“For the Love of People”

Berkeley's Rainbow Sign and the Secret History of the Black Arts Movement

Abstract

1. Hidden Figures: Mary Ann Pollar and the Black Female Leadership of Rainbow Sign

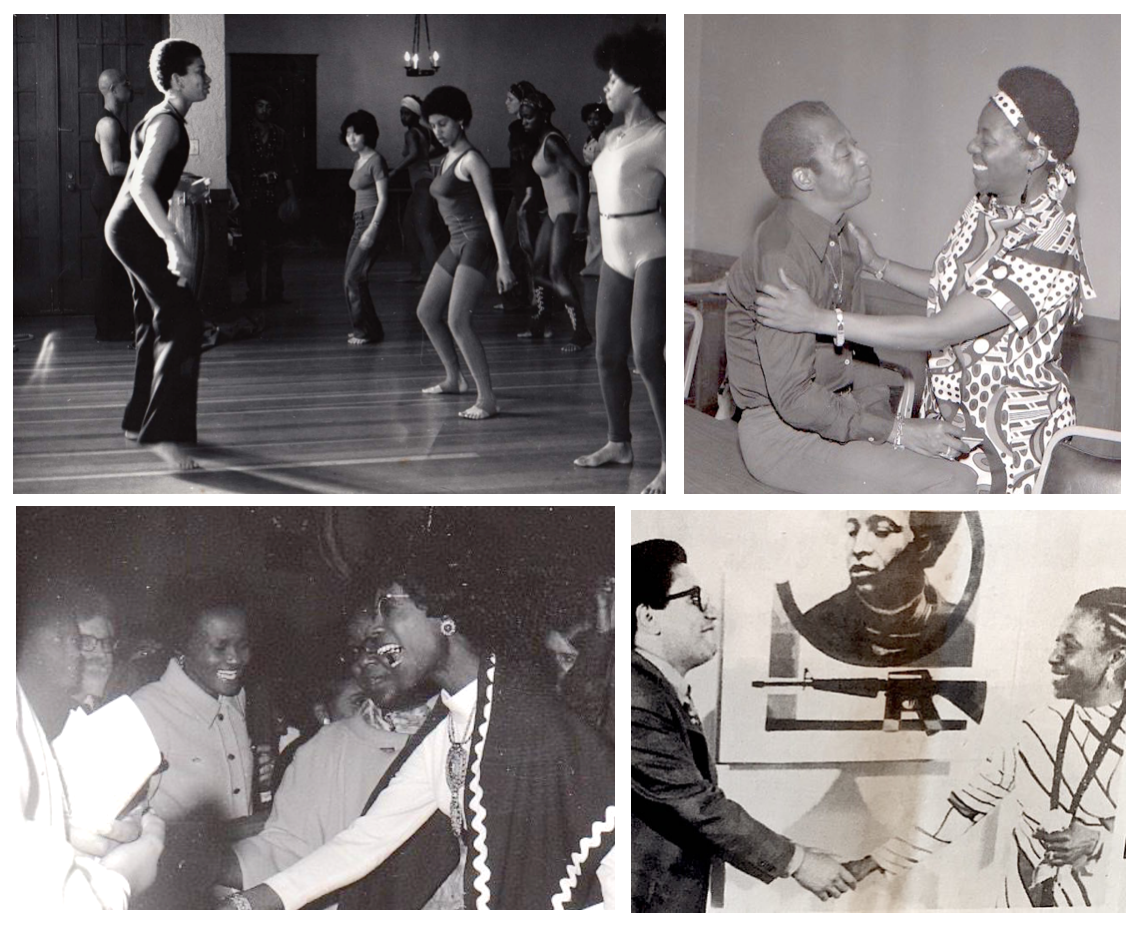

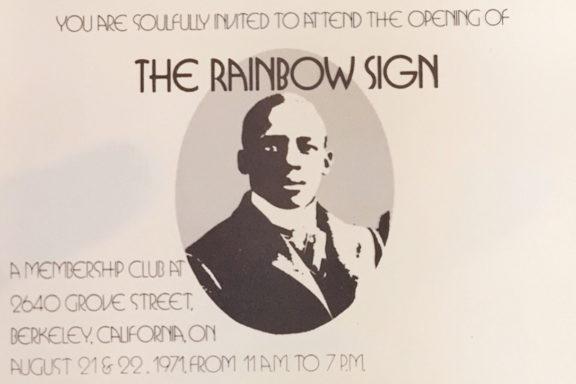

On the weekend of August 21, 1971, on a street that long had served as a dividing line between white and black Berkeley, a formerly dilapidated mortuary was reborn as Rainbow Sign, a black cultural center that, tellingly perhaps, has largely disappeared from histories of the Black Arts Movement.1

