Women and Federal Officeholding in the Late Nineteenth-Century U.S.

Abstract

The last decades of the nineteenth century witnessed a surge of women into the public sphere. Through leadership positions in voluntary associations, religious groups, and other social reform movements, women shaped public policies on issues like education, welfare, sanitation, temperance, and (most famously) women’s suffrage.1

They also entered public life through official government positions. During and after the U.S. Civil War the federal government established a host of new agencies and initiatives that both expanded its administrative capacity and swelled the ranks of its workforce. The pioneering work of historian Cindy Aron has documented how thousands of largely middle-class women secured some of these new positions, working as clerks, copyists, and other positions for federal agencies in Washington, D.C.2

Outside of the nation’s capital, however, the picture is much murkier. When and how did women enter the public sector workforce across the rest of the country? The answer lies with the federal government’s single largest organization: the Post Office Department.

As is often the case for women’s history, the archival record is frustratingly limited and incomplete. No single source systematically records the number of women who served in the Post Office Department – much less the wider federal government – on a year-by-year basis. Instead, I turn to three different measurements to try and distill a larger pattern. On their own, each method is incomplete. Taken together, however, they point to the same trend: beginning in the 1860s and accelerating through the 1870s and 1880s, women served as postmasters in the federal government in ever-increasing numbers. By 1891, roughly ten percent of the nation’s post offices (6,335 in total) were run by women.3 This wave of female officeholders was a crucial wedge for women’s broader entry into public life during the late nineteenth century.

