Across the Color Line

Using Text Networks to Examine Black and White US Soldiers’ Views on Race and Segregation during World War II

Abstract

In the lead up to the bloody summer of 1943, the US Army was in possession of unambiguous data from “attitude surveys” it had been conducting with service members indicating that racial friction could well spill over from occasional conflict into open rebellion and anarchic violence. Just gathering opinion data related to race had been fraught. The army’s survey program did not even include Black soldiers in the first survey administered the day after Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Their inclusion only followed the application of sustained pressure from Black leaders. Even then, the psychologists and social scientists conducting research for the military wanted assurances that they would be “sufficiently protected against possible repercussions.” The phrasing of questions alighting on racial discrimination could expose them to the charge of planting “leading questions,” while on the other hand, a survey that “omitted all reference to discrimination would hardly be worth making.” They would, therefore, have to make every effort to use “ingenuity in preparing a questionnaire which would elicit information about discrimination in a manner giving the least possible offense to those who might criticize the study,” cautioned the research unit’s acting chief of staff.1 For additional protection, arrangements were also made so that the survey’s authorization would come from outside the research unit, as a directive from the under secretary of war.

The army’s second attitude survey, administered in May and June of 1942, did ask members of the 28th Infantry Division at Camp Livingston, Louisiana; the 2nd Armored Division at Fort Benning, Georgia; and 4th Motorized Division at Camp Gordon, Georgia, for their opinions about integrating post exchanges (PXs), recreation halls, and movies. Yet only White soldiers were queried. The data confirmed what researchers had assumed, namely, that better-educated troops held more liberal views. Still, an internal memo registered surprise at “how many Northerners would deny the Negroes any share in white facilities even if this meant the Negroes would have to go without facilities.”2 Not until the late winter and early spring of 1943, almost a year later, would the army finally address Jim Crow directly and canvas both White and Black troops. Mining extant qualitative data from that survey, Survey 32, this essay contributes to the efforts of scholars striving to understand the transnational struggle for racial equality at the grassroots level and during what has long been considered a seminal moment.3 We do so using scalable digital research methods particularly suited for analyzing this global freedom movement as a true social and political movement which concurrently traversed the individual, micro, and macro institutional levels.

Social scientists and historians know about and have worked with these race surveys.4 Yet, their borrowing is most typically confined to the army’s statistical data, with citations pointing to the reports the Research Branch prepared for army command, which were sometimes condensed in carefully vetted monthly digests for distribution to soldiers; or to the widely known, authoritative four-volume series the branch’s psychologists and social scientists published after the war.5 For the first time, not only is the statistical data available but also a remarkable tranche of associated qualitative datasets—totaling approximately 65,000 pages—which have only recently been transcribed with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities (PW-253766-17 and PW-264049-19). These are free-response commentaries soldiers wrote in response to an open-ended prompt that appeared on the last page of most all army survey questionnaires.

For understanding race, segregation, and racism in the military during World War II and US society more broadly, there is no comparable documentary collection or datasets. We can now assess rank-and-file support for the global freedom movement, as well as opposition to it, thanks to the intensive labor of nearly 7,200 citizen-archivists from around the world. A single survey from February and March 1943 produced over 5,800 handwritten commentaries—2,327 from White enlistees and 3,484 from Black enlistees. Photographed to microfilm in 1947, the larger collection covers a myriad of facets of military service and the war effort; yet the army had a particular interest in preserving commentaries related to race relations. Toward the war’s end in Europe, the Research Branch had studied the effects of integrating Black volunteers into White combat companies, an experiment borne of necessity as the pool of replacements shrank. Its final report, which documented the admirable performance of Black GIs and improved race relations, provided compelling evidence in the accelerated postwar campaign to ban segregation: first in the military in President Truman’s watershed 1948 Executive Order 9981, and then six years later in Brown v. Board of Education.

At the beginning of 1943, Black troops totaled a little over 470,000. With the war widening, their numbers were anticipated to swell.6 In fact, the army these new enlistees would enter had already begun to roll back its universal segregation policy. Two months after the survey that included the 28th Infantry, 2ndArmored, and 4th Motorized divisions, the War Department issued its first directive rescinding Jim Crow by banning the exclusive use of recreational facilities along racial lines in large camps with significant numbers of Black troops. It also left the matter up to local commanders. This and other similar orders were ignored, however, or ways around it were devised, in many quarters. One Black soldier observed, “In this camp and others negro & white soldiers have different PX’s to go to, also they have different sections of army theaters in which to sit. I don’t call that Democracy at all. But at the same time we are suppose [sic] to be fighting for Democracy, and fighting for freedom of speech, freedom from want and etc.” On one post, soldiers from his battalion were “not allowed to walk the camp streets outside the Battalion area because of probable trouble with white soldiers who seemed to pick at us.” He wrote this seven months after the War Department’s first directive, in response to the same open-ended prompt offered to White soldiers. Other Black GIs before him had expressed similar discontent. Surely, however, the conspicuous resistance of White personnel to the War Department’s rescission of strict segregation sharpens the significance of his and other contemporaneous comments. They provide a compelling explanation for the rapid intensification of racial strife that spilled out into the streets of Detroit, Harlem, and Los Angeles, and on a variety of army posts not long after this survey was conducted.7

