Black Placemaking in Texas

Sonic and Social Histories of Newton and Jasper County Freedom Colonies

Abstract

Heritage is spatial, because it asks us to consider where something occurred and why it happened there. Historical designation policies are based on officially accepted theories of historical significance, social location, and collective identities. Regulatory frameworks, architectural and archaeological expertise, and social assumptions about which places matter inform decisions about which sites are designated as “historical” and worthy of specific land use protections. Official processes, documentation and designation can create homogenized histories that remove differences, conflicts, and complexities.1 For example, Texas freedom colony settlement formation and dispersal are consequences of multiple spatialized heritages rooted in slavery, emancipation, and resistance against racial terrorism and Jim Crow laws. Thus heritage and public history, especially that informed by racialized regulatory regimes, become powerful mediums through which the significance of identity and place are mediated. This study of freedom colonies (FCs) and the subsequent development of an online Atlas based on its findings is one approach to reclaiming histories of Black agency in the landscape from official heritage mediators who control what Laurajane Smith calls Authorized Heritage Discourse.2

Freedom colonies are historic African American settlements founded after the Civil War in Texas. From 1865 to 1920, African Americans founded at least 557 self-sustaining FCs (also known as Black Settlements and Freedmen’s Towns) in Texas. Freedom colonies notably reflect a trend in precipitous increases in Black land ownership during Reconstruction and Progressive Eras. For instance, Black Texans went from owning 1.8% of Texas farmland in 1870 (839) to 26% (12,513) in 1890.3 By 1900, African Americans represented 31% of rural landowners in Texas.4 Freedom colonies are where these clusters of landowners lived.

These rural Texas landscapes, historically associated with exclusion and even hate crimes,5 are simultaneously under-recognized and unprotected sites holding evidence of Black freedom-seeking articulated through placemaking. For example, Huff Creek, in Jasper County, (depicted in Figure 1) was a little known freedom colony. The 1998 dragging death of James Byrd, which took place on the community’s main road, overshadowed the existence of the freedom colony in the public imagination. Instead, popular culture considers the City of Jasper the site of the crime rather than unincorporated Huff Creek. FCs are also particularly vulnerable to natural disasters, absent from public planning records, and lack access to the funding and technical assistance afforded incorporated, urbanized, mapped places.

