Visualising Art on the Threshold in the Palazzo Medici, Florence

Abstract

Filippo Lippi’s c.1450-53 lunette-shaped Annunciation panel, today in London’s National Gallery, was made to be displayed in the Palazzo Medici in Florence, built in the mid-fifteenth century for Cosimo the Elder de’ Medici and his family (figure 1). It is now widely agreed that this panel—as well as its pair, depicting Seven Saints—originally functioned as a sovrapporta (overdoor), positioned at one of the thresholds inside the palazzo.1 While significant scholarly attention has been paid to Lippi’s iconographic choices in this Annunciation,2 and theories have been put forward regarding which doorway it crowned,3 little has been made of the painting’s liminal location and its effect upon viewing experience and possible interpretations. In this paper, I will outline how analysing Lippi’s Annunciation as a boundary marker, encountered when navigating an elite domestic interior, is advancing understanding not only of the painting itself but also of the relationship between life, space and art inside the Florentine palazzo. With a rudimentary 3D model of the Annunciation reinstated as a sovrapporta, I will begin to explore the possible use of animated digital simulations as a means of reactivating the role of artworks intended for liminal and/or transitional spaces.

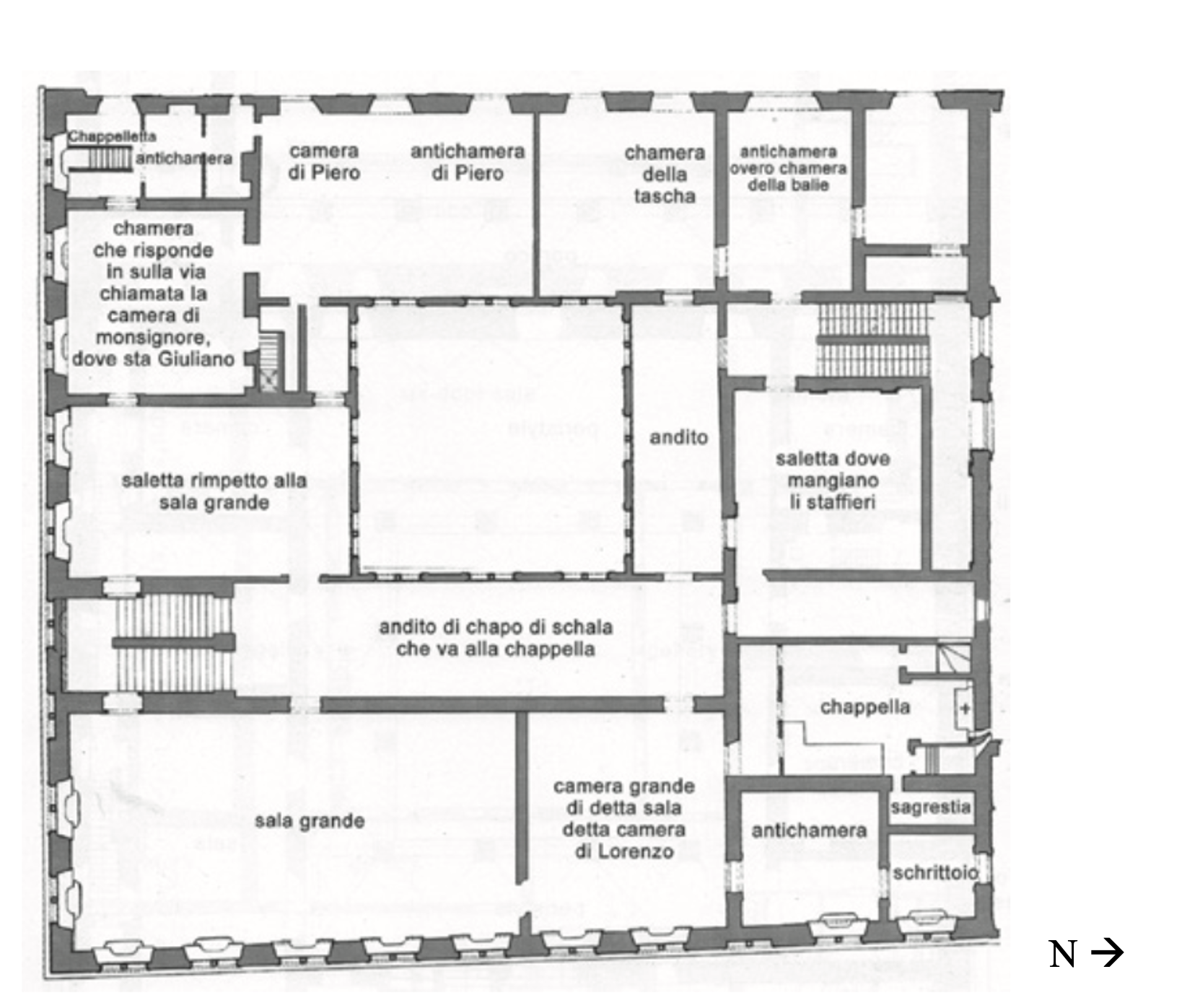

Whether conducting traditional art-historical research or gathering sources for a digital model, it is necessary first to consider what is known—and what is not known—about the original location of the Annunciation within the Palazzo Medici. It is likely to have been positioned somewhere in the east wing of the piano nobile (the main floor, above the ground floor), as this was the suite of rooms occupied by Piero de’ Medici, who is widely held to have commissioned the two Lippi lunettes.4 However, the 1492 inventory of the property does not list either painting (probably because they were seen as arredi fissi—fixed decor, set into door architraves—rather than enumerable mobili, moveable furnishings), so their exact site within the wing is unknown.5 By mapping the overdoor artworks that were listed in the inventory onto the thresholds marked on an extant floorplan from 1650, the possible sites of the Annunciation and its pair can be narrowed down by a process of elimination [figure 2].6 Yet, however closely we might be able to pinpoint on the floorplan the original positioning of the sovrapporta, the architectural and decorative specificities of the painting’s surroundings remain unknown: the Palazzo Medici has undergone extensive remodelling in the last five to six hundred years, particularly in the years following the