Measurement #1: Presidential Appointments

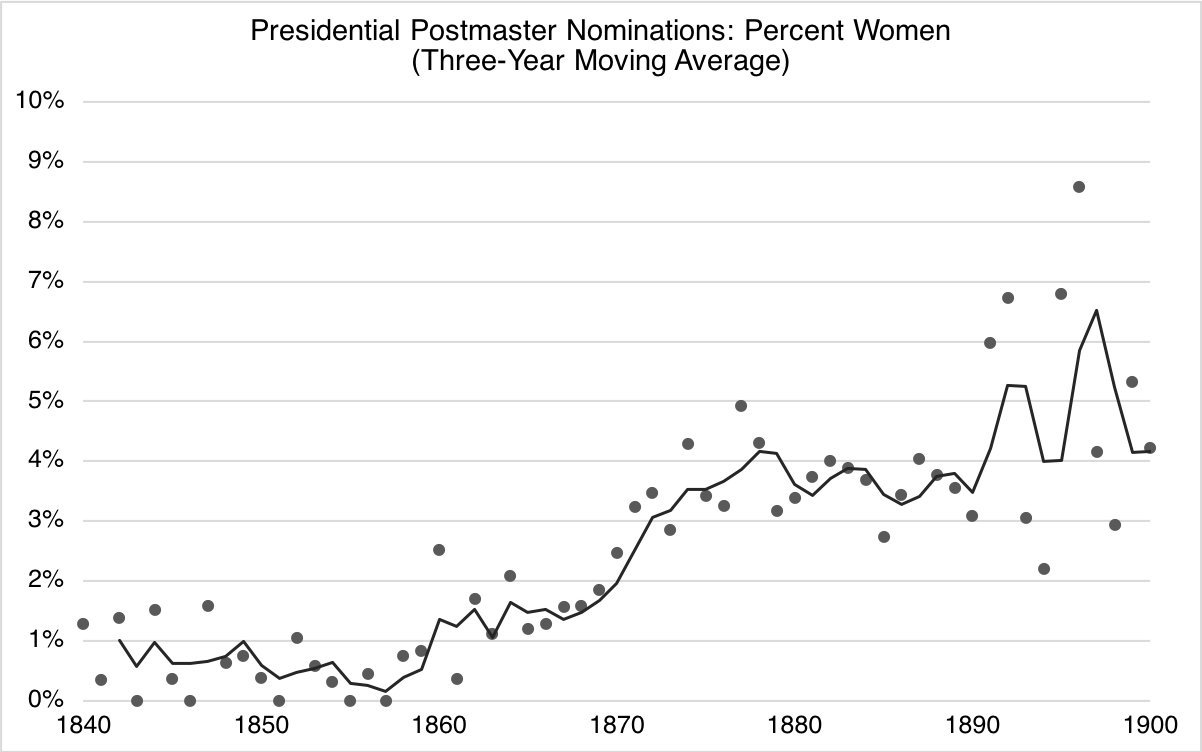

The first measurement comes from a dataset collected by political scientist Scott James. It contains information about some 49,000 people appointed by the president and sent to the U.S. Senate for confirmation between the years 1829 and 1917. The dataset covers many different federal agencies, but the bulk of these nominations were for so-called “Presidential” postmasters who managed the nation’s large urban post offices. Using the gender package in the programming language R, I inferred the gender of these Senate-confirmed appointees based on their first names. Through 1865, the number of women appointed to these Presidential postmaster positions never exceeded five women in a single year. By 1895, roughly fifty-five women were appointed. This growth cannot be chalked up to a wider expansion in the federal workforce. Even when calculated as a percentage of all Presidential postmaster appointments, the share of women roughly tripled between the 1860s and the 1890s (see figure 1).4

A few notes of caution: these numbers are estimated inferences. They rely on a computational method that assumes a problematic gendered binary of naming practices and says absolutely nothing about how individuals may have identified themselves. Moreover, the gender package was not able to infer the gender for every name in the dataset. In cases of uncommon first names (“Selucius Garfield”) or initials (“A.P.K. Safford”), it left the gender unidentified. It is safe to say, then, that these figures undercount the proportion of women in the dataset. Finally, these Senate-confirmed appointments were only a tiny fraction of the nation’s total postal workforce. To see if this trend can be verified, we need to turn to other sources.5

Measurement #2: State-Level Data

The vast majority—around 95–96%—of postmaster appointments did not require Senate confirmation.6 For these offices, the position of postmaster was rarely a full-time occupation. Instead, a local private business person (usually a storeowner) would run the post office out of their storefront or other place of business. For most, the work was part-time and the pay was modest.