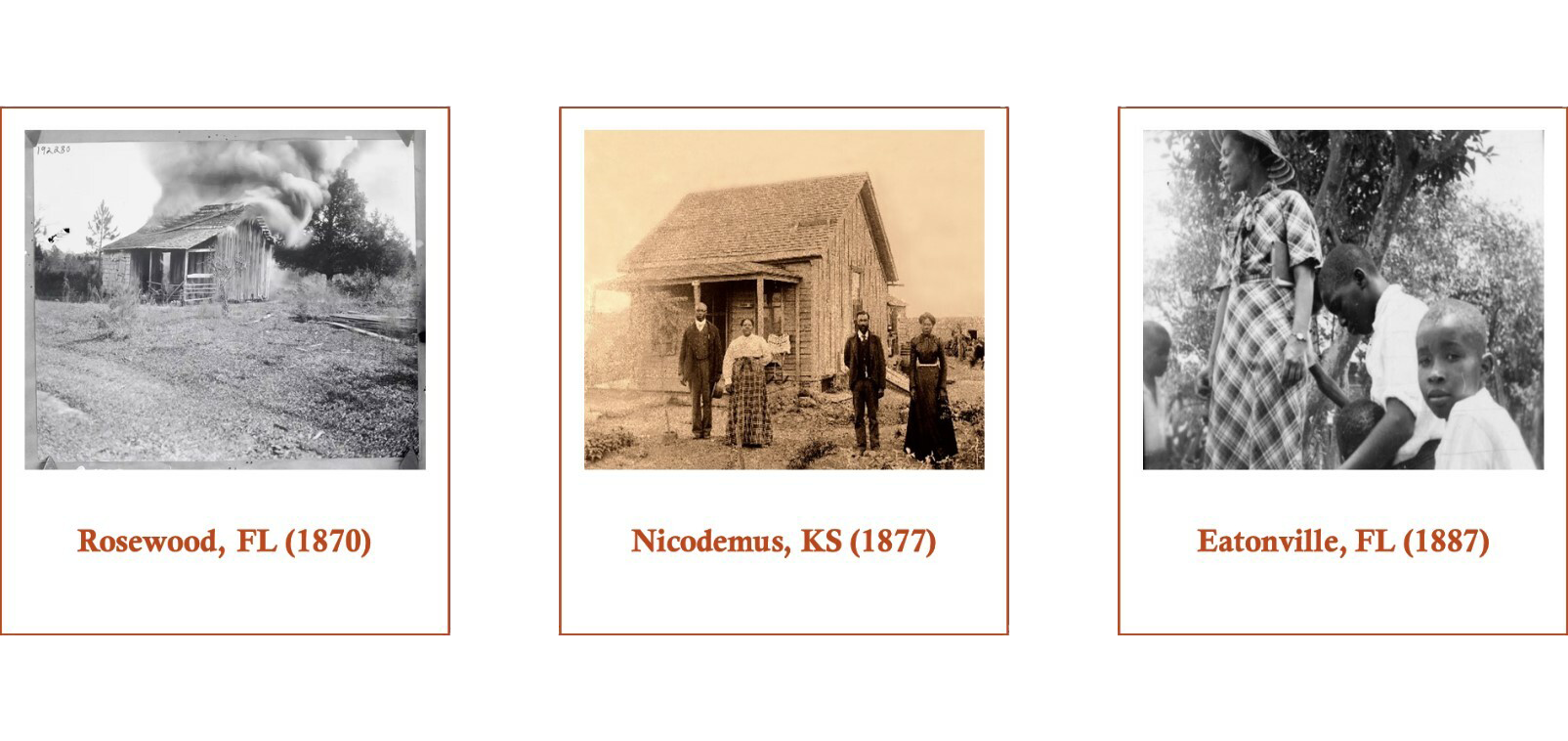

Archaeologists, cultural resource management professionals, architectural historians, and even government agencies are endeavoring to bring attention to the FCs around the country. I situate FC preservation among similar efforts to protect and interpret southern African American places and placemaking. Grassroots organizations like the Historic Black Towns and Settlements Association advocate for funding and support for incorporated Black towns (three of which are shown in Figure 2) including Tuskegee, Alabama, Mound Bayou, Mississippi, and Rosewood and Eatonville, Florida, and western All-Black Towns in Oklahoma and Kansas.6 Some of these towns still have substantial populations, are mapped, and often have politically sophisticated leaders. By contrast, FCs were often never officially incorporated, have small populations, and no official representation concerning land use issues decided in Texas on the city level. Historically, a Texas FC was “‘individually unified only by church and school and residents’ collective belief that a community existed.”7 A lack of documentation and compliance with sociolegal constructions of place, unfortunately, caused several FCs to disappear from public records, maps, and memory as their populations, historic buildings, and visibility declined after World War II. Further, a lack of estate planning made their landowners vulnerable to land loss. Sprawl, climate change, and gentrification have endangered what buildings remain.