The Data

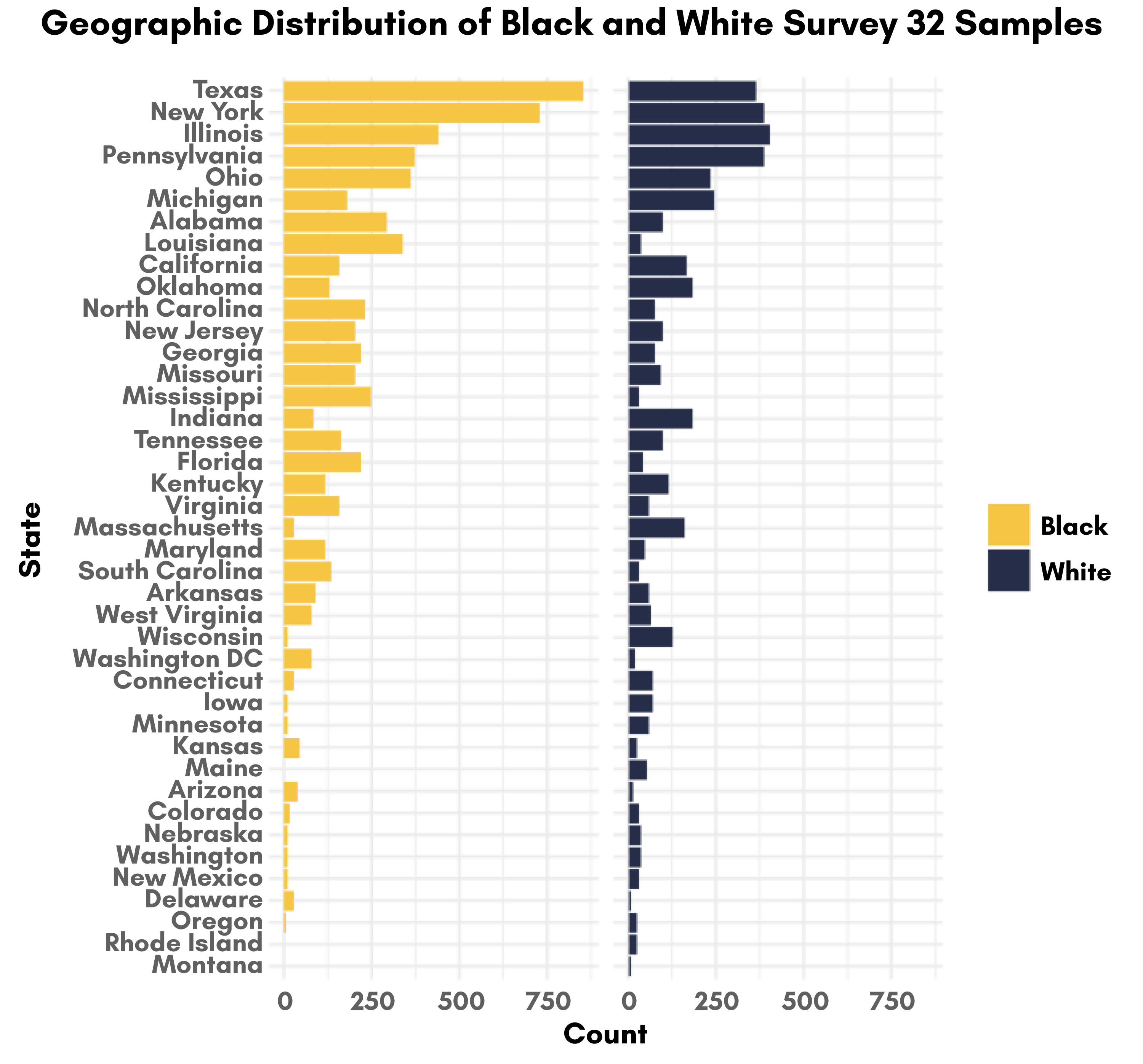

In February and March 1943, the Army Research Branch conducted a crucial study of racial attitudes known as Survey 32. The study is important not only for its timing. It was designed to be comparative and comprehensive. Surveyors selected units located throughout the continental US with the intention of creating a pool of respondents representing a cross-section of the entire army. After arriving at a designated army post, a local survey team used a standardized procedure, calling every nth man from a selected unit until a representative sample size was reached, which was usually one out of every nine or ten service members from the unit. Researchers wanted, for this particular survey, to create regional balance as well. For outfits with more than a hundred members, half of the selected participants were to be Northern men and the other half Southern. Finally, they wanted an inclusive distribution of education levels and of aptitude based on Army General Classification Test (AGCT) scores. The total White sample consisted of 4,793 EM from 71 outfits in 4 Air Force and 6 Ground and Service Force installations. The Black sample was composed of 7,434 EM from 5 Air Force and 13 Ground and Service Force installations. It included a 3,000-person subsample intended as the cross section of all Black EM.

While executing this survey as well as the others it administered, the Army Research Branch typically used self-administered questionnaires. These were considered not only the most reliable instruments but also the easiest to administer for a small research team and support staff tasked with serving the entire organization. Service members with higher AGCT scores filled out a schedule in a “classroom” setting with 40 to 50 service members, while low-scoring personnel or illiterate EM were interviewed by a fellow enlistee of the same race. Survey 32’s White sample was given one questionnaire, S32W, with 64 questions, and the Black sample and subsample another, S32N, with 78 questions. The schedule started with routine demographic questions before asking soldiers for their opinions about the broader war effort, aims of war, postwar plans and social conditions, and international relations. Enlistees were also asked about their personal experience in the army, including their job placement, satisfaction, and aspirations, and about the esprit d’corps.

The survey also queried White and Black enlistees for their opinions about the treatment of Black troops in the army. Black troops were not, however, asked for their opinions about their White comrades, although they were given additional questions regarding race and race relations in the military and about the future of race relations in the United States—e.g., “Do you think that most Negroes are being given a fair chance to do as much as they want to do to help win the war?”—accounting for the slightly longer S32N schedule. Previously, only White soldiers had been asked if they thought it was a “good idea or a poor idea” for White and Black soldiers to have separate PXs and Service Clubs and if White and Black troops should serve in separate or the same outfits. Now in Survey 32, Black troops were given space to air their views. Both samples were also queried to see if these specific facilities were still segregated in their camps, as if to find out from enlistees themselves if post commanders were complying with the secretary’s orders.

Before beginning the survey, soldiers would have been instructed by their “class leader,” a fellow EM stationed at the post, to be entirely candid in their responses. Every soldier was to receive the same reassurance: their response would be strictly anonymous. “The purpose of this survey is for you to express your frank and honest opinion…. No one here in camp sees or reads these questionnaires,” the class leader was to tell them. He was also to reiterate instructions that appeared on the schedule that they were not to write their name or serial number on the schedule. Some soldiers doubted the army’s sincerity, yet the transcribed open-ended responses (known as verbatims) show that the majority of soldiers were glad to have this unusual opportunity to air their views without fear of reprisal.