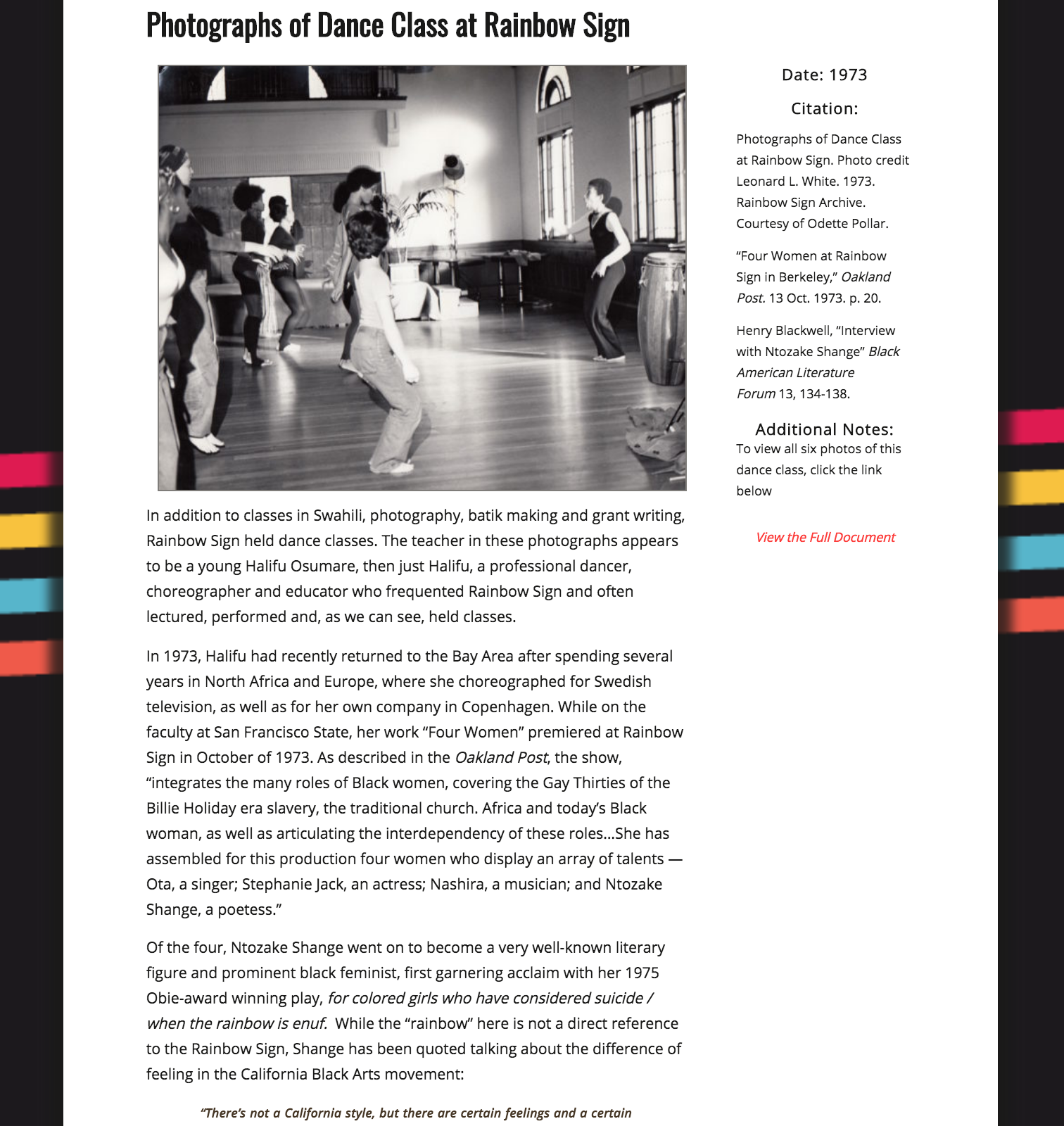

Brainstormed into existence by music promoter Mary Ann Pollar, with help from a group of black female professionals, Rainbow Sign sought simultaneously to “showcase the best there is of the Black experience” and to “set a Black table at which everyone is welcome to eat.”2 As art gallery, performance venue, lecture hall, rentable community meeting space, soul food restaurant and private membership club, Rainbow Sign projected a broad ethic of intercultural care—one which made the richness of black culture available for all committed to the struggle without compromising the centrality of the black community and its needs.

