Silent No More

Women as Significant Political Intermediaries in Ottoman Algeria

Abstract

Introduction

In 1724, two Ottoman governors combined forces and set out to bring the rebellious Algerian tribes to heel. In the eastern province of Constantine, they successfully took the mutinous Henanecha tribe by surprise. In the midst of defeat, Sheikh Bou Aziz prepared 8,000 head of cattle and goods to turn over to the Ottoman conquerors. Before he could deliver the property, however, his daughter Euldjia mounted her horse and rallied both men and women to attack the Turkish army. Together, the Henanecha drove the Turks into a hasty retreat and took the Ottoman lieutenant governor captive.1 Songs and oral traditions of the Henanecha recorded in the mid-nineteenth century still celebrated her heroism more than a century after her bold action saved the community.2 Euldjia is not the only remarkable Algerian woman, however.

While the history of Ottoman Algeria remains understudied, the history of Algerian women during this time period is practically unknown. Extant scholarship focuses almost exclusively on male officials in the Ottoman administration, effectively ignoring the larger socio-political context in which they operated.3 Over the course of nearly 300 years, as Ottoman and non-Ottoman governors struggled to suppress the recalcitrant clans of the eastern province of Algeria and sustain control, Algerian women proved invaluable partners in those efforts. After the mid-seventeenth century, most Ottoman officials married into a local family as one of the surest ways to establish their legitimacy among the Algerian elite. Ironically, the Sultan had banned the very unions that maintained Ottoman sovereignty in Algeria, but due to its increasingly marginalized position within the empire, officials in the regency were able to stretch beyond the confines of official policy. Most studies of Ottoman Algeria focus on masculine forms of political power. In contrast, this study contends that local women served as arbiters of Ottoman administrators’ right to rule in Algeria. Through their acceptance or denial of imperial officials’ marriage proposals, Algerian women conferred power or marked the suitor as unworthy of high office. Therefore, women played a significant role in shaping Ottoman-Algerian social politics and maintaining Ottoman sovereignty.

The few extant fragments of knowledge from Ottoman Algeria emerge from French and Arabic chronicles of the governors, travel narratives, and consular records.4 Through text mining to extract named and unnamed entities, and social network visualization to illustrate their relationships, unnamed women’s spectral presence may be represented despite their absence in the archival record. 5 These kinship connections and the sub-communities to which they give rise can be meaningfully investigated quantitatively using social network analysis measures, such as betweenness centrality scores. By examining these quantitative measures, we learn more about both named and unnamed women’s positions within the structure of Ottoman-Algerian society. Through an analysis of the individual lives, relationships and underlying structure that make up the Ottoman-Algerian network in Constantine between 1567 and 1837, I argue that Algerian women were essential intercultural mediators and conduits to power.

This study is also part of a wider historiography that explores how the intimate aspects of life, particularly sex and marriage, have played a significant and explicit role in imperial politics and policies since the sixteenth century.6 Consequently, the methods described herein may be used in widely disparate contexts, from webs of dynastic and elite relationships in China or Renaissance Europe to kinship networks in Dutch Java, as well as among Native Americans and European settlers in North America.7 The paired processes of text mining relational data and analyzing the resulting network allow scholars to recover the social positions and roles of both named and unnamed women, Indigenous and enslaved peoples, and others who are largely absent from predominantly elite, masculine, and colonizer-centric archives.8

