to track mobility over time), baptism, confirmation, faith transition (if a person transitioned to a different faith after joining Mormonism), priesthood (if a man was ordained to the lay LDS priesthood before 1978), and temple (if a man or woman received temple rituals before 1978). ↩

-

See Bailey, Down in the Valley and Glaude, African American Religion for studies that complicate notions of a monolithic “black church.” See Cressler, Authentically Black; Boles, “Dividing the Faith”; Boles, “African American Experiences,” 310–323; Johnson, “Healing the Mystical Body”; and Shearer, “‘Buttcheek to Buttcheek’” for studies that examine racial integration in predominantly white churches. ↩

-

Scholars of Protestantism meanwhile continue to note that “the old adage about eleven o’clock Sunday morning being the most segregated hour in the United States remains true.” See Hawkins and Sinitiere, Christians and the Color Line, 2; and Emerson and Smith, Divided by Faith. The publication of Divided by Faith highlighted the ways in which evangelical Christianity “actually exacerbated” racial divisions in the United States rather than acting to overcome them. ↩

-

See Reeve, Religion of a Different Color; Bringhurst, Saints, Slaves, & Blacks; Stevenson, For the Cause of Righteousness; Harris and Bringhurst, The Mormon Church and Blacks; Mauss, All Abraham’s Children; and Mueller, Race and the Making of the Mormon People. There are exceptions which tend to focus on the two most well documented black Latter-day Saints, Jane Manning James and Elijah Able. See for example, Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel; Newell, “What Jane James Saw”; Newell, “Autobiography and Interview,” 251–91; Coleman, “‘Is There No Blessing for Me?’”; Stevenson, “‘A Negro Preacher’”; Stevenson, Black Mormon; and Jackson, Elijah Abel. ↩

-

For scholarship which examines black LDS worship see Driggs, “’How Do Things Look on the Ground?”; Embry, “Speaking for Themselves,” 99–110; Embry, Black Saints; and Strickling, On Fire in Baltimore. ↩

-

Not all membership records in the database contain such notations and as a result whatever the total number of black Latter-day Saints we ultimately count in the database (expectations are somewhere between 300 and 400) it will automatically be an underrepresentation. ↩

-

On conversion networks see Stark and Finke, Acts of Faith, chapter 5; Allison, “Layered Lives,” 168–213; and Rust, Radical Origins. ↩

-

Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel; Newell, “Autobiography and Interview,” 251–291. See also Newell, “Jane Elizabeth Manning James.” ↩

-

Marie Graves to Heber J. Grant, 10 November 1920, as quoted in Parshall, “Marie and William Graves.” ↩

-

The biographies for William Graves and Marie Graves will be added to the site soon. See also Parshall, “William and Marie Graves.” ↩

-

Reeve, “Esther Jane ‘Nettie’ Scott Kirchhoff.” ↩

-

Parshall, “Elijah Banks.” ↩

-

Reiter, “Esther Jane James Leggroan.” ↩

-

Reiter, “Frances Leggroan Fleming.” ↩

-

The fourteen are Elijah Able, Marie Graves, Marinda Redd Bankhead, Thelma Leggroan Duffy, Frances Leggroan Fleming, Paul Thomas Harris, Len Hope, Mary Lee Pugh Hope, Jane Manning James, Alice Weaver Boozer Leggroan, Esther Jane James Leggroan, Henry Alexander Leggroan, Sarah Ann Leggroan, and Nelson Holder Ritchie. ↩

-

McBride, “Paul Thomas Harris.” ↩

-

Stuart, “Len Hope”; Stuart, “Mary Lee Pugh Hope.” ↩

-

Reiter, “Susan Gray Reed Leggroan”; Reiter, “Edward ‘Ned’ Leggroan.” ↩

-

This included two of Samuel and Ardella’s grandchildren who were baptized in 1936, and are therefore not included in the database. Reeve, “Samuel Magee”; Reeve, “Ardella Bickham Magee.” ↩

-

Reeve, “Ernest Moroni Magee.” ↩

-

Reiter, “Life on the Hill,” 68–89. ↩

-

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, image 550 and 578. ↩

-

Reeve, “Elijah R. Ables”; Reeve, “Elijah Able”; Reeve, “Moroni Able.” The biographies for ArLene Able and other Able descendants are forthcoming. ↩

-

Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel. ↩

-

See Reiter, “Hyrum Leggroan,” for a fourth generation descendant of James and Reiter, “Mildred Bernice Leggroan Ellis,” for a fifth generation descendant. For additional insights on kinship networks among black converts see Reiter, “Life on the Hill.” ↩

Author

W. Paul Reeve,

Department of History, University of Utah, paul.reeve@utah.edu,