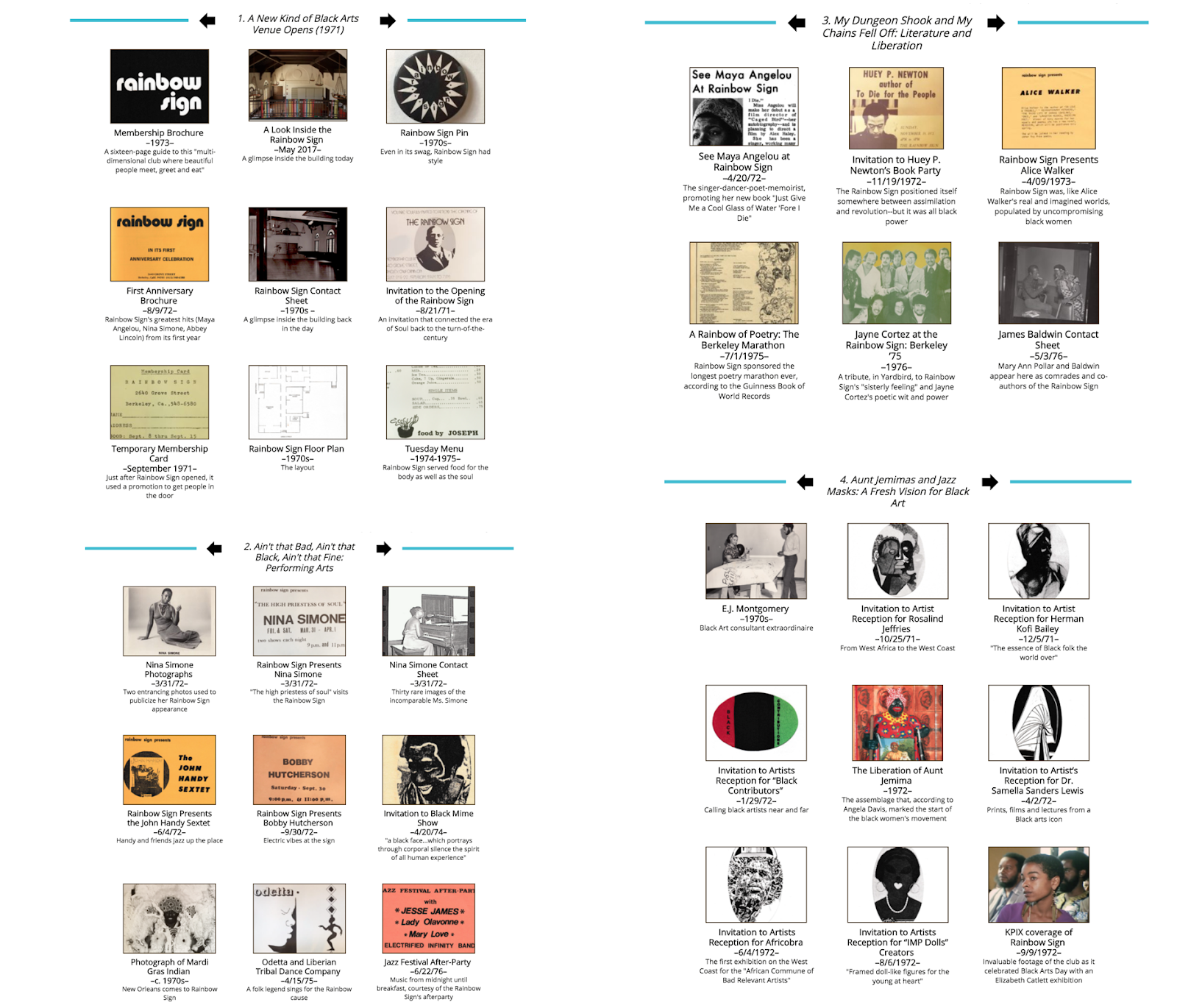

In its five-plus years of existence, Rainbow Sign often featured luminaries such as Maya Angelou, Elizabeth Catlett, Odetta, Nina Simone, and James Baldwin; equally, it nurtured emerging artists such Terry McMillan, Ntozake Shange, and Betye Saar (whose Liberation of Aunt Jemima—an artwork that Angela Davis has named as the origin point of the modern black women’s movement—was created for an exhibition there).3 All the while, it hosted a wide range of political figures—from African dignitaries to African-American leaders such as presidential candidate Shirley Chisholm; Warren Widener, Berkeley’s first black mayor; and Black Panther Huey Newton.4 The openness of Rainbow Sign’s programming meant that, at different moments, it took on different coloration. At times it looked like a social club for the emerging black middle class of the East Bay, as it sought to realize the 1970s form of the black clubwomen’s motto of “lifting as we climb.”5 At others, it served as a hospitable staging ground for the more transformative visions articulated by radical artists like Jayne Cortez, Bob Kaufman, Catlett, and Simone.

