The Republican Party’s Other Right: A Computational History of the Old Right’s Noninterventionism and their Decline within the GOP, 1934-1992

Abstract

Veteran Representative H.R. Gross felt confident in the spring of 1961, having just secured a seventh term representing the Hawkeye state’s 3rd Congressional district through a decisive victory in the 1960 general election. Known for his reputation as a budget hawk, Gross was also an ardent critic of U.S. government intervention in world affairs. From his earliest days in Congress, Gross had been an ardent detractor of foreign aid and a vocal opponent of the Korean War. An equal opportunity curmudgeon, Gross opposed U.S. support for Tito’s communist regime in Yugoslavia and Franco’s falangist regime in Spain. He similarly opposed aid to the ailing European empires, especially Great Britain, against whom he held a grudge formed from his days on the Western Front during World War I.

Speaking at the Manion Forum, a prominent conservative radio program in March 1961, Gross assailed the now adolescent Cold War order and pointed to his campaign victory as evidence that significant dissent remained on the political right. He criticized U.S. Cold War policy, noting that “[w]e have given economic and military aid to dictators who then used this aid to suppress their own people in the name of anti-communism” and argued that such efforts failed to fashion “a world that is peaceful, prosperous, or free.” 1

Gross was the longest-serving member of a political cohort retroactively known as the Old Right. On foreign policy issues, the Old Right held on to an idealized vision of a restrained America. Based mainly within the rural Midwest, the Old Right was an assortment of strident anti-New Dealers, nativists, trade protectionists, and noninterventionists. They opposed everything big: big government, big labor, big business, and big banks. They embraced romantic notions of American exceptionalism and scorned Europe as a land of depravity. These core beliefs translated into foreign policy positions which opposed entangling alliances, government-directed foreign investment, and large standing armies. While the Old Right included several lapsed liberals and pre-New Deal Western progressives, their opposition to the emerging Cold War order drew much of its impetus from opposition to the New Deal, memories of World War I and opposition to Wilsonianism.2 Therefore, the noninterventionist right saw the emerging Cold War order as a ploy to secure through permanent militarism, Keynesian economics at home, corrosive multilateral security arrangements with Europe, and wasteful and counterproductive foreign aid policies worldwide.

Emerging out of World War II, the Old Right found themselves in opposition to an emerging interparty consensus between the Democratic Party and their moderate colleagues in the GOP that the United States needed to assume an assertive foreign policy to confront the Soviet Union. Believing that the absence of global American power had ensured the Second World War, this group held that to prevent further catastrophe the United States needed to maintain a large standing military with forward deployments overseas, enmesh itself in multilateral security agreements, and support foreign allies with material and economic assistance.

Conventional histories of the Old Right argue that in the mid-1950s, the GOP’s moderate wing, led by President Eisenhower, supported in this effort by party boosters outside government, effectively marginalized the Old Right. Such is the academic consensus held by scholars such as Justus Doenecke, Michael Hogan, George H. Nash, Paul Gottfried, Aaron Friedberg, and recently, C. William Walldorf. This view holds that the Eisenhower administration’s New Look defense policy plotted a center course which placated the concerns of the Old Right and thereby undercut their resistance.3 As evidence they point to Robert A. Taft’s primary defeat in 1952 and the founding of conservative interventionist magazines like National Review in 1955, arguing that both caused rapid collapses in the noninterventionist right in politics and media.

Contrary to the views of scholars of the early Cold War and American conservatism, I argue that “isolationism” was not decisively defeated by a select group of legislative and executive battles. Instead, it survived in Congress in an attenuated Cold War form that held on to most of its pre-WWII assumptions about America’s role in the world. This redoubt in Congress only disappeared after a decades-long attrition and sometimes conscious culling that resulted from the intraparty struggle between foreign policy factions within the GOP. Regarding the latter, Senate seats vacated via mortality during the critical years from 1945 to 1957 became sites of intraparty dispute. The Old Right and the moderate faction of the GOP struggled over who would fill these vacancies and thereby shape the party’s foreign policy identity. If we center the study of Congress and congressional activity beyond the dates typically associated with conventional narratives and look at the full range of U.S. Cold War policy, we can see that noninterventionist sentiment remained strong within the right wing of the Republican Party throughout the early Cold War.

Why does this distinction between collapse and attrition matter? A longer decline of right-wing noninterventionism suggests that the advent of interventionism and embracing an American-led international order was not an inevitable response to the material conditions of a world destroyed by World War II. The findings of his article suggest that it was instead a conscious cultural and intellectual evolution marked by contingency. Additionally, historians of the early Cold War, such as Campbell Craig, Fredrik Logevall, and Paul A. C. Koistinen, among others, have argued that Cold War belligerence was made possible by the rightward turn of American politics following the Cold War.4 However, applying a quantitative approach to congressional voting records reveals that the right flank of the Republican Party, then still dominated by the Old Right, remained a staunch congressional opponent of critical facets of the emerging Cold War order, defying a president from their party, an emerging bipartisan consensus, and our understanding of what was ideologically conceivable during the early Cold War.

