Improving Lynching Inventories with Local Newspapers

Racial Terror in Virginia, 1877-1927

Abstract

Lynching inventories are key instruments to gauge the extent of racialized terrorism against African Americans during the post-Reconstruction era in the US South. As Ida B. Wells famously wrote, lynching was not “the creature of an hour, the sudden outburst of uncontrolled fury, or the unspeakable brutality of an insane mob.”1 Instead, lynching was a formidable institution to preserve white supremacy in the Jim Crow South through the systematic use of racial terror. While a small number of lynching victims were white, lynching was a form of state-sanctioned terrorism against African Americans throughout the South.2 Some lynch mobs operated in disguise, while many others did not bother to conceal their identities. Prominent citizens, and even local authorities, often participated in the macabre ritual of killing alleged criminals in the name of “justice,” race, or tradition. Very few lynchers ever faced trial, and even fewer were indicted for their crimes. The expectation of impunity for this kind of extralegal violence underscores the complicity of local, state and federal authorities in perpetuating a state of racial terror for African Americans during Jim Crow.

The digital history project Racial Terror: Lynchings in Virginia, 1877–1927 compiles an amended and enhanced inventory of lethal mob violence in Virginia. Starting from the Beck-Tolnay3 inventory of Southern lynchings, this project, for the first time, uses local Virginia newspapers rather than national newspapers, as its main source of information. Critically, this project unveils how white victims of lynching in Virginia have been overcounted in the past. This is an important finding because lynching apologists in the South (and sometimes in the North) often used white lynching victims to defend lethal mob violence. Rather than a tool of white domination, apologists would argue, lynching was a legitimate and non-racialized enforcement of “popular justice” against hideous crimes. The overestimation of white lynching victims further reinforces our understanding of the lynching era as one of racialized terror. Local newspapers and archives are vital sources to correct existing catalogues.

Lynching Definition and Catalogues

To understand the pervasiveness of lynching in the South, it is essential to measure how many lynchings took place and who were the victims of lethal mob violence. A shared definition of what constitutes a lynching is necessary to provide a consistent measurement of racial terror in the South. It was only in 1940 that a consensus definition was reached at a NAACP meeting at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama with other anti-lynching organizations. According to this definition, lynching involves the extra-legal killing of a person by a group of at least three people acting under the pretext of service to justice or tradition.4 While this definition has its limitations,5 scholars widely accept it and have adopted it for research purposes.

Historically, three primary sources have been used to count lynching: (1) the Tuskegee Institute’s national inventory of more than 4,700 lynchings between 1882 and 1964; (2) the NAACP database, covering the years from 1889 to the 1950s; and (3) the Chicago Tribune’s yearly recording of lynching victims between 1882 and 1918.6 All of these sources contain several errors and tend to be inconsistent, often leading contemporary scholars to compile their own inventories that focus on different geographical areas and historical periods.7 These updated inventories are used to assess the extent, causes, and consequences of lethal mob violence in the United States. In addition to supplying critical information about the circumstances surrounding lynchings, catalogues allow the computation of temporal patterns and the geographical distribution of lethal mob violence.

The most comprehensive effort to document lynchings in the US South is the Beck-Tolnay inventory, available at the CSDE Lynching Database website, covering 1882–1930. Starting from the three historical inventories (Tuskegee, NAACP, and Chicago Tribune), Beck and Tolnay verified each reported lynching for ten Southern states (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee), using a mix of national and local newspapers as their main source of information.8 They also conducted additional newspaper research to identify other lynching cases. More recently, Beck expanded the database by identifying victims of mob violence in Virginia and West Virginia.

The Racial Terror project revisits and complements the Beck-Tolnay inventory of Virginia lynchings by using local Virginia historical newspapers, rather than national ones. Typically, researchers have relied on national newspapers to compile lynching databases;9 however, local newspapers often reported more detailed accounts of lynching, due to their geographical proximity to the events and easier access to local sources. Local newspapers also were more likely to follow up on local stories and cover the aftermath of a lynching.