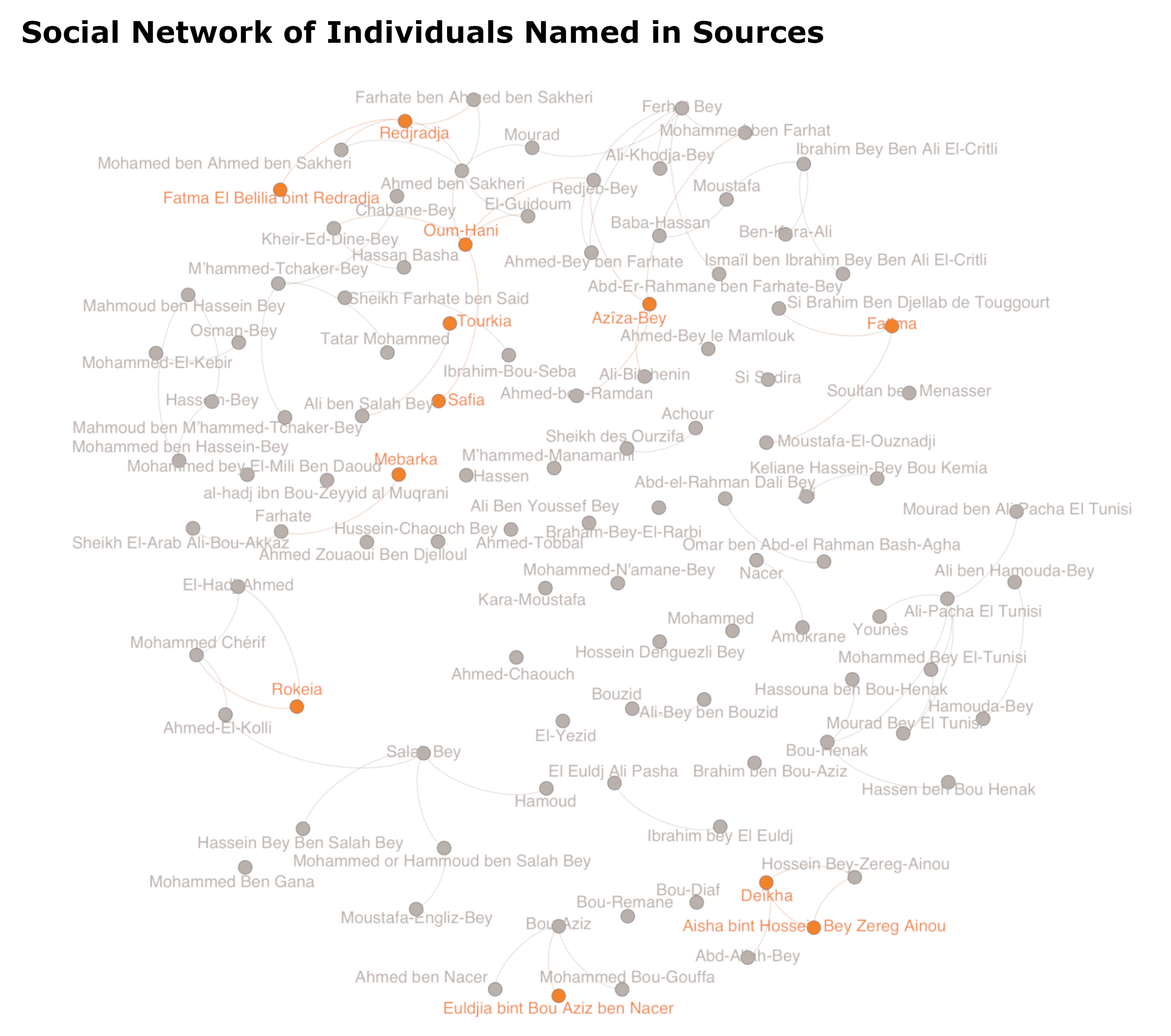

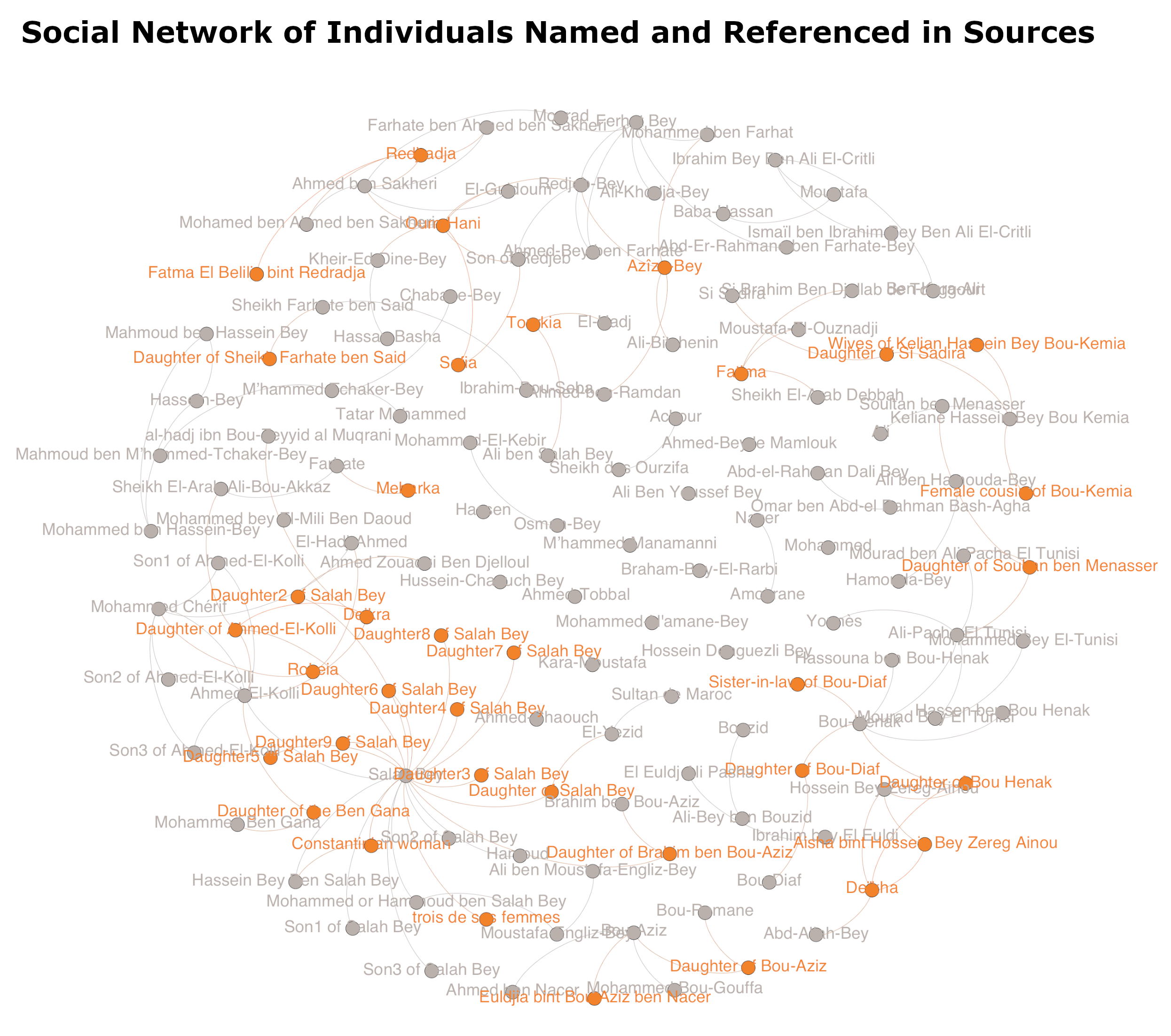

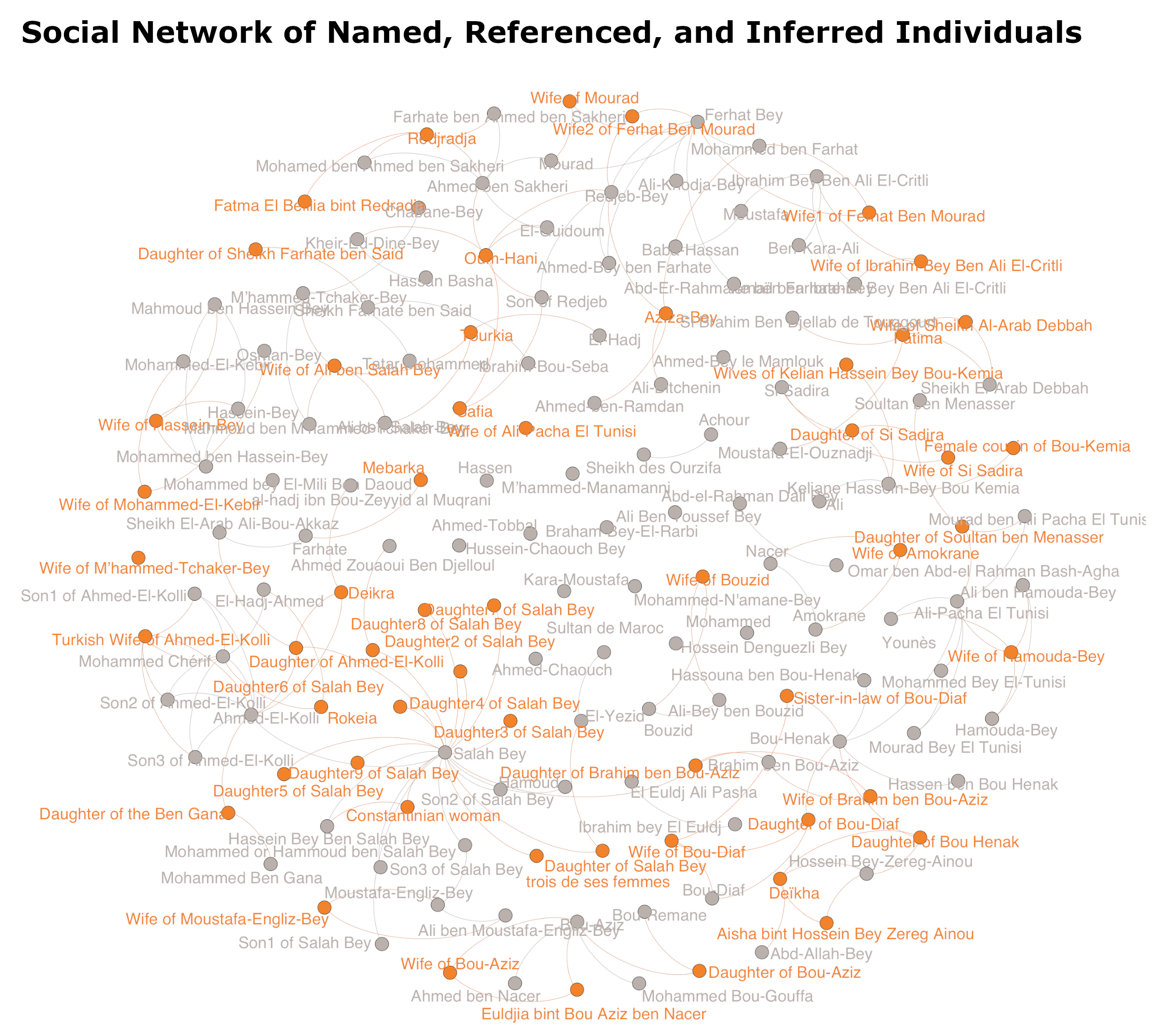

With a data set as complete as available sources allowed, I produced a series of three network visualizations and statistics for the most expansive graph to study the socio-political world of Ottoman Algeria. The first network image (shown in figure 1) depicts only individuals named in the records; the second graph (shown in figure 2) incorporates individuals who were not named but were explicitly referenced; and the final graph (seen in figure 3) includes individuals whose existence we inferred through the extant relationships in our data set. For instance, if a father-son relationship appeared in the documents, a woman had to be involved in order to bring that son into the world, so another node was added for the woman and linked to both the known father and son in the edges list.

Number and Proportions of Individuals in the Social Network Graphs by Gender and Identification Type

| Gender | Named | Referenced (% = Named + Referenced) | Inference (% is cumulative) | Row Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 93 (89%) | 11 (74%) | 0 (65%) | 104 |

| Women | 12 (11%) | 24 (26%) | 19 (35%) | 55 |

| Column Totals | 105 | 35 | 19 | 159 |

By adding individuals who are referenced but unnamed and those whose existence we may infer, we observe both an absolute and relative growth in the number and proportion of women in the social network. This process sheds light on both the social positions and kinship relations of many women whose names were not recorded. This is not merely a numbers game. The more people we can accurately represent in the graph, the better sense we have for the structure of relationships and the relative positions of men and women of various ethnicities in the society under consideration. It is this structure that we can meaningfully explore with network analysis.