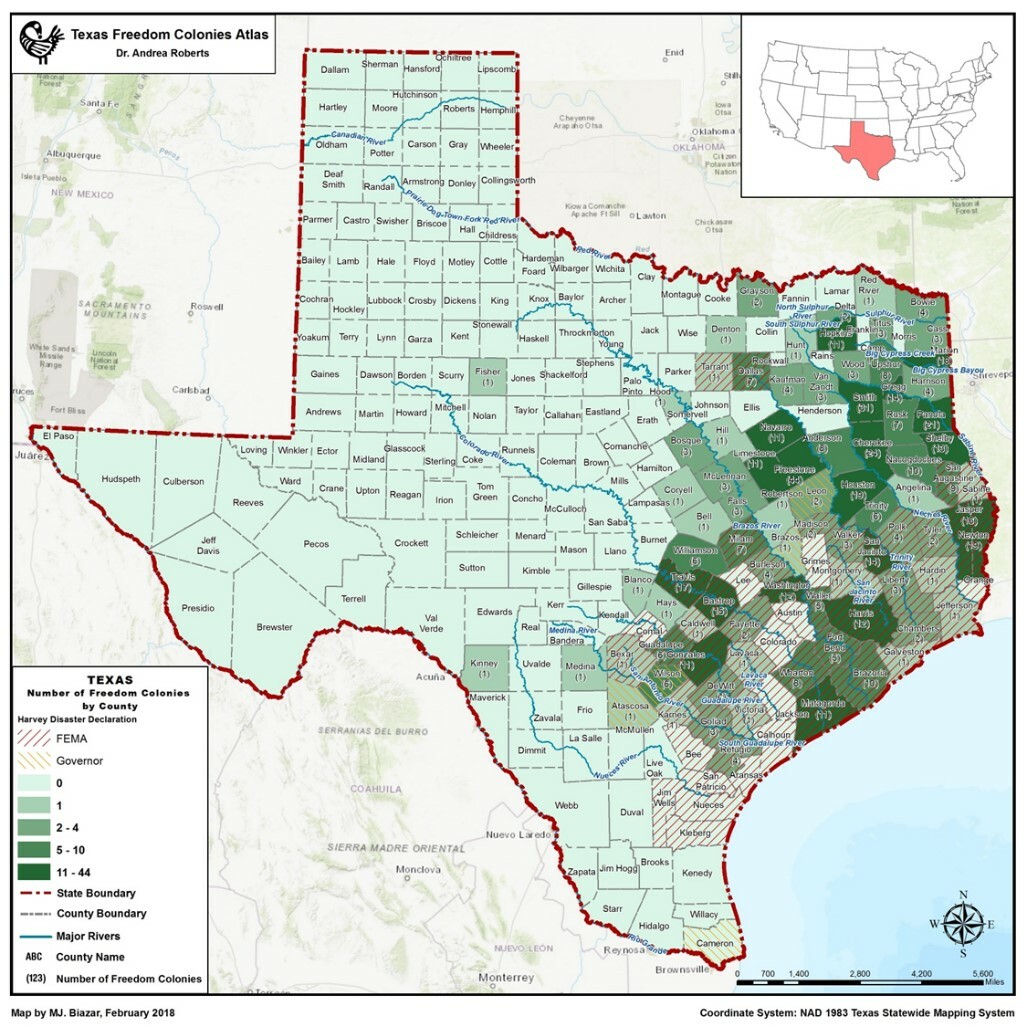

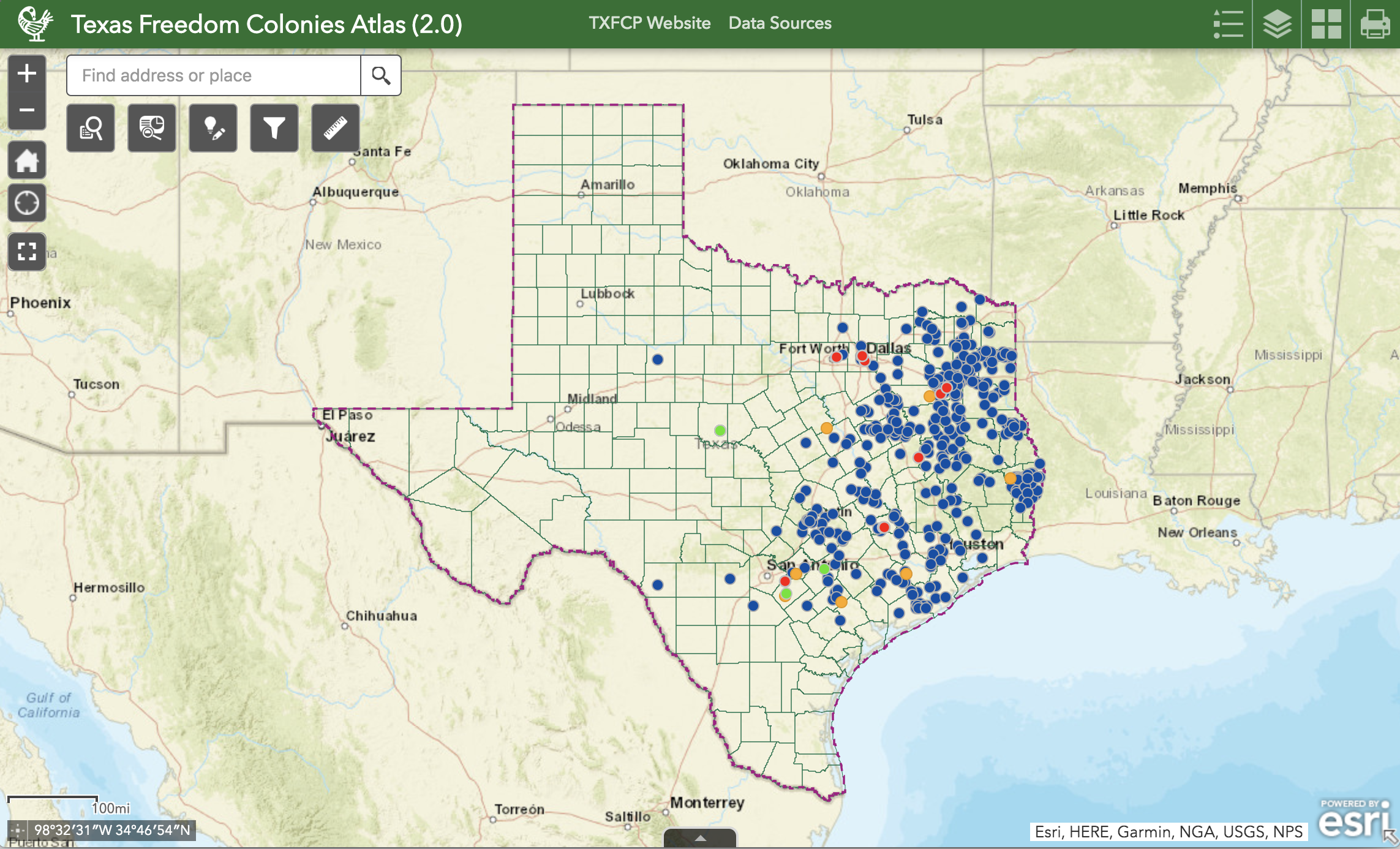

Furthermore, FCs were often founded in bottomland in low-lying areas.8 The legacy of these geographical vulnerabilities is highlighted by the FEMA - Hurricane Harvey Impact layer of the Texas Freedom Colony Atlas, (seen in figure 3) which shows that 229 FCs are in fifty-three FEMA designated counties, constituting 41% of total FCs or 64 % of the 357 mapped FCs. Further, the prevalence of unclear titles among landowners and lack of historical integrity of properties in FCs make them ineligible for FEMA, SBA, and HUD recovery funds 9 and even less likely to be considered endangered by public preservation agencies.

All of these environmental and political vulnerabilities compromise FC buildings and structures. As a result, while primary and secondary sources necessary to form a strong basis for historical argumentation may be available for FCs, that evidence is subordinate to historic preservation’s regulatory requirement of materiality or integrity. FC’s built environments, especially when geographically and historically situated in vulnerable areas lacking government investment, require different forms of evidence of place to enable interpretation, and recognition of their freedom-seeking heritage. This article argues that social and “sonic”10 histories offer evidence of historically significant Black landscapes, rendered ungeographic11 by historic preservation’s authorized heritage discourse and environmental vulnerability.