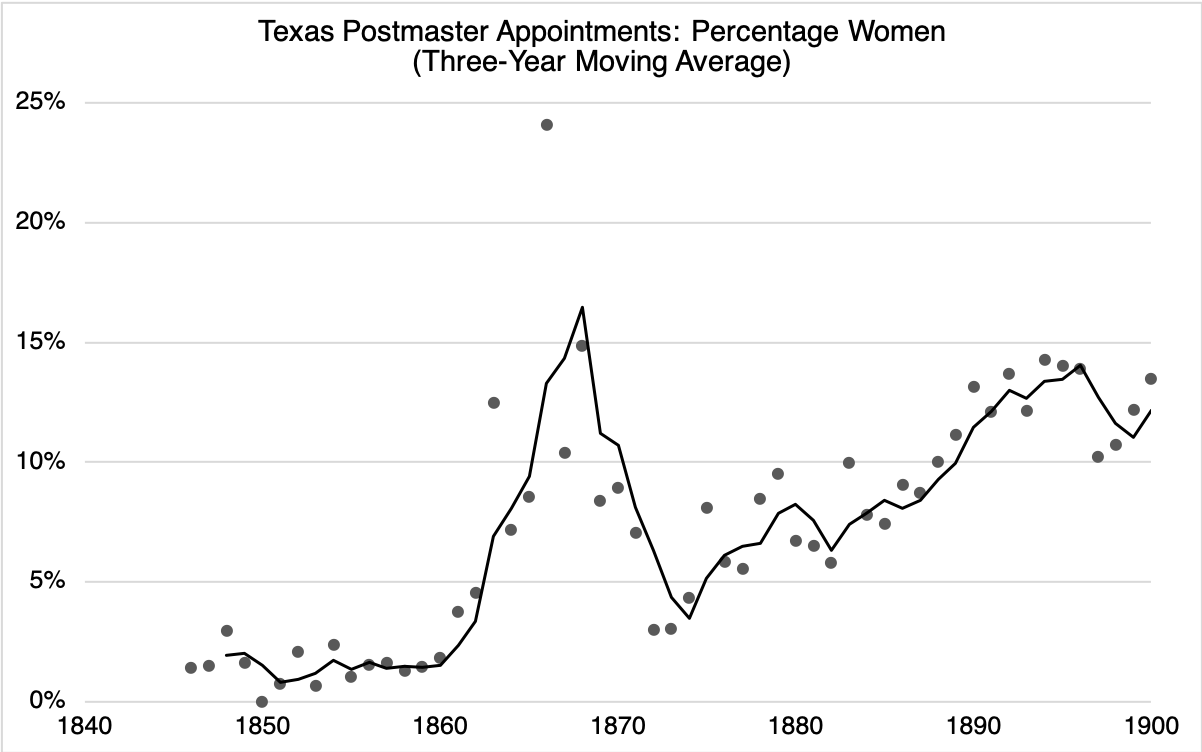

Records for these smaller offices are harder to track. Fortunately, postal history attracts a number of philatelists and amateur enthusiasts. In the mid-2000s, a postal historian named Jim Wheat posted webpages containing transcriptions of every postmaster appointed in the state of Texas between 1846–1930. I scraped this data from his website, processed it into a database, and then used the same gender R package to infer the gender of some 38,500 Texas postmasters. Jim Wheat’s dataset of Texas postmasters shows a similar pattern as Scott James’s dataset of Presidential postmaster appointments, with a steady rise in the share of female appointees over the final decades of the nineteenth century (see figure 2).7

There are some telling differences between the two measurements. First, as shown in the chart in figure 2, the share of women in Texas post offices spiked during the 1860s and early 1870s. This was due to Texas joining the Confederate Rebellion, throwing the state’s postal system into temporary flux. When the so-called “ironclad” oath effectively barred ex-Confederate soldiers from taking public office after the war, Texas women temporarily stepped into the vacuum.8 When loyalty restrictions eased following Reconstruction, the share of women dropped back down before climbing steadily over the next two decades.

The second difference between the two datasets was that women generally made up a larger share of Texas postmaster appointments (10–15% by the 1890s) than they did Presidential postmaster appointments (3–7% by the 1890s). This was due to the fact that there was more competition for the higher-paying Presidential postmaster positions in Scott James’s dataset compared to lower-paying positions that make up the bulk of Jim Wheat’s dataset.