Methods

The following data visualizations of the White and Black free responses are based on a combination of human and computer intelligence. Within the Black EM sample, 47 percent wrote at least something in response to the open-ended prompt on the last page of their schedule, as did 48 percent of White soldiers. We began our analysis by reading and classifying several thousand verbatims to help identify recurring rhetorical characteristics and salient themes across the datasets. We then employed computational text analysis to convert these qualitative free responses into text correlation networks. Building on the Brubaker et al.’s framework, we use these text networks as a methodology to conceptualize the racialized cognitive schemas of Black and White soldiers.8

We started the conversion process by applying tidytext, a package developed for text mining and data visualization in the R open-source software environment.9 After removing punctuation and metatags that had been added by transcribers, and reducing words to their roots by stemming, lemmatizing, and eliminating numbers, we used tidytext to count the frequency of terms within the text and then construct co-occurrence networks. A co-occurrence refers to two words appearing within the same text response. After obtaining the raw counts of co-occurrences between all words, we normalized these relationships based on the pairwise phi correlation coefficient and then reduced the dataset to words that were mentioned more than 20 times and had a correlation of greater than 0.1. These relationships serve as the backbone for our text networks.

In these networks, nodes represent words mentioned in the soldiers’ free-response data. Edges correspond to the pairwise phi correlation coefficients of how often words are mentioned together in the same response. Scaled between 0 and 1, edge weights depict correlations between words, with stronger correlations having thicker edges. The color of a node aligns with the results of a Louvain community detection method that clusters groups of words together into network communities based on their relatedness such that similarly colored nodes share more densely determined connections.10 The size of a node corresponds to the number of connections a word has to others in the graph (i.e., the degree centrality), with larger nodes sharing more connections to other words within the network community. After this reconstruction was complete, we used the open-source visualization platform Gephi to create the following customized network figures.11

Results

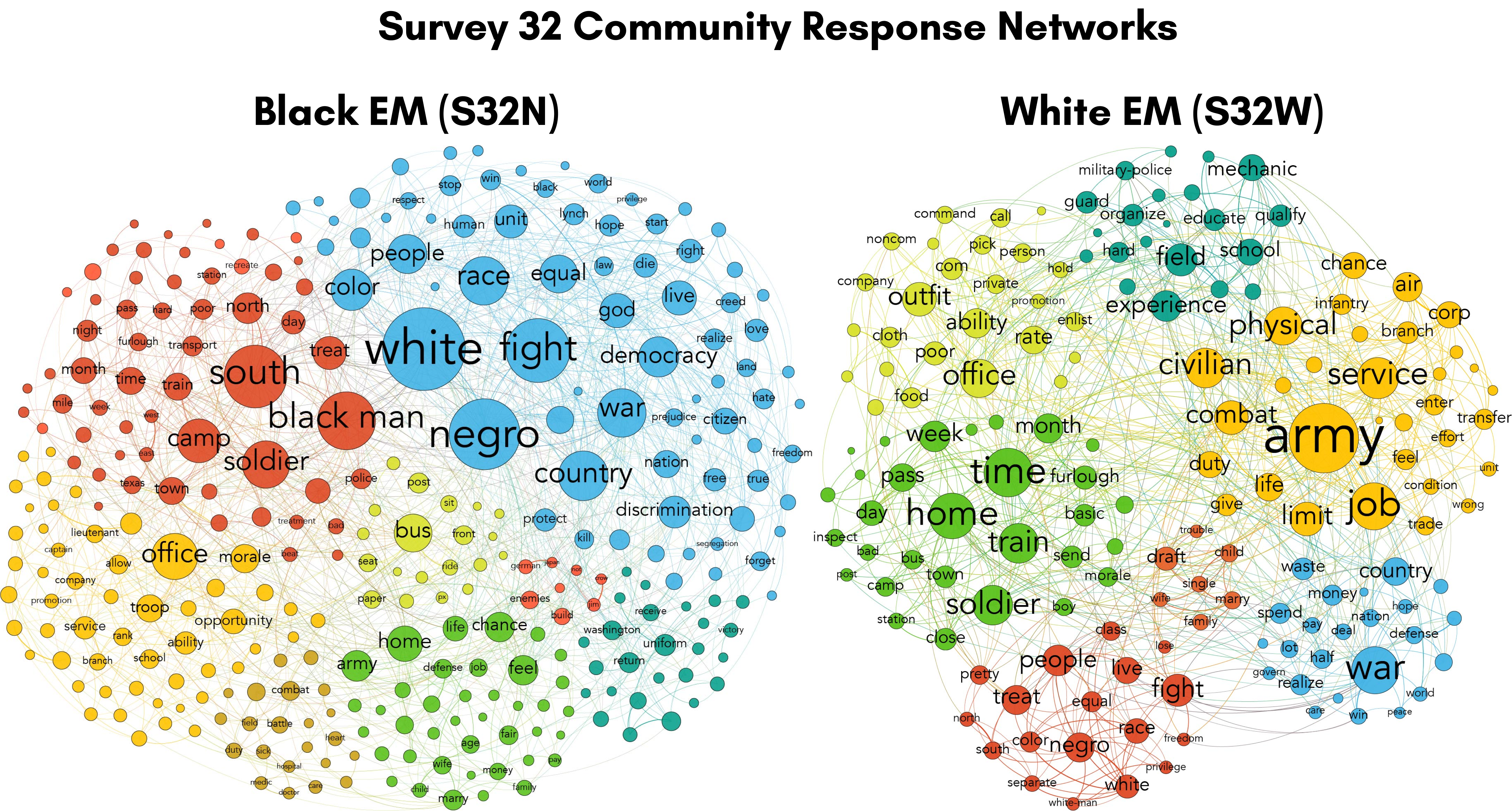

We initially attempted to compare and contrast responses from Survey 32’s White and Black populations by creating parallel community response network graphs for the two populations using matching colors. (Again, colors correspond to the groupings of words with more densely determined connections, while the size of words shows how connected each is to others within the same network.) This parallel colorization did not work particularly well, however, as the community networks derived from the soldiers’ verbatims were simply too dissimilar. We might have expected as much, based on our reading of the verbatims. Still, as seen in figure 4, the data visualizations brought into sharp relief just how divergent the experiences of the war and of military service were for Black and White enlistees in their own words.