palazzo’s purchase by the Riccardi family in 1659, which has entirely transformed much of the piano nobile.7 Therefore, when discussing the overdoor function of Lippi’s Annunciation and creating a digital model of its original context, precise reconstruction of the visual environment is not currently a viable aim.8 Rather, the study will be advanced by considering the type of embodied viewing experience that might have been possible in this space, and by a close reading of the painting itself.

Liminal Contexts: The Architectural and Symbolic Threshold

Walking through the piano nobile of the Palazzo Medici’s east wing in the fifteenth century would have involved a series of stops and starts, progress made or denied by a combination of physical and social boundaries. For some, passing over these thresholds was a daily occurrence; for others, a special privilege; and for others still, a social impossibility, whether due to their status, gender, or some other excluding factor.9 Even the apartment’s occupants—Piero de’ Medici when the palazzo was first built, later his son Lorenzo—would have been given to pause: nowhere was out of bounds to them, of course, but their progress through the space would rarely have been a measured, unidirectional motion into the ever smaller rooms. In particular, the paths woven were punctuated by the opening and closing of doors, which enforced a moment of pause before granting advancement. Overdoor artworks such as Lippi’s Annunciation would have helped guide this procession into privacy, often endowing the places of passage with symbolic meaning or resonance.

The contemporary viewer approaching the Annunciation would have immediately understood the symbolic suitability of this religious subject matter to the painting’s threshold positioning. The Annunciation story revolves around boundaries, intact and breached: the Archangel Gabriel physically crossed into the Virgin’s inner sanctum to deliver news of her impregnation, while at the same time the Holy Spirit crossed into the Virgin’s body. Moreover, the Virgin (or her womb – the two were usually conflated) was often described using architectural metaphors. Sometimes, she was specifically characterised as a door or gate, whether a “porta clausa” (“closed door”)10 or “porta coeli” (“door [or gate] of heaven”).11 Setting the scene in what appears to be a porch or loggia would have had a compositional as well as symbolic function.12 Such structures are simultaneously open and closed, inside and outside, and thus afford the spectator visual access to the Virgin’s private quarters—while still suggesting her cloistered existence. 13 For the composition to succeed, her privacy is inevitably performative rather than literal.