To demonstrate this thesis, this article will use computational methods on a corpus of congressional roll call votes compiled from UCLA’s Voteview database. This dataset comprised 3,680 votes associated with U.S. foreign aid, diplomacy, and military policy from 1935 until 1992. Computational analysis will be used to track the persistence and the decline of noninterventionism within the chambers, the parties, their sections, and wings within the United States Congress. Each roll call was coded into one of three categories: foreign aid, diplomatic policy, or military policy. Foreign aid encompasses all bilateral assistance arrangements concerning humanitarian, economic, or military material support. Diplomatic policy contains all votes that pertain to U.S. bilateral relations with sovereign countries, association with international organizations, or legislative matters concerning U.S. agencies tasked with managing foreign relations. Lastly, military policy contains votes on military programs, appropriations, construction, and conscription.

With each roll call, I determined the vote’s “directionality.” For normal votes, this meant that a “yea” conveyed support for the policy in question. Reverse votes were instances of legislative obstructionism. Such roll calls were intended to derail, limit, or impede the proposed legislation or declaration. Examples include efforts to recommit legislation to committees, efforts to amend bills with limiting language, cut funds, limit geographic scope, establish limits on time, or restrict executive authority. Reverse votes were coded to represent “nay” votes on these roll calls in the same direction as “yea” on normal votes.

To evaluate changing attitudes on U.S. foreign policy I generated percentages of opposition to roll call votes for parties, regions, wings, chambers, and individuals. To generate these statistics, I divided the number of noninterventionist votes by the total vote, thereby generating the proportional statistics for participating members of Congress who voted for noninterventionist policies.5 This formula was applied to parties, party wings, congresses, congressional spans, and individual careers. Due to their noncommitted nature, I excluded abstentions and votes of “present” from these detailed analyses. They are, however, included in graphics that depict longer-term trends at the party level. I also applied these statistics to non-political information, specifically birth years, for cohort analysis purposes.

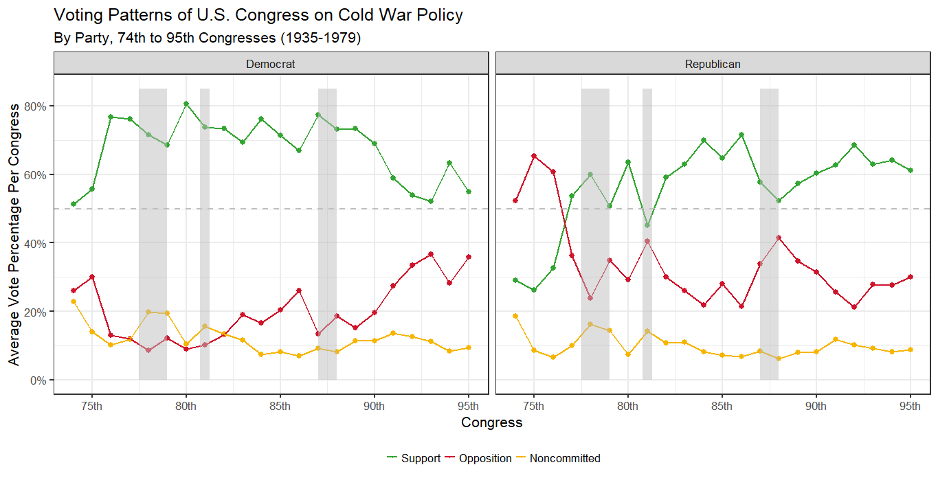

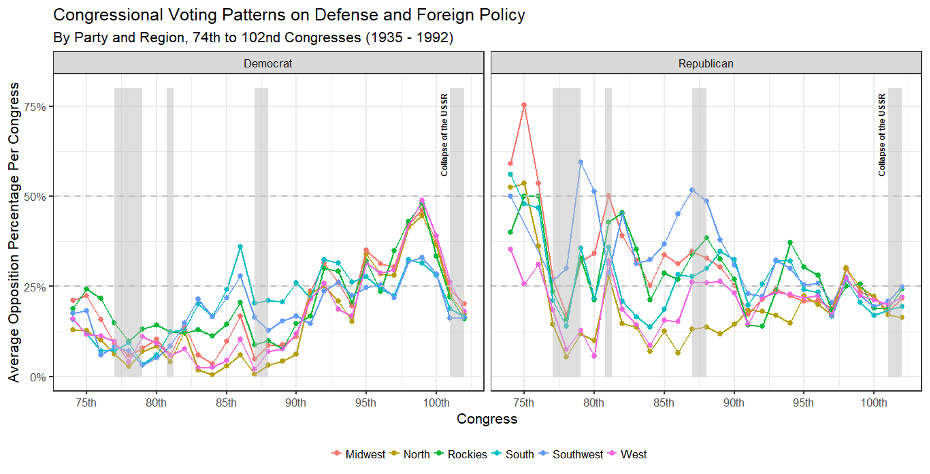

At a macro level, the ideological trajectories of the two major parties went in opposite directions. Republicans became significantly more interventionist upon the end of World War II, except for a flare-up of opposition during the Korean War, causing the GOP to develop into an interventionist party, particularly in the wake of the Vietnam War (Figure 1). Conversely, congressional Democrats went from interventionism’s biggest boosters to its biggest detractors, particularly in the wake of the Vietnam War. These superficial findings comport with commonly understood narratives of America’s domestic political landscape on foreign policy. However, diving one layer beneath the parties, a more complicated picture emerges.

