Slave Streets, Free Streets

Visualizing the Landscape of Early Baltimore

Abstract

If you could immerse yourself in a Google Map of Baltimore as it was two hundred years ago, virtually strolling down the streets and wharves of the early republic city, what would this visualization tell you about the people of the past? Slave Streets. Free Streets: Visualizing the Landscape of Early Baltimore is trying to answer these questions by highlighting the embedded landscape in which approximately 4,300 enslaved and 10,300 free African Americans lived and worked. Using the existing project Visualizing Early Baltimore as a base, Slave Streets, Free Streets allows users to see the way that slavery was enmeshed in the world of early Baltimore (figure 1). It reminds us of the degree to which racial slavery and nascent capitalism spun a web from which people struggled to extricate themselves and their families. It allows us to put faces and names to the largely anonymous ordinary people of the past. Finally, we are also trying to make an argument about the power of visualization as a story-telling medium, to show how mapping can spatially illuminate relationships of power and place.

Slave Streets, Free Streets shows that for all of the ways that Early Baltimore was full of the potential for freedom, it still was a city dominated by racial slavery. Whites and blacks might have lived and worked in close proximity to each other, in the same shipyards and in the same neighborhoods, but they did not have the same opportunities for advancement. The lives of Baltimore’s free blacks, even those who achieved some economic independence, were still shadowed by enslaved kin and the ever-present trade in human beings.1

Baltimore in the years after the War of 1812 was a bustling, thriving port. It teemed with new immigrants from Europe and relocated country folk. Enslaved people worked alongside free blacks and whites in the city’s shipyards and construction sites. Baltimore merchants shipped more flour than their counterparts in any other American city, and the city’s wealth and banking interests helped to make it into a British target during the War of 1812. Baltimoreans also had access to a wide range of imported luxury goods—wines and sherries, olive oil and coffee, silver and textiles (figure 2). But all of Baltimore’s wealth could not ensure adequate sanitation or housing for the thousands of indigent people who filled its back alleys and wharves.

Baltimore was unusual among cities of the time in that its population of free blacks was twice that of the enslaved workers who toiled in the city. This situation was a direct consequence of both Maryland’s location on the literal border between slavery and freedom and the late-eighteenth century shift by many Maryland farmers from tobacco to less labor-intensive cereal crops. As a result of this, Marylanders also adopted the institution of “term slavery,” where an enslaved person and his or her owner would agree that after a certain term of years or at a certain age, the enslaved person would be freed. This agreement was both legally binding and transferable. As a result, many African Americans in Baltimore lived in mixed families, with some members free and some enslaved.2

Slave Streets, Free Streets uses city directories, tax records, newspapers, records of payrolls and licenses, and censuses to put the mosaic pieces of ordinary lives together, giving life to the disfranchised and dispossessed. We use a variety of stories to illuminate two main arguments. The first is the power of visualization as a narrative medium. Our project transforms a geographical map that depicts land features, built structures, roadways, waterways, and ports to a thematic one, illuminating social relationships and information. The cartographic narratives help to make visible relationships of power and class, showing the degree to which social and economic worlds were bounded or fluid. The maps are visualizations, rather than simply illustrations. That is, the argument or story is driven by the visual aspects we highlight and interpret, rather than by only text (figure 3).3

Our other main interpretive argument involves documenting experiences on the border of slavery and freedom. Slavery was inextricably woven through the fabric of society in Baltimore, shaping the lives of blacks and whites, free and enslaved. We spatially demonstrate this experience in several ways. First, in dot-density maps we show that Baltimore’s 1820 population (by ward) was relatively integrated, in vivid contrast with the so-called “black butterfly” configuration of racial, social, and economic segregation revealed in more recent maps of the city (figure 4; cf. figure 5).