The liminal symbolism of Lippi’s Annunciation would also have had a local dimension, part of the lived experience of the fifteenth-century viewer. Not only was the Feast of the Annunciation on March 25 celebrated as the entry into the new year in the Florentine calendar, but visual precedents (and their strategic locations) across the city would also have exemplified the subject’s liminal associations: the tradition of placing images of the Annunciation next to buildings’ (particularly churches’) entrances and exits functioned as well-timed pictorial reminders of the Savior’s entry into the world for the sake of humanity.14 Reassuring and perhaps also admonitory, this message thus greeted worshippers upon entry to a sacred space or was the last thing they saw before re-entering the secular bustle of the street beyond. A fourteenth-century Annunciation fresco next to the exit of the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata was actually believed to be miraculous, spawning many similar artworks across the city and firmly embedding the iconography and this positioning in the popular psyche.15

Towards an Embodied Analysis of Lippi’s Paintings

The above analysis goes some way to recovering the “period eye” through which the Annunciation was viewed, to use Michael Baxandall’s term for the associations and experiences the original spectator would have brought to the perception and comprehension of an artwork.16 However, there are other aspects of the original function and reception of the painting that are harder to recapture: as a sovrapporta, the panel would have been installed at a height of over two metres.17 Its height alone, though, would not have created exceptional viewing conditions, as domestic artworks were often hung very high, above beds, spalliera wall panelling or some other piece of furniture.18 Perhaps hardest to recover is the fact that the painting in this liminal position would most often have been interacted with in motion, too, from a viewpoint that shifted as the spectator approached the threshold.

The creation of a basic 3D model, using the computer graphics application Autodesk Maya, has helped begin the process of reinstating the original experiential context of the Annunciation (figure 3). Such a digital visualisation is not a mere illustration of prose analysis, but it is also a tool by which I hope to test theoretical assumptions and conjectures about the impact of space and movement on viewing artwork in the domestic interior. It is important to emphasise, however, that the simulation seen here is not intended as a research output, or for use beyond this specific art-historical experiment.

The model is a simple cuboid structure, a necessarily “blank” interior space given current uncertainty about the identity and location of the room in question.19 Placing the doorway on the short wall proposes it as a connector between two rooms of an apartment suite, two spaces to be traversed in succession. The dimensions of the aperture (198 x 93 cm) and the basic design of the doorframe are based on that of the fifteenth-century doorway leading from the vestibule to the chapel on the piano nobile of the Palazzo Medici.20 Thus Lippi’s overdoor, at 153 cm wide, easily spans the threshold. While some sovrapporte were simply propped atop the door’s architrave, it is thought that Lippi’s panel was actually embedded into the moulding of the door—hence the architectural frame that surrounds it in this model. To simulate the fourth, temporal dimension of the mobile act of viewing, a camera is set up within the model, at roughly eye-height (156 cm), which can be manually guided towards the threshold in an approximate rendering of the approach of a historical resident or visitor.

Looking Up and Moving Forwards: The Model in Action

By using this model as the vehicle through which Lippi’s Annunciation is analysed, the relationship between the embodied act of viewing and the visual properties of the painting itself can be better conceptualised. In many cases, the act of looking up and walking forwards would accentuate qualities of the artwork already legible when it was decontextualised; in others, it seems that these viewing conditions might actually have created effects otherwise not discerned. In general terms, the sense of spatial recession would have been intensified by the relatively low position and forward motion of the viewer (and, of course, this viewing angle became rapidly sharper as the spectator got nearer to the threshold).21 The viewer’s position would also have rendered more prominent the exceptionally low-flying dove in the painting, and have offset the impression of its “plummeting,” to use Leo Steinberg’s description.22

The perspectival grid delineated by the marmo finto (fake or imitation marble) paving stones in Lippi’s painting leads the eye back, to various spaces visible behind the Virgin and Archangel. In the center of the composition, up two steps and through an open doorway, can be seen a staircase, the first steps rising to the right before disappearing from view. Especially with the hand of God appearing in a deep blue cloud above them, these stairs might indicate a heavenly ascent (of the spectator’s contemplation, perhaps, or of the Virgin herself, towards whom the stairs point).23

These glimpsed slivers of space in Lippi’s Annunciation also have a simpler function, exciting the eye with the evocation of rooms and life lying just out of visual reach. This effect is accentuated in our case example: not only was the panel itself positioned on a threshold inside the Palazzo Medici, but the painted scene itself is set in a contemporary palazzo environment. Perhaps the most crucial glimpsed space, narratively and symbolically, is that in the shadows behind the Virgin, where a bed can be made out. It was increasingly common for artists to situate the Virgin’s bedroom beyond the main stage of action, rather than inviting the viewer directly into the privacy and intimacy of her thalamus (a term used to refer to the Virgin’s bridal chamber).24 Choosing to depict this space as a palazzo’s luxurious camera (chamber, often bedchamber), though, might have been specifically intended to heighten a visitor’s anticipation before stepping into the next room of the piano nobile, itself undoubtedly as luxurious as the one Lippi renders in painted form.25 The Virgin’s lettiera (bed) is a splendid piece of furniture, decorated with a gilded, intarsiated foliage design, and covered in a deep blue-and-gold brocade.