Critical Considerations

An examination of Ottoman-Algerian social networks in the period prior to the French invasion, sheds light on the ways in which women, marriage, and kinship connections legitimated Ottoman rule, but these insights come with a number of caveats. On the one hand, we must remember that network visualization collapses timelines, which may lead to false conclusions. On the other, due to the nature of our source materials, adding time to these graphs would reveal more about the availability or scarcity of data rather than present a complete picture of the extent of intermarriage in each time period. Although this paucity of sources is an important aspect of the story of Algerian women’s marginalization in the archive, it does not shed light on their lived experience or roles in society, which is the present study’s objective.9

What social networks and their quantitative measures cannot tell us is as important as what they can. Although we can make educated guesses about the daily pursuits and experiences of the women in these graphs, without additional source materials, we cannot know what they thought about their marriages, politics, relations with their neighbors or any other topic in which we might be interested. In its very name, data visualization, promises to render things—people, identities, relations, etc.—visible, legible, and therefore knowable. Nevertheless, to see is not necessarily to know; data visualization reveals certain kinds of information, but it occludes others. It may even recapitulate the violence of the past by reducing people to numbers and objects. In light of this risk, it is important for scholars to offer humanistic readings of our data and source materials. By finding and highlighting the human experiences represented in our charts, we honor the fact that the numbers represent real, often marginalized, lives.

Betweenness Centrality and Women’s Positions in Ottoman-Algerian Society

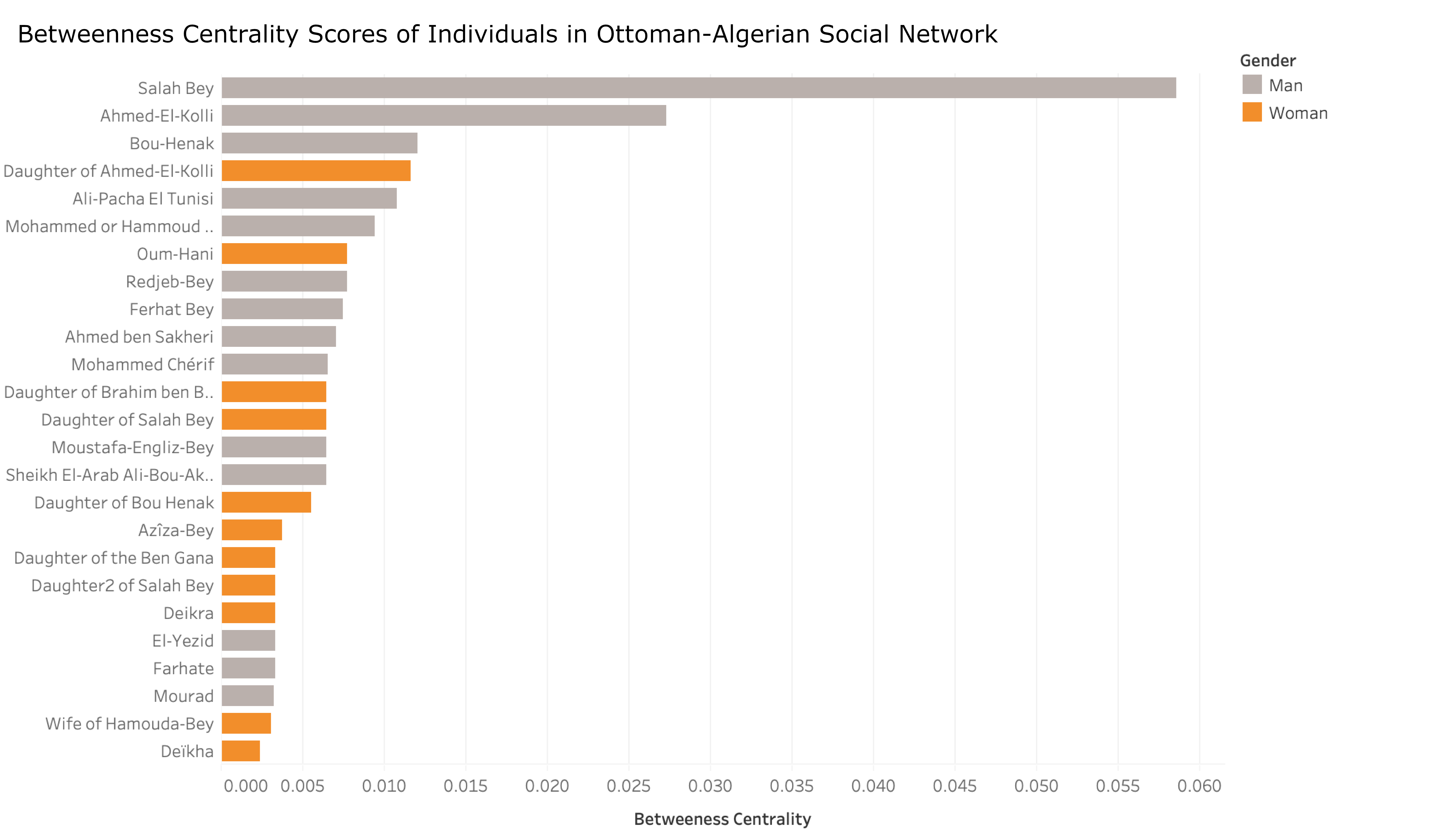

Kinship connections can be meaningfully investigated quantitatively using social network analysis measures. Betweenness centrality scores are particularly informative because they highlight the individuals who served as essential bridges between people, family units, and socio-political cliques. Technically, betweenness centrality is a measure of the number of shortest paths that travel through a node.10 Therefore, those with the highest rankings forged and maintained links between Ottoman officials and local families, bolstering Ottoman sovereignty in this frontier province. Imperial officers depended on these connections both to govern effectively and for their own safety and security while in office. Of the top twenty-five individuals, ranked by betweenness centrality, eleven (forty-four percent) are women. This proportion of women to men is much higher than one would expect by chance, given that women account for only thirty-five percent of the individuals in the graph. Furthermore, of these eleven women, seven of them are unnamed but explicitly referenced in the documents.

