Mapping Black Ecologies

Abstract

This essay is our first effort in a long-term collective project organized to collect historical and contemporary narratives from Black communities that offer alternative epistemic entry points for historicizing and interrupting mounting ecological crisis. We use the space of this essay to lay the conceptual groundwork for this collaborative effort (which has not yet materialized a website) through our primary concept, Black ecologies.1 On the one hand, this idea provides a way of historicizing and analyzing the ongoing reality that Black communities in the US South and in the wider African Diaspora are most susceptible to the effects of climate change, including rising sea levels, subsidence, sinking land, as well as the ongoing effects of toxic stewardship. On the other hand, Black ecologies names the corpus of insurgent knowledge produced by these same communities, which we hold to have bearing on how we should historicize the current crisis and how we conceive of futures outside of destruction.

On October 11, 2018, social media began to be inundated with posts form rural communities throughout Central and Tidewater Virginia. Many reported that wind and rain had begun to pick up around their houses. Although this batch of storms was anticipated by weather forecasters as part of the movement northward of hurricane and then tropical storm Michael, the terror of these storms was not diminished for many of the people in the region. Within the three years since February 2015 when a cell destroyed a 150-year old Black Church, St. John’s Baptist of Desha, Virginia, and a number of homes in Essex County as well as across the Rappahannock River in Naylor’s Beach, people in rural Tidewater Virginia have been terrified by the prospects of these violent storms. Virginians, especially those in vulnerable rural communities, have already had to define a new normal based on the likelihood of destructive weather because of the changing climate.

At least five tornadoes were later identified as having touched down across the state. The above footage shot by Sherita Mahone of Middlesex County, Virginia shows a large tree toppled near her home. She along with many of the residents of the area remained without power for several days. Her clip maps infrastructural vulnerability for people inhabiting the scarps and terraces of the Tidewater. She is, like the many registering fear on social media as the storms approached, an active cartographer of the overlapping ecological and social susceptibility that defines life for Black communities in the region and beyond. Both rural and urban Black communities in the Tidewater of Virginia and Southern Louisiana, for example, are particularly vulnerable to rising water and the intensification of acute weather events. Inhabiting low lying land, disproportionately in mobile homes and other vulnerable structures, and often situated in bayous, wetlands, and clearings between groves of soft and easily wind-toppled pine trees on the cheapest land, working-class Black Southerners face immediate danger in weather events exacerbated by climate change as well as the long-term effects of coastal subsidence and the rising water table.

Events of environmental catastrophe lay bare the core dimensions of the social sphere in which they occur. Both Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Harvey exposed the matrix of inequality that existed along the United States’ Gulf Coast and in the Tidewater of Virginia. As geographers Katherine McKittrick and Clyde Woods explain, these storms “brought into clear focus, at least momentarily, a legacy of uneven geographies, of those locations long occupied by les damnés de la terre/the wretched of the earth: the geographies of the homeless, the jobless, the incarcerated, the invisible laborers, the underdeveloped, the criminalized, the refugee, the kicked about, the impoverished, the abandoned, the unescaped”2. In Katrina’s aftermath, the ideological and physical violence imposed upon Black life was flung into the international spotlight. World news media broadcast images of low income and working-class African Americans, clinging to their rooftops and attics, praying to be rescued from their flooded homes. It is from this international gaze that the world began to become aware of what many in the United States knew already.

A willful distortion of reality is required to suggest that Hurricane Katrina suddenly created the social vulnerability of Black Americans (particularly those living in the US South), as if public policy had not been purposefully divesting from working-class Black communities for decades. This divestment diminished not only the political and economic resources of these communities, but also their ability to withstand events of ecological catastrophe. Within the vortex of media coverage, many Black celebrities used the heightened attention to spread messages about the state’s indifference to the people killed and displaced by Katrina. Songs from rappers Lil’ Wayne and Juvenile, in addition to New Orleans-based independent rappers, levied poignant critiques at not only the federal government and local police response to Hurricane Katrina, but also towards an American civil society that places Black men, women, and children beyond the pale of citizenship or incorporation into the body politic, into a liminal space of raw intergenerational vulnerability. As, Lil’ Wayne maps in his ingenious critique of the Bush Administration’s response to Katrina:

I was born in the boot at the bottom of the map New Orleans baby, now the White House hating Trying to wash us away like we not on the map Wait, have you heard the latest They saying that you gotta have paper if you tryna come back Niggas thinking it’s a wrap See we can’t hustle in they trap, we ain’t from (Georgia) Now it’s them dead bodies, them lost houses

Excuse me if I’m on one And don’t trip if I light one, I walk a tight one They try tell me keep my eyes open My whole city underwater, some people still floatin’ And they wonder why black people still voting ‘Cause your president still choking Take away the football team, the basketball team And all we got is me to represent New Orleans, shit No governor, no help from the mayor Just a steady beating heart and a wish and a prayer

Yeah, Born right here in the USA But, due to tragedy looked on by the whole world as a refugee So accept my emotion Do not take it as an offensive gesture It’s just the epitome of my soul And I must be me We got spirit y’all, we got spirit We got soul y’all, we got soul They don’t want us to see, but we already know

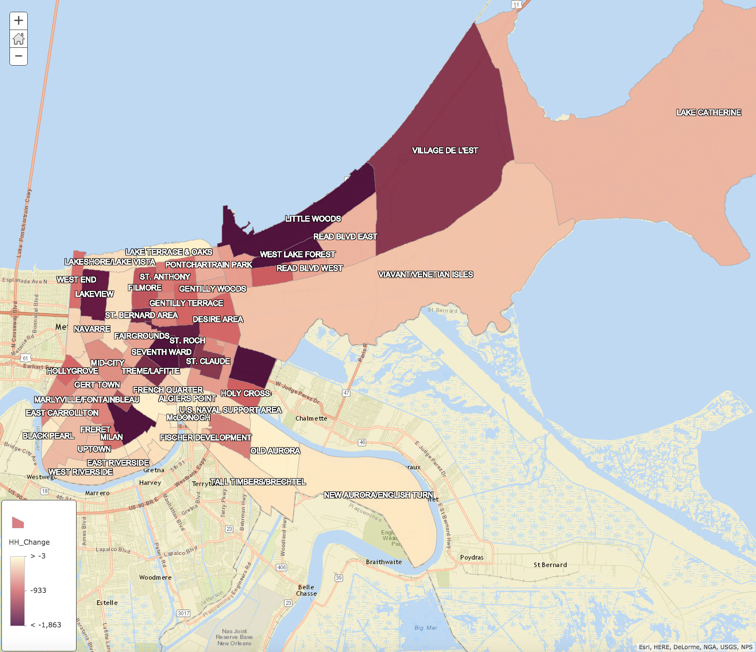

Our ongoing project integrates audio, images, and digital mapping in its analysis, in order to depict the ways that Southern Black communities mobilize against the historical and contemporary struggles of the racial capitalocene—Françoise Vergès’ critical interrogation of the so-called Anthropocene. Vergès mobilizes Cedric Robinson’s concept of racial capitalism and its attendant challenge to the conceptions of capitalism that ignore its originary dependence on racialization to challenge this nascent discourse of the Anthropocene, which in broad strokes paints the mounting ecological crisis in terms of generic, undifferentiated humanity.5 While recognizing the ways that geospatial analysis and digital tools augment and enhance historical interpretation, our ongoing project also reckons with the inherent violence of cartography as a practice. Sylvia Wynter explains how Western cartography developed as a set of technologies and spatial tactics in order to facilitate Western imperialism and its exploitative, genocidal projects.6

Projecting and transforming a multilayered 3D place onto a 2D digital map necessitates the literal and figurative flattening of that location, producing a colonial, “bird’s eye view” of a landscape. This project deals with this contradiction by georeferencing oral history interviews, census demographic maps, and land deeds onto all 2D maps, deepening their historical contexts and infusing the voices of the people who lived in these communities. In Black Atlas: Geography and Flow in Nineteenth-Century African American Literature, Judith Madera argues that “place” is a social construction that is both discursive and affective. Further, she asserts that “counter-cartographies,” or “people’s geographies,” are key ways that Black people have defined spaces for themselves and de-stabilized dominant and exclusionary representations7. Our ongoing project on Black ecologies intervenes from this perspective, incorporating audio, images, and digital mapping in order to create “deep maps” that garner a robust appreciation for both Black ecological vulnerability and possibility from the vantage of these same communities. Often prevented from participating in the production of state recognized cartographic and ecological knowledge due to the political economy of knowledge production in an anti-Black world, this wide-ranging set of sources shows the capaciousness of Black culture, thought, and social life for producing trenchant analyses and critiques of the continuities in the devastation and the possibilities shaping Black living. We argue that these Black counter-cartographies are spatial tactics of resistance. These “people’s geographies” refuse statist claims of irredeemable low income and working-class Black Southern communities that can acceptably be allowed to face the brunt of ecological vulnerability in the United States.