Knowing exactly which threshold the painting crowned might yield fascinating insights into the relationship between Lippi’s camera and the nature of the real space and furniture of the palazzo which would be encountered next door—whether or not such connections were intended when the painting was first made.26 In general terms, though, it can already be seen that the bed and textiles in the painting are similar to some of those described in fifteenth-century inventories consulted.27 The subject matter and composition of this Annunciation may also have reminded a visitor of what a privilege it was—an almost sacred privilege, perhaps—to be allowed to penetrate this far into the Medici inner sanctum.

Our digital model might provide the impetus to connect Lippi’s illusionistic spaces with the panel’s real surroundings, but it currently lacks the architectural and decorative specificity to contribute to this part of the analysis. Already, though, it is possible to draw some specific conclusions about how the Annunciation’s composition was received by the original spectator, thanks to the sense of directional and mobile viewership the model conjures. The pictorial space occupied by the Virgin and Archangel, who are already arranged close to the picture plane, actually seems to merge with real space as the viewer moves forward and the garden path separating the two on the left-hand side disappears from sight. Moreover, where many Annunciations of the Tuscan tradition physically divide the space between the two figures with a column or wall, here the emblem-carved parapet and the vase of lilies on it act as a visual accent rather than any sort of impediment to the Archangel’s progress. In fact, the vertical axis is marked most emphatically not by a solid but by a concavity (in the form of the doorway leading to the stairs). Thus, the closer the visitor or resident was to the threshold, the stronger the impression would have become that the Virgin and Archangel were parting, heads bowed, to let the approaching person pass through. Indeed, the concavity in the painting would probably have aligned with the place where the double-leaf door below opened, leaving one figure crowning each side.28

Future Directions

So far, the 3D digital model has proved a valuable analytical tool when unpacking the relationship between artwork and domestic space in the Palazzo Medici in the fifteenth century. Not only has it allowed me to interrogate ideas otherwise restricted to the theoretical, but the very act of producing this simulation has also sent me in new directions of inquiry. As Diane Favro puts it, “The act of making the model is integral to knowledge creation.”29

However, as previously emphasised, this is only a first foray into the application of digital humanities techniques to the re-contextualisation of early modern artworks; both the research and the model are in their early stages. Moreover, the model is not research-based in any structured, systematic way, or underpinned by metadata, and areas of uncertainty (of which there are many, given the gaps in our knowledge outlined above) are neither rendered visible nor linked to explanatory notes. To become a publishable research output, a model of Lippi’s overdoors in context would require cross-disciplinary collaboration with digital modelling specialists and the adoption of a clear and flexible ontology.30

Only then might this work be harnessed for the museum public, probably in the form of an AR experience.31 Further collaboration with locative and augmented reality media specialists would be necessary to develop an in-gallery application, providing yet more exciting opportunities to develop an integrated workflow between disciplines. In the National Gallery’s permanent collection, attempts to recontextualise the Annunciation and its pair—by hanging them high up, or over a doorway, for instance—would be disruptive to the overall harmony of the hang and would likely lack historical rigour. With an AR application, the gallery-based user would be able to explore the reconstructed palazzo environment using real movements, anchored around the real painting.32 Complementing rather than substituting the value of close and extended looking at the art object itself, the experiential dimension of the digital offering would thus become literal and immersive.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

L’inventario dei beni e delle masserizie esistenti nel palazzo di via Larga, 1492 (1512 copy). Archivio Mediceo avanti il Principato, Archivio di Stato di Firenze, filza 165.

English translations given here are taken from Stapleford, Richard, ed. and trans. Lorenzo de’ Medici at Home: The Inventory of the Palazzo Medici in 1492. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2013.

Secondary Sources

Ajmar-Wollheim, Marta, and Flora Dennis, eds. At Home in Renaissance Italy. V&A Publishing, 2006.

Ames-Lewis, Francis. “Art in the Service of the Family: The Taste and Patronage of Piero Di Cosimo de’ Medici.” In Piero de’Medici ‘Il Gottoso’ (1416-1469): Kunst Im Dienste Der Mediceer: Art in the Service of the Medici, edited by Andreas Beyer. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1993.