Racial Terror Project

In the spring of 2017, I led a research team of six senior students enrolled in an advanced research course at James Madison University. Their semester-long task was to verify each Virginia lynching victim contained in the Beck-Tolnay database. Relying on the Chronicling America website, students searched, catalogued and compiled a database of historical Virginia newspapers.10 In early 2018, the database was made publicly available through the Racial Terror: Lynching in Virginia, 1877–1927 website. This site tells the stories of the 104 known Virginia lynching victims between the end of Reconstruction and the introduction of the Virginia Anti-lynching Law in 1928.11 Thanks to this original research on local newspapers, the website provides a revised and more detailed catalogue of Virginia lynchings, adding information on the age and the occupation of each lynching victim, as well as more precise geographical information (town/city) regarding the location of the lynching, whenever available. Furthermore, local newspapers helped to identify one previously unnamed lynching victim.12

The unique advantage of using a digital history project to revise the lynching database lies in its openness, iterative nature and replicability.13 As more historical newspapers are digitized, the inventory gets periodically updated and expanded. Website users routinely comment on the project, provide feedback and submit additional information to enrich the website, or correct errors.14 In addition to its research objective, this digital project also includes civic and pedagogical aspirations; in particular, it strives to help restore the collective memory of lynching victims, too often erased from local histories. Thus, for each lynching victim, the Racial Terror website dedicates a page detailing the events leading to their killing and what happened afterwards; it also displays all the primary sources (local newspapers) used to reconstruct that story. Making this material available online invites local communities and activists to conduct their own research and engage with the history of racial terror in their localities. An interactive map of Virginia (see figure 1) visually displays where each lynching occurred.

The website also provides a searchable database of more than 500 historical Virginia newspaper articles on lynching. The articles are drawn from 36 local newspapers (except for three articles coming from The Washington Post and one from the New York Tribune).15 The Alexandria Gazette is the newspaper with the largest number of articles (99), followed by the Richmond Dispatch (84) and The Richmond Times (55). Almost all of the news articles come from white mainstream newspapers, with the important exception of 53 articles from the Richmond Planet, one of the most vociferous anti-lynching black newspapers.16

Local Newspapers and Overcounting Lynching Victims

The main methodological innovation of this project lies in the use of local Virginia newspapers to verify the existing inventory and collect additional information about the events preceding the killing, as well as its aftermath. Local newspapers in the late 1800s and early 1900s usually covered one or two counties and targeted a localized audience with a preponderance of local stories over state-wide and national ones. Local newspapers in large cities, like Richmond, had a more regional appeal and wider readership, but they still retained a keen interest in reporting about important local stories like lynching. These newspapers would often reprint dispatches from local outlets about mob violence and were also more likely than national newspapers to cover the legal/political consequences of a local lynching.

Local newspapers can thus improve existing lynching inventories, which are based mainly on national newspapers that typically underestimate lethal mob violence.17 Lynchings reported locally, for instance, may not have been picked up by a national news service, or larger regional newspapers.18 If that is the case, a lynching would not appear in the inventory. Searching for unreported lynchings is a key challenge for scholars and activists, and historiography has extensively examined the issue of undercounting lynching victims.19

Rarely discussed, however, is the issue of overcounting, that is “the reporting of events that were not really lynchings.”20 Tolnay and Beck warned that the “problem of overcounting in previous lynching inventories is as potentially serious as that of undercounting.” Overcounting can be ascribed to the reliance on national newspapers, as well as activist groups’ advocacy against lynching. For instance, Cook claims that the NAACP probably overcounted (black) lynching victims to dramatize the atrocity of mob violence.21 Noticing that the NAACP overcounted lynching victims in the Mid-Atlantic, Barrow instead attributed this over-reporting to the NAACP’s reliance on national newspapers.22 This project expands this under-researched historiography by confirming that overcounting is indeed as much of a problem as undercounting. Remarkably though, overcounting concerned only white victims in Virginia, raising several questions as to how to interpret and correct current lynching inventories.

