What’s on History?

Tuning In to Conspiracies, Capitalism, and Masculinity

Abstract

Introduction

Following the success of Ken Burns’ The Civil War and the subsequent boom of historical programming on cable television in the 1990s, media historian Gary Edgerton made the bold claim that “television is the principal means by which most people learn about history today.”1 Despite the continued popularity of museums and online resources, this assertion remains largely true. However, the historical programming now presented on television is no longer dominated by the “biographies and quasi-biographical documentaries” of decades past.2

While PBS and a few other outlets continue to produce educational programming that presents historical content rooted in archival research and scholarly expertise, such as Reconstruction: America After the Civil War (2019), other networks such as History (formerly The History Channel) have shifted to more financially profitable programming that is only loosely based on historical content and gives little regard to topical representativeness and nuanced interpretation.3 As Edgerton recently noted, historical programing is now an “entirely new and different kind of programming altogether” that comprises a spectrum of quality from “comprehensive, complex, and penetrating to trash TV.”4 Ann Gray and Erin Bell have argued that these changes are the result of larger industry forces such as the intensification of competition, the fragmentation of the audience, branding, and celebrity culture which are driving content creation. The “search for ‘niche’ audiences has shaped the requirements of history programmes in relation to choice of periods and topics considered to be attractive to these target audiences.”5 As Brian Taves explains, “The History Channel’s bedrock support is considered to be men, middle-aged and older; hence the emphasis on programming dealing with war, weapons, and technology, especially during its weekend lineup, as a counteroffering to sports broadcasting.”6 Many of these pressures, in addition to a host of new factors, also apply to the creation of content for streaming services as well.7

These programming changes have not come without criticism by scholars and media critics who have called out History’s production of inaccurate, fabricated, and purposefully ambiguous content that continues to move further away from historical scholarship and closer to conspiracy narratives and reality television.8 As Nancy Dubuc, the former CEO of A+E Networks and the person credited with transforming the network, has stated, “at the end of the day we’re [History] not an education resource. We’re an entertainment brand.”9 While History is not the only scholastic television network to move away from research-based educational programming (see Discovery Channel, formerly The Discovery Channel, and TLC, formerly The Learning Channel), its authoritative presence and substantial viewership makes this shift of pressing importance to public historians and educators. As of 2020, History reached 380 million homes worldwide and much of its content is now accessible via Hulu, Netflix, YouTube, and its own streaming service History Vault.10

Scholars have argued that film and television, and by extension History and its programming, play an important role in historical knowledge production and the present shaping of collective memory, especially in relationship to how audiences engage with historical content in everyday life.11 As historian Leon Litwack reminds us, “over the past century, the power of historians and filmmakers to influence the public, to reflect and shape attitudes and popular prejudices, has been amply demonstrated, often with tragic consequences.”12 If History is in fact transgressing the boundary of infotainment and is directly impacting our social frameworks, what kind of discourses are circulating on the channel? How do those discourses shape the historical understanding of the audiences who are consuming content from sources that are framed as authoritative?

This article employs a mixed methods and interdisciplinary approach to analyze thirty consecutive days of 2018 programming aired on History in the United States. To critically understand the themes and messages of History’s programming both in aggregate and as individual shows, we supplemented a close reading of the four most frequently aired shows with topic models generated from the episode titles and descriptions. We argue that the majority of the network’s aired programming is reality television in the guise of historical content. By filming the day-to-day operations of small businesses or micro industries, such as alligator hunting, the network is able to capture the drama and interpersonal conflict that fuels the interests of television audiences. This “raw” footage is then edited together with short historical trivia asides that create a veneer of educational merit. Not only has History fully embraced reality television, it is profiting off of a problematic orientation to the factual and evidence-based framework that humanistic and scientific inquiry is built upon. We argue that History supplements its conspiratorial programming with shows that reproduce a narrow conception of masculinity that emphasizes whiteness, manual labor, patriotism, and the mythic frontier situated within a capitalist framework. By entangling this masculinity narrative with a nostalgic, decontextualized, and meritocratic understanding of the American Dream, History caters to an older, predominantly white male demographic and offers programming that aligns with and legitimizes their worldview.

Methods

To create the corpus, we collected episode titles and descriptions from History’s website for all programs aired from May 15, 2018 through June 13, 2018: 905 total programs with 510 unique episodes. We then used word frequency counts and topic modeling to analyze the compiled corpus. Topic modeling is a method of computational analysis, often referred to as distant reading, that uses word co-occurrences to analyze the themes or topics of a text corpus.13 From the corpus, the model generates a specified number of topics and provides a breakdown of what percentage of each topic is contained within a particular text, or in this case, episode title and description. In this way, the themes of History’s programming across shows can be seen in aggregate. To improve the output of the model, we removed duplicated episodes and pruned the vocabulary, omitting proper names and other words unique to the corpus, such as “rick,” “chum,” “rip,” “episode,” and “troy,” that skewed the model.14 After creating several topic models, we concluded that twelve topics was the optimal number for the corpus.