Ames-Lewis, Francis. The Early Medici and Their Artists. Birkbeck College, University of London, 1995.

Baxandall, Michael. Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style. Oxford University Press, 1972.

Bolard, Laurent. “‘Thalamus Virginis.’ Images de la ‘Devotio moderna’ dans la peinture italienne du XV^e^ siècle.” Revue de l'histoire des religions 216, no. 1 (January-March 1999): 87-110.

Bulst, Wolfger. “Die ursprüngliche innere Aufteilung des Palazzo Medici in Florenz.” Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 14, no. 4 (1970): 369-392.

Büttner, Frank. “‘All'usanza moderna ridotta’: gli interventi dei Riccardi.” In Il Palazzo Medici Riccardi di Firenze, edited by Giovanni Cherubini e Giovanni Fanelli, 150-168. Giunti, 1990.

Ciardi Dupré Dal Poggetto, Maria Grazia. “I Dipinti di Palazzo Medici nell’inventario di Simone di Stagio delle Pozze: Problemi di Committenza e di Arredo.” In La Toscana al Tempo Di Lorenzo Il Magnifico: Politica - Economia - Cultura – Arte. Vol. 1, 131-162. Convegno di studi promosso dalle Università di Firenze, Pisa e Siena, 1992. Pisa: Pacini Editore, 1996.

Cooper, Donal, Fabrizio Nevola, Chiara Capulli and Luca Brunke. “3D models and locative AR: Hidden Florence 3D and experiments in reconstruction.” In Hidden Cities: Urban Space, Geolocated Apps and Public History in Early Modern Europe, edited by Fabrizio Nevola, David Rosenthal and Nicholas Terpstra. Routledge, 2022. <doi.org/10.4324/9781003172000-15>.

Davies, Martin. “Fra Filippo Lippi’s Annunciation and Seven Saints.” Critica d’Arte 3, no. 8 (January 1950): 356-363.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. Fra Angelico: dissemblance et figuration. Flammarion, 2009.

Duits, Rembrandt. “Figured Riches: The Value of Gold Brocades in Fifteenth-Century Florentine Painting.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 62 (1999): 60-92. <doi.org/10.2307/751383>.

Edgerton, Samuel. “‘How Shall This Be?’ Reflections on Filippo Lippi’s ‘Annunciation’ in London.” Part II. Artibus et Historiae 8, no. 16 (1987): 45-53. <doi.org/10.2307/1483299>.

Favro, Diane. “Se non è vero, è ben trovato (If Not True, It Is Well Conceived): Digital Immersive Reconstructions of Historical Environments.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 71, no. 3 (September 2012): 273-277. <doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2012.71.3.273>.

Flint, Alisdair. “Building the Virgin’s House: The Architecture of the Annunciation in Central and Northern Italy 1400-1500.” PhD diss., University of York, 2014.

Gnocchi, Lorenzo. “Le Preferenze Artistiche di Piero di Cosimo de’Medici.” Artibus et Historiae 9, no. 18 (1988): 41–78. <doi.org/10.2307/1483336>.

Gordon, Dillian. The Fifteenth Century Italian Paintings. Vol. 1. London: National Gallery, 2003.

Holmes, Megan. “The Elusive Origins of the Cult of the Annunziata in Florence” In The Miraculous Image in the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance, edited by Erik Thunø and Gerhard Wolf. L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2004.

Hood, William. Fra Angelico at San Marco. Yale University Press, 1993.

Lillie, Amanda. “Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting.” The National Gallery, London. Published online 2014. www.nationalgallery.org.uk/research/research-resources/exhibition-catalogues/building-the-picture.

Lillie, Amanda. Florentine Villas in the Fifteenth Century: An Architectural and Social History. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Marchini, Giuseppe. Filippo Lippi. Electa, 1979.

Morolli, Gabriele, Cristina Acidini Luchinat, and Luciano Marchetti, eds. L'architettura di Lorenzo il Magnifico. Silvana editorial,1992.

Morrison, Jo. “Hidden Florence 3D at the National Gallery.” Calvium. December 5, 2019. calvium.com/hidden-florence-at-national-gallery-overview/.

Nevola, Fabrizio, Donal Cooper, Chiara Capulli, and Luca Brunke. “Immersive Renaissance Florence: Research-Based 3-D Modeling in Digital Art and Architectural History.” Getty Research Journal, no. 15 (2022): 203-2. <doi.org/10.1086/718884>.