Marriages between Ottoman administrators and local women not only forged alliances between the officials and Algerian elites, but also to former governors as well.11 This is, in part, why so many women appear among the top individuals ranked by betweenness centrality scores, as seen in figure 4. Generations of interconnections formed powerful Ottoman-Algerian indigenous ruling families, through which, access to local power was transmitted through women, rather than solely from father to son (see Deikha’s story below). Much like the royal women in Istanbul, Algerian women and their mixed-ethnicity daughters became guardians of Ottoman sovereignty through their various roles as brides, wives, mothers, and counsellors for their husbands. Marriages between Ottoman officials and local women served as one of the surest avenues to power for ambitious men. Such marriages were a seal of approval for officials newly assigned to the eastern province, and provided Ottoman administrators access to local political and military networks. What is more, with their knowledge of local customs, hierarchies, and tribal relations, locally-born women became advisors and translators for their Ottoman husbands. Through their relationship with imperial administrators, Algerian women served as caretakers of Ottoman sovereignty at the very edge of empire.

A woman’s consent was, therefore, an essential ingredient in the Ottoman recipe for hegemony in Algeria. This is no more apparent than when consent was withheld. Toward the end of his tenure, Governor Salah Bey (r. 1771–1792) sought to consolidate support in his province and therefore needed the backing of the dominant tribes. In this effort, Salah Bey contracted an agreement with Sheikh Brahim ben Bou Aziz to marry Brahim’s daughter to formalize their alliance. When the moment arrived for the bridal procession to depart for Constantine, the bride-to-be refused to leave her quarters, pleading with her father to break off the engagement. At last, giving in to her tearful entreaties, the sheikh acquiesced and sent a messenger to deliver the unfortunate news.12 The rejection of Brahim’s daughter had dire consequences for the governor. Without these essential allies, Salah Bey was assassinated a year later.