Results & Analysis

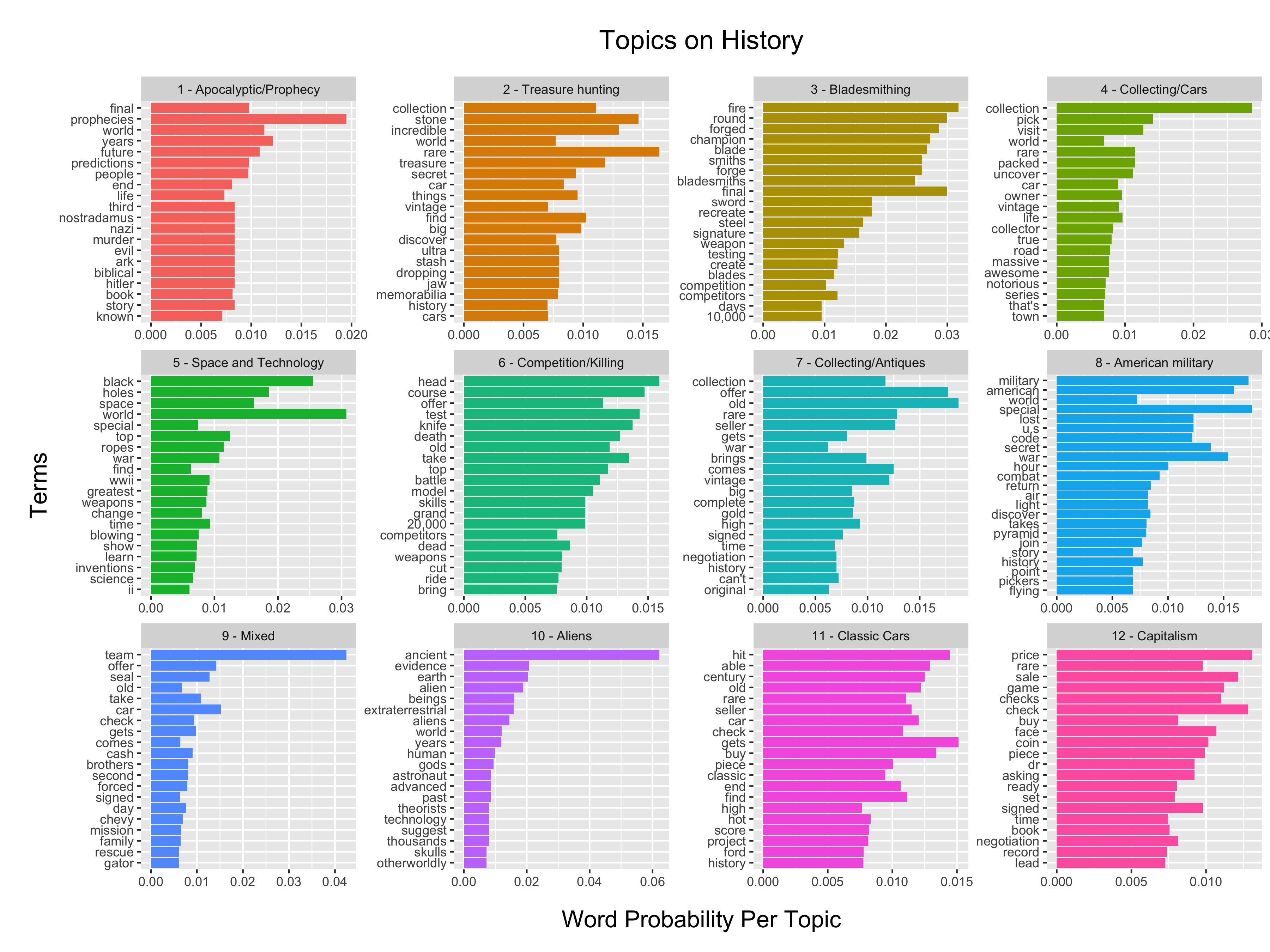

The results of the topic model showed a general lack of historic themes. Figure 1 depicts a topic model with twelve topics and displays the top twenty most significant words associated with each topic.

Based on the content or words of each topic, we assigned labels to each:

- Apocalyptic/Prophecy

- Treasure hunting

- Bladesmithing

- Collecting/Cars

- Space and Technology

- Competition/Killing

- Collecting/Antiques

- American military

- Mixed

- Aliens

- Classic Cars

- Capitalism

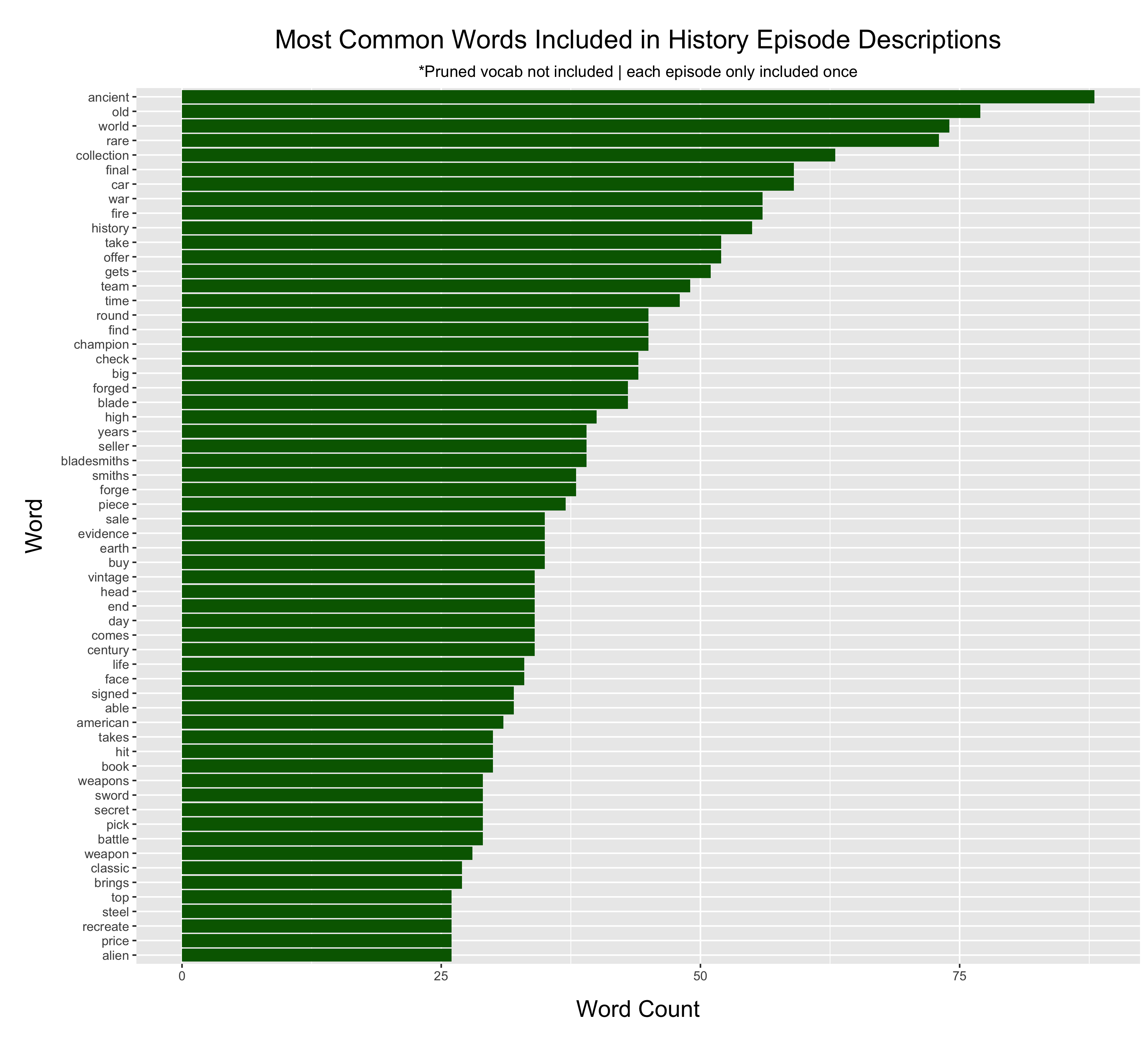

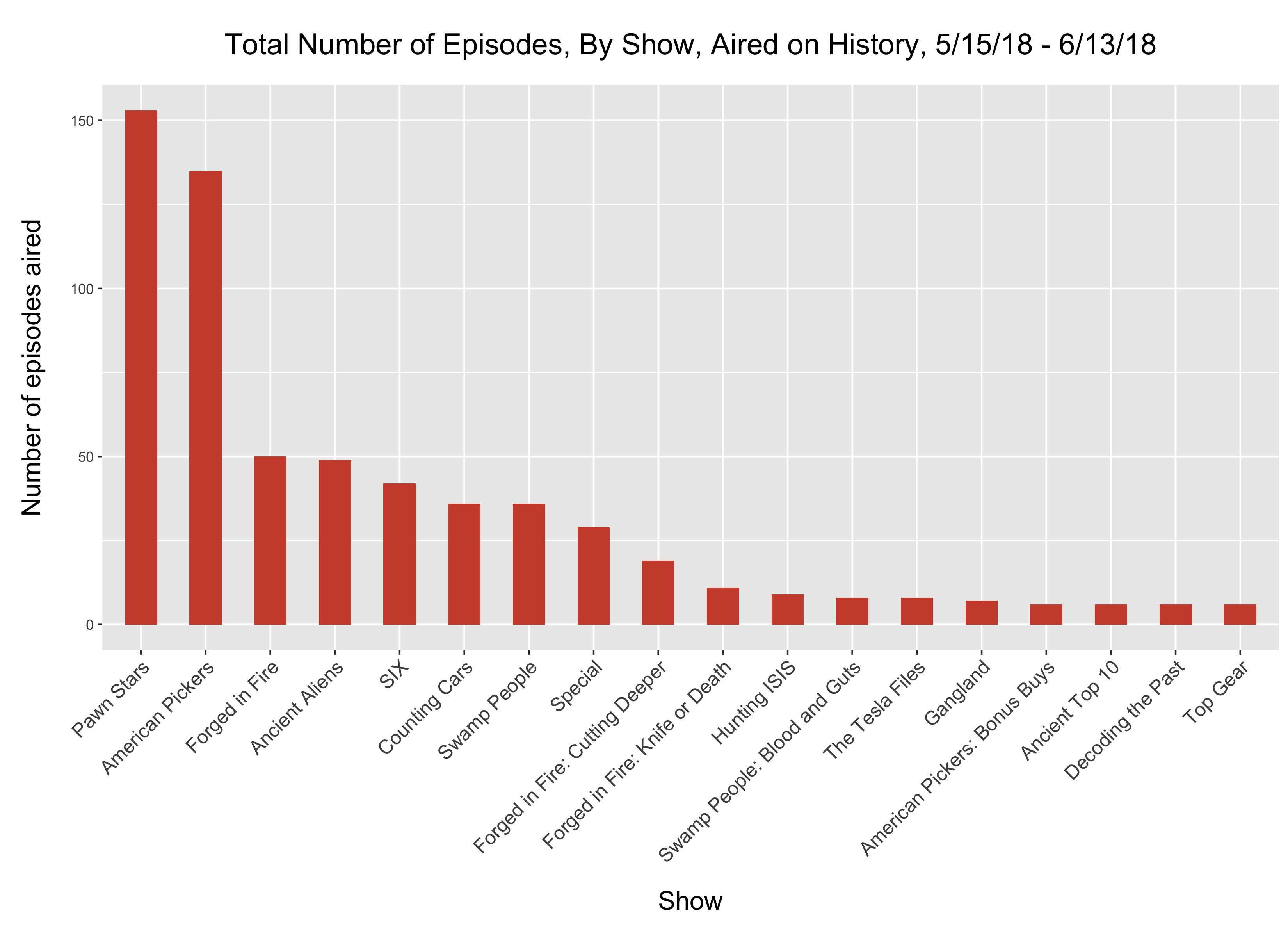

To gain an understanding of the overall prevalence or frequency of these topics on History, not just their mere existence or inclusion in the topic model, we counted the number of times a particular word appeared in an episode title or description (see figure 2). After examining the models, we performed a close textual analysis of several episodes of the most frequently aired programs (see figure 3). The close readings of these shows revealed not only the themes of conspiracy and capitalism but an underlying thread of masculinity.