Nevola, Fabrizio, Donal Cooper, Chiara Capulli, and Luca Brunke. “Research-based 3D Modelling of Santa Maria degli Innocenti: Recovering a Context for the Quattrocento Altarpieces.” In Common Children and the Common Good: Locating Foundlings in the Early Modern World, edited by Nicholas Terpstra. Florence: Villa I Tatti and Istituto degli Innocenti, 2022 (forthcoming).

Preyer, Brenda. “Planning for Visitors at Florentine Palaces.” Renaissance Studies 12, no. 3 (September 1998): 357–74, <doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-4658.1998.tb00415>.

Jeffrey Ruda, Fra Filippo Lippi: Life and Work with a Complete Catalogue. Phaidon, 1993.

Scudieri, Magnolia. The Frescoes by Angelico at San Marco. Giunti for Firenze MVSEI, 2004.

Shearman, John. Only Connect: Art and the Spectator in the Italian Renaissance, A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, 1988. Princeton University Press, 1992.

Steinberg, Leo. “‘How Shall This Be?’ Reflections on Filippo Lippi’s ‘Annunciation’ in London.” Part I. Artibus et Historiae 8, no. 16 (1987): 25-44. <doi.org/10.2307/1483298>.

Vasari, Giorgio. Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architetti. Vol. 4. Le Monnier, 1848.

Verdon, Timothy. Maria nell'arte Fiorentina. Mandragora, 2002.

Notes

-

This article presents some of the author’s early doctoral research into the liminal and transitional spaces of fifteenth-century Florentine palazzi, a more advanced version of which will later form part of a thesis chapter. This PhD is an AHRC-funded Collaborative Doctoral Project, co-supervised by Fabrizio Nevola at the University of Exeter and Caroline Campbell at the National Gallery, London. The author is also a member of Florence 4D, a research group whichexplores the use of digital technologies – namely 3D modelling and GIS mapping – to enhance understanding of the art and architecture of Renaissance Florence. The previous suggestion that the panels might have been originally installed as bedheads—Marchini, Filippo Lippi, 206; Ames-Lewis, The Early Medici and Their Artists, 120—has by now generally been abandoned. Not only were bedheads much more commonly rectangular, but the bedheads listed in contemporary Medici inventories were more than double the width of these panels. Gordon, The Fifteenth Century Italian Paintings, 155. Both panels were purchased just before 1848 from the Palazzo Medici by the Metzger brothers, Florence-based art dealers. This provenance note is published in an 1848 edition of Vasari’s Vite. 118, note 3. ↩

-

Davies, ‘Fra Filippo Lippi’s Annunciation and Seven Saints’; Steinberg and Edgerton, ““How Shall This Be?”” Parts I and II. ↩

-

Ciardi Dupré Dal Poggetto, “I Dipinti di Palazzo Medici nell’inventario di Simone di Stagio delle Pozze,” 149–50. ↩

-

While Davies is more tentative in discussing specifically which member of the Medici family might have commissioned the work, Ames-Lewis persuasively argues that it was Piero. Ames-Lewis, “Art in the Service of the Family,” 208–11. ↩

-

The inventory of the whole palazzo was taken in 1492, following the death of Lorenzo de’ Medici. This inventory is now lost, and it is a 1512 copy that has come down to us: L’inventario dei beni e delle masserizie esistenti nel palazzo di via Larga. Jeffrey Ruda discusses the absences of Lippi’s lunettes: Ruda, Fra Filippo Lippi, 446. Those overdoor paintings included in the inventory seem to be the ones which were independently framed and moveable. For example, in the Sala Grande, there was ‘a painting on canvas above the door of the room […] with a gilt frame, depicting a figure of Saint John, by Andreino [Andrea del Castagno]’ and ‘a painting on canvas above the door of the room […] with a gilt frame, depicting lions in a cage, by Francesco di Pesello [Pesellino]. L’inventario, fol. 13v. ↩