To note that the Baltimore of two hundred years ago was less physically segregated than the city is today is not to claim that it was an equitable society. It was not; the peculiar institution was both physically and spatially omnipresent, as a sampling of advertisements in one newspaper, the Baltimore American and Daily Advertiser shows. We looked at the first issue of each month for 1815 – 1820, for a total of 64 issues (some months did not have extant editions). We found and transcribed a total of 442 advertisements that dealt with slavery in some form, and we sorted them into several categories as indicated in the table below.4

| Year (# of issues) | Number of Ads | For Sale | Wanted To Buy | Wanted To Hire | For Hire | Runaway/ Committed to Jail |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1815 (12) | 54 | 20 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 24 |

| 1816 (12) | 94 | 36 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 35 |

| 1817 (10) | 77 | 41 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 24 |

| 1818 (6) | 24 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| 1819 (12) | 107 | 24 (2 overlap with to hire) | 6 | 8 (2 overlap with for sale) | 0 | 69 |

| 1820 (12) | 86 | 17 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 61 |

| TOTAL | 442 | 145 | 35 | 26 | 10 | 246 |

We do not claim that these results are comprehensive; rather they are suggestive. For our purposes, they are most useful for the information about people and places that can be found within the text of the advertisements. Over 90% of our samples mention a location of some sort: the place where a fugitive might have run from or to, the home or business of a seller, or the Baltimore Jail, which housed captured fugitives. This allows users to see that in the absence of a single slave market, the buying, selling, and hiring of enslaved workers was happening all over the city, in newspaper offices and along the wharves, in taverns and merchant shops. With the expansion of cotton cultivation into the Gulf South after 1815, Baltimore became a center of the domestic trade to the Deep South. This transition is visible through the placement of ads seeking large numbers of enslaved workers to sell out of state, as opposed to the more dominant local trade. However, many of the participants in the local buying and selling of enslaved men, women, and children are obscured by the very nature and language of the advertisements. 156 ads for sale or hiring simply asked that interested parties “enquire” at the American Commercial and Daily Advertiser office, which was located at 4 Harrison Street. The Advertiser’s staff presumably was not conducting the transactions, but rather connecting buyers, sellers, and employers, leaving us with no records of these interpersonal transactions.5

Despite these limitations, the advertisements do provide us with a wealth of information about black and white residents of early Baltimore. The sample of 445 transcriptions includes mentions of over 150 African Americans, both (free and enslaved) and over 150 white names. These names allow us to piece together networks of kinship and neighborhood, and complement sources like city directories and tax records. For example, hardware merchant James Biscoe placed the same advertisement in the Advertiser for months in 1819-1820 (figure 6).

100 Dollars Reward

NEGRO HARRY, who calls himself Harry Moshier, left his employer on Saturday evening the 31st ult. and has not been seen or heard of since—Harry is a blacksmith by trade, about 27 years of age, 5 feet 6 or 7 inches high, strong built, broad faced, with rather a sharp chin, dark complexion—has a down sullen look when spoken to—within the last 5 or 6 years he has worked with D. Richards, R. B. Chenowith, J. T. Ford and S. Gill—It is believed that Harry is still in this city, but afraid to return to his work, having been frightened away by false representations of some unknown person. I will give $30 if taken in the city and brought home, $50 if taken in any part of the state without the limits of the city, and $100 if taken out of the state and secured so that I get him again.

JAMES BISCOE 186 ½ Market st.6

This brief document gives us a sense of the world in which Moshier lived and worked as a blacksmith.7 His various owners or employers (Biscoe’s language is unclear) ran their businesses in Old Town at the center of the city, often within a few blocks of each other. Biscoe, who was Moshier’s current owner, owned a hardware store on Market (or Baltimore) street, the city’s main commercial thoroughfare (figure 7). Dutton Richards was a blacksmith with forges on Stillhouse Street, between Duke and Granby. Richard Chenowith was described as a “patent ploughmaker,” with his shop located appropriately on Ploughman Street, which ran between the Falls and Granby street. Chenowith must have run a substantial enterprise, since his 1820 census entry indicated that his household included a total of 13 people engaged in manufacturing, a mix of white, free black, and enslaved men, women, and children. Joseph T. Ford was a cartwright, not to be confused with Joseph P. Ford, a wheelwright; both Fords had addresses on or near Albemarle street. S. Gill was most likely one of two Solomon Gills, both blacksmiths with shops in Old Town.8

But of course there is much we don’t know. Was Moshier hired out to these various shops? Or did he cycle through various owners? The former seems more likely, since all of these white men moved in and out of slaveownership, as was typical for Baltimore artisans. It’s unclear who actually owned Moshier. The 1818 tax records for Baltimore which listed enslaved workers by name and age don’t have a perfect match, although suggestively Richard Chenowith did own a twenty-year-old Harry. He can’t be found directly in the census for 1820 or 1830. Given that he might have been hiding in the city, we can assume he had a network of friends or relatives. But we see him only through Biscoe’s eyes.