Despite the resurgence of historical work on black politics and art in the 1970s Bay Area, Rainbow Sign has yet to receive much critical attention.6 Whether because of its location (in Berkeley rather than Oakland), or because of its difficult-to-pin-down politics, or because of its multifaceted blend of politics and culture, it falls outside the scope of pioneering works on East Bay black politics in the 1970s such as Robert Self’s American Babylon and Donna Murch’s Living for the City.7 Meanwhile, the broader history of the Black Arts Movement has largely been told via figures who fit a particular profile: young, male, and militantly identified with the black working class—figures who speak to and for, as the language of the Black Panther Party would have it, the “brothers on the block.”8 Yet, as historians such as Brittney Cooper, Ashley Farmer and others have suggested, this period was also deeply enriched by the work of black women, who provided their own understanding of what the project of political and cultural liberation entailed.9

Rainbow Sign opens onto another front of black women’s activism in the age of Black Power—a front led by professionally successful black women, of a slightly older generation, who sought at once to elevate black culture, transform American politics, and provide mentorship to younger artists so that, rather than scuffling forever, they might build a career of art-making.10 In the Rainbow Sign, older strains of respectability politics were synthesized with an embrace of grassroots Black Nationalist organizing and Afrocentric aesthetics. We might see this fusion in the aesthetic of Rainbow Sign’s promotional materials: for the club’s opening, guests were “soulfully invited” to the event by an image of a dapper black man in turn-of-the-century coat, tie, and high collar. The club’s motto was “for the love of people”—not “for the love of the people” (which might contrast “the people” with “the elites,” in the manner that the Black Panther Party elevated “the lumpen”), and not “for the love of black people” (which would have underlined the center’s orientation toward the black community). With “for the love of people,” Rainbow Sign intimated that its founding principle was an all-accepting ethos of care and love.11

This ethos led Mary Ann Pollar to embrace the role of curator: Pollar was at once central to everything that transpired at her center and also a hidden structuring presence, orchestrating a community without seeming to wield the conductor’s baton. This was hidden work, performed by a now-hidden figure. Yet it’s also true that Pollar, with impressive self-awareness, gave an account of what she imagined that such curation could achieve. In Rainbow Sign’s “Background and Philosophy,” she meditated on how the design of the center could lead the black community to become “involved and enriched,” describing how its artist showcases would set in motion a virtuous cycle:

By providing this “showcase” we would fill several needs in this community. (1) The need of artists to show their works or talents and, most importantly, to do so outside the usual commercial setting…(2) We fill the need of a controlled situation wherein the promising artist could interact with the professional on a one to one basis. Third, and to us most important, we would have a place where young children could come and be influenced by people they regard as heroes.12

Pollar envisioned a neat multi-generational model of art in the black community—one that would bind children to their artist-heroes, the “promising artist” to the established “professional,” and all artists to an audience that would come together “outside the usual,” and often white- dominated, “commercial setting.” Rainbow Sign put that model into practice with aplomb over its five-year run, helping to launch the careers of an impressive number of figures while consolidating the careers of many others.

Recently, literary historian Margo Natalie Crawford has powerfully suggested that the “second wave” of the Black Arts Movement in the 1970s opened up the categories of black art-making in a manner that in our current moment feels particularly prophetic. Anything but hamstrung by a narrow sense of racial identity, BAM artists troubled blackness without worrying about the loss of blackness; celebrated and investigated what it felt like to “be” black as well as “become” black; and experimented with techniques of mixed-media, abstraction, and parody that tie them to contemporary writers ranging from Claudia Rankine and Harryette Mullen to Mat Johnson and Terrance Hayes. The work produced through Rainbow Sign—the artworks hung on its walls, and the music, dance and drama that unfolded on its stage—resonates strongly with Crawford’s characterization of the Black Arts Movement’s second wave. It brought together pride and irony, open-ended exploration and pointed critique. Meanwhile the social history of Rainbow Sign suggests the organizational energy and the curatorial spirit of care that rested at the foundation of this second wave, at least in the Bay Area and perhaps elsewhere. As more cultural historians come to appreciate the “long history of the Black Arts movement,” it is crucial that we acknowledge the women who birthed new organizational forms and helped give the Black Arts Movement its new surge of life in the 1970s.13