First, notice the White community response network shown in figure 4. Drawing on Cheryl I. Harris’s seminal essay,12 the sociologist Victor Ray argues that organizations like the military are predicated on cognitive schemas that connect organizational rules to the distribution of social as well as material resources.13 These racialized schemas, reinforced through segregation and often obfuscated through racially neutral bureaucratic rules, block equal access not only to everyday resources, but also pathways to job promotion that solidify the long-term accrual of financial and social capital for Black soldiers. Whiteness, on the other hand, can be leveraged as a credential to gain status within the hierarchy of the already predominantly White military.14

The network visualizations support Ray’s insights. The word army represents by far the largest node among the White community networks. The organization and its inner workings are at the forefront of White soldiers’ thoughts and concerns, particularly the ways in which they might secure or elevate their status within it. This is conveyed by the words duty, job, and service in the mustard yellow community; train[ing] and soldier in the green community; ability, rat[ing], and officer in chartreuse; and experience, school, qualify, educate, and organize in teal. All relate in one way or another to organizational status. Notice, too, the concern seen in the blue network for misallocation of resources, illustrative of the integral relationship of Whiteness, status, and resource distribution. The table in figure 5 offers a more detailed look at the word communities found in figure 4.

Communities in the Response Networks, Ordered by Size

| Black Response Network | White Response Network | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Blue | Race and struggle: white, negro, color, fight, equal, discrimination, prejudice, segregation, hate, country, war, democracy, citizen | Yellow | Profession and combat: army, service, duty, give, life, limit, physical, combat, transfer, effort, infantry |

| Red | Race and place: black man, bad, treat, soldier, camp, station, police, transport, recreate, night, north, south, east, west | Green | Training and time off: train, soldier, basic, home, time, week, day, furlough |

| Yellow | Training and promotion: office[r], opportunity, ability, rank, troop, school, promotion, captain | Chartreuse | Promotion and camp conditions: office[r], ability, rate, poor, promotion, private, com, noncom |

| Bronze | Health and combat: combat, battle, field duty, sick, hospital, doctor, medic, care | Teal | On-camp training: field, experience, school, educate, mechanic, guard, military-police |

| Green | Military and personal life: army, home, life, chance, job, age, wife, marry, child, family, pay | Red | Race and place: treat, equal, fight, negro, white, white man, race, color, north, south, privilege |

| Chartreuse | Localized racial tensions: bus, ride, sit, front, seat, post, px (post exchange) | Blue | Resources and aims of war: war, country, nation, waste, spend, money, win, peace, hope |

| Orange | Enemies and white supremacy: enemies, german, japan, jim, crow | Orange | Personal life: single, family, wife, child, marry |