-

Wolfger Bulst was the first to map the rooms listed in the inventory onto this floorplan (Bulst, “Die ursprüngliche innere Aufteilung des Palazzo Medici in Florenz”); now we are mapping artworks from the inventory onto this floorplan. It can be deduced, for instance, that a threshold of the scrittoio (study) was actually unlikely to have been the site of Lippi’s panels, even though this is a commonly held assumption (see note 3). The 1650 floorplan shows that the scrittoio, as the last in the apartment’s suite of rooms, could be entered and exited through only one doorway, which connected it to the anticamera (it shared a wall but not a door with the small sacristy, and the opening on the north wall was a service door). Moreover, an entry in the 1492 household inventory lists ‘a marble panel over the study door with five antique figures’ (fol. 16v); even if one of Lippi’s paintings had been installed on the other side of this door – to be approached by someone moving from the scrittoio to the anticamera – these two pieces of information weaken the suggestion of a close visual and spatial connection between the Annunciation, the Seven Saints and the objects in Piero’s study. ↩

-

See Frank Büttner, ““All'usanza moderna ridotta.”” ↩

-

More precise reconstruction of other spaces in the Palazzo Medici, such as the ‘camera grande terrena’ once occupied by Lorenzo de’ Medici, is a longer-term aim of this research and one of the projects to be conducted in conjunction with Florence 4D (see introductory note). ↩

-

On the relationship between residents and visitors in patrician domestic interiors, see Preyer, “Planning for Visitors at Florentine Palaces.” ↩

-

This metaphor for Mary was very common in the period: it derives from the closed door, accessible only to God, in Ezekiel’s vision of the temple, Ezekiel 44:1-3. ↩

-

She is thus described, for instance, in the medieval hymn “Ave maris stella.” See Verdon, Maria nell'arte Fiorentina. ↩

-

Where the Annunciation took place was not specified in the scriptures and thus invited artistic invenzione when setting the scene, within the limits of decorum. ↩

-

Lillie, “Apertures and arches, porches and loggias” in Building the Picture. ↩

-

Flint, “Building the Virgin’s House,” 23–35 (and throughout). ↩

-

Holmes, “The Elusive Origins of the Cult of the Annunziata in Florence”. Also in the 1450s, Piero de’ Medici commissioned Michelozzo to build an ornate tabernacle around the Annunciation fresco at SS Annunziata, further enhancing its miracle-working fame. See Lorenzo Gnocchi, “Le Preferenze Artistiche di Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici,”. At least four copies of this fresco were made, including one next to the exit of the church of Santa Maria Novella. See Flint, “Building the Virgin’s House,” 23–26. ↩

-

Michael Baxandall first explores the concept of the ‘period eye’ in Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy. ↩

-

Brenda Preyer’s extensive measuring of extant doors in Renaissance Florence has led to her to conclude that sala–camera doors were around 3m high, while doors leading to the anticamera or scrittoio were nearer 2.5m. Findings cited in Ajmar-Wollheim and Dennis, At Home in Renaissance Italy, 274-275. ↩

-

Ajmar-Wollheim and Dennis, At Home in Renaissance Italy. 274. ↩

-

The length of this ‘room’ is undetermined (i.e. the cuboid is open-ended), while its width is modelled at 5m, a broad estimate based on the approximate width of some of the smaller rooms in the piano nobile’s principal apartments (as deduced from the 1650 floorplan). Its height is assumed from the ceiling height of the chapel’s vestibule (see note 20). As we do not know the placement of windows relative to the direction of travel, lighting is rendered as frontal rather than from the left or right. ↩

-

The vestibule-chapel doorway is crowned by Benozzo Gozzoli’s Mystic Lamb fresco. This seems to be the only door-and-overdoor ensemble which survives from the period of construction. The measurements of this aperture are given in Morolli et al, L'architettura di Lorenzo il Magnifico, 126. The estimated height of the doorway in the model also accords with the results of Brenda Preyer’s extensive measuring of extant Renaissance doors in Florence. See note 17. ↩

-

Georges Didi-Huberman noted a similar—if more drastic—effect in Fra Angelico’s Annunciation fresco for the Corridor of the Lay Brothers at the Convent of San Marco, which the Dominican friars would have approached by ascending a staircase. He went so far as to argue that, upon reaching the painting, the friar would have to further lower his viewpoint, ‘kneeling chastely’ to perform the Ave Maria, in order for the painting to gain “perspectival coherence.” Didi-Huberman, Fra Angelico: dissemblance et figuration, 269, 284, 418 (my translations). Here Didi-Huberman develops the ideas first posited by William Hood. More recent studies of the architectural composition reveal that the painted space does not actually ‘adhere to any hard and fast [perspectival] rules’, though this does not entirely invalidate the embodied readings of Hood and Didi-Huberman. Scudieri, The Frescoes by Angelico at San Marco, 39, 42. ↩