II. Beyond Figures: Digital Curation and the Promise of Non-Computational Methods within Digital History

If we have gauged our own efforts appropriately, the first section of this essay should be legible as history, in that it presents an argument about Rainbow Sign using the methods—narrative, citation of evidence, references to the relevant historiography—that are conventional in the profession. Less conventional, however, was the method by which we arrived at this argument: a blend of old-fashioned archival digging and of curation techniques tied to the affordances of digital media. If, as Cameron Blevins has proposed, digital history “has over-promised and under-delivered” in the realm of argument-driven scholarship because of its “love affair with methodology,” we would suggest that the problem lies, in part, with how we have tended to define the methodological tools specific to digital history.14

“We are infatuated with the power of digital tools and techniques to do things that humans cannot, such as dynamically mapping thousands of geo-historical data points,” Blevins continues. What is lost, we wonder, when digital history is largely defined through data-driven methods of computational analysis, mapping, and visualization? Our experience suggests that digital history would be wise to consider how other methods—less computation-driven but tied to digital media—can lay the foundation for fresh historical arguments. In our case, the method was the act of building a well-annotated, highly structured multimedia exhibition around a set of some fifty-plus primary sources, selected from many more.

In order to reconstruct the cultural work of Rainbow Sign’s Mary Ann Pollar, we needed in our case to become digital curators, which in turn meant sticking very close to our primary documents, keying into the spirit of Pollar’s enterprise, and modeling her own curatorial ethos anew.15

This digital archive was built through an honors undergraduate seminar in American Studies at UC Berkeley (“The Bay Area in the Seventies”), in which one of us (Scott) was the teacher and another one of us (Tessa) was a student, working with a fellow student (Max Lopez) on Rainbow Sign. The Rainbow Sign project was one of eleven such student-generated (and professor-guided) projects, spanning topics from the ecology movement and the disability rights movement to the desegregation of Berkeley’s public schools and the history of a pioneering queer resource center, incubated through two iterations of this small research seminar in 2017 and 2018.

Methodologically, the course asked students, first, to do the conventional work of a history research seminar: find a fresh set of primary sources and, through secondary reading, ask informed questions of those sources.16 Instead of producing the typical undergraduate research essay—a slimmed-down version of a scholarly article—students proceeded to build curated digital exhibitions, working in stages and from the primary sources outward. The site architecture enforced a certain scrupulousness. First came the annotation of primary sources, with each represented by a well-chosen thumbnail and tag line that encapsulated its point of interest.17 Next came the sorting of the larger set of primary sources into clusters of usually between three and nine—clusters which themselves needed to be ordered and also given a telegraphic but explanatory title. This clustering operation often proved quite difficult—and forced students to grapple with the fact that primary documents do not speak to one another until the historian puts them in dialogue. Last came the crafting of the framing essay, which built upon the narrative structured by the “clusters.” Our experience confirmed Michael Kramer’s insight about the productive strictures of the digital: rather than use computation to speed up analysis, the course used its tailored WordPress site to slow down thinking and to force attention toward the level of granular detail and to put pressure on the relation between evidence and argument.18

While abiding by the protocols of the historian, we have also sought, in our digital curation of the Rainbow Sign archive, to work in the spirit of Mary Ann Pollar. Just as she advertised Rainbow Sign as a “unique multi-dimensional club where beautiful people meet, greet and eat,” a center that was “open to all who are sympathetic to our Black orientation, cognizant of our vast diversity, and dedicated to quality achievement,” so we tried to create a convivial digital space that would be sharp in its design and unwavering in its hospitality to all. Alongside our presentation of primary documents, we aimed to offer analysis that was straightforward and precise. Our design aimed not to emphasize our own authority as gatekeepers of knowledge but to illuminate the process and even the delight of building a collective history. By bringing the original documents into the spotlight, we strove to equip site visitors to become curator-historians themselves—to meet us in the archive, as it were. Our format hopes, in the spirit of Rainbow Sign, to kindle curiosity, prompt diverse interpretations, and spur conversation rather than conversion.19

It is easy to downplay the analytical work of curation since it is the sort of “care work” that is often considered menial and gendered female. Curation, write the authors of Digital Humanities Manifesto 2.0 (2009), involves “custodial responsibilities with respect to the remains of the past as well as interpretative, meaning-making responsibilities with respect to the present and future.”20 Clearly they mean to praise curation, not bury it, but the phrase “custodial responsibilities” typically attaches to those pushing brooms, not tapping keyboards. In this context, we find the curatorial labor of Mary Ann Pollar particularly inspiring as a model of egalitarian and necessary cultural work. History easily forgets those who set the stage, invite the artists, welcome the public, and literally keep the lights on, but it is useful to recall that without them there is no stage, no public, and no lights. Digital history could well borrow some of the humility associated with the curator’s role, while learning better to draw from its considerable power.