| Teal | Recognition of service: uniform, washington, return, receive, victory |

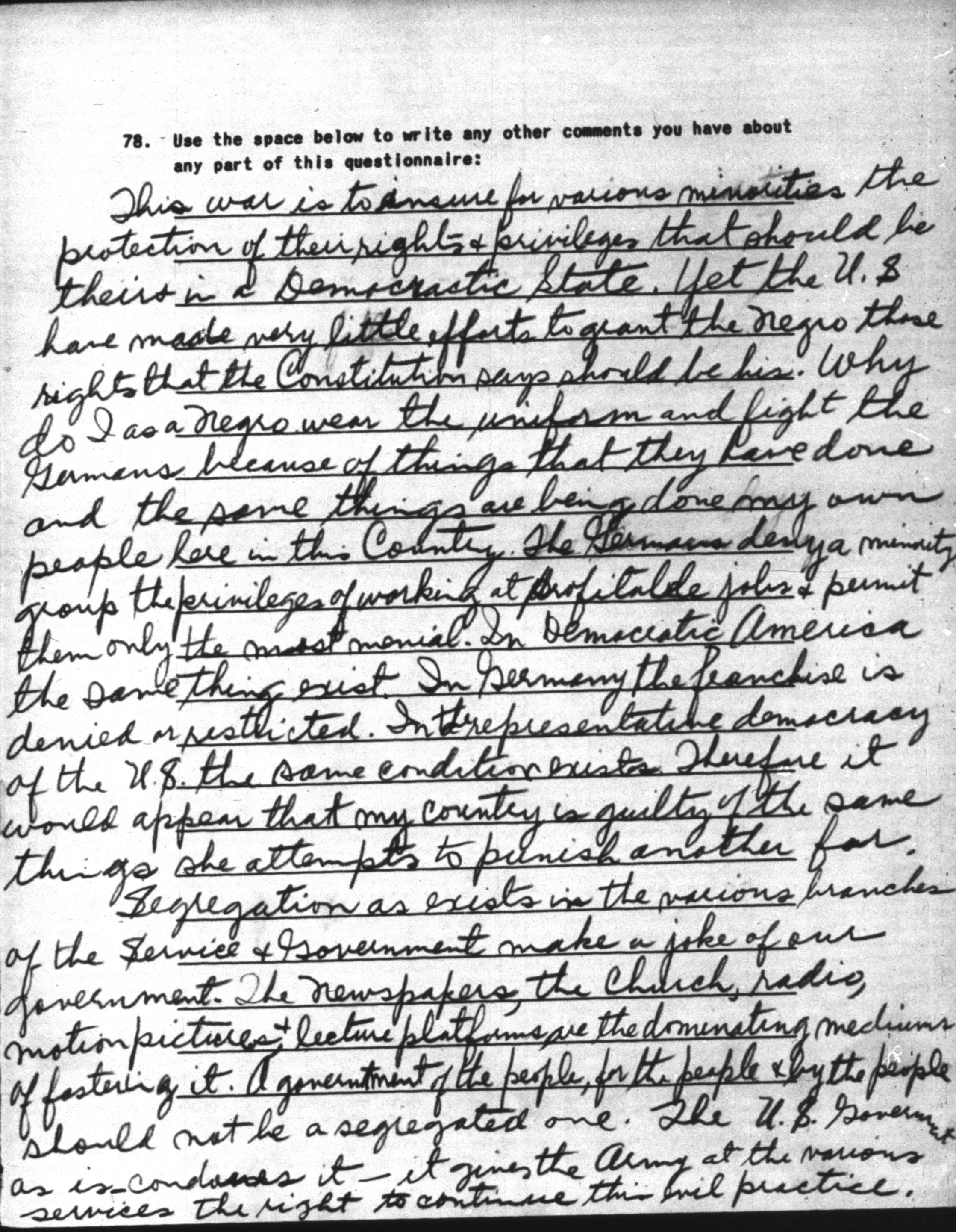

Compare the community response network from White enlistees in figure 4

with the one based on the Black soldiers’ free responses in the same

figure. The prominent co-occurrence of white with black man and

white with negro intersecting the most extensive

communities—colored blue and red—recall the sociologist W.E.B. Du

Bois’s concept of “double consciousness,” the Black American’s

ineluctable habit of mind of “always looking at one’s self through the

eyes of others.” Du Bois elaborated, “One ever feels his twoness—an

American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings;

two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps

it from being torn asunder.”15 While the term white is only the

third most frequently occurring term in the Black response network

following negro and america as seen in figure 6, it emerges as the

most prominent co-occurrence. Indeed, observe its significant

relatedness to black man and negro as well as its proximity to other

frequently co-occurring words, like color, treat, people, race,

fight, democracy, god, country, war, and equal(ity). The

visualization thus brings into relief the distressed double

consciousness that so many of these citizen-soldiers serving in a

manifestly undemocratic, unequal army expressed in their handwritten

remarks—an example of which is shown in figure 7.

Top Word Frequencies by Racial Group

| Black Soldiers | Count | White Soldiers | Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| negro | 1371 | america | 715 |

| america | 1317 | army | 647 |

| white | 1061 | soldier | 406 |

| army | 1060 | war | 316 |

| war | 934 | time | 249 |

| soldier | 926 | office | 235 |

| south | 689 | service | 197 |

| fight | 652 | job | 196 |

| black-man | 578 | train | 178 |

| office | 528 | outfit | 173 |

| treat | 515 | negro | 166 |

| color | 470 | home | 158 |

| chance | 463 | life | 140 |

| people | 451 | chance | 136 |

| camp | 467 | camp | 132 |

| time | 405 | feel | 130 |

| home | 374 | fight | 128 |

| country | 348 | country | 106 |

| feel | 320 | people | 104 |

![Image of a scanned document. The document contains a handwritten response to S32N survey question 78 which reads "Use the space provided to write any other comments you have about any part of this questionnaire." The response says: "After these questionaires are read what action will be taken to better our army conditions? In regards to seperate PX's [Post Exchanges] & service clubs, a white soldier can get away with entering our P.X.s [Post Exchanges] and service clubs & event have intercourse with our women. Enter one of theirs or have an intercours with a white woman & immediatly their theres is cry of blood retaliation, even in the theaters. They go so far as to have separate windows to buy tickets & a restricted area to sit in. Yet we wear the same uniform, draw the same pay & is fighting for the same cause. I ask if you cut us do we not bleed as the do, do we too not shed tears, sweat & die as the do for the same cause? Then why are we treated as an inferior race, our inteligence & education ranks on the same level as any white mans, sometimes even higher. United we stand Devided we fall, & we are a divided country. racial discrimination & yet dark hands buy bonds & mold bullets the black and white alike use. let their be a change, light in this dark nation. lets unite as one against our common enymy [enemy] the NATZIS.”](https://crdh.rrchnm.org/assets/img/v06/gitre/figure7.jpg)

White as well as Black enlistees had been primed by survey questions to reflect on race in the armed forces and the possibility of integrating certain facilities. Yet in their free responses, White soldiers mentioned their counterparts’ race less frequently, and their own race or ethnicity even less frequently. Race consciousness is not absent entirely from their remarks. Still, the marked asymmetry captured in figure 4 recalls Charles Mills’s observation about the inverted epistemology of racism, the “not knowing,” or epistemology of “white ignorance,” by which White structural supremacy is maintained irrespective of whether members of a society or, in this case, the organization are, as he describes them, “racist cognizers.”16 Within a hierarchical organization that channeled resources unequally, White soldiers could concentrate on ratings, rank, job training and promotion, education, and other status-enhancing pursuits, as well as family and home life. Meanwhile, what occupied the thoughts of a majority of Black EM was the inequitable distribution and policing of these resources, seen in the many references in their commentaries to transportation (bus, seat, ride) and police, to PXs, shown in the chartreuse community, and to training and promotion, in the yellow.

In light of the challenges of analyzing verbatims comparatively across networks relying on colorization, we combined Survey 32 textual data sets, or edgelists, into a single multi-layered network. This allowed us to correlate edges between nodes based on the racial identification of the respondent. In figure 8, orange ties represent words written by White soldiers, and blue ties by Black soldiers. The blue edges pull toward the left-hand side of the graph and orange edges to the right. Both Black and White EM wrote about their camps, the war, the job, and being given a chance, as one can see in the middle of the graph. Yet the graph is strikingly bifurcated. The two-ness of the Black citizen-soldier is brought to the fore by the dominance of white and negro in the wash of blue edges, as we saw in figure 4. Working counterclockwise from the bottom left, see treat, black-man, color, south, democracy, equal, race, fight, country, and war. Now observe on the opposite side of the graph the overriding concern of White EM—the army—not only how they might pass their time in it (referenced by time, spend, day, week, night), but also how they might elevate their status, principally by becoming a non-commissioned officer.

The graph’s bifurcation corroborated our initial analysis, but the volume of nodes and edges undercut legibility, so we constructed a third set of graphics, shown in figure 9. We applied Louvain community detection to the full network to create visualizations that disentangled the previous graph while retaining its essential structure. To maintain visual integrity, we also retained the blue and orange colorization of edges. Finally, we filtered the communities to those that best illustrate racial bifurcation. The large blue community from S32N in figure 10, centered on race and equality, is almost entirely devoid of orange edges. This absence more starkly captures White soldiers’ racial ignorance, how they distance themselves from the racial oppression of Blacks in the military in addition to their own privileged status within that structure. As seen in the green community in figure 9’s S32W graph, White enlistees devoted more of their attention to furloughs and passes and to spending time at home and with family; and again, they do so because they can.