The Beck-Tolnay inventory identified 109 lynching victims in Virginia between 1877 and 1927. Eighty-three victims were black (76% of the total number of victims), one of them, Charlotte Harris, a woman; the remaining 26 victims were white (24%), one of them, Peb Falls, a woman. Researching local Virginia newspapers, however, uncovered that six of the alleged victims were not lynched after all. These six non-victims were all white men.

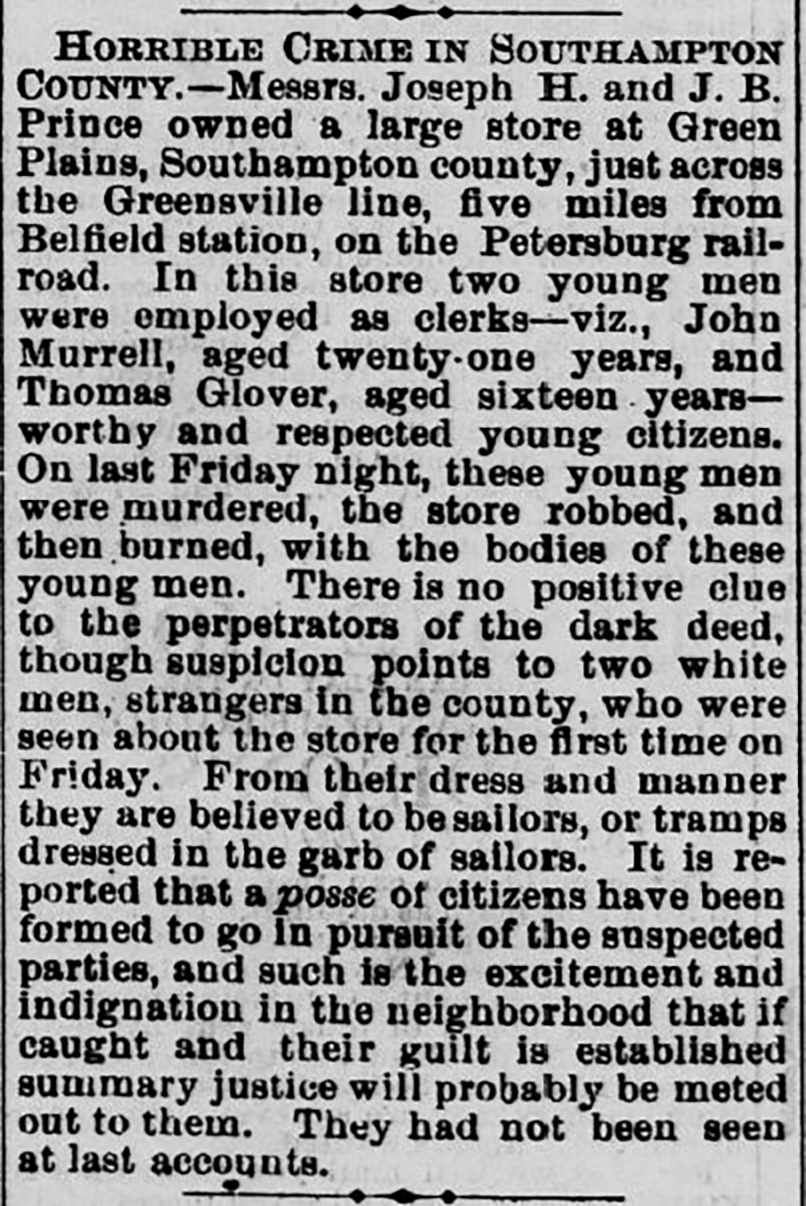

The Beck-Tolnay inventory listed two white brothers, J. B. Prince and J. H. Prince, killed when a mob burned down a store on December 26th, 1881 in Green Plains, Southampton County. The Prince brothers, however, were merely the owners of the store. The article from the Staunton Spectator shown in figure 2 reported that two young clerks, John Murrell and Thomas Glover, perished because of the fire, but this was not the result of a lynching mob.

While there were rumors of a possible lynching for the perpetrators of the arson (not of the Prince brothers), no further information has been found regarding this event.