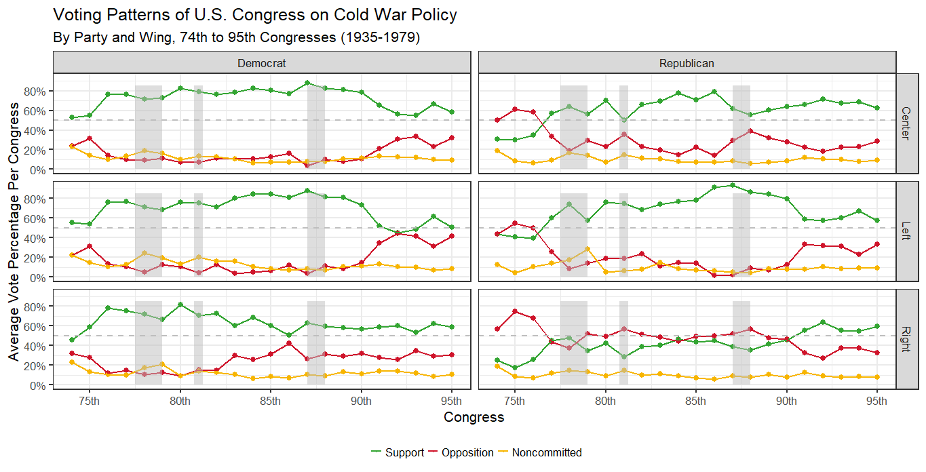

If we facet the voting statistics by the party wings that comprise the two major parties, it becomes apparent that the Old Right of the Republican Party emerged from the Second World War as the least changed political or ideological cohort while liberal and centrist Republicans displayed significantly different voting behavior and went from an oppositional body to a more supportive one. However, from the end of WWII through to the Vietnam War, despite declining in its level of opposition, the Republican Right remained more oppositional on average than supportive (Figure 2). Dividing our statistics into their constitutive parts helps explain why.

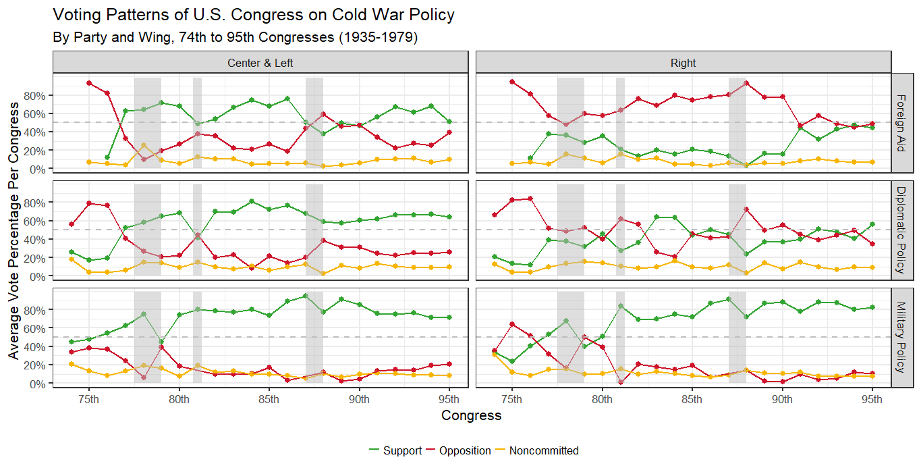

Centering on just the Republican Party and faceting the data between its wings and the types of foreign policy votes, a picture of turmoil and division emerges. Left-wing and centrist Republicans, in the wake of WWII, except for a minor blip during the Korean War, supported all three facets of the emerging Cold War order: military policy, diplomatic policy, and foreign aid spending. The Republican Right, however, displayed unique voting behavior. It supported higher defense spending on the eve of the Korean War while maintaining a complicated relationship with diplomatic policy and a strident and indeed increasing opposition to foreign aid throughout the early Cold War (Figure 3).

Right-wing resistance to defense spending and appropriations fell slightly in the wake of WWII and then dramatically on the eve of the Korean War as once strident right-wing antimilitarists departed Congress or came to recognize a need for elevated defense spending for nuclear deterrence. To resurrect a model of Fortress America from the eve of American entry into WWII, the Old Right advocated for a model of defense spending strictly tailored to hemispheric deterrence. The former president turned conservative political fixer, Herbert Hoover, captured this mood when he advised “arming to the teeth” coupled with a “policy of watchful waiting,” as he had on the eve of WWII.6 Such a view was not unusual, as conservative criticism of a permanent overseas military garrison remained a norm within Congress and segments of the conservative media.7 Despite this conceptual difference regarding the purpose of military policy, only nineteen right-wing Republicans, fourteen Representatives, and five Senators tallied an opposition percentage above 50% on floor votes related to military affairs during the Cold War.8