Black soldiers wrote about furloughs and home, too, just as they also wrote about the inner workings of the organization—about opportunity, ratings, qualifying, and ability. But there is a qualitative difference to their written comments as figure 7 shows. The chartreuse community co-occurrences related differently to the inner workings of the army appear in the two graphs. In the S32W graph in figure 9, derived from the White EM corpus, the edges are more complex and plentiful and indicate greater integration; in comparison, the chartreuse edges in the Black EM subgraph are not nearly as dense. We saw in our close reading of S32N verbatims a great desire among Black soldiers that they be led by officers of their own race. Many wanted to become noncommissioned officers themselves and pled with the army that officers be selected not according to race but ability (see ability to the bottom right of officer in figure 9’s S32N graph). As the White GIs understood that officers were gatekeepers to the military’s social and material resources, so, too, did Black enlistees. The more-attenuated chartreuse community of the Black EM network in figure 9 speaks to their cognizance of this gatekeeping role, and it is suggestive of the effects of being denied access, as Black soldiers were.

Conclusion

In this paper, we explored the discursive tendencies and characteristics of Black and White soldiers and their perspectives on segregation in the military during World War II. To do this, we leveraged aspects of computational text analysis to convert textual data from more than five thousand uncensored open-ended survey responses into text correlation networks. The visualizations from these networks illuminate in vivid detail the manifold micro effects of Jim Crow in the everyday lives and thoughts of White and Black soldiers serving in the same military organization.

These open-ended responses from soldiers complement other primary-source collections related to the war, Jim Crow, and the civil rights movement while also providing new and challenging insights. As such, our analysis engages in what the digital historian Kim Gallon has called the “technology of recovery,” the exigent aim of which is to use digital platforms and tools to disrupt prevailing, exclusionary characterizations of “the humanities” for recognition of marginalized peoples, and their “full humanity.”17 The Black press has long been recognized as a vital primary source base for bringing forth the full humanity of Black Americans, especially during World War II by publishing the personal accounts of individual service members and documenting the prevalence of violence and prejudice against Black citizen-soldiers and war workers. The large-scale digitization of historical newspapers such as the Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier has been an unqualified boon for Gallon and other Black studies scholars working inside and outside the digital humanities.18