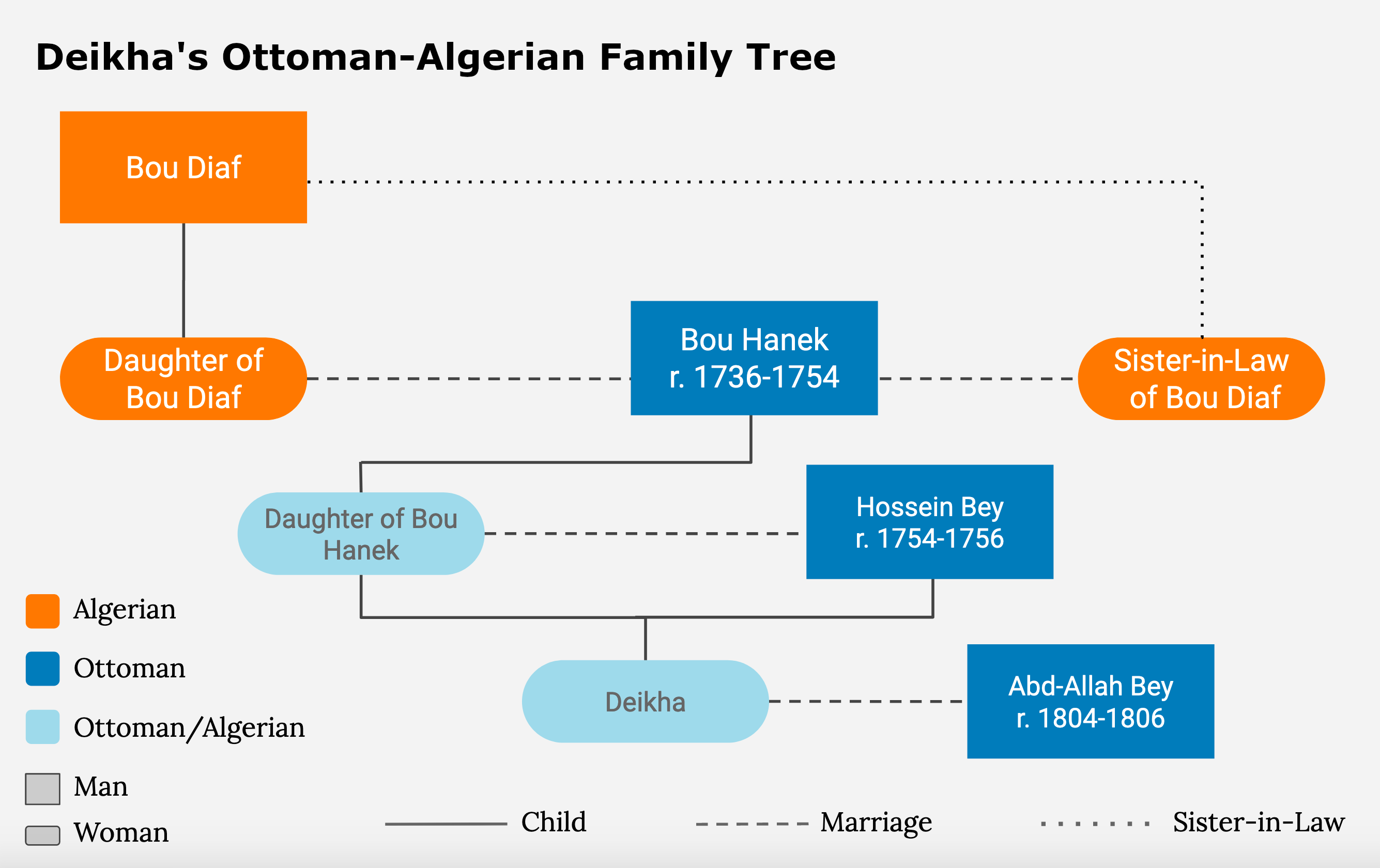

Through marriage, local elite women and their mixed-ethnicity daughters brought subsequent generations of officials into the blended Ottoman-Algerian political elite. In the early eighteenth century, Ottoman General Bou Hanek (r. 1736–1754) married into a powerful Algerian family and established a mixed Ottoman-Algerian household. When one of his daughters, unnamed in the sources, came of age, Bou Hanek arranged her marriage to his lieutenant governor, Hossein. Through this union, Bou Hanek anointed his successor. Like his father-in-law before him, Hossein agreed to the marriage of his own daughter, Deikha, to Abd-Allah Bey, an influential Ottoman official who became governor in 1804.

Deikha may be exceptional in that she is named in the sources and ranks in the top third of women by betweenness centrality, but the counsel she provided as the wife of a provincial governor was not unique.13 Her story reveals the ways in which locally-born women served as cultural translators and counsellors for Ottoman officials. Deikha was known for her energy, wisdom, and diplomacy. Like other elite women who married Ottoman officials, Deikha would have been well educated, both literate and numerate, and well prepared to manage a large household.14 As Hossein Bey’s daughter and Abd-Allah’s wife, Deikha capitalized on her family’s connections and cultivated advantageous relationships with Ottoman officials, Constantine’s bourgeoisie, and rural sheikhs. Her deft social skills and political acumen also won her the support and admiration of Abd-Allah’s council who sought her advice when facing thorny questions of governance. Each woman’s willingness to enter into the proposed marriages legitimated their Ottoman husbands in the eyes of the Algerian community. The example set by Bou Hanek, his Algerian wives, and mixed-ethnicity daughters led to the creation of a powerful Ottoman-Algerian family that influenced provincial politics for nearly a century.15

Conclusion

The network graphs depicted above show more than family trees. They demonstrate the interconnected nature of the composite Ottoman-Algerian society that developed in Constantine after the region became an Ottoman imperial province in the early sixteenth century. Analyzing these networks computationally offers significant insight into the structure of this society. Through marriage to imperial administrators, local women connected Algeria to the Ottoman Empire, legitimized their husbands’ authority in the province, and bore children who embodied the tensions of empire—neither fully Turkish, nor fully Algerian. Both Algerian women and their mixed-ethnicity daughters were key links in the chain that bound Algeria to the Ottoman Empire.

Social network analysis of Ottoman Algerian society complicates the masculine picture of Ottoman imperial governance and suggests that women were key mediators between the imperial administration and the local population. Previous scholarship has only examined male roles in household formation and political ascendance, but the data gathered and examined in the social networks above show how marriages between local women and imperial administrators were essential to a man’s path to the governorship and to the maintenance of Ottoman sovereignty in early modern Algeria.

Bibliography

Al-ʿAntarī, Ṣāliḥ Ibn Muḥammad. Farīdah manīsah [sic] fī ḥāl dukhūl al-Turk balad Qusanṭīnah wa-istīlāʾihim ʻalā awṭānihimā, aw, Tāʾrīkh Qusanṭīnah. Edited by Yaḥyā Bū ʿAzīz. Algeria: Dīwān al-Maṭbūʿāt al-Jāmiʿiyyah, 1991.

Arvieux, Laurent d’. Mémoires du chevalier d’Arvieux. Vol. 5. Paris: C.J.B. Delespine, 1735.

Barr, Juliana. Peace Came in the Form of a Woman: Indians and Spaniards in the Texas Borderlands. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Benhazer, Maurice. “La Jeanne d’Arc des Hanencha.” L’Afrique du Nord illustrée: journal hebdomadaire d’actualités nord-africaines: Algérie, Tunisie, Maroc. January 8, 1927. Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Droit, économie, politique, JO-50607. Bibliothèque Francophone Numérique. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k57832223.

Brooks, James. Captives & Cousins: Slavery, Kinship, and Community in the Southwest Borderlands. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

DuVal, Kathleen. “Indian Intermarriage and Métissage in Colonial Louisiana.” William and Mary Quarterly 65, no. 2 (April 2008): 267–304. https://doi.org/10.2307/25096786.

Eskridge, Caryne. “Illinois Culture, Christianity and Intermarriage: Gender in Illinois Country, 1650–1763.” (Undergraduate Honors Thesis, William and Mary, 2010. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/674.

Feraud, Laurent-Charles. “Les Harar.” Revue africaine : journal des travaux de la Société historique algérienne, no. 105 (1874): 191–236.

Fuentes, Marisa. Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018.

Gaïd, Mouloud. Chronique des beys de Constantine. Algeria: Office des publications universitaires, 1978.

Gutiérrez, Ramón A. When Jesus Came, the Corn Mothers Went Away: Marriage, Sexuality, and Power in New Mexico, 1500–1846. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991.