The histories and ongoing experiences of these communities require a robust vision for environmental history, one that refuses to segregate toxic exposure and vulnerability to climate change from the broader political, social, and economic history of Black life and death. Variable exposure to phenomena associated with the defilement of the planet did not emerge with smoke stacks and automobility but rather with the origins of the racial capitalocene in the articulation of the plantation-industrial complex beginning in the colonization of the Americas. Eighteenth-century planters like Landon Carter of Sabine Hall in the Northern Neck of Virginia forced slaves to transfigure the interface of water and land constituting the so-called “golden age” of the Tidewater through the construction of dams, the herding of domesticated animals at the expense of those indigenous to the region, and the displacement of forest biodiversity through the planting of wheat and tobacco. As Carter’s diary illustrates, the effects of these transformations as well as proximity to distant places facilitated through transit routes along the growing Atlantic commerce set off various dislocations and epidemics that were shaped by environmental transformation. Carter reported chronic small-pox epidemics, flies pestilent to wheat “said to be sent into the Country by Mr. John Tucker of Barbadoes [sic],” rampant diarrheal diseases, and fits of ague or malaria overtaking the enslaved as well as his biological family after heavy downpours, likely exacerbated by deforestation. Enslaved, free, and later post-emancipation communities suffered the effects of these transformations as malnourished laborers forced to transform the landscape by filling swamps, rerouting and damning waterways, herding domesticated animals, and clearing forests.8 Ongoing exposure is the legacy of these sedimented histories that form a radical and disturbing continuity in regional and local histories of the United States South and the wider African Diaspora.9

We call for the widened yet elastic concept of “Black ecologies” as a way of mapping ongoing susceptibility as a function of historical and ongoing relations. Like Black geographies, the designation Black marks the outside within the ecologies of living—the spaces that sustain and reproduce normative forms of biological and social existence. As a naming of the outside and the bottom, Black ecologies are foremost sites of ongoing injury, gratuitous harm, and premature death.10 The designation of these as ecologies seeks to bring into focus the critical ways that forces above even the hand of Man punctuate, underline, and exacerbate raw spatial inequality.11 Black ecologies are spaces threatened directly by the rising seas and made toxic as the sites where the byproducts of production and consumption can be dumped.12 At the same time, they form the critical ecologies of the damned, sites wherein ordinary Black people articulate alternative maps—dissonant and heterodox ecological grammars as well as vision for a different order.

Part of the methodological stakes in taking the critical knowledges produced in Black ecologies is the imaginative engagement with heterodox forms they take. This is evidenced in the music of New Orleans-based hip hop and Blues artists that critiqued the state’s response to Hurricane Katrina, and the videos mapping the aftermath of violent storms in Virginia alike. However, Black counter-cartographic knowledge has a much longer genealogy in Black practice and thought. In her 1937 interview with a Works Progress Administration recorder, Minnie Fulkes, a formerly enslaved woman in Virginia recast vulnerability to violent weather as something hopeful—as something that might not just evade but eliminate into the stillness of death the power of white supremacy in shaping the anti-Black landscape she understood as having originated in slavery. After describing violence on plantations and the ongoing economic exploitation Black people faced in the 1930s, Fulkes told her interviewer quite candidly, “Lord, Lord, I hate white people and de flood waters gwine drown some mo.”13 Here Fulkes’ cartographic knowledge of a water landscape from the bottom is recast not simply as vulnerability but as a subtle demand on her god to eradicate the white powerholders benefitting from the uneven contours perpetuating relations originating in slavery through the landscape.