Conspiracy

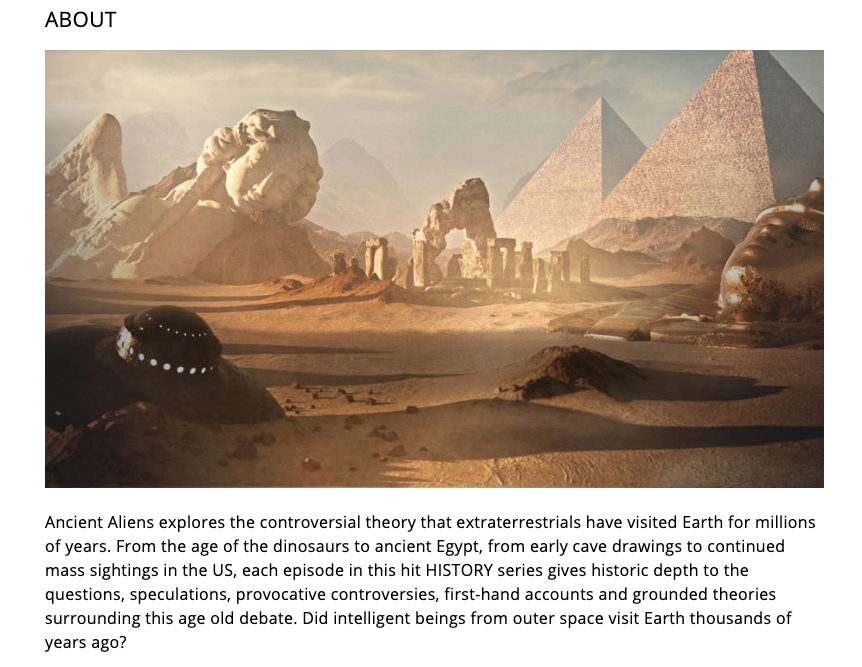

The most prominent topic in the model consisted of aliens, prophecies, and speculative content. Ancient Aliens (49 episodes) was the most frequently-aired and emblematic program of this topic in the sample. The premise of Ancient Aliens is anything but novel; rather, it is part of the long tradition of alternative archeology or pseudoarchaeology. The fascination with the possibility of extraterrestrial ancestors can be traced back to the Victorian Era and the early 20th century works of H.P. Lovecraft.15 By the 1920s, many of the topics and theories of modern alternative archeology or pseudoarchaeology were already present including:

giants; ancient space travelers; magic as occult science and wisdom; druids; megaliths; poor “sounds alike, is alike” linguistics; secret texts in unknown languages; a particular interest in the Aryan race; lost continents; “looks alike, is alike” comparisons between places like Egypt, the Maya homeland, Peru, and Easter Island; myth as history; and a high handed disdain for foolish, materialist scientists and benighted religious leaders.16

These same themes can be seen in the questions posed by Ancient Aliens (see figure 4).

| Selected Ancient Aliens Questions |

|---|

| Could giant ancient drawings found etched into the desert floor be part of an ancient alien code? |

| Could black holes exist not just in outer space, but here on Earth? And if so, could Earth’s Black Holes have caused strange disappearances and other inexplicable phenomena for centuries? |

| What is the meaning behind secret messages found throughout Washington, D.C.? |

| Did America’s Founding Fathers know something about ancient aliens that the general public did not? And if so, could this knowledge have been incorporated into the symbols, architecture, and even the founding documents of the United States of America? |

| If ancient aliens visited Earth, were they responsible for catastrophes, wars and other deadly disasters to control the fate of the human race? |

| The story of the Great Flood sent by deities to destroy civilizations exists in many prehistoric cultures. There are ancient descriptions of extraterrestrial battles that caused wide-scale destruction, and even reports of UFOs lurking in the shadows of recent natural disasters. The Book of Revelations [sic] and the Dead Sea Scrolls describe a future apocalyptic battle between good and evil that will destroy our world. Are these ancient texts proof that aliens are hostile and planning a violent return? Or might they be our saviors, ensuring our survival as a species during times of devastation? |

| Hindu scripture describes an enormous flying creature called a Garuda that shook the ground when it landed on Earth. Is it possible that this monster was actually a misinterpreted alien craft? |

| Are hybrids like the Centaur, the Minotaur and Medusa just mythical creatures of fantasy—or could these ancient depictions of terrifying monsters have been the result of advanced extraterrestrial transplantation procedures? |

| What if, as Ancient Astronaut theorists believe, there is evidence to connect Bigfoot with an alien species that once visited Earth in the distant past? |

Each episode of Ancient Aliens consists of a carefully selected group of what are called “ancient astronaut theorists” who attempt to explain historical and archeological questions about ancient civilizations through the past visitation of extraterrestrial beings (see figure 5). The lack of credentialed and respected archeologists on this show is a hallmark of pseudoarchaeology. As Jeb Card explains, “Anyone willing to wear the old symbols of preprofessional archaeology can claim the archaeological legacy and its mythic social currency even if their ideas or methods have no significant tie to archaeological practices past or present.”17

Through the examination of archeological sites and artifacts, these ancient astronaut theorists attempt to bring credibility to their often unsupported, fantastical, and extraterrestrial explanations. By continuously posing often unanswerable questions without any conclusive answers and cherry-picking evidence, the show erodes the basis for proof and understanding that scientific and humanistic inquiry are founded upon, thus promoting the acceptance of highly unlikely and unsupported theories as legitimate possibilities. The testimony of ancient astronaut theorists and their ideas is constructed as just as legitimate as that of professional archeologists and their peer-reviewed research.18 In some respects, the ancient astronaut theorists are portrayed as more legitimate because of their lack of academic training that would have prevented them from seeing the bigger picture. As Card has pointed out, the one unifying theme of alternative archeology is its “opposition to professional mainstream archeology and, more broadly, science.”19