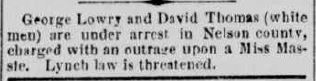

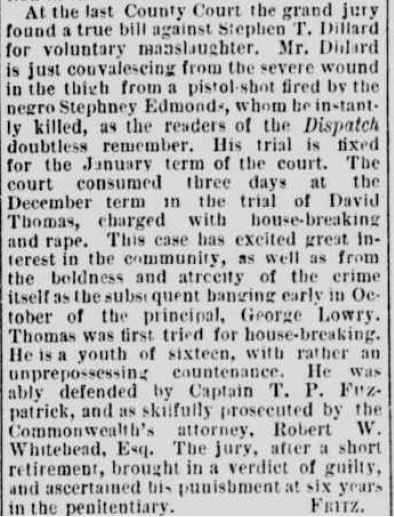

Both Brundage and the Beck-Tolnay inventory indicated David Thomas, a 16-year-old white youth, as a victim of a double lynching that allegedly took place on October 8th, 1880 in Nelson county. Thomas and his brother-in-law George Lowry (also white) were accused of robbery and attempting an outrage on a young white woman.

After their arrest, a mob seized Lowry from the Nelson county jail and hung him to a nearby oak tree (Alexandria Gazette). However, the Daily Dispatch of Richmond reported that the mob only lynched Lowry and spared the young Thomas. A few months later, Thomas was tried and sentenced to six years in prison for robbery.

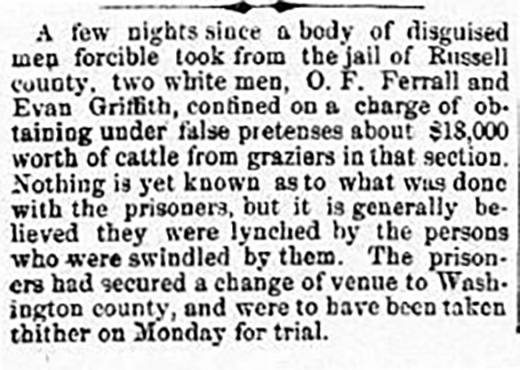

Two white men, Evan Griffith and O. F. Ferrall, were accused of cattle theft by deception and allegedly lynched in Russell County on January 22nd, 1883, as per the Beck-Tolnay inventory. The Alexandria Gazette partially confirmed this story on January 25th.

However, a few days later, both the Daily Dispatch and the Shenandoah Herald reported that a mob dragged Ferrall and Griffith from jail and took them into the nearby woods; upon the “exhibition of ropes and threats of hanging”, the two men “disgorge(d)” the $18,000 they had stolen, thus eschewing the lynching mob (Daily Dispatch).

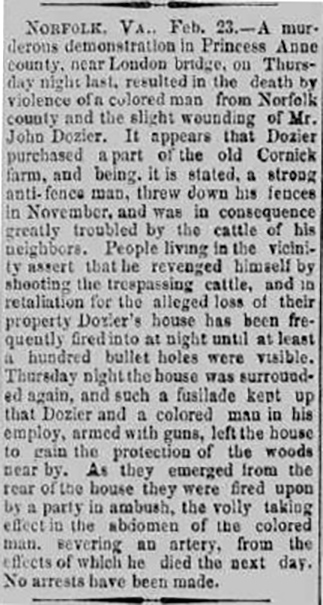

In addition to revealing these cases where five white men were either erroneously reported as lynching victims, or able to escape the mob, local newspapers were instrumental in correcting the record regarding another alleged white lynching victim: John Dozier. A white farmer, Dozier was reported as lynched by his neighbors in 1880 in Norfolk County; instead, it was his employee, an unnamed African American man, that was killed. Infuriated about his neighbor’s cattle trespassing on his property, Dozier “revenged himself by shooting the trespassing cattle” (Shenandoah Herald). On the night of February 19th, 1880, the cattle owners retaliated by firing at least 100 bullets into his home. As Dozier and his employee, an African American man, ran towards the woods trying to take cover, the neighbors kept shooting at them, slightly wounding Dozier. His employee, however, was shot in the abdomen and died the next day. No one was immediately arrested, and it is unknown if any legal action was taken afterwards against the lynchers.