As political scientist Michael Hanchard posits, “Black memory is often at odds with state memory.” Examining Black ecologies draws to light the environmental history sedimented in ongoing unequal exposure but also reveals insurgent visions of an environmental future free of the relations and geographies engendered by the racial capitalocene. These visions depart from mainstream environmental discourses that privilege conservation and preservation without critically analyzing the ways these conceptions maintain the dominant subject-object relations of mastery and draw directly on the history of imperial management. Instead, they draw on a more liberatory vision for freeing the land and the people available through our paradigm of Black ecologies.

Bibliography

Commission for Racial Justice. “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States: A National Report on the Racial and Socio-Economic characteristics of Communities with Hazardous Waste Sites.” New York: United Church of Christ, 1987.

Federal Writers’ Project. Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves. Federal Writer’s Project. Library of Congress. https://lccn.loc.gov/41021619.

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. “Fatal Couplings of Power and Difference: Notes on Racism and Geography.” The Professional Geographer 54, no. 1 (2002): 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-0124.00310.

Greene, Jack P., ed. The Diary of Colonel Landon Carter of Sabine Hall, 1752–1778. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1965.

Hanchard, Michael. “Black Memory versus State Memory: Notes toward a Method.” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (June 2008): 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1215/-12-2-45.

Hare, Nathan. “Black Ecology.” The Black Scholar 1, no. 6 (2016): 2–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.1970.11728700.

Hartman, Saidiya. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Lil’ Wayne feat. Robin Thicke. “Georgia Bush.” Dedication 2. 2006.

Lil’ Wayne feat. Robin Thicke. “Tie My Hands.” The Carter III. Cash Money Records: 2008.

Madera, Judith. Black Atlas: Geography and Flow in Nineteenth-Century African American Literature. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015.

McKittrick, Katherine, and Clyde Woods. Black Geographies and the Politics of Place. Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2007.

Pulido, Laura. “Rethinking Environmental Racism: White Privilege and Urban Development in Southern California.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90, no. 1 (March 2000): 12–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/0004-5608.00182.

Roane, J.T. “Plotting the Black Commons.” Souls Journal 20, no. 3 (2019): 239–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999949.2018.1532757.

Roane, J.T. “The Loss of Sanctuary; The Loss of Community: Climate Change in the Era of Black Lives Matter.” New Black Man in Exile blog (February 26, 2016). https://www.newblackmaninexile.net/2016/02/reflections-on-tornado-that-destroyed.html.

Robinson, Cedric. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Vergès, Françoise. “Racial Capitalocene.” In Futures of Black Radicalism, edited by Theresa Gaye Johnson and Alex Lubin. Brooklyn: Verso, 2017.

Wynter, Sylvia. “1492: A New World View.” In Race, Discourse, and the Origin of the Americas: A New World View, edited by Vera Lawrence Hyatt and Rex Nettleford. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995.

Yusoff, Kathryn. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Notes

-

We build on the effort of Nathan Hare to understand the overlapping social, economic, and ecological vulnerabilities defining Black life. See Hare, “Black Ecology.” ↩

-

McKittrick and Woods, Black Geographies and the Politics of Place, 2. ↩

-

Lil’ Wayne and Robin Thicke, “Georgia…Bush/Weezy’z Ambitionz.” ↩

-

Lil’ Wayne and Robin Thicke, “Tie My Hands.” ↩

-

Vergès, “Racial Capitalocene;” Robinson, Black Marxism; Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes. ↩

-

Wynter, “1492: A New World View.” ↩

-

Madera, Black Atlas: Geography and Flow, 1–23. ↩

-

Greene, The Diary of Colonel Landon Carter of Sabine Hall, 127–200. ↩

-

Roane, “Plotting the Black Commons,” 239–266. ↩

-

Gilmore, “Fatal Couplings of Power and Difference: Notes on Racism and Geography,” 15–24; Hartman, Scenes of Subjection. ↩

-

Pulido, “Rethinking Environmental Racism,” 12-40. ↩

-

United Church of Christ, “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States.” ↩

-

Minnie Fulkes interviewed by Susie Byrd, in Federal Writers’ Project Slave Narratives, Vol. XVII. ↩

Authors

J.T. Roane,

Department of Africana Studies, Arizona State University, jtroane@asu.edu,