-

The dove’s positioning probably relates to Lippi’s esoteric depiction of divine conception. See Steinberg and Edgerton, ‘“How Shall This Be?”: 25–53. Viewing the artwork from below would also have lessened the effect of apparent misalignment of the vase of lilies upon the parapet. This strange imbalance in the centre of the painting, which has long puzzled art historians, deserves future investigation using digital modelling methods: approaching the threshold not only from below but also from the right might have caused the vase and parapet to align correctly, if only momentarily (though the rest of the composition would in turn have been distorted from such an oblique angle). This would lend support to John Shearman’s belief that, despite the ‘seeming accidentality’ of his ‘grasp of perspective’, Lippi actually ‘adjusted at will the stereometry of form to situate the beholder’. Shearman, Only Connect, 70. If this is the case, the implications are important: the creation of this near-anamorphic effect would suggest that Lippi had precise knowledge of the intended site of the commission, and might also help us deduce further which doorway on the piano nobile the painting decorated (one which the viewer approached, say, having rounded a corner, or having entered the preceding room from a different angle). ↩

-

Christa Gardner von Teuffel believes that the inclusion of the flight of stairs in Lippi’s Palazzo Medici Annunciation could suggest that the panel was originally situated at the top of a flight of stairs, though this is unlikely. Her idea is cited in Gordon, The Fifteenth Century Italian Paintings, 155. ↩

-

For further discussion of this term, see Bolard, “Thalamus Virginis.” ↩

-

On the contrast between the humble dwelling of the Virgin described in the scriptures and the luxurious settings of fifteenth-century Annunciations, see “A Room of her Little House: The Problem of Mary’s Poverty,” in Flint, “Building the Virgin’s House,” 108–116. Depictions of the Annunciation regularly transposed the scene to a location which echoed the actual architectural and social context of the commission. Perhaps most famously, Fra Angelico’s Annunciation at the Convent of San Marco, painted the decade before Lippi’s work, includes an ascetic cloister and verdant garden closely based on the religious complex of San Marco itself. ↩

-

More than fifty years separate the painting of Lippi’s Annunciation and the inventory taken following Lorenzo’s death, during which time the furnishings and decoration of the palazzo’s rooms would have changed (to a greater or lesser extent). Moreover, we do not know if Lippi had precise knowledge of the intended site of the commission (see note 22). Furthermore, we should not attempt to read the painting’s setting as a clue to its original location in the palazzo. Not only did many rooms in Florentine palazzi include beds, such that deducing which type of room’s threshold the painting crowned would be limited, but also the interiors depicted in paintings were rarely unmediated reflections of real space. ↩

-

Rembrandt Duits actually seeks to link the fine textiles depicted in the Annunciation paintings Lippi produced for the Medici to those described in family inventories. Duits, “Figured Riches.” ↩

-

Similar to this was a fourteenth- and fifteenth-century decorative trope, found particularly in church interiors, which saw the Annunciation composition positioned across the spandrels of an archway, such that the fictive architectural setting of the Virgin’s domain gave way to ‘real-world’ void in the centre. Perhaps the most famous example of this type of Annunciation is Giotto’s c.1305 fresco of the subject painted across the chancel arch of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. ↩

-

Favro, “Se non è vero, è ben trovato,” 275. ↩

-

A promising interdisciplinary collaboration, this time to model the fifteenth-century interior of Filippo Brunelleschi’s Santa Maria degli Innocenti, is discussed in Nevola et al, “Immersive Renaissance Florence.” See also Donal Cooper et al, ‘Research-based 3D modelling of Santa Maria degli Innocenti: recovering a context for the Quattrocento altarpieces’, in Nicholas Terpstra ed., Common Children and the Common Good: Locating Foundlings in the Early Modern World, Villa I Tatti and Istituto degli Innocenti, 2021 (forthcoming). ↩

-

The recontextualisation of another National Gallery artwork, Jacopo di Cione’s fourteenth-century altarpiece for the church of San Pier Maggiore, was successfully transformed into a public-facing, in-gallery AR experience. See Cooper et al, “3D models and locative AR.” And Morrison, “Hidden Florence 3D at the National Gallery.” ↩

-

As described in relation to the San Pier Maggiore altarpiece case study. Morrison, “Hidden Florence 3D at the National Gallery.” ↩

Author

Anna McGee,

University of Exeter, A.Mcgee@exeter.ac.uk,