Measurement #3: N-Grams

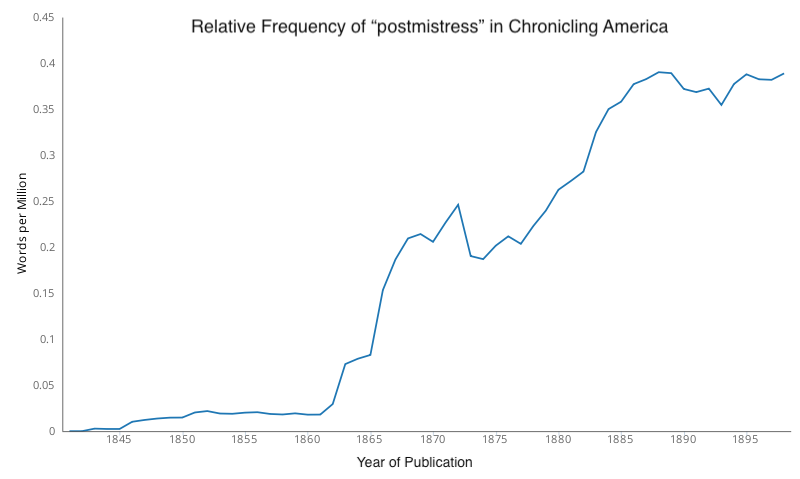

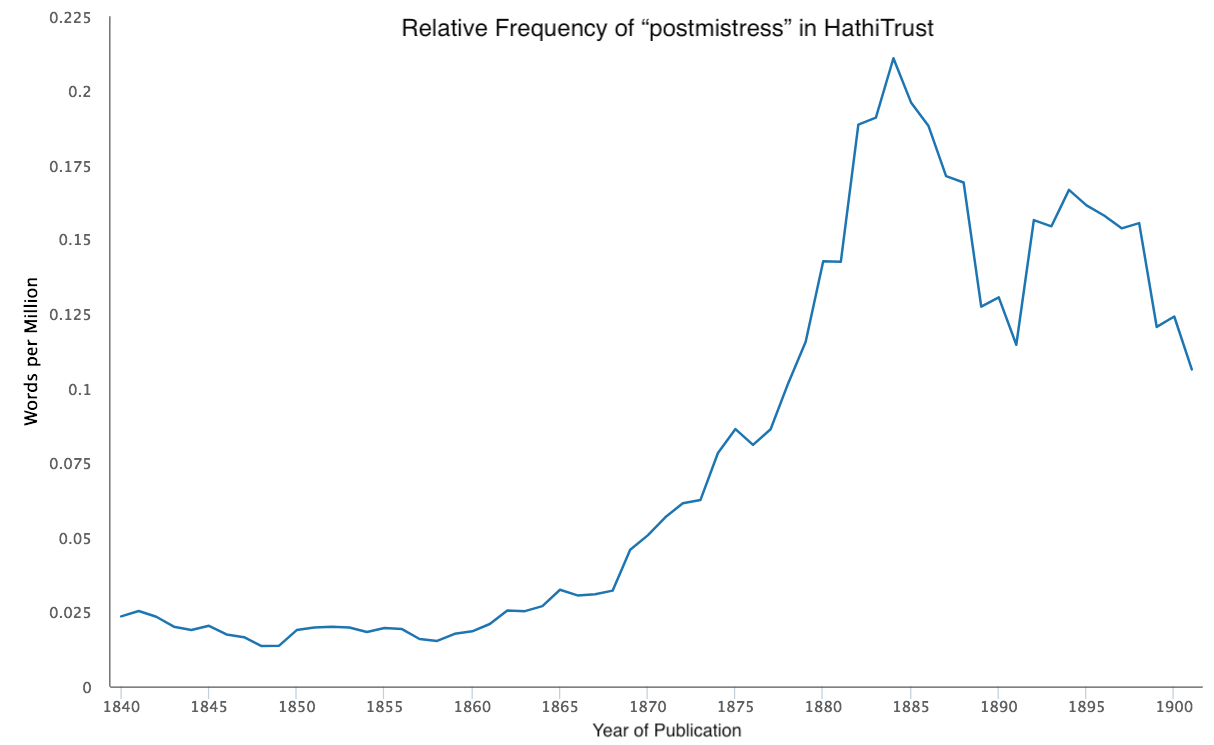

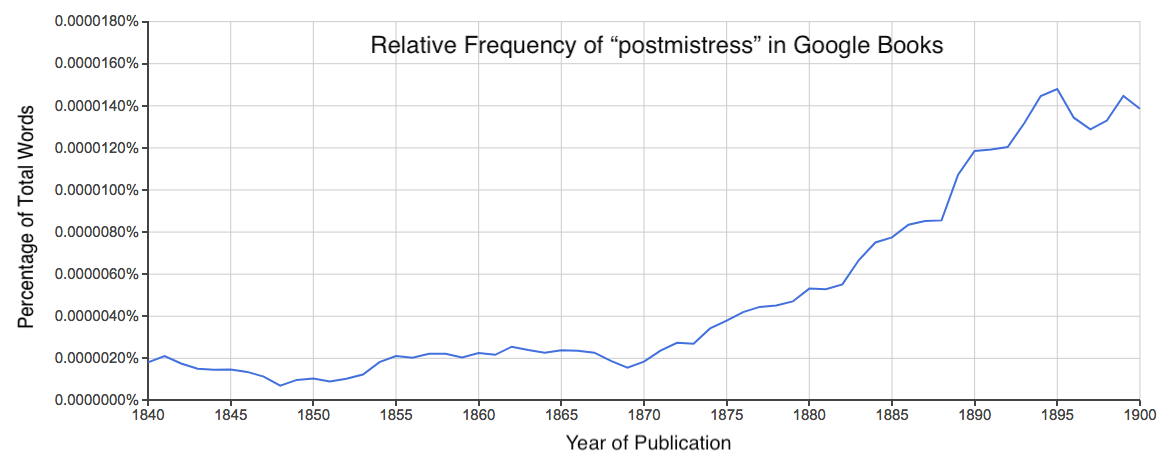

The third measurement for tracking the entry of women in the postal workforce comes from three large-scale textual databases: the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America collection of historical newspapers along with the digital libraries HathiTrust and Google Books. None of these databases measure the number of female postmasters directly. Instead, I used n-grams (the relative frequency of strings of words within a corpus) as a proxy indicator by tracking the phrase “postmistress” (postmasters who were women) across the three historical databases. All three datasets show the same pattern, and one that mirrors that of the first two datasets: use of the phrase “postmistress” rose dramatically in printed texts during the 1870s and 1880s. (See figures 3, 4, and 5.)

On their own, the charts in figures 3, 4, and 5 don’t tell us all that much. Compared to the first two datasets, they are a far-removed proxy measurement for a real-world pattern. The relationship between lexical use and material changes is fuzzy at best: “postmistress” might have become a more popular phrase for reasons other than (or in addition to) the entry of women into the postal workforce. Moreover, all three databases have their own pitfalls, from corpus coverage to OCR quality.9

Given that this lexical pattern roughly mirrors the trajectory of postmaster appointments in the first two datasets, however, we can hypothesize that there was at least some connection between them. Moreover, n-gram measurements give us a slightly different vantage point. Whether or not they measure an actual rise in postmistresses, they do indicate that nineteenth-century people were commenting on the phenomenon of women postmasters more frequently.

The Big Picture

Like the parable of the blind men and the elephant, none of the above datasets tell the entire story. Their creators—a political scientist, an amateur historian, the Library of Congress, HathiTrust, and Google—did not make them in order to track the entry of women into the federal workforce. They had to be repurposed and reprocessed to answer this question. In an age of ever-expanding digitized historical material, stitching together these kinds of seemingly disparate datasets to look for shared patterns is becoming more and more common. It needs to be done, however, with a concrete understanding of what is and is not included in these measurements. And even when a trend does emerge, historians still need to interpret its causes and significance.