A story that reveals more about free black networks and entrepreneurship can be drawn from an advertisement that ran in the American and Commercial Daily Advertiser in the summer of 1815 (seen on August 1, 1815 and September 1, 1815):

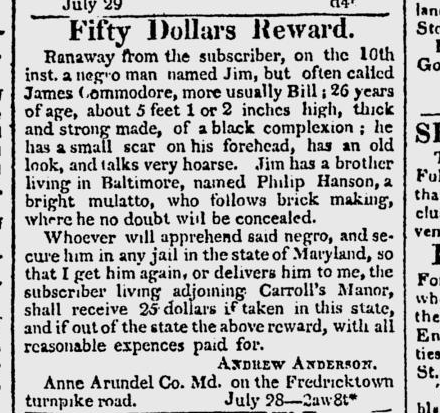

Fifty Dollars Reward.

Ranaway from the subscriber, on the 10th inst. a negro man named Jim, but often called James Commodore, more usually Bill: 26 years of age, about 5 feet 1 or 2 inches high, thick and strong made, of a black complexion: he has a small scar on his forehead, has an old look, and talks very hoarse. Jim has a brother living in Baltimore, named Philip Hanson, a bright mulatto, who follows brick making, where he no doubt will be concealed. Whoever will apprehend said negro, and secure him in any jail in the state of Maryland, so that I get him again, or delivers him to me, the subscriber living adjoning Carroll’s Manor, shall receive 25 dollars if taken in this state and if out of the state the above reward with all reasonable expences paid for.

Andrew Anderson,

Anne Arundel Co. Md. on the Fredricktown turnpike road. July 28.

Baltimore newspapers frequently ran advertisements placed by slave owners from all over Maryland and Virginia. That Andrew Anderson believed Jim ran to Baltimore, in contrast to Harry Moshier running from it, is not surprising; in fact, many of the advertisements placed from other towns had Baltimore as the potential destination, because enslaved people could hide among the large free population.9

It is also not unusual that James Commodore had a free brother, named Philip Hanson, in the city. Hanson was listed as one of just eight black brickmakers in the 1819 Baltimore City Directory (there were over a dozen whites in this occupation). Unusually, Hanson actually owned his property, which was listed in 1818 City Tax records as a lot on the west side of Scott Street, south of Washington Street in Ward 11, valued at $16, with an improved dwelling valued at $40. Only one other black brickmaker owned taxable property in 1818. In 1820, the census taker listed Hanson as the head of an eleven-member household that included four free black men over 25, and seven free black women ranging in age from 14 to over 45.10 With this household size and relative wealth, it is possible to speculate that James Commodore was harbored by his brother. Or perhaps his brother helped Commodore to escape to freedom in the North.