Thanks to this new research based on local newspapers, the revised inventory lists 83 black men (79%), one black woman, one white woman and 19 white men (18%) as lynched in Virginia between 1877 and 1927.23 All six cases of overcounting are concentrated in a relatively short temporal span (between 1880 and 1883); however, it would be difficult to connect overcounting to a certain newspaper or region, as the numbers involved here are too small. Aside from all being white newspapers, there is little in common across them in terms of their attitude towards lynching, readership or geographical location. Mundane news routine constraints (e.g., getting correct information and writing under strict deadlines) are probably the best explanations for these idiosyncrasies.

Correcting the record

The Racial Terror database unveils that 1 in 5 lynching victims in Virginia were white, and not 1 in 4 as previously reported. Why were white victims overcounted in Virginia? One possible explanation relates to how national newspapers in the South, but also for a certain time in the North, used the lynching of white men as a justification for lethal mob violence. In fact, these lynchings were used as “proof” that all criminals, and not just black men, were the target of “popular justice”. Mob violence might be at times unwarranted, but it had little to do with race; instead, lynching was an understandable, if sometimes regrettable, answer to atrocious crimes that a weak and ineffective criminal justice system was unable to handle properly.24 Differently from the obsessive coverage of the lynching of “black brutes,” white lynching victims were simply fodder to justify lethal mob violence. Once these stories of white lynching victims were published, national newspapers had few resources or incentives to follow up on them, let alone correct the record of white lynchings.25 Local newspapers, on the other hand, were more likely to keep covering these localized events, and thus more likely to correct eventual misreporting.26

The overcounting of white victims in Virginia raises the question of whether this was just a Virginia oddity, or a more general methodological issue concerning inventories based on national newspapers. Only systematic research using local newspapers and archives in each state can address this question.27 Would this pattern be confirmed, it would suggest that the lynching of white victims was even less common than previously imagined, further corroborating the racialized nature of lethal mob violence in the South as an instrument of white supremacy. Researching local newspapers and archives should thus be part of any strategy to confirm the actual occurrence of a lynching, especially as scholars strive to compile a unified national lynching database.28 Ultimately, local newspapers enrich the information about the circumstances of each lynching, enhancing our understanding of how racialized terrorism came to define the Jim Crow South. Digital history projects that make this information readily available to the public and researchers advance this goal through its open nature and engagement with local knowledge and communities.

Bibliography

Barrow, Janice Hittinger. “Lynching in the Mid‐Atlantic, 1882–1940.” American Nineteenth Century History 6, no. 3 (2005): 241–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664650500380969.

Bailey, Amy Kate, and Stewart E. Tolnay. Lynched: The Victims of Southern Mob Violence. Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books, 2015.

Berg, Manfred. Popular Justice: A History of Lynching in America. Lanham MD: Ivan R. Dee, 2011.

Beck, E. M., and Stewart E. Tolnay. “Confirmed inventory of Southern lynch victims, 1882–1930.” Machine-readable data set, 2016. Available from authors.

Brundage, Fitzhugh. Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880–1930. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

Cook, Lisa D. “Converging to a National Lynching Database: Recent Developments and the Way Forward.” Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 45, no. 2 (2012): 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/01615440.2011.639289.

Perloff, Richard M. “The Press and Lynchings of African Americans.” Journal of Black Studies 30, no. 2 (2000): 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/002193470003000303.

Seguin, Charles, and David Rigby. “National Crimes: A New National Data Set of Lynchings in the United States, 1883 to 1941.” Socius 5 (2019): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023119841780 .

Smith, J. Douglas. Managing White Supremacy: Race, Politics, and Citizenship in Jim Crow Virginia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Tolnay, Stewart E., and E. M. Beck. A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings, 1882-1930. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1995.

Trotti, Michael Ayers. “What counts: Trends in Racial Violence in the Postbellum South.” The Journal of American History 100, no. 2 (2013): 375–400. https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jat286.