By providing adherents to alternative archaeology or pseudoarchaeology with a platform to promote their ideas, History legitimizes their perspectives and threatens to undermine or delegitimize the research methods and conclusions of professional archeologists. As Evan Parker argues, “the proliferation of these [infotainment] programs becomes problematic when we consider that they are purported to be educational and lay claim to authenticity and scientific truth…Even if audiences grasp the inauthenticity of such programs, it does not diminish many of the negative externalities generated by the scientific claims made by hosts.”20 Even the Smithsonian has taken notice. In a review of Ancient Aliens, Brian Switek opines that “What results is a slimy and incomprehensible mixture of idle speculation and outright fabrications which pit the enthusiastic ‘ancient alien theorists,’ as the narrator generously calls them, against ‘mainstream science.’ I would say ‘You can’t make this stuff up,’ but I have a feeling that that is exactly what most of the show’s personalities were doing.”21

Alternative archeology has already contributed to the proliferation of conspiracy narratives and the undermining of scientific truth. Conspiracy theorists such as Alex Jones and Jim Marrs cite Lovecraft’s “Call of Cthulhu” as inspiration for their work.22 As Card cautions, “Alternative archaeology can be a major vector for spreading old racist ideologies into the present.”23 Sarah Bond has similarly argued that Ancient Aliens and pseudoarcheology has a racial dimension whereby practitioners deny the agency of non-Western peoples and diminish their accomplishments.24

The questioning of professional research is not limited to the discipline of archeology. As Card has argued, “the explosion of cable television and Internet media, the declining government funding of educational media, and the resulting privatization and outsourcing of documentary production replaced academic and specialist media figures with telegenic presenters of mysterious themes.”25 With this changing economic environment, History found the construction of ambiguous, unresolved narratives to be a profitable endeavor with shows such as Ancient Aliens, The UnXplained, Haunted History, History’s Mysteries, UFO Files, Conspiracy?, MonsterQuest, Nostradamus Effect, and Decoding the Past among others.26

Capitalism and Masculinity

In addition to the conspiratorial content of pseudo-documentaries, the topic model also indicates the prevalence of content derived from History’s reality television programming. Capitalism tied to a narrow conception of masculinity that emphasizes whiteness, manual labor, patriotism, and the mythic frontier was the most prominent theme in the sample and wove many of the topics together. Some media scholars attribute the rise in popularity of programming featuring dangerous occupations, survival skills, treasure hunting, and entrepreneurship to the twenty-first century masculinity crisis in the U.S. and a perceived loss of societal power and privilege among white men who adhere to a construction of masculinity rooted in labor.27 Since its debut, History has emphasized capitalism with programming such as the failed launch of The Spirit of Enterprise and the miniseries docudrama The Men Who Built America (2012), which focuses on titans of industry such as Vanderbilt, Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Ford.28 This tradition of celebrating fortunes made through capitalism, albeit on a smaller scale, is carried on in the two most aired shows during the thirty-day sample period, Pawn Stars which aired 153 times, and American Pickers and American Pickers: Bonus Buys, which aired 141 times combined (see figure 3).

Pawn Stars, a hit show on History since 2009, is a reality television program that features the Gold & Silver Pawn Shop in Las Vegas and follows “three generations of the Harrison family” as they “jointly run the family business.”29 These men are depicted as no nonsense, well-networked business experts who are concerned with making a profit. In the opening of Pawn Stars, Rick Harrison states, “at my shop, family comes first and money comes second…depending on who you ask.” A typical scene in Pawn Stars consists of someone entering the shop with an item, the Harrisons or family-friend Chumlee verifying its authenticity (often with an outside appraiser’s help), a price negotiation, and finally a sale of the item.30

The second most aired show, American Pickers, also highlights History’s construction of masculinity and was in large part comprised of the topics “collecting” and “treasure hunting.” American Pickers, which premiered in 2010, is a reality television show that features two Midwesterners, Mike Wolfe and Frank Fritz, as they travel the rural U.S. in search of Americana to restore and resell at their antique shops. History’s description of the show begins with, “[t]his isn’t your grandmother’s antiquing” and states that Mike and Frank are “on a mission to recycle America, even if it means diving into countless piles of grimy junk or getting chased off a gun-wielding homeowner’s land.”31 On the show, Mike and Frank are usually in search of vintage cars, oil cans, signage, and memorabilia tied to U.S. patriotism and industrial labor. The show often features sellers who are older, white men in rural America.

The overall framing of the show and of the sellers reinforces Mike and Frank’s personas as “everyday, hardworking guys” and “expert buyers.” The show presents the two men as “good guys” who are trying to make fair deals with sellers and who respect the stories and memories that may be associated with the objects.32 American Pickers repackages the antiquing genre, as featured in programs such as PBS’s Antiques Roadshow, into a manly quest for rusty gold or “mantiques.” As Madeleine Shufeldt Esch explains, “where Antiques Roadshow focuses on traditional appraisal techniques, provenance and conservative valuations from licensed experts, the new appraisal TV formats defy images of stuffy antique shops or high-end auction houses.” In this way, the show “emphasizes the rugged physicality of picking and the macho business tactics of brokering deals while narratively excluding traditionally feminine aspects of collecting and the feminized sphere of antiques retail.”33 Mike and Frank are able to momentarily keep industrial white nostalgia alive for themselves, sellers, and audiences as they rummage through barns and piles of “junk.”

Coming in a distant third for most-aired programming on History was the reality television competition Forged in Fire, along with its related series Forged in Fire: Cutting Deeper and Forged in Fire: Knife or Death (80 total episodes). The Forged in Fire series contribute to the construction of masculinity on History and include topics such as competition/killing, capitalism, and bladesmithing. In the show, bladesmiths forge iconic weapons from metal that are judged by a panel of experts to determine the winner of $10,000 (see Figure 6). The show repackages the popular television format of cooking and singing competitions in a way that emphasizes violence and rewards lethality.