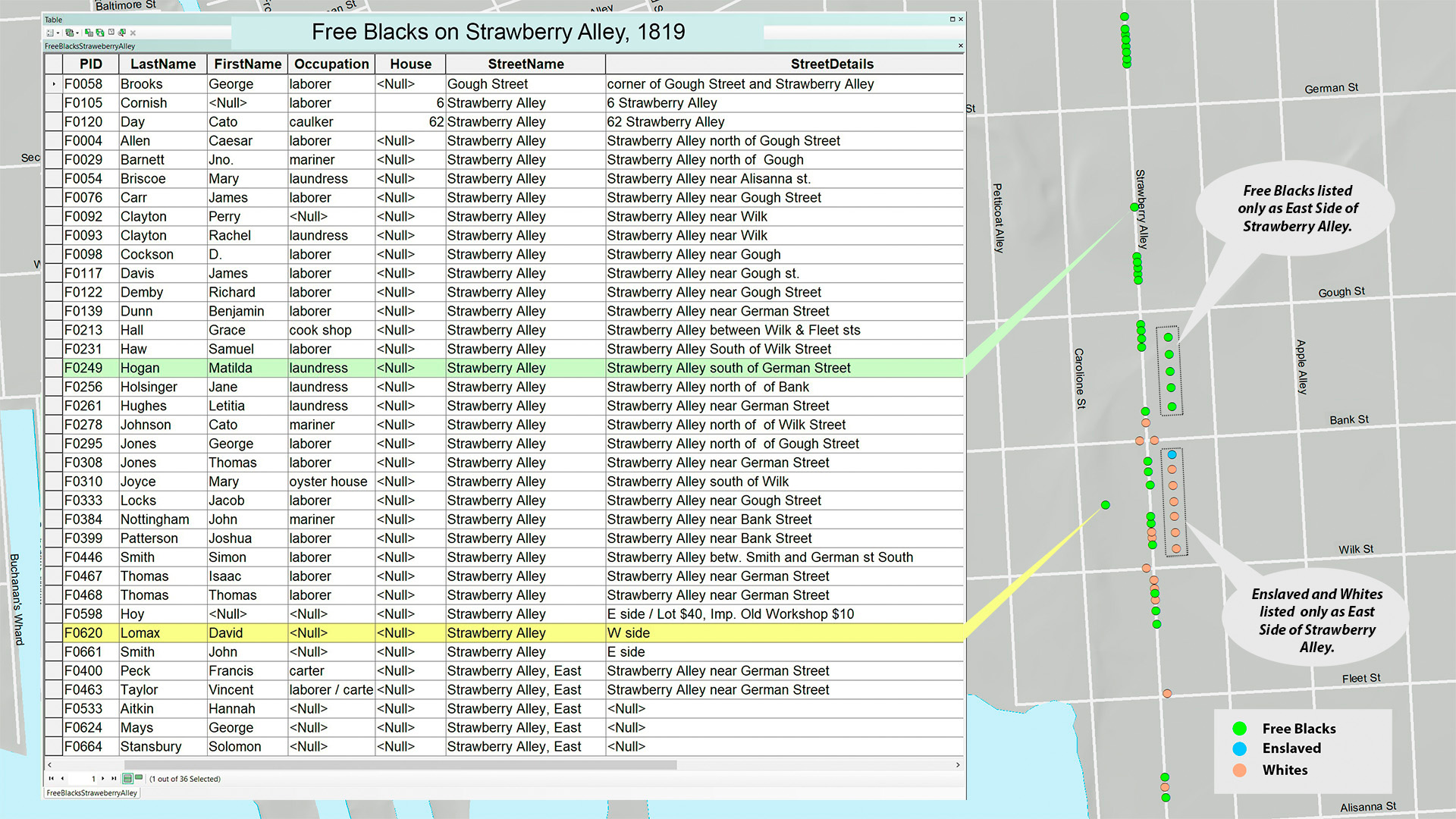

Phillip Hanson is just one example of a free black man who was able to make a living and acquire property in early Baltimore. He lived in Ward 12, in the western part of the city.11 While the population of whites, free blacks, and enslaved workers were relatively equally distributed across Baltimore’s twelve wards, the degree of integration varied within individual wards and neighborhoods. Strawberry Alley, in Fells Point, is a powerful example.

As the home to much of Baltimore’s maritime industry, Fells Point was lined with wharves and shipyards, its streets filled with artisans like carpenters and caulkers, sail makers and riggers. According to city directories and tax records, Strawberry Alley (now known as Dallas Street) was home to 46 free blacks, 21 whites, and 1 enslaved worker. These numbers represent a fraction of Strawberry Alley’s actual residents, since the records only listed heads of households, but we can still draw some conclusions from them. The 46 free blacks included 35 men. Five were described as mariners and two as caulkers. Seven of the men owned their properties; presumably the rest were renters. Of the nine free black women, seven were laundresses, one ran a cook shop, and one operated an oyster house. The white residents seemed to be of a slightly higher economic status, with the 13 men and eight women in artisanal or maritime occupations.12

It’s not surprising that the free black women of Strawberry Alley worked as either laundresses or in food services. These were two common occupations, both of which provided women with a measure of independence and control over their time. Laundress was a job almost exclusively held by black women: the work was hot and exhausting, but done at home, without white supervision, and allowed a woman to watch her children while she worked.13

We can find the names of the household heads who lived on Strawberry Alley much more easily than we can place them on our visualization, however. One of the challenges that we face as we try to map individuals is the imprecision of early nineteenth-century addresses (figure 9). No city in the United States had standardized house numbers before 1828, and Baltimore did not standardize until the 1840s.14 Often we have only north or south of a given block as our only guide; the tax records often included east or west side of the street.