Bibliography

Advertisement for Edward E. Niehaus Co. Ivory Chapel. Berkeley Daily Gazette, February 19, 1945, 13. https://newspaperarchive.com/berkeley-daily-gazette-feb-19-1945-p-13/.

Arguing with Digital History working group, “Digital History and Argument,” white paper, Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (November 13, 2017): https://rrchnm.org/argument-white-paper/.

“The Berkeley Revolution: A digital archive of one city’s transformation in the late-1960s and 1970s.” University of California, Berkeley. 2017-2019. http://revolution.berkeley.edu

Barber, Jesse. “Redlining: the history of Berkeley’s segregated neighborhoods,” Berkeleyside, September 20, 2018. https://www.berkeleyside.com/2018/09/20/redlining-the-history-of-berkeleys-segregated-neighborhoods.

Blevins, Cameron. “The Perpetual Sunrise of Methodology” (blog post). January 5, 2015. http://www.cameronblevins.org/posts/perpetual-sunrise-methodology/.

Campus Planning Office. Long Range Development Plan, University of California at Berkeley, Response to Comments on Jan. 1990 Draft Environmental Impact Report (University of California, Berkeley, 1990), 10.

City of Berkeley. “Proclamation of Nina Simone Day,” March 31, 1972, Rainbow Sign archive, private collection of Odette Pollar. http://revolution.berkeley.edu/mayors-proclamation-nina-simone-day/.

“Contact sheet, photographs of James Baldwin.” May 3, 1976. Rainbow Sign archive, private collection of Odette Pollar. http://revolution.berkeley.edu/james-baldwin-contact-sheet/.

Cooper, Brittney. Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Crawford, Margo Natalie. Black Post-Blackness: The Black Arts Movement and Twenty-First-Century Aesthetics. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Eubanks, Jonathan. “Contact sheet from Nina Simone performance at Rainbow Sign.” March 31, 1972. Rainbow Sign archive, private collection of Odette Pollar. http://revolution.berkeley.edu/nina-simone-contact-sheet/?cat=437&subcat=1.

Eubanks, Jonathan. “Contact sheet from Shirley Chisholm appearance at Rainbow Sign.” November 4, 1971. Rainbow Sign archive, private collection of Odette Pollar. http://revolution.berkeley.edu/shirley-chisholm-campaign-trail/?cat=437&subcat=4.

Farmer, Ashley D. Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Harris, Kamala. The Truths We Hold: An American Journey. New York: Penguin, 2019.

Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks. Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880-1920. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994.

“Invitation, book party for Huey P. Newton (sponsored by Mills College’s Black Student Union).” November 19, 1972. Rainbow Sign archive, private collection of Odette Pollar. http://revolution.berkeley.edu/huey-newton-book-party-flyer/.

Knight, Christopher. “Rashid Johnson at David Kordansky Gallery: Power, Production, Plus ‘Ugly Pots’.” Los Angeles Times, May 5, 2018. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-et-cm-rashid-johnson-20180505-htmlstory.html.

Kohl, Herb. Commentary, “Berkeley Experimental Schools” panel. Berkeley Historical Society. June 2, 2019.

Kramer, Michael J. “Writing on the Past, Literally (Actually, Virtually).” February 4, 2014. http://www.michaeljkramer.net/writing-on-the-past-literally-actually-virtually/.

Lopez, Max and Tessa Rissacher. “The Rainbow Sign.” The Berkeley Revolution. University of California, Berkeley, June 2017. http://revolution.berkeley.edu/rainbow-sign.

“Membership Brochure, Rainbow Sign.” 1973. Rainbow Sign archive, courtesy of Odette Pollar. http://revolution.berkeley.edu/rainbow-sign-membership-brochure/?cat=437&subcat=0.

McCurdy, Jack. “Berkeley’s School Integration Program Proceeds Smoothly.” Los Angeles Times, Sept. 2, 1968. A1, A8.

Murch, Donna. Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

“Odetta and Liberian Tribal Dance Company” flyer. April 15, 1975. Rainbow Sign Archive, courtesy of Odette Pollar. http://revolution.berkeley.edu/odessa-liberian-tribal-dance-company/?cat=437&subcat=1.

Presner, Todd, Jeffrey Schnapp, et al. “The Digital Humanities Manifesto 2.0.” University of California, Los Angeles. May 29, 2009. http://manifesto.humanities.ucla.edu/2009/05/29/the-digital-humanities-manifesto-20/#0.

Price, Electra. Interview by Max Lopez and Tessa Rissacher. Audio (mp3). San Leandro, CA. April 23, 2017. http://revolution.berkeley.edu/electra-price/.

Rainbow Sign archive (private archive in possession of Odette Pollar). Oakland, California.