Hurtado, Albert L. Intimate Frontiers: Sex, Gender, and Culture in Old California. (Histories of the American Frontier). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999.

James, Carolyn. “Marriage by Correspondence: Politics and Domesticity in the Letters of Isabelle d’Este and Francesco Gonzaga, 1490-1519.” Renaissance Quarterly 65, no. 2 (Summer 2012): 321–52. https://doi.org/10.1086/667254

Kallander, Amy Aisen. Women, Gender, and the Palace Households in Ottoman Tunisia. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014.

Kane, Maeve. “All One People and Under One King: Social Network Analysis of Ethnic Separation in the Mixed-Race Fort Hunter Congregation, 1734–1746.” University of California Irvine, 2018. http://maevekane.net/wmq-uc/.

Klein, Lauren F. “The Image of Absence: Archival Silence, Data Visualization, and James Hemings.” American Literature 85, no. 4 (December 2013): 661–88. https://doi.org/10.1215/00029831-2367310.

Loualich, Fatiha. La famille à Alger: XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles: parenté, alliances et patrimoine. Saint Denis: Éditions Bouchène, 2016.

McGowan, Margaret M. Dynastic Marriages, 1612/1615: A Celebration of the Habsburg and Bourbon Unions (European Festival Studies: 1450–1700). Farnham: Ashgate, 2013. https://doi.org/10.4324%2F9781315578347.

Menchi, Silvana Seidel, ed. Marriage in Europe, 1400–1800. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442625488.

Mercier, Ernest. Histoire de Constantine. Constantine, Algeria: J. Marle et F. Biron, 1903.

Merouche, Lemnouar. Recherches Sur l’Algérie à l’époque Ottomane. Bibliothèque d’histoire Du Maghreb. Paris: Bouchene, 2002.

Missoum, Sakina. Alger à l’époque Ottomane: La Médina et La Maison Traditionnelle. Aix-en-Provence, France: Edisud, 2003.

Molho, Anthony. “Deception and Marriage Strategy in Renaissance Florence: The Case of Women’s Ages.” Renaissance Quarterly 41, no. 2 (Summer 1988): 192–217.

Morrissey, Robert Michael. “Kaskaskia Social Network: Kinship and Assimilation in the French-Illinois Borderlands, 1695–1735.” William and Mary Quarterly 70, no. 1 (2013): 103–46. https://doi.org/10.5309/willmaryquar.70.1.0103.

Murray, Jacqueline, ed. Marriage in Premodern Europe: Italy and Beyond (Essays and Studies, 27). Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2012.

O’Brien, Jean M. Dispossession by Degrees: Indian Land and Identity in Natick, Massachusetts, 1650–1790. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Padgett, John F. “Open Elite? Social Mobility, Marriage, and Family in Florence, 1282–1494.” Renaissance Quarterly 63, no. 2 (Summer 2010): 357–411. https://doi.org/10.1086%2F655230.

Palos, Joan Lluís, and Magdalena S. Sánchez. Early Modern Dynastic Marriages and Cultural Transfer (Transculturalisms, 1400–1700). London: Routledge, 2017.

Peirce, Leslie Penn. The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Peyssonnel, Jean-André. Voyages dans les Régences de Tunis et d’Alger, Fragmens d’un voyage dans les régences de Tunis et d’Alger, fait de 1783 à 1786. Paris: Librairie de Gide, Editeur des Annales des Voyages, 1838. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k62092947.

Rheubottom, David. Age, Marriage, and Politics in Fifteenth-Century Ragusa (Oxford Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Ruedy, John. Modern Algeria: The Origins and Development of a Nation Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992.

Saʻīdūnī, Nāṣir al-Dīn. L’Algerois Rural a La Fin de l’époque Ottomane (1791–1830). Beyrouth: Dar al-Gharb al-Islami, 2001.

Shaler, William. Sketches of Algiers, Political, Historical, and Civil: Containing an Account of the Geography, Population, Government, Revenues, Commerce, Agriculture, Arts, Civil Institutions, Tribes, Manners, Languages, and Recent Political History of That Country. Boston: Cummings, Hilliard and company, 1826. http://archive.org/details/sketchesofalgier00shal.

Shaw, Thomas. Travels, or Observations Relating to Several Parts of Barbary and the Levant. Oxford: Printed at the Theatre, 1738.

Shoemaker, Nancy, ed. Negotiators of Change: Historical Perspectives on Native American Women. New York: Routledge, 1995.

Shuval, Tal. “Cezayir-i Garp: Bringing Algeria Back into Ottoman History.” New Perspectives on Turkey 22 (2000): 85–114. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0896634600003289.

Shuval, Tal. “Households in Ottoman Algeria.” Turkish Studies Association Bulletin 24, no. 1 (2000): 41–64.

Shuval, Tal. “The Ottoman Algerian Elite and Its Ideology.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 32, no. 3 (2000): 323–44. https://doi.org/10.1017%2Fs0020743800021127.

Sleeper-Smith, Susan. Indian Women and French Men: Rethinking Cultural Encounter in the Western Great Lakes (Native Americans of the Northeast). Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001.

Spear, Jennifer M. Race, Sex, and Social Order in Early New Orleans. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

Stoler, Ann Laura. Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Stoler, Ann Laura. “Tense and Tender Ties: The Politics of Comparison in North American History and (Post) Colonial Studies.” In Haunted by Empire: Geographies of Intimacy in North American History, edited by Ann Laura Stoler, 23–67. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

Tassy, Laugier de. Histoire du royaume d’Alger. Amsterdam: Chez Henri du Sauzet, 1725.