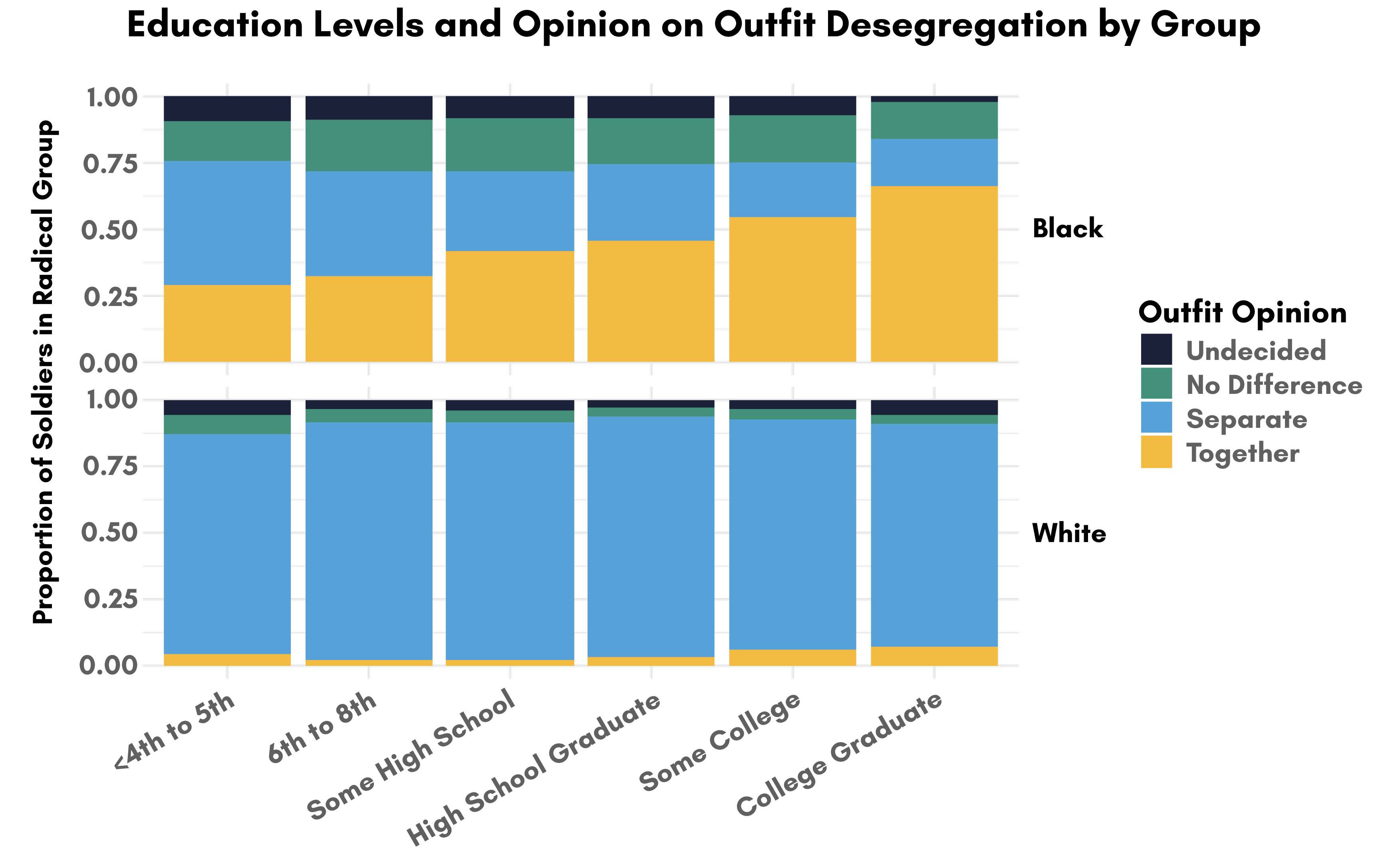

The unstructured survey responses from Black and White soldiers in Survey 32 complement these newspaper accounts of anti-Black racism. A number of Black GIs’ survey questionnaires voiced support for the “Double Victory” campaign championed by WWII Black editors and the NAACP, which called for victory against fascism abroad as well as White supremacy at home. The survey responses the army collected demonstrate just how extensively the campaign was adopted among the rank-and-file. Yet, the transcribed verbatims illuminate a far broader and at points irreconcilable range of opinions. Black newspaper editors and the NAACP’s leadership demanded full integration up and down the forces. Nevertheless, many Black troops expressed support for separate facilities and units, as figure 3 shows, most notably enlisted personnel with lower educational levels. Soldiers on the other side of the color line also confounded the political aspirations and views of Black leaders and editors. When the NAACP’s executive secretary Walter White received survey results that showed how firmly opposed a majority of White soldiers were to integrated facilities, he questioned the survey’s accuracy.

The visualizations created from our text correlation network not only benefited from our close reading of these multivocal, uncensored primary sources; they also sent us back to our sources to open new lines of inquiry. The prevalence of references to organizational resources among White respondents in S32W in contrast to S32N was especially intriguing. By comparing open-ended responses with archived institutional records, we discovered that the army did try to desegregate particular facilities on army posts to begin to rectify the unequal distribution of resources. But White soldiers and officers often resisted, exacerbating racial tensions and provoking more physical violence. Handwritten verbatims from a survey administered in August 1944, “Survey 144: Post-war Plans of Negro Troops,” reflect this growing animosity. Quite a few Black soldiers who took the survey explicitly attributed their anger and frustration to White officers and soldiers blocking their access to these resources, among them, post exchanges, transportation facilities, and recreational facilities.

In the future, we would like to extend our computational techniques to this later survey to see what additional insights we can glean. We believe that these newly transcribed datasets document, in coruscating detail, rapid shifts in racial attitudes over the course of a few, crucial years, and can therefore illuminate a shift that accelerated the postwar civil rights movement and sparked new waves of White “massive resistance.”

Bibliography

Alpers, Benjamin L. “This is the Army: Imagining a Democratic Military in World War II.” Journal of American History 85, no. 1 (June 1998): 129–63. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2568436.

Aragon, Margarita. “‘A General Separation of Colored and White’: The WWII Riots, Military Segregation, and Racism(s) beyond the White/Nonwhite Binary.” Sociology of Race & Ethnicity 1, no. 4 (2015): 503–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649215579282.

Basevich, Elvira. “W.E.B. Du Bois’s Critique of American Democracy during the Jim Crow Era: On the Limitations of Rawls and Honneth.” Journal of Political Philosophy 27, no. 3 (2019): 318–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopp.12189.

Bastian, Mathieu, Sebastien Heymann, and Mathieu Jacomy. “Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks.” In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 3, no. 1 (2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1341.1520.

Blondel, Vincent D., Jean-Loup Guillaume, Renaud Lambiotte, and Etienne Lefebvre. “Fast Unfolding of Communities in Large Networks.” Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 2008, no. 10 (2008): P10008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/p10008.

Bolzenius, Sandra M. Glory in Their Spirit: How Four Black Women Took on the Army during World War II. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2018.

Bristol, Douglas Walter, Jr. “Terror, Anger, and Patriotism: Understanding the Resistance of Black Soldiers during World War II.” In Integrating the US Military: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation since World War II, edited by Douglas Walter Bristol Jr. and Heather Marie Stur, 10–35. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017.

Brubaker, Rogers, Mara Loveman, and Peter Stamatov. “Ethnicity as Cognition.” Theory and Society 33, no. 1 (2004): 31–64. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:RYSO.0000021405.18890.63.

Delmont, Matthew F. Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad. New York: Viking Press, 2022.

Du Bois, W. E. B. The Souls of Black Folk. Rev. ed. Edited by Brent Hayes Edwards. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Dwyer, Owen J., and John Paul Jones III. “White Socio-spatial Epistemology.” Social & Cultural Geography 1, no. 2 (2000): 209–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360020010211.

Fruchterman, Thomas M., and Edward M. Reingold. “Graph Drawing by Force‐directed Placement.” Software: Practice and Experience 21, no. 11 (1991): 1129–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/spe.4380211102.

Gallon, Kimberly. “Making a Case for the Black Digital Humanities.” In Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016, edited by Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.5749/9781452963761.

Gallon, Kimberly. Pleasure in the News: African American Readership and Sexuality in the Black Press. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.5406/j.ctv1220rp4.

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Guglielmo, Thomas A. Divisions: A History of Racism and Resistance in America’s World War II Military. New York: Oxford, 2021.

Harris, Cheryl I. “Whiteness as Property.” Harvard Law Review 106, no. 8 (1993): 1707–91.

Hovland, Carl I., Arthur A. Lumsdaine, and Fred D. Sheffield. Experiments on Mass Communication. Studies in Social Psychology in World War II. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1949.

Jacomy, Mathieu, Tommaso Venturini, Sebastien Heymann, and Mathieu Bastian. “ForceAtlas2, a Continuous Graph Layout Algorithm for Handy Network Visualization Designed for the Gephi Software.” PloS ONE 9, no. 6 (2014): e98679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098679.

Jefferson, Robert F. Fighting for Hope: African American Troops of the 93rd Infantry Division in World War II and Postwar America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

Knauer, Christine. Let Us Fight as Free Men: Black Soldiers and Civil Rights. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

Kruse, Kevin M. and Stephen Tuck, eds. Fog of War: The Second World War and the Civil Rights Movement. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Kryder, Daniel. “Race Policy, Race Violence, and Race Reform in the U.S. Army during World War II.” Studies in American Political Development 10, no. 1 (Spring 1996): 130–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898588X00001449.