The forge itself evokes imagery of gritty, sweaty, and tiresome work in the U.S. popular imagination. Contestants on the show, predominately men, are featured frantically heating, hammering, pressing, and grinding steel as sweat drips off of their faces in front of a glowing fire. Judges test the strength and durability and sharpness of the weapons in addition to a final “kill test” involving animal carcasses and ballistic dummies. Brandon Weigel explains that the show is a “callback to our country’s height as an industrial powerhouse, when red-blooded American men could make a good living using their hands, and so much of what we bought proudly said ‘Made in the U.S.A.’”34

Related to the themes of capitalism and masculinity were a number of occupational themed programs, such as Swamp People, where hunters kill and sell alligators.35 While Swamp People dominated the number of episodes aired during the sample, it has previously shared this occupational programming genre with shows such as Appalachian Outlaws, Ax Men, Ice Road Truckers, and Mountain Men. Two other popular categories consisted of scripted dramas36 and shows about automobiles.37

Conclusion

The themes that weave this sample of History’s programming together are conspiracies, capitalism, and masculinity; these topics are over-represented on History. In keeping with the network’s long-standing association with war-themed programming, military history remains a prominent theme on the channel, but it only occupied a small percentage of aired programming in the sample. While History moves further and further away from scholarly content, it continues to enjoy a scholarly authority regarding the past. History’s authoritative presence has been reinforced through educational partnerships such as “History in the Classroom” and its collaboration with and/or financial support of museums and historical associations such as the National Park Service, the Smithsonian, the Library of Congress, Mount Vernon, the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration, the Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum, the National Council for Public History, the American Historical Association, and the Organization of American Historians among others. These associations legitimize the brand name as a trustworthy and respected source of historical information.38

Given History’s popularity, it is important for scholars of all disciplines to critically examine what messages are being sent and received through the seemingly authoritative medium of History and other cable television networks such as Discovery Channel, TLC, Smithsonian, and National Geographic. While streaming services, such as Netflix, have consciously attempted to respond to the changing economic, social, and political landscape in the U.S. and the demand for better representation by offering a variety of programming with more inclusive narratives, television networks often have to adapt to older and less diverse cable/satellite audiences to remain profitable.

In a historical period of divisive politics and “alternative facts” of the Trump administration, discourse production concerning conspiracy theories and white masculinity on History is of pressing importance. As the following description for a recent season of Swamp People shows, History’s narrow conception of masculinity is not going anywhere:

As the new alligator hunting season begins, the swampers’ very way of life is under siege. The alligator hunting industry is on the verge of collapse due to the lowest prices in history. Some buyers aren’t purchasing anything this year, and there’s talk that the wild alligator industry might disappear completely. Facing bigger obstacles than ever before, Troy calls a meeting of the patriarchs from the swamp’s main gator hunting families…39

While scholarly historical programming is becoming harder to produce and find on cable television, Ken Burns reminds us that “we mustn’t throw the medium out, turn away, or surrender its great power to those disingenuous people for whom it is merely the tool of some temporal or financial end.”40 The impact of television programming is too important to ignore.

Bibliography

Bacevich, Andrew J. “History That Makes Us Stupid.” Chronicle of Higher Education. November 1, 2015. http://www.chronicle.com/article/History-That-Makes-Us-Stupid/233971.

Becker, Anne. “The History Channel Teams Up with the Library of Congress.” Broadcasting & Cable. April 12, 2008. https://www.broadcastingcable.com/news/history-channel-teams-library-congress-32110.

Blei, David M., Andrew Y. Ng, and Michael I. Jordon. “Latent Dirichlet Allocation.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 3 (2003): 993–-1022.

Bond, Sarah E. “Pseudoarchaeology and the Racism Behind Ancient Aliens.” Hyperallergic. November 13, 2018. https://hyperallergic.com/470795/pseudoarchaeology-and-the-racism-behind-ancient-aliens/.

Brendan, Christie. “History in the Making: Inside the First 25 Years of One of Cable’s Top Brands.” Realscreen (blog). January 22, 2020. https://realscreen.com/2020/01/22/history-in-the-making-inside-the-first-25-years-of-one-of-cables-top-brands/.

Buchanan, Burton P. “Portrayals of Masculinity in The Discovery Channel’s Deadliest Catch.” In Reality Television: Oddities of Culture, edited by Alison F. Slade, Amber J. Narro, and Burton P. Buchanan, 9–-28. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2014.

Bunch III, Lonnie G. “How Lonnie Bunch Built a Museum Dream Team.” Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-lonnie-bunch-built-museum-dream-team-1-180973132/.

Burns, Ken. “Four O’Clock in the Morning Courage.” In Ken Burns’s the Civil War: Historians Respond, edited by Robert Brent Toplin, 153–-83. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Card, Jeb J. Spooky Archaeology: Myth and the Science of the Past. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2018.

Colavito, Jason. The Cult of Alien Gods: H.P. Lovecraft and Extraterrestrial Pop Culture. Prometheus Books, 2005.

Deery, June. “Mapping Commercialization in Reality Television.” In A Companion to Reality Television, edited by Laurie Ouellette, 11–-28. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2017.

George Washington’s Mount Vernon. “Discovering George Washington.” http://www.mountvernon.org/the-estate-gardens/museum/education-center-galleries/.

Edgerton, Gary. “Television as Historian: An Introduction.” Film & History 30, no. 1 (2000): 7–-12.

Edgerton, Gary R. “The Past Is Now Present Onscreen: Television, History, and Collective Memory.” In A Companion to Television, 2nd ed., edited by Janet Wasko and Eileen R. Meehan, 79–-103. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2020.