Wells, Ida B. “Lynch law in America.” The Arena 23 (1900): 15–24.

Notes

-

Wells, “Lynch Law in America,” 15. ↩

-

Tolnay and Beck, A Festival of Violence, 19. ↩

-

Beck and Tolnay. “Confirmed inventory of Southern lynch victims.” ↩

-

Bailey and Tolnay, Lynched, 3. ↩

-

For instance, the exact number of participants in a lynching might be unknown and posses were sometimes legally deputized by local authorities. In other cases, information about mob motives might be ambiguous. See Bailey and Tolnay, Lynched, 4. ↩

-

Bailey and Tolnay, Lynched, 5. ↩

-

For an overview of existing catalogues, see: Cook, “Converging to a National Lynching Database.” ↩

-

Tolnay and Beck, A Festival of Violence, 259–263 ↩

-

Cook, “Converging to a National Lynching Database,” 57. ↩

-

Students used advanced search tools to find articles about each lynching victim relying on the information contained in the Beck-Tolnay database. Data on victim name, county, accusation or method of execution, were used as keywords, as well as more advanced search techniques. Students inspected newspapers around the date of the lynching, as well as few months before—to reconstruct the events leading to the lynching—and after the killing itself, to collect information about the aftermath. Additional research was conducted using the Newspaper Archive depository. ↩

-

Smith, Managing White Supremacy, 155–88. The website has recently been updated with additional victims from the 1860s and 1870s. ↩

-

Philip Mabry (or Mobry) was allegedly part of a group of African American men who killed a white dentist in Mecklenburg County in 1890. According to the Evening Star, on the night of December 24th, 1890, Philip Mabry “was taken from the jail at Boydton by a large body of masked men and lynched.” Other reports suggest that two other black men accused of the murder of the white dentist were later lynched, but these additional lynchings have not yet been confirmed. ↩

-

For a similar digital project on lynching in North Carolina and South Carolina, see A Red Record: Revealing Lynchings in North Carolina and South Carolina. ↩

-

For instance, the inventory now includes the 1932 lynching of Shedrick Thompson in Fauquier County, thanks to the original research generously provided by author and journalist Jim Hall. ↩

-

The articles are organized in a relational database that allows readers to browse, search, access and download the newspaper pages. The database is constantly updated as more newspaper articles are added to the website. ↩

-

Brundage, Lynching in the New South. It is beyond the scope of this paper to compare systematically how white and black newspapers covered lynching in Virginia, a surprisingly under-researched area of scholarship. See Perloff, “The Press and Lynchings of African Americans,” 315–330. ↩

-

One of the few exceptions is Brundage, Lynching in the New South, 296–299. According to Brundage’s catalogue, 86 people were lynched in Virginia between 1880 and 1927, 70 of them black, 16 white. This inventory, however, is also partially outdated. ↩

-

Tolnay and Beck, A Festival of Violence, 262. ↩

-

Trotti, “What Counts,” 375–400. ↩

-

Tolnay and Beck, A Festival of Violence, 262. ↩

-

Cook, “Converging to a National Lynching Database,” 51. ↩

-

Barrow, “Lynching in the Mid‐Atlantic,” 265. ↩

-

Like any other lynching database, this is not a definitive list of victims. The updated inventory of Virginia lynching victims can be consulted on the project website. ↩

-

Brundage, Lynching in the New South, 86. ↩

-

Except for ‘unwarranted’ lynchings, especially of high-status white victims, or sensational cases like the lynching of Leo Frank in Georgia in 1915: Berg, Popular Justice. ↩

-

To be sure, local newspapers also share some of the limitations of the national press in covering lynchings, and a more complete research strategy would require the use of local archives and oral histories. ↩

-

Barrow, “Lynching in the Mid-Atlantic,” 265. ↩

-

Cook, “Converging to a National Lynching Database,” 61. See also Seguin and Rigby, “National Crimes.” ↩

Author

Gianluca De Fazio,

Department of Justice Studies, James Madison University, defazigx@jmu.edu,