Significance and Integrity: National Historic Preservation Regulations

To understand how historic preservation determines what makes a place historic and thus worth recognizing or in some cases providing certain protections, I will focus on two aspects of the federal regulations: historical significance and integrity. These criteria are important to planners and policymakers because they determine why a building or place is worth preserving or designating “historic.” 12

The criteria are based on the “quality of significance in American history, architecture, archeology, engineering, and culture is present in districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects that possess integrity of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association.” More specifically, these properties must be sites, people, or architectural examples that are significant to history or prehistory. 13 The significance of historic sites or properties is determined using the National Register’s Criteria for Evaluation. Dimensions of significance are the architectural and historic value of the property, its age, whether a notable resident lived in the house, evidence of a distinct settlement pattern in a potential district, or architectural style. A site need only reflect one dimension of significance but could be deemed ineligible based on its lack of integrity. The integrity of a site refers to the degree to which it is physically intact and in a location or context relevant to the period of historic significance. The National Register criteria guide determinations of what qualifies for federal tax benefits.14 State level markers are available to properties in Texas that are at least 50 fifty years old, and are historically or architecturally significant, whereas subject markers can recognize individuals, events, communities, and institutions.15

While the criteria serve as a valuable guide, they require a high level of expertise (usually requiring applicants to hire architects or archaeologists) to survey and document to federal specifications. Specifically, the emphasis on the built environment and architecture has privileged the material over the intangible culture making it difficult for freedom colonies (FCs) to be listed. All designations, protections, and incentives are based on a regulatory framework that emphasizes strict adherence to regulations that facilitate erasure.