Esch, Madeleine Shufeldt. “Picking Through History: ‘Mantiques’ and Masculinity in Artifactual Entertainment.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 20, no. 5 (2017): 509–-24.

ESI Design. “ESI Design Brings Sweeping New Dynamic and Interactive Exhibits to Ellis Island’s New National Immigration Museum.” May 12, 2015. https://esidesign.com/esi-design-brings-sweeping-new-dynamic-and-interactive-exhibits-to-ellis-islands-new-national-immigration-museum/.

Fox News. “Rick Harrison on ‘Life, Liberty & Levin’: Capitalism Is ‘Survival of the Fittest.’” August 5, 2018. http://insider.foxnews.com/2018/08/05/rick-harrison-life-liberty-levin-capitalism-survival-fittest.

Gillette, Felix. “A+E Networks CEO Nancy Dubuc, the Duck Whisperer.” Bloomberg.com. June 20, 2013. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-06-20/a-plus-e-networks-ceo-nancy-dubuc-the-duck-whisperer.

Gomez-Aguilar, Antonio. “Content Bubbles: How Platforms Filter What We See.” In Handbook of Research on Transmedia Storytelling, Audience Engagement, and Business Strategies, edited by Victor Hernandez-Santaolalla and Monica Barrientos-Bueno, 238–-350. Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2020.

Grainge, Paul, ed. Memory and Popular Film. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003.

Gray, Ann, and Erin Bell. History on Television. London: Routledge, 2013.

Harvey, Sylvia. “Broadcasting in the Age of Netflix: When the Market Is Master.” In A Companion to Television, edited by Janet Wasko and Eileen R. Meehan, 105–-28. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2020.

History. “American Pickers: About.” History, 2018. https://www.history.com/shows/american-pickers/about.

History. “Pawn Stars: About.” History, 2018. https://www.history.com/shows/pawn-stars/about.

History. “Swamp People: About,” 2018. https://www.history.com/shows/swamp-people/about.

Knapp, Alex. “An Archaeologist Watches the History Channel and Questions the Part About the Aliens.” Forbes. September 19, 2011. https://www.forbes.com/sites/alexknapp/2011/09/19/an-archaeologist-watches-the-history-channel-and-questions-the-part-about-the-aliens/#2ee1787f3e65.

Kutler, Stanley I. “Why the History Channel Had to Apologize for the Documentary That Blamed LBJ for JFK’s Murder.” History News Network. April 7, 2004. https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/4504.

Landsberg, Alison. Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

Lipsitz, George. Time Passages: Collective Memory and American Popular Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990.

Litwack, Leon F. “Telling the Story: The Historian, the Filmmaker, and the Civil War.” In Ken Burns’s the Civil War: Historians Respond, edited by Robert Brent Toplin, 119–-40. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

National Museum of American History. “National Museum of American History’s New Exhibition Examines 250 Years of American Military Conflicts.” October 20, 2004. https://americanhistory.si.edu/press/releases/national-museum-american-history%E2%80%99s-new-exhibition-examines-250-years-american.

O’Connell, Libby Haight. “The History Channel and History Education.” Perspectives on History 33, no. 7 (October 1995). https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/october-1995/the-history-channel-and-history-education.

Palmer, Gareth. “The Wild Bunch: Men, Labor and Reality Television.” In A Companion to Reality Television: Theory and Evidence, edited by Laurie Ouellette, 247–-63. Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2014.

Parker, Evan A. “The Proliferation of Pseudoarchaeology through ‘Reality’ Television Programming.” In Lost City, Found Pyramid: Understanding Alternative Archaeologies and Pseudoscientific Practices, edited by Jeb J. Card and David S. Anderson. Tuscaloosa: University Alabama Press, 2016.

Popp, Richard K. “History in Discursive Limbo: Ritual and Conspiracy Narratives on the History Channel.” Popular Communication 4, no. 4 (2006): 253–72.

Schone, Mark. “Media Circus: All Hitler All the Time.” Salon. May 8, 1997. https://www.salon.com/1997/05/08/media_90/.

McCann Systems. “Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History - Washington D.C.” June 28, 2010. https://www.mccannsystems.com/audio-visual-projects/smithsonian-natural-museum-of-history/.

Switek, Brian. “The Idiocy, Fabrications and Lies of Ancient Aliens.” Smithsonian.com. May 11, 2012. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-idiocy-fabrications-and-lies-of-ancient-aliens-86294030/.

Taves, Brian. “The History Channel and the Challenge of Historical Programming.” In Television Histories: Shaping Collective Memory in the Media Age, edited by Gary R. Edgerton and Peter C. Rollins, 261–-81. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2001.

Chief Marketer. “The History Channel Partners With Intrepid Museum.” July 7, 2004. https://www.chiefmarketer.com/the-history-channel-partners-with-intrepid-museum/.

Trapani, William C., and Laura L. Winn. “Manifest Masculinity: Frontier, Fraternity, and Family in Discovery Channel’s Gold Rush.” In Reality Television: Oddities of Culture, edited by Alison F. Slade, Amber J. Narro, and Burton P. Buchanan, 183–-201. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2014.

Weigel, Brandon. “This Will Kill: History Channel’s ‘Forged in Fire’ and American Economic Anxiety.” City Paper. July 5, 2017. <www.citypaper.com/film/bcp-070517-screens-forged-in-fire-20170705-story.html>.

West, Zach. “The History Channel? Historical Content by Show.” Cracked.com. June 30, 2010. http://www.cracked.com/funny-5720-the-history-channel/.

Wright, Robert. “The Way We Were? History as ‘Infotainment’ in the Age of History Television.” In The River of History: Trans-National and Trans-Disciplinary Perspectives on the Immanence of the Past, edited by Peter Farrugia, 35–-57. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2005.