“Rainbow Sign Background and Philosophy” (grant application supplement) c. 1973-1976. Rainbow Sign archive, Oakland, California.

Ramella, Richard. “The Rainbow Sign Can Use Some Help,” Berkeley Gazette, April 18, 1975. 14. http://revolution.berkeley.edu/assets/RainbowSignCanUseSomeHelp.png.

Ross, Linda. “Depicting Black Struggle.” The Berkeley Barb, April 11–17, 1975. http://revolution.berkeley.edu/assets/Depicting-Black-Struggle-e1493934839678.jpg.

Saar, Betye. “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” (assemblage, 11 3/4 x 8 x 2 3/4 in.), 1972. http://revolution.berkeley.edu/liberation-aunt-jemima/.

Self, Robert. American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

Smallwood, Bill. “See Maya Angelou at Rainbow Sign.” Oakland Post, April 20, 1972. http://revolution.berkeley.edu/see-maya-angelou-rs/?cat=437&subcat=2.

Smethurst, James. The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Spencer, Robyn C. The Revolution Has Come: Black Power, Gender, and the Black Panther Party in Oakland. Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

Taylor, Ula Yvette. The Promise of Patriarchy: Women and the Nation of Islam. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Thompson, Daniela. “Edward F. Niehaus: West Berkeley Stalwart.” Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association. 31 August 2009. http://berkeleyheritage.com/berkeley_landmarks/niehaus.html.

Notes

The authors wish to thank Max Lopez, Tessa Rissacher’s co-author on the original Rainbow Sign digital history project, whose contributions were essential to our understanding of Rainbow Sign. We also wish to thank Suzanne Smith and the anonymous reviewers at CRDH, whose comments on a draft of this essay helped us tighten its argument and expand its scope.

-

The building that Mary Ann Pollar rented to house Rainbow Sign had a telling history, as did the immediately surrounding area. 2640 Grove Street had been built in 1925 as the “Ivory Chapel” of funeral director Edward E. Niehaus, likely the son of Edward F. Niehaus, a West German immigrant, lumber magnate and Berkeley stalwart. The Niehaus mortuary featured a Spanish Colonial Revival design by architect James W. Plachek, who also designed important Berkeley civic buildings such as the city’s Central Library and North Branch Public Library.

In the 1940s, when large numbers of African-Americans were drawn to Berkeley because of jobs in East Bay war industries, Grove Street became an even sharper boundary separating white and non-white Berkeley, with blacks made aware through the 1950s, at least, that they were not welcome to buy real estate above Grove Street.

In an important reversal of the process of segregation, it was at a storefront office at 2554 Grove Street—less than a block from Rainbow Sign’s soon-to-be location—that the Berkeley Unified School District drew up its 1968 plan to desegregate the city’s elementary schools through organized busing. (Berkeley remains the only city that voluntarily drew up and embraced its own busing plan.) Just afterward, this storefront office hosted educational innovator Herb Kohl, who devised the paradigmatic “open school” (alternative high school) called Other Ways. Mary Ann Pollar appreciated that her Grove Street location placed her close to five local schools, including an elementary school, middle school and high school: “We want those children to short-cut through Rainbow Sign,” she said. Thus did the boundary between white and black Berkeley become the creative borderlands where projects of desegregation, especially at the youth level, were incubated and put into practice. Campus Planning Office, Development Plan, 10; Advertisement for Niehaus Co. Ivory Chapel, 13; Thompson, “Edward F. Niehaus”; Barber, “Redlining”; Kohl, “Berkeley Experimental Schools” panel; McCurdy, “Integration Program”; Ramella, “Rainbow Sign Can Use Some Help.” ↩ -

“Membership Brochure, Rainbow Sign.” ↩

-

Smallwood, “See Maya Angelou,” 18; Ross, “Depicting Black Struggle,” 17; “Odetta” flyer; Eubanks, “Contact sheet from Nina Simone”; “Contact sheet, photographs of James Baldwin”; Saar, “Aunt Jemima.” For Rainbow Sign sources, see Max Lopez and Tessa Rissacher, “Rainbow Sign” digital project, a component of The Berkeley Revolution. ↩

-

Eubanks, “Contact sheet from Shirley Chisholm”; City of Berkeley, “Nina Simone Day”; “Invitation, book party for Huey P. Newton.” ↩

-

On the activism and “politics of respectability” of the black club women’s movement, see Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent; Cooper, Beyond Respectability. ↩