Taylor, Jean Gelman. The Social World of Batavia: Europeans and Eurasians in Colonial Indonesia (New Perspectives in Southeast Asian Studies). 2nd ed. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009.

Temimi, Abdeljelil. Le Beylik De Constantine Et Hadj `Ahmed Bey (1830–1837). Vol. 1. Tunis: Revue d’histoire maghrébine, 1978.

Tesdahl, Eugene Richard Henry. “Bonds of Money, Bonds of Matrimony? French and Native Intermarriage in 17th and 18th Century Nouvelle France and Senegal.” Master’s Thesis, Miami University, 2003.

Van Kirk, Sylvia. Many Tender Ties: Women in Fur-Trade Society, 1670–1870 Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1983.

Vayssettes, Eugène. Histoire de Constantine Sous La Domination Turque de 1517 à 1837. Bibliothèque d’histoire Du Maghreb. Saint-Denis: Bouchene, 1867.

Weber, André-Paul. Régence d’Alger et Royaume de France: 1500–1800: Trois Siècles de Luttes et d’intérêts Partagés (Histoire et Perspectives Méditerranéennes). Paris: Harmattan, 2014.

Notes

-

Peyssonnel, Voyages, 294. ↩

-

Vayssettes, Histoire de Constantine, 102; Feraud, “Les Harar,” 213–15; Mercier, Histoire de Constantine, 245–46; Benhazer, “La Jeanne d’Arc des Hanencha.” ↩

-

Shuval, “The Ottoman Algerian Elite and Its Ideology”; Shuval, “Cezayir-i Garp”; Shuval, “Households in Ottoman Algeria”; Weber, Régence d’Alger; Merouche, Recherches Sur l’Algérie. Several important exceptions exist, the most important of which are Loualich, La famille à Alger; Missoum, Alger à l’époque Ottomane; Saʻīdūnī, L’Algerois Rural. ↩

-

Some of the most important works include: de Tassy, Histoire; Arvieux, Mémoires; Shaw, Travels; Peyssonnel, Voyages; Vayssettes, Histoire de Constantine; Mercier, Histoire de Constantine; Gaïd, Chronique des beys; Al-ʿAntarī, Farīdah manīsah. ↩

-

Although I put together an initial data set for this study, this project benefitted enormously from the work and insights of three UCLA doctoral candidates—Veronica Dean, Robert Farley, and Suleiman Hodali—without whom this study would not have been possible, particularly within the timeframe in which we completed the data mining and modeling. For another work that uses a similar approach to explore the gaps and silences concerning both free and enslaved African Americans, see Klein, “The Image of Absence.” ↩

-

Stoler, Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power. ↩

-

Molho, “Deception and Marriage Strategy”; Rheubottom, Age, Marriage, and Politics; Padgett, “Open Elite”; Murray, Marriage in Premodern Europe; James, “Marriage by Correspondence”; Palos and Sánchez, Early Modern Dynastic Marriages; Menchi, Marriage in Europe, 1400–1800; Negotiators of Change; Tesdahl, “Bonds?”; McGowan, Dynastic Marriages; Hurtado, Intimate Frontiers; Barr, Peace Came in the Form of a Woman; Van Kirk, Many Tender Ties; O’Brien, Dispossession by Degrees; Sleeper-Smith, Indian Women; DuVal, “Indian Intermarriage”; Spear, Race; Eskridge, “Illinois Culture”; Taylor, The Social World of Batavia. ↩

-

For other examples of historical network analysis see Kane, “All One People”; Morrissey, “Kaskaskia Social Network.” ↩

-

For this type of approach, see Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives. ↩

-

The shortest path between two nodes is the path with the fewest edges and is taken as a measure of distance or closeness between nodes. In a social network graph where nodes represent individuals, when a node is a member of many shortest paths, it demonstrates that person’s “centrality” to the connections that exist between many other individuals. As historians increasingly turn to network analysis to study communities in the past, we are finding that women often tend to rank higher in betweenness centrality scores, so it seems to be a good measure to use when looking for women’s roles and positions within a network. See Maeve Kane, “All One People.” ↩

-

Ouarda Siari-Tengour, “Presentation,” in Histoire de Constantine, edited by Eugène Vayssettes, 15. ↩

-

Mercier, Histoire de Constantine, 284–85; See also de Tassy, Histoire du royaume d’Alger. ↩

-

The following two studies provide evidence that Algerian women were not alone in offering wise council to Ottoman leaders: Kallander, Women, Gender, and the Palace; Peirce, The Imperial Harem. ↩

-

Kallander, Women, Gender, and the Palace; Peirce, The Imperial Harem. ↩

-

We see a similar pattern in the family of Ahmed Bey El Kolli, who married into the Ben Gana and Muqrani families. His Turkish son, Mohammed Chérif, followed his father’s example and married into the Ben Gana family. Mohammed rose to the position of Khalifa, serving in this capacity for several governors. Mohammed’s son, Ahmed, learned these lessons well, and contracted at least seven unions with local women to secure support among the various tribes both in and outside the province of Constantine. Ahmed, in turn, became a provincial governor, the last before the French conquest of the provincial capital in 1837. Temimi, Le Beylik, 60–70; Ruedy, Modern Algeria, 53–57. ↩

Appendices

Author

Ashley Sanders,

Digital Humanities, UCLA, asandersgarcia@ucla.edu,