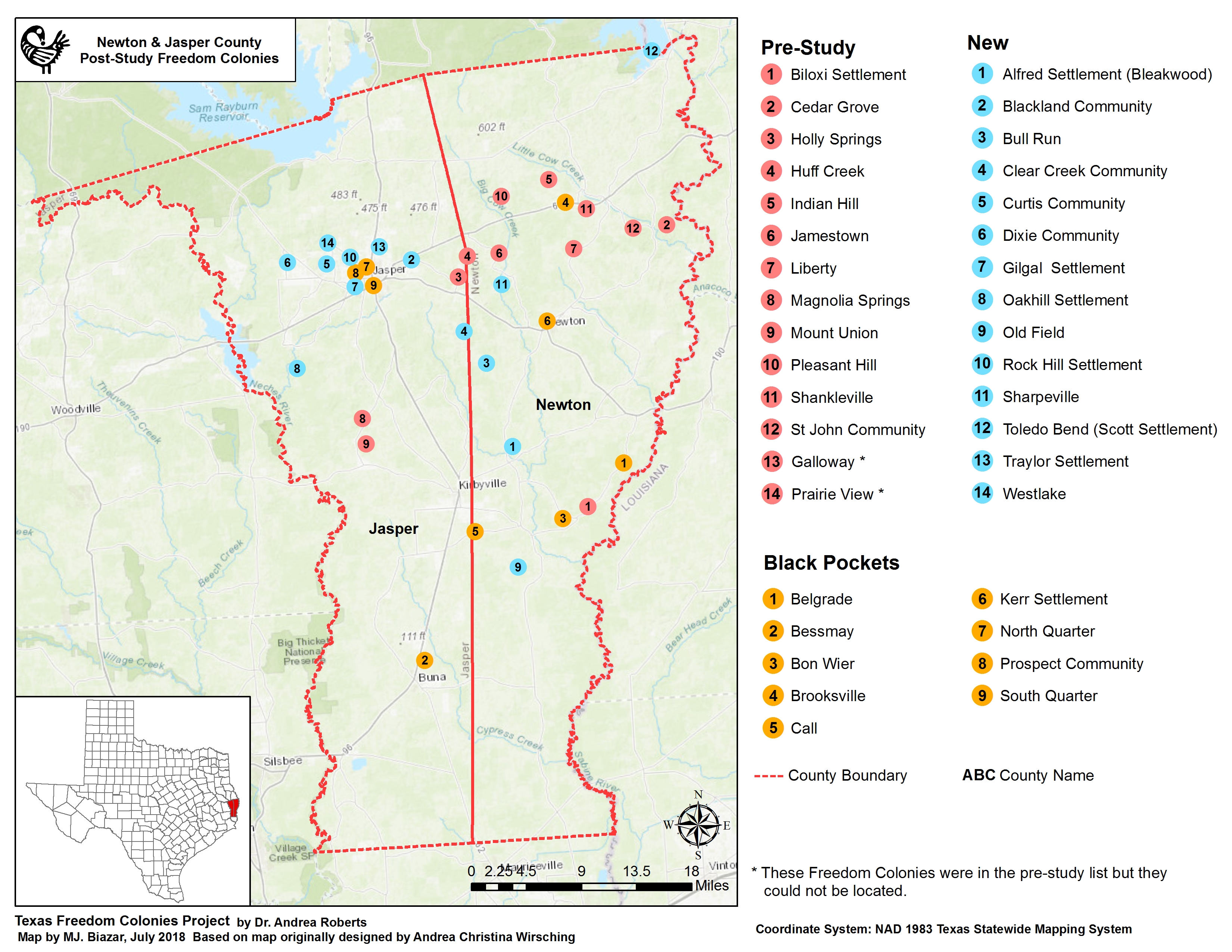

Un-authorized Heritage: Newton and Jasper County Freedom Colonies and Black Pockets

At the pre-study stage of my research in Deep East Texas, I identified only 14 freedom colony settlements. I have identified twenty-four more place names associated with FCs and their anchor sites in Newton and Jasper Counties. A map (shown in figure 4) generated after a two-year archival and ethnographic study revealed the existence of places unmapped or absent from lists of historic sites recognized by the state or federal government, indicating a disparity between the number of freedom colonies, which once existed, and the markers recognizing them. A 2015 review of Texas State Historical Markers on the state online atlas revealed sixty-one properties and sites recognized through the program. Of those places or sites listed, a majority are classified as graveyards or cemeteries (twenty-one), followed by churches or religious sites (ten), and cities and towns (seven). In Newton County, three of those “towns” are the Biloxi, Cedar Grove, and Shankleville FCs. The other markers recognize an African American church and one of the founders of Shankleville, Stephen McBride. Compared to Newton County, Jasper County has six state historical markers recognizing African American affiliated sites, none of which are FCs. Between the two counties, there are eleven sites on the National Register of Historic Places, but the Addie and AT Odom Homestead in Shankleville is the only African American site listed. The FCs clusters without markers were areas bifurcated by roads or abandoned after the once dominate corporate mills left Newton County.

Critiques of the Significance and Integrity Framework

Theorists contest the “expert” domination of preservation that informs the regulatory framework. Randall Mason maintains that the physical fabric and expertise have been overemphasized at the expense of the “memory/fabric connection,” a broad term that includes landscapes and material culture at all scales in the environment.16 The integrity of the built environment is not always what engenders support and action among descendants, but rather the cultural continuity reflected in the videos of homecoming celebrations. For many people, creating and preserving spaces where people can practice values associated with their culture and gather in their settlements is the priority.

An urban planning history and ethnographic study of freedom colony vulnerabilities and grassroots preservation gave birth to the Atlas. The map emerges from a study conducted 2014–2016 during which the author collected archival materials; audiovisual files of forty-eight interviews and homecoming events, cemetery tours, and meetings; field notes; and US Geological Survey Spatial Data (GSSD) of FCs located in Newton and Jasper Texas counties. The study heavily relied upon intangible heritage because for some FCs, the assemblage of “citizens” attending annual events is all the evidence that a place existed.