-

While we detail below the lack of attention paid to Rainbow Sign by historians and literary critics, we are also happy to note that, since the publication of the “Rainbow Sign” digital project on the Berkeley Revolution site in the summer of 2017, there has been snowballing attention to the center. In May of 2018, LA Times art critic Christopher Knight mentioned it as a key context for New York-based artist Rashid Johnson’s acclaimed “Rainbow Sign” exhibition (Knight, “Rashid Johnson”). In February of 2019, the Oakland Museum of California opened a re-designed “Black Power” installation that featured the center, and currently the de Young Museum in San Francisco is looking to spotlight Rainbow Sign as they customize the exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power (opening November 2019) around the arts of the Bay Area. In the realm of politics, US Senator Kamala Harris drew upon the primary documents in the digital project and made the Rainbow Sign central to the first chapter of her memoir The Truths We Hold, published in January 2019. Observing that her time there as a child shaped her sense of cultural and political possibility, the Berkeley-raised politician noted that Rainbow Sign “was where I learned that artistic expression, ambition, and intelligence were cool. It was where I came to understand that there is no better way to feed someone’s brain than by bringing together food, poetry, politics, music, dance, and art.” Harris, The Truths We Hold, 16–19. ↩

-

Self, American Babylon; Murch, Living for the City. ↩

-

In his groundbreaking The Black Arts Movement, literary historian James Smethurst nicely sketches how the campuses of UC Berkeley, San Francisco State, and Merritt College became hotbeds of activism and black cultural production. Yet when he turns his attention off-campus, Smethurst focuses his narrative on cultural centers such as San Francisco’s Black House, the short-lived and contentious project that brought together Black Panther scribe Eldridge Cleaver and the radical playwrights Ed Bullins and Marvin X. ↩

-

Cooper, Beyond Respectability; Farmer, Remaking Black Power; Spencer, The Revolution Has Come; Taylor, The Promise of Patriarchy. ↩

-

Pollar and the ten women who served on Rainbow Sign’s board were from a middle generation—younger than race radicals such as Ella Baker (b. 1903) and Angelo Herndon (b. 1913) whose perspectives were centrally shaped by the labor struggles of the Great Depression, and older than Baby Boomer figures like Huey Newton (b. 1942) and Angela Davis (b. 1944). A descendant of a line of Baptist preachers, Mary Ann Pollar herself was born in a Texas border town in 1927, and took a degree in labor education from Roosevelt College in Chicago in the late 1940s; through the 1950s and 1960s she worked for the Bay Area Urban League while establishing herself as music promoter through her work with acts from Bob Dylan and Odetta to Curtis Mayfield and Simon and Garfunkel. The Rainbow Sign board was populated by black women who had broken professional barriers, including TV newscaster Belva Davis, and East Bay education leaders Mary Jane Johnson and Electra Price. ↩

-

This fusion between radical and respectable can also be read in the aspirational and care-oriented language that its founders used to evoke its project. Rainbow Sign board member Electra Price described the center as “a model. It said: this is what it would look like if people got their act together.” Price Interview. ↩

-

“Rainbow Sign Background and Philosophy.” ↩

-

Crawford, Black Post-Blackness, 1-17. ↩

-

Blevins, “Perpetual Sunrise of Methodology.” ↩

-

The larger place of archival curation within digital history is well-sketched in the white paper which emerged from the 2017 Arguing with Digital History working group: “Digital History and Argument.” ↩

-

The Rainbow Sign project drew upon an archive of six dusty boxes, stashed in the basement of the Oakland home of Mary Ann Pollar’s daughter Odette—boxes that had never before been opened by her. Time constraints limited the amount of material we were able to scan for the project, so we opted to include ephemera with striking visual appeal, such as the invitations to art exhibits, or items with rich informational content, such as the brochures. ↩

-

Once readers navigate to the page for a primary source, they are presented with a longer caption—anywhere between a few sentences and a few paragraphs—placing the item in context with other documents or relevant historical material. Research for the content of these captions often involved cross-referencing the periodical record, oral histories and secondary sources. ↩

-

Kramer, “Writing on the Past.” ↩

-

Just as the multiplicity of Rainbow Sign’s rooms and functions invited cross-pollination—those there for lunch might take in an art show; concert attendees might browse through a chapbook of poetry—the diverse “rooms” of our site work to inspire dialogue between the art objects, and between the performers. Our framing commentary exists to enrich context, but seeks as well to set itself clearly in the space of the frame. The formal affordances of the website, meanwhile, allow us to offer a layered experience of exploration. Music once performed at Rainbow Sign can play over the speakers while one browses; images of rooms then and now can fill in the mental picture of a poetry reading described in an article. ↩

-

Presner, Schnapp, et al. “The Digital Humanities Manifesto 2.0.” ↩

Authors

Tessa Rissacher,

Department of English, University of California, Berkeley, thetessalady87@gmail.com,