We have placed people in our visualization as accurately as possible. But for the people we cannot place, we are considering putting them on the street itself. We may not know exactly where they lived, but we know that they moved up and down Strawberry Alley, from home to work, to shop and socialize. Early Baltimore’s black residents struggled to make their way in the world, leaving few traces behind. They faced a constant threat from a social, legal, and economic system designed to control them. By recovering and highlighting their lives and work, even to a limited degree, we remind users that their lives mattered.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

The American and Commercial Daily Advertiser (Baltimore), 1815-1820.

Goodson, Noreen J., and Donna Tyler Hollie. Through the Tax Assessor’s Eyes: Enslaved People, Free Blacks and Slaveholders in Early Nineteenth Century Baltimore. Clearfield, 2017.

Jackson, Samuel. The Baltimore Directory, corrected up to June 1819. Baltimore, printed by Richard J. Matchett, 1819.

Keenan, C. (Charles). The Baltimore Directory for 1822 & ’23 : Together with the Eastern and Western Precincts, Never before Included : A Correct Account of Removals, New Firms, and Other Useful Information. Baltimore : Printed by R.J. Matchett, 1822.

Maryland. Baltimore City. 1820 U.S. census, population schedule. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration.

Matchett, Edward. The Baltimore Directory and Register, for the Year 1816 : Containing the Names, Residence and Occupation of the Citizens … Also a Correct List of the Courts … Baltimore [Md.] : Printed & sold at the Wanderer Office, 1816.

Secondary Sources

Arnold, Joseph L. History of Baltimore, 1729–1920, 2015. http://contentdm.ad.umbc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/p16629coll20/id/1044.

Bodenhamer, David J, John Corrigan, and Trevor M Harris. Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives. Indiana University Press, 2015.

Clayton, Ralph. Black Baltimore: 1820–1870. Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 1987.

Clayton, Ralph. Cash for Blood : The Baltimore to New Orleans Domestic Slave Trade. Heritage Books, 2002.

Crenson, Matthew A. Baltimore : A Political History. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017.

Diemer, Andrew. The Politics of Black Citizenship Free African Americans in the Mid-Atlantic Borderland, 1817–1863. University of Georgia Press, 2016.

Evans, May Garretson. “Poe in Amity Street.” Maryland Historical Magazine 36, no. 4 (December 1941): 363–80.

Fields, Barbara Jeanne. Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground : Maryland during the Nineteenth Century. Yale University Press, 1985.

Franklin, John Hope, and Loren Schweninger. Runaway Slaves : Rebels on the Plantation. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Hayward, Mary Ellen. Baltimore’s Alley Houses : Homes for Working People since the 1780s. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

Hunter, Tera. Bound in Wedlock: Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017.

Jones, Martha S. Birthright Citizens : A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America. Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Malka, Adam. The Men of Mobtown: Policing Baltimore in the Age of Slavery and Emancipation. University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Viola Franziska Müller, “Runaway Slaves in Antebellum Baltimore: An Urban Form of Marronage?,” International Review of Social History 65, no. S28 (April 2020): 169–95, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020859020000115.

Phillips, Christopher. Freedom’s Port : The African American Community of Baltimore, 1790–1860. University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Rockman, Seth. Scraping by : Wage Labor, Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

Saunt, Claudio. “Mapping Space, Power, and Social Life.” Social Text, 20 (December 2015): 147–51, https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-3315850

Whitman, T. Stephen. The Price of Freedom : Slavery and Manumission in Baltimore and Early National Maryland. University Press of Kentucky, 1997.

Notes

-

There is a rich literature on the lives of white, free black, and enslaved Baltimoreans. This project draws most heavily on the work of Christopher Phillips, Freedom’s Port : The African American Community of Baltimore, 1790-1860, Blacks in the New World (Urbana, Ill. : University of Illinois Press, 1997); Seth Rockman, Scraping by : Wage Labor, Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009); T. Stephen Whitman, The Price of Freedom : Slavery and Manumission in Baltimore and Early National Maryland (Lexington : University Press of Kentucky, 1997). Other works include Joseph L. Arnold, History of Baltimore, 1729-1920, 2015, http://contentdm.ad.umbc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/p16629coll20/id/1044; Barbara Jeanne Fields, Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground : Maryland during the Nineteenth Century, Yale Historical Publications. Miscellany: 123 (New Haven : Yale University Press, 1985); Martha S. Jones, Birthright Citizens : A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America, Studies in Legal History (Cambridge, United Kingdom ; New York, NY : Cambridge University Press, 2018); Matthew A. Crenson, Baltimore : A Political History (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017); Adam Malka, The Men of Mobtown: Policing Baltimore in the Age of Slavery and Emancipation, Justice, Power, and Politics (University of North Carolina Press, 2018). Ralph Clayton’s work with primary sources is significant as well, but generally focused on the years after 1820. Ralph Clayton, Black Baltimore: 1820-1870 (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, Inc., 1987); Ralph Clayton, Cash for Blood : The Baltimore to New Orleans Domestic Slave Trade (Heritage Books, 2002). ↩