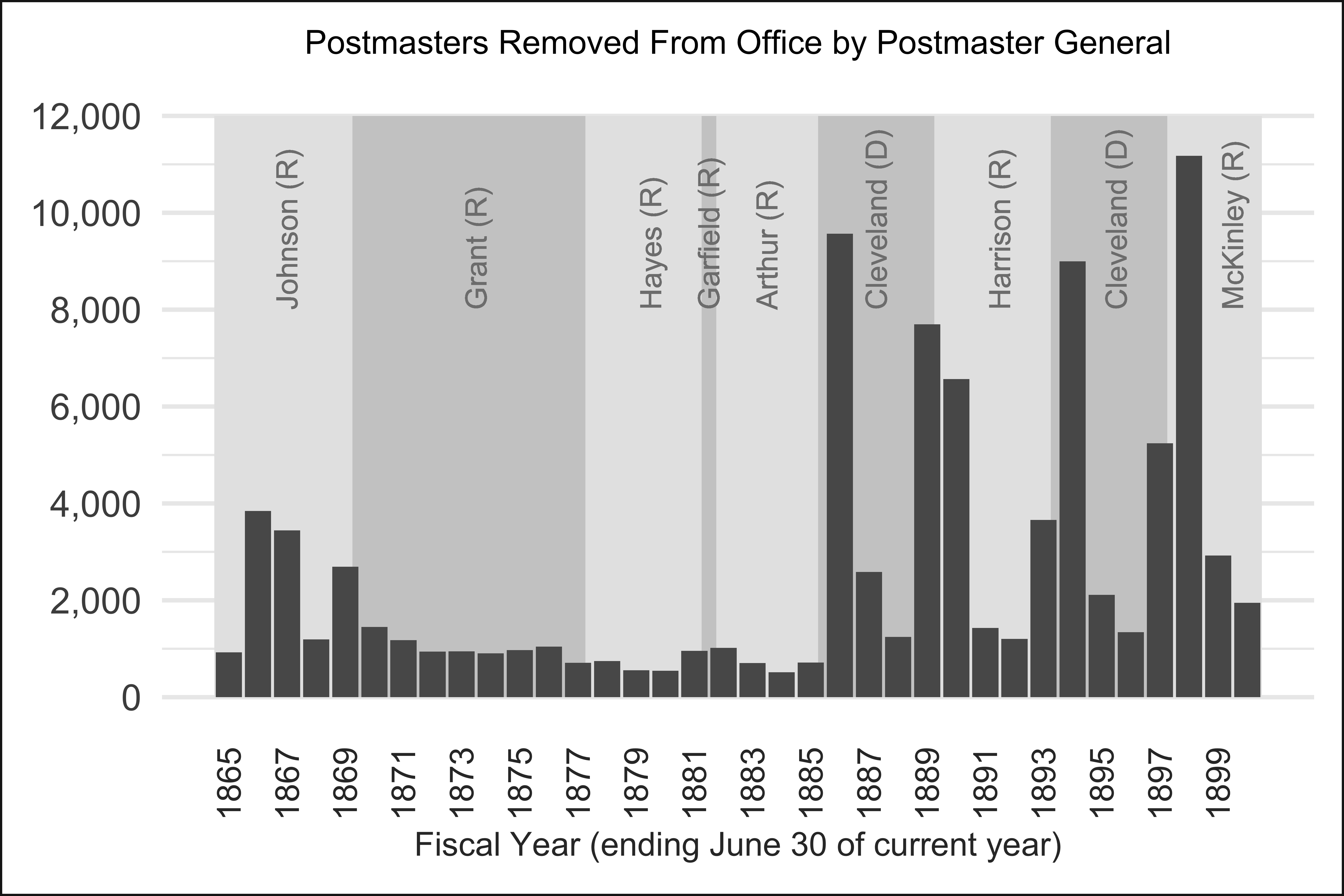

What, then, explains the widespread rise of women as postmasters and why does it matter? The position of postmaster presented a number of advantages to women hoping to secure a position in government. One advantage was that the position of postmaster was the most commonly available federal job. Outside of times of war, the Post Office Department regularly employed more people than the entire rest of the executive, judicial, and legislative branches combined.10 Moreover, because postmasters were typically linked to party patronage and electoral politics, turnover in office was common. Whichever party controlled the presidency had the power to dismiss and appoint most of the nation’s postal workforce. This meant that every changeover in the executive branch brought a wave of removals and resignations in the nation’s post offices. (See figure 6.) Although the carousel of partisan patronage wasn’t good for job security, it did give women many more opportunities to jump on board.