Despite an evolution in regard to defense spending, the Republican right’s stance on diplomatic policy remained inconsistent throughout the early Cold War. It would not be until the 95th Congress (1977-1979) that support would dependably outpace opposition. In the preceding Congresses, the Republican Right’s stance on diplomatic policy was highly contextual, often related to the nature of the legislation, its impacts on American sovereignty or the growth of executive authority. Of note was the conservative Republican reaction to the Eisenhower Doctrine of 1957, which made the U.S. the dominant power player within the Middle East. One of the doctrine’s opponents, H.R. Gross, argued on the House floor that the legislation “will be the longest single step yet taken toward centralization of government and rule of the Republic by executive decree.”9 While the doctrine’s legislative form, H.J.R 117, passed, it drew 28 Republican dissenting votes in the House and four in the Senate from the party’s right flank. Throughout the early Cold War, the Republican Right attempted to curb executive power, opposed U.S. involvement in multilateral and supranational organizations and supported some bilateral diplomatic initiatives that conserved American unilateralism and sovereignty.

The Republican Right maintained a dogged opposition to foreign aid throughout the early Cold War. While the center of the GOP emerged out of WWII with different voting patterns on foreign aid, throughout the early Cold War, the Republican Right’s opposition never dipped below 50%. In fact, their opposition grew as the showdown with the Soviets progressed and turned towards the postcolonial world during the latter half of the 1950s. Congressional testimony and debate illustrated that the Republican Right opposed American largesse on a combination of fiscal, moral, and racial grounds and sought to derail the foreign aid programs of Republican and Democratic administrations alike. It would not be until the 90th Congress (1967-1969) that a generational turnover changed the political mores of the Republican Right and, therefore, its attitudes towards foreign aid in the Cold War.

While the foreign policy worldview of the Republican Right changed comparatively little during the early Cold War, the larger GOP underwent a significant transformation as the party tacked to the center during the period from WWII until 1970.10 Congressional turnover due to death, retirement, and appointment significantly transformed the Republican Right, particularly in the Senate. While the noninterventionists held their own at the ballot box throughout the early Cold War, those who died in office or decided to retire were replaced by interventionists via appointment or special election. As a cohort, those Republicans who left office via mortality from 1945 to 1957, the critical early years of the Cold War, voted in opposition over 16% higher than those who lost in a general election. The decedents were considerably more conservative than the median Republican during the Eisenhower era than those who left office via electoral defeat (Table 1).

| Reason for Departure | Average Opposition | Average Year of Birth | Ideological Average | Number Departed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Died in Office | 48.50% | 1891 | 0.12 | 23 |

| Did Not Seek Reelection or Retired | 36.40% | 1895 | 0.02 | 61 |

| Defeated in General | 31.80% | 1900 | -0.03 | 74 |

| Resigned, Withdrew, or Expelled | 26.40% | 1901 | -0.20 | 5 |

| Sought Other Elective Office | 22.90% | 1907 | -0.14 | 7 |

| Not Renominated or Lost in the Primary | 21.30% | 1890 | -0.43 | 6 |

This transformation was the starkest in the Republican Senate delegation, which was known in the years before WWII as a hotbed of “isolationism.” Republican Senators, such as William Borah (ID), Gerald Nye (ND), and “Mr. Republican” himself, Robert A. Taft of Ohio, served as roadblocks to American foreign policy in the country’s senior chamber. While a few left DC via the ballot box, like Nye, or converted to interventionism like Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan, eight Republicans with noninterventionist voting records died in office during the critical years of the early Cold War (1945-1957). All eight who left office via the morgue occupied influential committee positions associated with military policy and diplomacy, and only one was ultimately replaced by a like-minded noninterventionist.11

Intraparty struggle between moderate and conservative Republicans over filling these vacancies rapidly transformed the voting habits of the party’s Senate delegation. Such was the case with Nebraska’s Senate seat vacated by Hugh Butler in 1954. Butler had served in the Senate since 1941 and was a reliable no-vote on American foreign policy through WWII and into the Cold War, voting in opposition 65% of the time. The conservative wing of the Nebraska GOP favored former Representative Howard Buffett as Butler’s replacement. Buffett, like Butler, was a reliable voice of opposition to the emerging Cold War order and had in his two stints in Congress from 1943 until 1953 voted in the opposition 62%, opposing everything from defense spending to the draft to American involvement in the Korean War.12

The Eisenhower faction within Nebraska vehemently opposed Buffett’s ascension to the office. They successfully blocked Buffett’s appointment through a placeholder nomination in the form of Samuel Reynolds, who kept the seat warm for their preferred replacement, the more moderate Representative Roman Hruska.13 Hruska won the party nomination later that year and secured the open seat in the 1954 midterms. He served in the Senate for over twenty years and, except for a brief stint of opposition during the height of Vietnam, he served as a consistent vote supporting American foreign policy.14 Such intraparty struggles quickly transformed Republican representation in the Senate so that by the 97th to the 101st Congresses, the height of the Reagan era, the right wing of the Republican Senate tallied an opposition score of 18%, the lowest of any combination of party, wing, or chamber.15

Yet, until the early 1970s, the Republican Right within the House remained a redoubt of noninterventionist sentiment, primarily, as mentioned earlier, on foreign aid and diplomatic policy issues. Except for the disastrous 1964 general election, noninterventionist incumbents, on average, fared no better or worse than their interventionist Republican colleagues.16 From the mid-1950s until the early 1970s, 89 Republican House Representatives averaged 50% or higher opposition to foreign policy throughout their careers, and many of their careers were lengthy. Such longevity demonstrated a continued appetite on the part of the Republican voter for noninterventionist ideas well into the Cold War.17