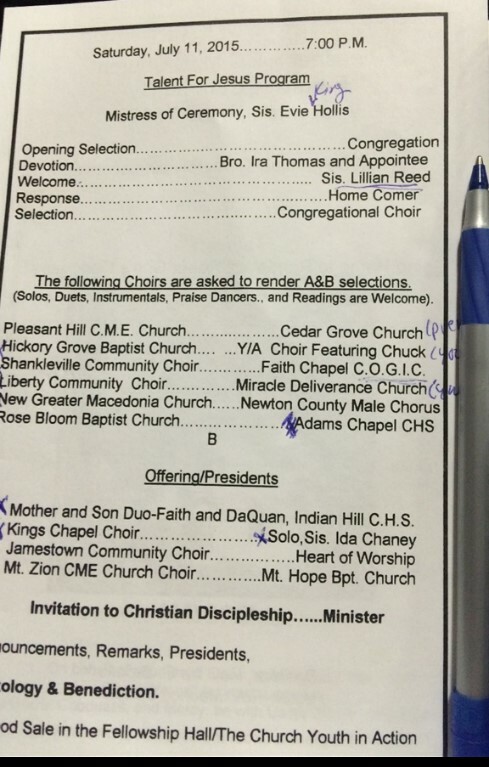

Observations of annual, commemorative gatherings such as family reunions and community homecomings indicated that these events helped sustain the diaspora’s attachments to FCs. These events are a historical artifact of the Great Migration, as they were founded to ensure those who left rural Texas for big cities would return home. Homecoming presidents from Jasper and Newton County freedom colonies (shown in figure 4) act as a cooperative network, which gather annually at each other’s two-day gatherings. The events celebrate not only the heritage of the community, but the offering of funds collected for the maintenance of each settlement’s cemetery. Artifacts of these events are sonic and ephemeral and include paper programs (such as the one pictured in figure 6), which provide social histories of FCs. Programs distributed to guests list visiting choirs and congregations from settlements whose names no longer appear on maps or anywhere else in the public record. Freedom colonies are often only recognized and remembered during the two-day events in which music and memories about settlements are shared among descendants, extended family, and church families. Witnessing and curating evidence of the social history makes visible the historically significant sites overlooked by preservationists due to regulatory standards, which downplay the importance of intangible heritage. Several properties and places located in the study area are historically significant and meaningful to descendants yet not designated historic or protected sites.

The research process solidifies the argument that embracing creative and performative assemblage, orality, and memory was required to map the balance of the unknown FCs. This initial mapping exercise gave birth to the statewide mapping project. The current digital humanities platforms holding data—a Blogger.com website and ArcGIS Survey—enable educators, researchers, and descendant communities to demonstrate across disciplines and outside academia, the historical significance of FC, and facilitate re-envisioning citizen participation, mapping, and preservation planning.17 In addition to the map (shown in figure 7), the website in which it is embedded collects resident memories and photos. At the time of this article’s publication, 357 of 557 FCs have been mapped, with 322 FC located using publicly available data.

Historic preservation standards around what defines place and historical significance obscure the disappearing heritage of FCs, particularly in those settlements with low populations and little remaining built environment. Preservation policy, as a result, has a disparate impact on the survival of many FCs that might otherwise thrive and benefit from federal protections and tax breaks if the property-based bias was eliminated. Recording commemorative events at buildings and spaces with compromised integrity but embodied and performed constructions of a community might substantiate significance. However, the evidence, embedded in memory and orality, are distributed broadly across various archives, commemorative practices, and declining structures. The goal of the Atlas and its accompanying survey of descendants is to aggregate layers of authorized evidence and crowdsourced data to empower residents and to visualize the hidden histories, social vulnerabilities, and current grassroots preservation activities for historians, policymakers, and preservationists.

Bibliography

Boyd, Candice, and Michelle Duffy. “Sonic Geographies of Shifting Bodies.” Interference: A Journal of Audio Culture 1, no. 2 (2012): 1–7.