The second advantage had to do with the job itself. Unlike today, most post offices were an extension of the postmaster’s private business or residence. Many of them consisted of little more than the cluttered corner of a general store. This meant that postmasters themselves were seen as a hybrid of private citizens and public officeholders. This blurring between private and public gave women an opening in which to step into public office without representing a wholesale transgression of traditional gendered boundaries. This was especially true if the post office itself was housed within the postmaster’s home, a space over which women held traditional authority.11 The nature of the work helped as well. Postmasters did not wield regulatory or coercive power. They were not tax collectors or constables, instead acting as vendors who provided a popular public service. This made local communities generally more comfortable with a woman holding the position—even as writers lampooned postmistresses as gossiping busybodies and newspapers never tired of making endless puns about their ability to handle both “the mails” and “the males.”12

The entry of women into these offices represented a quiet yet important initial foray into public officeholding for women who were eager to take on official roles in government and politics. The position may have paid poorly, but it did come with benefits. It carried a certain degree of prestige: small-town postmasters were often seen as “local notables” on par with a sheriff or justice of the peace. Post offices were also clearinghouses of information where people would regularly congregate to exchange news and gossip. Postmasters knew what magazines or newspapers their neighbors subscribed to, which parties and organizations they belonged to, and who they were communicating with. Finally, given the partisan nature of the position, securing an appointment required the officeholder to lobby local and national politicians. This gave women a chance to establish channels of communication and develop important relationships that they could then turn towards other sorts of public pursuits.13

Finally, the sheer ubiquity of postmasters—numerically and geographically—meant that the position was one of the most common ways in which Americans first caught a glimpse of a woman serving in federal office. This early wave of public officeholding helped normalize the idea of women holding official government positions. Although a small-town postmaster was an unelected position with limited responsibilities, it nevertheless paved the way for women to take on larger roles in federal government. In 1920, for instance, Oklahoma voters elected Alice Mary Robertson to the U.S. House of Representatives just a few months after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, making her the second woman to serve in U.S. Congress. It was not, however, Robertson’s first time to hold federal office. A decade before, she had run the post office in Muskogee as an official U.S. postmaster. She was far from alone.14

Bibliography

Aron, Cindy. Ladies and Gentlemen of the Civil Service: Middle-Class Workers in Victorian America. Oxford University Press, 1987.

Blevins, Cameron. Gossamer Network: The U.S. Post and State Power in the American West. New York: Oxford University Press, forthcoming.

Boggs, Mae Helene Bacon. My Playhouse Was a Concord Coach: An Anthology of Newspaper Clippings and Documents Relating to Those Who Made California History During the Years 1822–1888. Oakland, CA: Howell-North Press, 1942.

Cushing, Marshall Henry. The Story of Our Post Office. Boston, Mass: A. M. Thayer & Co., 1893.

Edwards, Rebecca. Angels in the Machinery: Gender in American Party Politics from the Civil War to the Progressive Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Foss, Sam Walter. “The Postmistress of Pokumville.” In Dreams in Homespun, 180–82. Boston: Lee & Shepard, 1898. http://books.google.com/books?id=YiQ-AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA180.

Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896–1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Greenwald, Maurine Weiner. “Working-Class Feminism and the Family Wage Ideal: The Seattle Debate on Married Women’s Right to Work, 1914–1920.” The Journal of American History 76, no. 1 (1989): 118–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/1908346.

James, Scott C. “Patronage Regimes and American Party Development from ‘The Age of Jackson’ to the Progressive Era.” British Journal of Political Science 36, no. 1 (2006): 39–60. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123406000032.

Library of Congress. “Alice Robertson, 1922.” Photographic Print, National Photo Company Collection. No. 17381 (January 3, 1922). https://lccn.loc.gov/2002697188.

“Males and Mails.” The United States Mail 3, no. 33 (June 1887): 122.

Mullen, Lincoln, Cameron Blevins, and Ben Schmidt. Gender: Predict Gender from Names Using Historical Data (version 0.5.2), 2018. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gender.

Painter, Nell Irvin. Standing at Armageddon: A Grassroots History of the Progressive Era. W. W. Norton & Company, 1987.

Pechenick, Eitan Adam, Christopher M. Danforth, and Peter Sheridan Dodds. “Characterizing the Google Books Corpus: Strong Limits to Inferences of Socio-Cultural and Linguistic Evolution.” PLOS ONE 10, no. 10 (October 7, 2015): e0137041. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0137041.