Journal of Digital Humanities 2, no. 1 (2012). http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/2-1/.

Notes

The authors would like to thank the editors and staff of CRDH, the three peer reviewers, and the attendees of the Lincoln’s Unfinished Work conference for their feedback and support. We would also like to thank Peter Eisenstadt, Amanda Regan, and Eric Gonzaba who provided generous feedback on drafts.

-

Edgerton, “Television as Historian,” 7. ↩

-

Edgerton, 7. ↩

-

Smithsonian, HBO, Netflix, and even ESPN have started producing engaging and insightful documentaries and historical dramas. History has recently made an attempt to include more substantive programs such as Washington (2020) and Grant (2020). For more on the profitability of reality television programming see Deery, “Mapping Commercialization in Reality Television.” ↩

-

Edgerton, “The Past Is Now Present Onscreen,” 82–-83. ↩

-

Gray and Bell, History on Television, 10. ↩

-

Taves, “The History Channel,” 261. ↩

-

Harvey, “Broadcasting in the Age of Netflix”; Gomez-Aguilar, “Content Bubbles.” ↩

-

Bacevich, “History That Makes Us Stupid”; Knapp, “An Archaeologist Watches”; Kutler, “Why the History Channel Had to Apologize”; Schone, “Media Circus”; Switek, “Ancient Aliens”; West, “The History Channel?”; Taves, “The History Channel.” ↩

-

Gillette, “A+E Networks CEO Nancy Dubuc.” ↩

-

Brendan, “History in the Making.” ↩

-

Edgerton, “Television as Historian”; Taves, “The History Channel”; Landsberg, Prosthetic Memory; Grainge, Memory and Popular Film; Lipsitz, Time Passages. ↩

-

Litwack, “Telling the Story,” 122. ↩

-

Blei, Ng, and Jordon, “Latent Dirichlet Allocation”; Journal of Digital Humanities 2, no. 1 (2012). ↩

-

The full list of customized stop words can be found in the accompanying code. ↩

-

Colavito, The Cult of Alien Gods; Card, Spooky Archaeology. ↩

-

Card, 15. ↩

-

Card, 15. ↩

-

Popp, “History in Discursive Limbo.” ↩

-

Card, Spooky Archaeology, 259–60. ↩

-

Parker, “Pseudoarchaeology,” 150, 155. ↩

-

Switek, “Ancient Aliens.” ↩

-

Card, Spooky Archaeology, 251. ↩

-

Card, 267. ↩

-

Bond, “Pseudoarchaeology.” ↩

-

Card, 263. ↩

-

Popp, “History in Discursive Limbo.” ↩

-

Trapani and Winn, “Manifest Masculinity”; Buchanan, “Portrayals of Masculinity”; Palmer, “The Wild Bunch.” ↩

-

Wright, “The Way We Were?”; Taves, “The History Channel.” ↩

-

History, “Pawn Stars: About.” ↩

-

Rick Harrison goes beyond the confines of his History timeslots to celebrate capitalism. In a recent interview with Fox News’ Life, Liberty & Levin, Harrison stated that capitalism is the ‘survival of the fittest’ and that ‘in the end everyone has a better life because of it,’ relying on an example of the watch-making business in the 1850s to support his claim. Harrison used the interview as an opportunity to promote libertarianism, his support of Donald Trump, and his personal success story in relation to the American Dream. Harrison noted his lower-middle class background, his self-education, and his father’s strong work ethic meanwhile condemning government regulation and socialism. Harrison’s appearance on Fox News and the blending of his on and off-screen personalities promotes a meritocratic understanding of success and connects the ideological messages of both networks. ↩

-

History, “American Pickers: About.” ↩

-

Esch, “Picking through History.” ↩

-

Esch, “Picking through History,” 510. ↩

-

Weigel, “This Will Kill.” ↩

-

Swamp People is an occupational reality television series that follows alligator hunters, primarily in Louisiana, on their quest find, kill, and sell alligators. ↩

-

Six (2017–2018), which was cancelled after two seasons, was the most-aired scripted drama in the sample. Six depicts the lives of Navy SEAL Team Six members both at home and abroad. Many of the plotlines focus on the rescue or saving of some individual. Six is part of History’s growing lineup of scripted dramas that include the successful historical fiction show Vikings (2013-2020), the more recently debuted Knightfall (2017-2019), and the new series Blue Book (2019-2020). These scripted historical dramas are becoming a more important part of History’s business model. ↩

-

A substantial amount of programming focused on automobiles in which shows such as Counting Cars (36 episodes), Top Gear (6 episodes), and Truck Night in America (2 episodes) were included in the sample. Counting Cars (2012–), a spin-off of Pawn Stars, is a reality television series that follows Danny “The Count” Koker, who “walks, talks and breathes classic American muscle cars,” and his crew as they restore and customize classic cars and motorcycles at Count’s Kustoms. With shows such as Counting Cars, History is contributing to a larger theme of nostalgia for old objects and ideas encompassed in shows such as American Restoration, Pawn Stars, and American Pickers. Top Gear (2010–2016), based on the BBC original, and Truck Night in America (2018–), a reality competition show that features trucks and jeeps, focus on the customization, performance, and limits of various vehicles. ↩

-

“National Museum of American History’s New Exhibition”; “Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History - Washington D.C.”; “Discovering George Washington”; “ESI Design Brings Sweeping New Dynamic”; Bunch III, “How Lonnie Bunch Built a Museum Dream Team”; Becker, “The History Channel Teams Up with the Library of Congress”; “The History Channel Partners With Intrepid Museum”; O’Connell, “The History Channel and History Education.” ↩

-

History, “Swamp People: About.” ↩

-

Burns, “Four O’Clock in the Morning Courage,” 177. ↩

Appendices

Authors

Joshua Catalano,

Department of History, Clemson University, catala4@clemson.edu,