Catalani, Anna, and Tobias Ackroyd. “Hearing Heritage: Soundscapes and the Inheritance of Slavery.” Gothenburg, Sweden, 2012.

Kelly, Joan. Women, History & Theory: The Essays of Joan Kelly. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

Kuris, Gabriel. “A Huge Problem in Plain Sight: Untangling Heirs; Property Rights in the American South, 2001–2017.” January 24, 2018. https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/publications/huge-problem-plain-sight-untangling-heirs-property-rights-american-south.

Mason, Randall. “Fixing Historic Preservation: A Constructive Critique of ‘Significance’ [Research and Debate].” Places 16, no. 1 (2004). http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/74q0j4j2.

McKittrick, Katherine. Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

National Park Service. “Section II: How to Apply the National Register Criteria for Evaluation, National Register of Historic Places Bulletin (NRB 15).” Accessed August 27, 2014. http://www.nps.gov/nr/publications/bulletins/nrb15/nrb15_2.htm.

Roberts, Andrea. “The Texas Freedom Colonies Project Atlas & Study.” Oaktrust Repository. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University, 2018.

Roberts, Andrea R. “Performance as Place Preservation: The Role of Storytelling in the Formation of Shankleville Community’s Black Counterpublics.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage, 2018, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/20518196.2018.1480002.

Sandercock, Leonie. “Framing Insurgent Historiographies for Planning.” In Making the Invisible Visible: A Multicultural Planning History, edited by Leonie Sandercock. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Sanders, Brandee, and Monee Fields-White. “History’s Lost Black Towns.” The Root. January 1, 2011. https://www.theroot.com/historys-lost-black-towns-1790868004.

Schweninger, Loren. Black Property Owners in the South, 1790–1915. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Sitton, Thad, and James H. Conrad, Freedom Colonies: Independent Black Texans in the Time of Jim Crow. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2005.

Smith, Laurajane. “Editorial.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 18, no. 6 (November 2012): 533–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2012.720794.

Smith, Susan J. “Soundscape.” Area 26, no. 3 (1994): 232–240.

State of Texas Legislature. “Government Code Chapter 442. Texas Historical Commission.” Government. Texas Constitution and Statutes. Accessed February 15, 2016. http://www.statutes.legis.state.tx.us/Docs/GV/htm/GV.442.htm.

Temple-Raston, Dina. A Death in Texas: A Story of Race, Murder, and a Small Town’s Struggle for Redemption. New York: H. Holt, 2002.

Notes

-

Kelly, Women, History & Theory; Sandercock, “Framing Insurgent Historiographies.” ↩

-

Smith, “Editorial.” ↩

-

The Lower Southern states included in Schweninger’s comparison are Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas. ↩

-

Schweninger, Black Property Owners, 164. ↩

-

Temple-Raston, A Death in Texas. Huff Creek settlement was the site of the 1998 dragging death of James Byrd. ↩

-

Sanders and Fields-White, “History’s Lost Black Towns.” ↩

-

Sitton and Conrad, Freedom Colonies, 18. ↩

-

Roberts, “Performance as Place Preservation.” ↩

-

Kuris, “A Huge Problem in Plain Sight.” ↩

-

Boyd and Duffy, “Sonic Geographies of Shifting Bodies”; Smith, “Soundscape”; Catalani and Ackroyd, “Hearing Heritage.” ↩

-

McKittrick, Demonic Grounds. ↩

-

Mason, “Fixing Historic Preservation,” 64. ↩

-

National Park Service, “Section II.” ↩

-

“Protection” means a local review process under State or local law for proposed demolition of, changes to, or other action that may affect historic properties designated” NHPA of 1966. ↩

-

State of Texas Legislature, “Government Code Chapter 442.” ↩

-

Mason, “Fixing Historic Preservation,” 71. ↩

-

Roberts, “The Texas Freedom Colonies Project Atlas & Study.” ↩

Authors

Andrea Roberts,

Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning, Texas A&M University, aroberts318@tamu.edu,