-

Rockman, Scraping By, 112-115; Tera W. Hunter, Bound in Wedlock : Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017). ↩

-

David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan, and Trevor M. Harris, Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015); Claudio Saunt, “Mapping Space, Power, and Social Life,” Social Text XX, (2015), 147–51. ↩

-

Researchers read the first available issue of every month, using images of the American Commercial and Daily Advertiser on Google News. They only transcribed advertisements with a Baltimore connection, so for example an advertisement for a runaway from Virginia that did not mention Baltimore is not included in our database. If an advertisement for a position did not indicate a preference for race, or the race of the person in question it was not included. Many advertisements, especially for runaways, appeared multiple times. The year 1816 also featured one advertisement for a lost African American child, which is not counted in our totals. ↩

-

Baltimore City’s official chattel records, which would have included slave sales, were destroyed many years ago; only random records have survived. See Whitman, The Price of Freedom, 208-209. ↩

-

The ad first appears in our sample on December 1, 1819, and reappears on January 1, 1820, February 1, 1830, and May 1, 1820. It would have likely run every day at least through February. The 31st ult. is probably a reference to October 31, 1819. Had that been the day that Harry Moshier escaped, James Biscoe would not have been able to place an ad in the November 1 edition of the paper. ↩

-

Advertisements for fugitive slaves are valuable and accessible sources of information about African Americans and often their networks. Historians have used them extensively, including in John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger, Runaway Slaves : Rebels on the Plantation. (Oxford University Press, 2000). The new digital project, Freedom on the Move is building a national, searchable database of ads. https://freedomonthemove.org ↩

-

Samuel Jackson, The Baltimore Directory; Noreen J. Goodson and Donna Tyler Hollie, Through the Tax Assessor’s Eyes; 1820 United States Census, Baltimore City, MD. ↩

-

Viola Franziska Müller, “Runaway Slaves in Antebellum Baltimore: An Urban Form of Marronage?,” International Review of Social History 65, no. S28 (April 2020): 169–95, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020859020000115. ↩

-

Hanson appears as Phillip Henson in the 1819 City Directory. Samuel Jackson, The Baltimore Directory, Corrected up to June, 1819, Variation: Early American Imprints.; Second Series ; No. 47067. (Baltimore [Md.]: Printed by Richard J. Matchett, 1819); Noreen J. Goodson and Donna Tyler Hollie, Through the Tax Assessor’s Eyes: Enslaved People, Free Blacks and Slaveholders in Early Nineteenth Century Baltimore (Clearfield, 2017); 1820 United States Census, Baltimore City, MD. ↩

-

Baltimore had three sets of ward boundaries between 1815 and 1820: they changed in 1817 and again in 1818. The Baltimore City Archives has made helpful overlays of ward boundaries on Google Maps: https://msa.maryland.gov/bca/wards/. ↩

-

Information on residents of Strawberry Alley drawn from Mary Ellen Hayward, Baltimore’s Alley Houses ; Noreen J. Goodson and Donna Tyler Hollie, Through the Tax Assessor’s Eyes; Edward Matchett, The Baltimore Directory. ↩

-

The 1816 city directory listed only whites; it had no entries for laundresses. The 1819 city directory included African Americans, and had 113 laundresses listed – all were black. ↩

-

May Garretson Evans, “Poe in Amity Street,” Maryland Historical Magazine 36, no. 4 (December 1941): 363–80; Christopher Thale, “Changing Addresses: Social Conflict, Civic Culture, and the Politics of House Numbering Reform in Milwaukee, 1913–1931,” Journal of Historical Geography 33, no. 1 (January 1, 2007): 125–43, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2006.06.001. ↩

Author

Anne Sarah Rubin,

Department of History, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, arubin@umbc.edu,