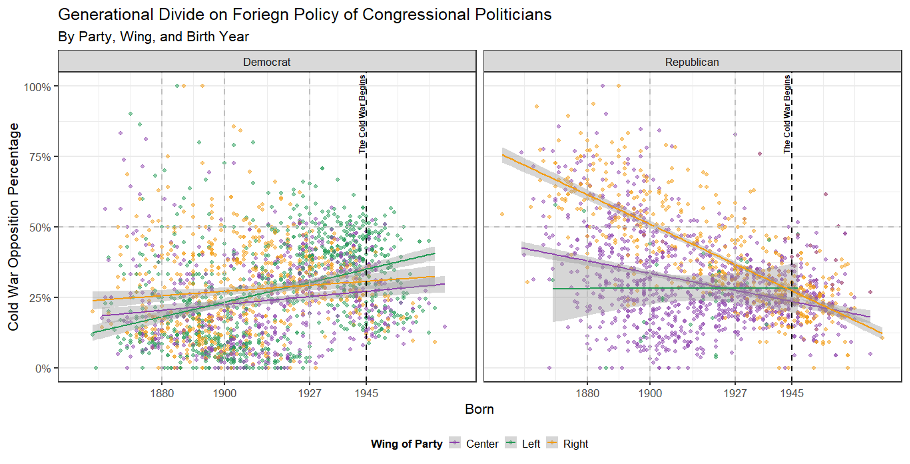

Given the longevity of Republican noninterventionist thinking within the House, could the party’s larger transformation have resulted from a generational divide? A cursory look at the data would suggest so. Arranging members according to the year of their birth versus their career opposition percentage suggests a strong causational link for right-wing politicians between the year of their birth and their voting record on foreign policy.18 Four dates make this relationship intriguing, 1880, 1900, 1927, and 1945 (Figure 5).

If they were born in 1880 or earlier, representatives would have been old enough to have fought in the Spanish-American War and participated in the subsequent American occupation of the Philippines. Intense debate about the American empire outside the Western hemisphere would likely have informed their foreign policy worldview. Many right-wing noninterventionists cited the U.S. occupation of the Philippines as a moment where the American (small r) republican experiment went astray.19

If they were born on or before 1900, representatives would have been old enough to have fought in the Great War. Their foreign policy consciousness undoubtedly would have been formed by this U.S. intervention into European affairs and the sacrifice of American blood and treasure. Also, the intense debates that preceded American entry into the war and the resistance to the Wilsonian vision of an assertive America on the world’s stage would have shaped their perceptions of foreign policy.20

If they had been born before 1927, representatives would have been old enough to have fought in World War II. Their philosophy on U.S. involvement in world affairs would have been informed by another American intervention into Europe and another round of intense debate. However, in this world war, intervention could be justified by the ethical clarity of a defeated fascism, the burdensome history of appeasement, and, in retrospect, the moral weight of the Holocaust.

If they were born after 1945, then representatives would have grown up in an America wrought by the Allied victory in the “good war” and subsequent showdown with the next totalitarian enemy, the Soviet Union. If they were a Republican, they would have likely consumed elite conservative media that eschewed the “isolationism” of yesteryear. New conservative outlets like The National Review (the once noninterventionist), Human Events, and Chicago Tribune all provided a full-throated defense of the Cold War.21 In this new conservative political milieu, the New Right reached full flower in the wake of Vietnam as younger conservatives reacted against an antiwar movement dominated by the left and thereby embraced a war about which older grassroots conservatives were ambivalent.22 In this new world, only six Republicans, four on the right, would meet a 50% opposition threshold throughout their congressional careers.

However, the trend in generational turnover among Democrats was essentially the opposite of Republicans. With a few notable exceptions, the later Democratic politicians were born, the stronger their opposition to U.S. foreign policy.

Generational trends manifested themselves in the elimination of sectionalism in foreign policy. From the interwar period into the early Cold War, foreign policy perspectives were strongly informed by sectional identities in addition to party politics.23 Westerners, particularly Midwesterners especially those within the GOP, were the most opposed to Washington’s foreign policy orthodoxy.24 However, from the 90th Congress onward, the nationalization of American party politics and the political ascent of the New Right narrowed sectional differences within the Republican Party and brought disparate regions into alignment on foreign policy (Graphic 6). After the 97th Congress and the election of Ronald Reagan, the Republican Party was in lockstep.

The Democrats followed a similar trajectory and cohered after a crescendo of sectional difference in the 99th Congress. However, during the 102nd Congress (1991-1993), with the collapse of the Soviet Union, both parties and their sectional components twisted into a narrow Overton Window, creating an unprecedented level of sectional and partisan homogeneity. This uniformity would inform American foreign policy after the Cold War as the U.S. government embraced global hegemony. That is until the pain of twenty years of war, followed by renewed great power competition in recent years, inspired a new generation of conservatives (and progressives) to challenge these recent yet rigid orthodoxies.