Richter, William L. “‘We Must Rubb Out and Begin Anew’: The Army and the Republican Party in Texas Reconstruction, 1867–1870.” Civil War History 19, no. 4 (1973): 334–52. https://doi.org/10.1353/cwh.1973.0041.

Rubin, Anne Sarah. A Shattered Nation: The Rise and Fall of the Confederacy, 1861–1868. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

United States. Annual Reports of the Postmaster General. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1865–1900.

United States Congress. Official Register of the United States. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1865–1899.

United States Congress. “Robertson, Alice Mary.” In Biographical Directory of the United States Congress: 1774-present. Accessed October 15, 2018. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=R000318.

Wallis, John Joseph. “Table Ea894-903 – Federal Government Employees, by Government Branch and Location Relative to the Capital: 1816–1992.” In Historical Statistics of the United States, Earliest Times to the Present, edited by Susan B. Carter, Scott Sigmund Gartner, Michael R. Haines, Alan L. Olmstead, Richard Sutch, and Gavin Wright. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Wheat, Jim. “Postmasters & Post Offices of Texas, 1846–1930.” December 28, 2006. Accessed January 10, 2013. http://sites.rootsweb.com/~txpost/postmasters.html.

Notes

-

Painter, Standing at Armageddon, 62–64, 231–35; Edwards, Angels in the Machinery, 12–58; Gilmore, Gender and Jim Crow, 31–60. ↩

-

Aron, Ladies and Gentlemen of the Civil Service. ↩

-

Cushing, Story of Our Post Office, 442–43; “1891 Annual Report of the Postmaster General,” 265. ↩

-

Many thanks to Scott James for providing his dataset: James, “Patronage Regimes and American Party Development from ‘The Age of Jackson’ to the Progressive Era.” Gender was inferred using: Mullen, Blevins, and Schmidt, Gender. ↩

-

The gender package was able to infer the gender of 41,520 appointees between 1840–1900, or 97.5% of all names for this period. ↩

-

In 1871, 96% of the post offices were fourth-class offices. “1871 Annual Report of the Postmaster General,” 85. In 1899, 94.4% of post offices were fourth-class offices. “1899 Annual Report of the Postmaster General,” 822–823. ↩

-

Varun Vijay helped process this data while working as an undergraduate Research Assistant at the Stanford Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis during the spring of 2015. Wheat, “Postmasters & Post Offices of Texas, 1846–1930.” I conducted a similar state-level analysis of Oregon during this same period, using bi-annual data from The Official Register of the United States that lists the names of every federal employee. This analysis showed a similar pattern: the proportion of postmasters who were women increased roughly fivefold from the 1870s to the 1890s. ↩

-

Richter, “We Must Rubb Out and Begin Anew,” 348–50. For the larger context of “loyalty oaths” in the South, see Rubin, A Shattered Nation, 164–71. ↩

-

Pechenick, Danforth, and Dodds, “Characterizing the Google Books Corpus.” ↩

-

Wallis, “Table Ea894-903.” ↩

-

The blurring of different kinds of work space and the opportunities this has provided for women can be seen especially clearly during times of war. See, for instance, Edwards, Angels in the Machinery, 12–38; Greenwald, “Working-Class Feminism and the Family Wage Ideal.” ↩

-

Foss, “The Postmistress of Pokumville.” For “mails/males” jokes, see Trinity Journal (Yreka, CA), March 22, 1873, quoted in Boggs, My Playhouse Was a Concord Coach, 584; “Males and Mails.” ↩

-

I explore the nineteenth-century U.S. Post in more detail in my forthcoming book, Blevins, Gossamer Network. ↩

-

United States Congress, “Robertson, Alice Mary.” ↩

Author

Cameron Blevins,

Department of History, Northeastern University, c.blevins@northeastern.edu,