Lee, Ulysses. The Employment of Negro Troops. U.S. Army in World War II. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Military History, United States Army, 1966.

Lentz-Smith, Adriane. Freedom Struggles: African Americans and World War I. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009.

MacGregor, Morris J. Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940–1965. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 1981. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.31210003246814.

McGuire, Danielle L. At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape and Resistance—a New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power. New York: Vintage, 2010.

McGuire, Phillip, ed. Taps for a Jim Crow Army: Letters from Black Soldiers in World War II. University Press of Kentucky, 2021.

McMillan Cottom, Tressie. Thick: And Other Essays. New York: The New Press, 2019.

Mills, Charles. “White Ignorance.” In Race and Epistemologies of Ignorance, edited by Shannon Sullivan and Nancy Tuana, 11–38. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2007.

Mueller, Jennifer C. “Racial Ideology or Racial Ignorance? An Alternative Theory of Racial Cognition.” Sociological Theory 38, no. 2 (2020): 142–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275120926197.

Parker, Christopher S. Fighting for Democracy: Black Veterans and the Struggle against White Supremacy in the Postwar South. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Phillips, Kimberley L. War! What Is It Good For? Black Freedom Struggles and the U.S. Military from World War II to Iraq. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Polk, Khary Oronde. Contagions of Empire: Scientific Racism, Sexuality, and Black Military Workers Abroad, 1898–1948. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020.

Ray, Victor. “A Theory of Racialized Organizations.” American Sociological Review 84, no. 1 (2019): 26–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122418822335.

Ray, Victor. “Critical Diversity in the US Military: From Diversity to Racialized Organizations.” In Challenging the Status Quo: Diversity, Democracy, and Equality in the 21st Century, edited by David G. Embrick, Sharon M. Collins, and Michelle S. Dodson, 287–300. New York: Brill, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004291225.

Segal, David R. and Peter G. Nordlie. “Racial Inequality in Army Promotions.” Journal of Political & Military Sociology 7, no. 1 (Spring 1979): 135–42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45293839.

Silge, Julia, and David Robinson. “tidytext: Text Mining and Analysis Using Tidy Data Principles in R.” Journal of Open Source Software 1, no. 3 (2016): 37. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00037.

Stouffer, Samuel A., Edward A. Suchman, Leland C. DeVinney, Shirley A. Star, and Robin M. Williams Jr. Adjustment During Army Life. Studies in Social Psychology in World War II. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1949.

Stouffer, Samuel A., Arthur A. Lumsdaine, Marion Harper Lumsdaine, Robin M. Williams Jr., M. Brewster Smith, Irving L. Janis, Shirley A. Star, and Leonard S. Cottrell Jr. Combat and Its Aftermath. Studies in Social Psychology in World War II. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1949.

Stouffer, Samuel A., Louis Guttman, Edward A. Suchman, Paul F. Lazarsfeld, Shirley A. Star, and John A. Clausen. Measurement and Prediction. Studies in Social Psychology in World War II. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950.

Williams, Chad L. Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Notes

This publication uses data generated via the Zooniverse.org platform, development of which is funded by generous support, including a Global Impact Award from Google, and by a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editorial staff at Current Research in Digital History for their insightful and generous comments and feedback, which considerably improved the final manuscript.

-

John B. Stanley, Memorandum to the Chief of the Special Services Branch, Subject: Special Planning Survey, 1 April 1942, SP III, Panel Survey, box 3, Reports and Analysis of Attitude Research Surveys, Planning Surveys 2-3, entry A1 92, RG 330, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), College Park, MD. ↩

-

S.A. Stouffer, Memorandum to Major Stanley, Subject: Attitude of White Soldiers Toward Use of Facilities by Negroes, 9 June 1942, Planning Survey II (3 Ground Forces Camps) May-June 1942, box 3, entry A1 92, RG 330, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), College Park, MD. ↩

-

Bolzenius, Glory in Their Spirit; Bristol Jr., “Terror, Anger, and Patriotism,” 10–35; Delmont, Half American; Guglielmo, Divisions; Jefferson, Fighting for Hope; Knauer, Let Us Fight; Kruse and Tuck, eds. Fog of War; Lentz-Smith, Freedom Struggles; McGuire, Dark End; McGuire, ed. Taps; Polk, Contagions of Empire; Williams, Torchbearers of Democracy. ↩

-

Alpers, “This is the Army”; Bristol Jr., “Terror, Anger, and Patriotism,” 10–35; Guglielmo, Divisions; Kryder, “Race Policy,” 130–67; Lee, Employment of Negro Troops; MacGregor, Integration; Phillips, War!; Segal and Nordlie, “Army Promotions,” 135–42. ↩

-

Stouffer et al., Adjustment During Army Life; Stouffer et al., Combat and Its Aftermath; Hovland et al., Experiments on Mass Communication; Stouffer et al., Measurement and Prediction. ↩

-

Lee, Employment of Negro Troops, ch. 14. ↩

-

Aragon, “General Separation,” 503–16. ↩

-

Brubaker, Loveman, and Stamatov, “Ethnicity as Cognition,” 31–64. ↩

-

Silge and Robinson, “tidytext,” 37. ↩

-

Blondel et al., “Fast Unfolding,” P10008. ↩

-

Bastian et al., “Gephi.” ↩

-

Harris, “Whiteness as Property,” 1707–91. ↩

-

Ray, “Racialized Organizations,” 26–53. ↩

-

Ray, “Racialized Organizations”; Ray, “Critical Diversity,” 287–300. ↩

-

Du Bois, Souls of Black Folk, 8; Basevich, “W.E.B. Du Bois’s Critique,” 318–40; Gilroy, Black Atlantic; McMillan Cottom, Thick, 99–126. ↩

-

Mills, “White Ignorance,” 11–38. ↩

-

Gallon, “Black Digital Humanities.” ↩

-

Gallon, Pleasure in the News; Delmont, Half American. ↩

Authors

Edward J.K. Gitre,

Department of History and Center for Human-Computer Interaction, Virginia Tech, egitre@vt.edu,