Editorial Note

Editorial board member Zoe LeBlanc assumed the role of editor for this article in order to avoid any conflict of interest given that the author was a graduate student at RRCHNM at the time of submission.

Bibliography

Buchanan, Patrick J. A Republic, Not an Empire: Reclaiming America’s Destiny. Washington, DC: Regnery Pub., 1999.

“Congress at a Glance: Major Party Ideology.” Voteview: Congressional Roll-Call Votes Database. Jeffrey B. Lewis, Keith Poole, Howard Rosenthal, Adam Boche, Aaron Rudkin, and Luke Sonnet, 2021. https://voteview.com/.

“Congress Cuts Defense Funds $1.8 Billion.” In CQ Almanac 1963, 19th ed., 141–46. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, 1964. http://library.cqpress.com.mutex.gmu.edu/cqalmanac/cqal63-1316714.

Craig, Campbell, and Fredrik Logevall. America’s Cold War: The Politics of Insecurity. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009.

Doenecke, Justus D. Not to the Swift: The Old Isolationists in the Cold War Era. Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses, 1979.

Dueck, Colin. Hard Line: The Republican Party and U.S. Foreign Policy Since World War II. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Fellers, Bonner. “Military Assistance Program.” Human Events, 27 July 1949, Vol. VI, No. 30. In Bonner Fellers Correspondence 1940–1950, Box 57, Herbert Hoover Post Presidential, Herbert Hoover Presidential Library, West Branch, Iowa.

Garrett, Garet. Ex America: The 50th Anniversary of The People’s Pottage. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Press, 2004.

Gottfried, Paul. Conservatism in America: Making Sense of the American Right. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Gross, H.R. “Foreign Aid: A Form of Glorified Blackmail.” 87th Cong., 1st sess. Congressional Record 107, pt. 7 (1961): 8574.

Gross, H.R. Speaking on H.J. Res. 117. 85th Cong., 1st sess. Congressional Record 103, pt. 1 (1957): 1308.

Halberstam, David. The Best and the Brightest. New York: Ballantine Books, 1969.

Hemmer, Nicole. Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Herbert Hoover to Felix Morley, 18 Dec. 1952. Herbert Hoover Folder, Box 1, Felix Morley Papers, Herbert Hoover Presidential Library, West Branch, Iowa.

Hopkins, Daniel J. The Increasingly United States: How and Why American Political Behavior Nationalized. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Horowitz, David A. Beyond Left and Right: Insurgency and the Establishment. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Katznelson, Ira. Fear Itself. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2013.

Kauffman, Bill. Ain’t My America. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2008.

— America First!: Its History, Culture, and Politics. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1995.

Koistinen, Paul A. C. State of War: The Political Economy of American Warfare. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2012.

Lemelin, Bernard. “A Fiery and Unbated Supporter of Post-War Isolationism: Journalist John T. Flynn and ‘American Foreign Policy, 1945–60.’” Canadian Review of American Studies 49, no. 3 (Winter 2019): 271–301.

Milkis, Sidney M. The President and the Parties: The Transformation of the American Party System Since the New Deal. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Mills, David W. Cold War in a Cold Land. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015.

Mutual Security Act. H.R. 5710. 83rd Cong., 1st sess. Congressional Record 99, pt. 5 (1953): 6891–6903.

Nash, George H. The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945. Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2006.

Nichols, Christopher McKnight. Promise and Peril: America at the Dawn of a Global Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Poole, Keith T., and Howard Rosenthal. Ideology & Congress. Oxford: Routledge, 2007.

Raimondo, Justin. Reclaiming the American Right: The Lost Legacy of the Conservative Movement. Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2008.

Richman, Sheldon. “New Deal Nemesis: The ‘Old Right’ Jeffersonians.” The Independent Review 1, no. 2 (1996): 201–48.

Rothbard, Murray N. The Betrayal of the American Right. Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2007.

Stromberg, Joseph R. “Imperialism, Noninterventionism, and Revolution: Opponents of the Modern American Empire.” The Independent Review 11, no. 1 (2006): 79–113.

Thomas, Clarke. “Course of State GOP May Be Changing: Butler Death May Bring Moderate to Fore.” Sunday Journal and Star, July 4, 1954.

Trubowitz, Peter. Defining the National Interest: Conflict and Change in American Foreign Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Walldorf, C. William, Jr. To Shape Our World for Good: Master Narratives and Regime Change in U.S. Foreign Policy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019.

Westad, Odd Arne. The Global Cold War. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Wiltz, John Edward. “The Nye Committee Revisited.” The Historian 23, no. 2 (February 1961): 211–33.

Notes

-

Gross, H.R. “Foreign Aid: A Form of Glorified Blackmail.” 87th Congress, 1st sess. Congressional Record 107, pt. 7: 8574 ↩

-

On the progressive origins of the Midwestern Republican Right, see Horowitz, David A. (David Alan). Beyond Left and Right: Insurgency and the Establishment. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997. See also, Chapter 4 of Rothbard, Murray N. The Betrayal of the American Right (Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2007) and Richman, Sheldon. “New Deal Nemesis: The ‘Old Right’ Jeffersonians.” The Independent Review (Oakland, Calif.) 1, no. 2 (1996): 201–248. ↩

-

The New Look was a national security policy implemented by the Eisenhower administration. It was centered on deterrence via strategic, theatre, tactical nuclear weapons. The policy was designed to deter the Soviet Union from invading Western Europe and to do so on the cheap. ↩

-

Historian Paul A. C. Koistinen has asserted that the staying power of the military-industrial complex can be explained, in part, by “the conservative turn the nation as taken,” Koistinen, Paul A.C. State of War: The Political Economy of American Warfare (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2012). A common account of the early Cold War asserts that President Truman was “pushed to the right” by his political rivals within the Republican party, particularly those in the so called “China Lobby.” These accounts ignore the significant disorder within the GOP on U.S. foreign policy during the early Cold War and that the strongest political resistance to the early national security in fact emanated from the Republican right. For more conventional accounts see: C. William Walldorf Jr. To Shape Our World for Good: Master Narratives and Regime Change in U.S. Foreign Policy. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019), Craig, Campbell, and Fredrik Logevall. America’s Cold War the Politics of Insecurity (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009). For a dissenting view, read Joseph R. Stromberg. “Imperialism, Noninterventionism, and Revolution: Opponents of the Modern American Empire.” The Independent Review (Oakland, Calif.) 11, no. 1 (2006): 79–113. ↩

-

From the 79th Congress (1945-1947) until the 83rd Congress (1953-1955), the number of rollcall votes on foreign and military affairs remained pretty consistent, although with a slight downward trend, with 44 rollcall votes being recorded in the 79th and 33 in the 83rd. However, beginning in the 84th Congress (1955-1957), as the Cold War ramped up and expanded into the global south, Congress’s roll call votes on foreign affairs doubled to 67. By the 100th Congress, Congress had 290 roll call votes on foreign affairs. ↩

-

Herbert Hoover to Felix Morely 18 Dec 1952, Hoover, Herbert Folder, Box 1, Felix Morely Papers, Herbert Hoover Presidential Library. ↩

-

For specific examples of congressional debate on the U.S. government’s military footprint in Europe and the Republican Right’s opposition thereto, see floor debates on Amendments on the Mutual Security Act, HR 5710, 83rd Congress, 1st sess. Congressional Record 99, pt. 5, p. 6891-6903. For an example of conservative opposition in the media, see Fellers, Bonner “Military Assistance Program,” Human Events, 27 July 1949, Vol VI, No. 30, in Fellers, Bonner Correspondence 1940-1950, Box 57, Herbert Hoover Post Presidential, Herbert Hoover Presidential Library. ↩

-

There was however a small and marginally successfully Old Right effort to cut defense spending related to President John F. Kennedy’s “Flexible Response” defense strategy that sought to diversify American military strategy beyond the confines of nuclear deterrence, a policy opposed by the rightwing of the GOP. See, “Congress Cuts Defense Funds $1.8 Billion.” In CQ Almanac 1963, 19th ed., 141-46. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, 1964. http://library.cqpress.com.mutex.gmu.edu/cqalmanac/cqal63-1316714. For more on Flexible Response and the realignment of defense policy under Kennedy see, Craig, Campbell, and Fredrik Logevall. America’s Cold War the Politics of Insecurity (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009), Halberstam, David The Best and the Brightest, (New York: Ballantine Books, 1969), Westad, Arne Odd. The Global Cold War, (New York: Cambridge, 2007) ↩

-

Gross, H.R., speaking on HJRE 117, 85th Congress, 1st sess. Congressional Record 103, pt.1, p. 1308 ↩

-

Pool, Keith T. and Rosenthal, Howard Ideology & Congress (Oxen: Routledge, 2007). A visualization of these political trends can be seen at: “Congress at a Glance: Major Party Ideology,” https://voteview.com/parties/all Lewis, Jeffrey B., Keith Poole, Howard Rosenthal, Adam Boche, Aaron Rudkin, and Luke Sonnet (2021). Voteview: Congressional Roll-Call Votes Database. https://voteview.com/ ↩

-

Henry Dworshak (career opposition percentage of 62% took the Senate seat that was briefly held by Charles C. Gossett who was appointed to the seat to fill the vacancy left via the death of noninterventionist stalwart, John Thomas (career opposition percentage of 65%). ↩

-

Buffett’s only Congress of marginal support was the 78th Congress (Jan 1943-Jan 1945) when WWII was at its height during which he voted in opposition at a clip of 29%. ↩

-

For a narrative of this intraparty struggle see Thomas, Clarke. “Course of State GOP May Be Changing: Butler Death May Bring Moderate to Fore,” Sunday Journal and Star, 4 Jul 1954 ↩

-

From 1953 until 1976, Roman Hruska voted in opposition 40% of the time. However, from the 91st Congress (1969-1971) onward, Hruska’s opposition fell rapidly. From the 91st Congress until his final Congress, the 94th, Hruska only voted in opposition 20% of the time. ↩

-

The core reason for this massive change was personnel turnover not changes in voting behavior by individual members. Only two Republican Senators who began their careers in the final years of the Eisenhower administration (or earlier), when the Old Right was still a visible political force, served long enough to witness the start of the Reagan administration. Those two Senators were Barry Goldwater (AZ) and Strom Thurmond (SC). Goldwater and Thurmond are rare examples of conservative Republicans whose foreign policy voting habits went from significant opposition to high degrees of support later in their careers. They are, however, exceptions, as by the time of the Reagan revolution, the Old Right had disappeared from electoral politics. Conversely, the Democrats demonstrated considerable continuity, with 15 Senators (and 24 House members) whose careers bridged this span. ↩

-

From 1950 until 1962, Republican House incumbents with career opposition percentages of 50% or higher performed roughly as well as their party colleagues with interventionist voting habits, those who recorded less than 50% opposition throughout their careers. Both cohorts beat the incumbent reelection average five times in those seven elections. The two exceptions for both were the 1954 and 1958 midterm elections. It appears that during the formative years of the Cold War, noninterventionist incumbents were as electorally viable as their interventionist colleagues. ↩

-

The aforementioned H.R. Gross served in the House for 26 years (1949-1975). A number of his colleagues served similarly lengthy terms. Alvin O’Konski represented Wisconsin’s 10th district for over 30 years (1943-1973), Ben F. Jensen served Iowa’s 7th congressional district for 26 years (1939-1965), and the eccentric ideologue James B. Utt of California, who was elected in 1952 served until his death in 1970, to name a few. ↩

-

On the issue of ideological transformations within Congress, political scientists Keith T. Poole and Howard Rosenthal contend that “changes in Congressional voting patterns must occur almost entirely through the process of replacement of retiring or defeated legislators with new blood.” Pool, Keith T. and Rosenthal, p.102. Their research suggests that the evolution of U.S. foreign policy attitudes may also be determined by member replacement. ↩

-

For a recent version of the “America gone astray” argument see Buchanan, Patrick J. A Republic, Not an Empire: Reclaiming America’s Destiny (Washington, DC: Regnery Pub., 1999). For a contemporary example, see Garret, Garet Ex America: The 50th Anniversary of the People’s Pottage (Caldwell: Caxton Press, 2004). Other scholars have noted that the Old Right political tradition had antecedents in American resistance to the Spanish-American War and the subsequent occupation of the Philippines. See: Lemelin, Bernard. “A Fiery and Unbated Supported of Post-War Isolationism: Journalist John T. Flynn and “American Foreign Policy, 1945-60,” Canadian Review of American Studies, Volume 49, Number 3, Winter 2019, pp. 271-301 and Nichols, Christopher McKnight, Promise and Peril: American at the Dawn of a Global Age (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011). Minnesota Representative turned Senator Ernest Lundeen was an example of noninterventionist whose foreign policy views were shaped by their military service in Spanish-American War. ↩

-

Examples of World War I informing the worldview of the Old Right are too numerous to list here. However, for some examples, see Hemmer, Nicole. Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), p.10, Wiltz, John Edward. “The Nye Committee Revisited,” The Historian, February 1961, Vol. 23, No. 2 (February 1961), pp. 211-233, and Chapter 5 of Rothbard, Betrayal of the American Right. ↩

-

Heterodox narratives from figures inside or sympathetic to the Old Right cite the primacy of these events in their intellectual isolation of the postwar Republican Party. For examples of such accounts see, Kauffman, Bill Ain’t My America (New York, Metropolitan Books, 2008) and America First! It’s History, Culture, and Politics (Amherst, N.Y: Prometheus Books, 1995), Rothbard, Murray N. The Betrayal of the American Right (Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2007), Raimondo, Justin. Reclaiming the American Right: The Lost Legacy of the Conservative Movement (Wilmington, Del: ISI Books, 2008). For academic accounts of this period see Doenecke, Justus D. Not to the Swift: The Old Isolationists in the Cold War Era (Cranbury, Associated University Presses, Inc, 1979), Dueck, Colin. Hard Line: the Republican Party and U.S. Foreign Policy Since World War II (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2010), Nash, George H. Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945. (Wilmington: ISI Books, 2006) and Gottfried, Paul Conservativism in America: Making Sense of the American Right (PALGRAVE: New York, 2007). ↩

-

See: Katznelson, Ira Fear Itself (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2013), Mills, David W. Cold War in a Cold Land (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015), Trubowitz, Peter Defining the National Interest: Conflict and Change in American Foreign Policy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1998) ↩

-

For this article, Midwestern states are defined as Illinois, Nebraska, Minnesota, Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, South Dakota, Missouri, North Dakota, and Kansas. Western states include California, Montana, Oklahoma, Nevada, Idaho, Texas, New Mexico, Wyoming, Oregon, and Alaska. Northern states: New York, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Vermont, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island. The South is defined as Alabama, South Carolina, West Virginia, Mississippi, Kentucky, Virginia, North Carolina, and Louisiana. Since the District of Columbia does not possess voting representation in Congress, it is not included in this analysis. ↩

-

For more on the nationalization of American politics see Hopkins, Daniel J. The Increasingly United States: How and Why American Political Behavior Nationalized (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2018), and Milkis, Sidney M. The President and the Parties: The Transformation of the American Party System Since the New Deal (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993). ↩

Author

Brandan P. Buck,

Cato Institute, bbuck@cato.org,