A Monarch in Motion: Mapping the King's Private Correspondence

Abstract

Christian IV’s writing room is still more or less preserved in Rosenborg castle, Copenhagen (figure 1).1 While this wonderfully sets the scene for the seventeenth-century epistolary practices, the number of letters written from this location is only a small part of the very extensive correspondence maintained by the Danish king.

Christian IV of Denmark (1577–1648, r.1588–1648) was indeed an avid writer, putting his thoughts on paper in journals, diaries, and letters.2 As King of Denmark, he lived an itinerant life, moving through his territories on a regular basis. He left a significant stamp on the built heritage throughout the Danish territory, including parts of current Germany, Norway, and southern Sweden as well as more remote territories like the Faroe Islands and Greenland.3 This territory was so vast that it seems unlikely that Christian IV visited all the places under his authority. Despite his prominent role in Danish history and built heritage, research on the Danish monarch has remained relatively obscure, partly because of language issues.4

Digital tools help to surmount the difficulty of foreign languages. Christian IV was the author of a large body of correspondence, totaling over 3000 still preserved letters.5 In recent years, increasing efforts have been made to digitize and transcribe extensive collections of archival documents, including correspondence, making them available online and thus accessible for data-driven analysis on large corpora.6 In this paper we will establish a methodology to deal with large bodies of correspondence, focusing on geographic information and the data that can be extracted from these writings. We will apply this methodology to a sample of Christian IV’s extensive correspondence, using Named Entity Recognition and Linking combined with a Geographic Information System to look at the mobility of the Danish king and his writings considering different locations, including his many building projects. Through this analysis we will attempt to unearth personal preferences and patterns in his mobility.

The Corpus

The corpus consists out of 865 letters, handwritten by Christian IV that are transcribed and published online.7 This online collection of letters is only part of the large body of correspondence produced by the Danish king. More letters are available in the seven volumes published by Bricka and Fridericia in the nineteenth century, not considering letters that might have been lost over time. Our analysis is based on the digitized collection, so conclusions must be taken carefully. The aim is to illustrate the digital methodology for which the partial collection is sufficient.

To perform a distant reading of Christian IV’s correspondence we collected the letters as separate txt files from their online environment.8 The transcription was done by Bricka and Fridericia in the nineteenth century, and there is metadata including the receiver, place, and date of sending, attached to each letter (when known). The letters are written mostly in German, but letters in Danish as well as Latin are also included in the corpus. Taking a closer look at the corpus, we see that the transcription is generally of good quality, but it remains truthful to the original handwritten letters. The inconsistent German spelling of the seventeenth century is thus something we will need to take into account. The time frame ranges over the entire lifetime of Christian IV, with a focal point on his later life, especially from 1625 onwards. Recipients vary from royal confidants and ambassadors, like Corfitz Ulfeldt or Christen Friis, to his second wife, Kirsten Munk.

Mapping the Royal Itinerary

The attached metadata allows for a mapping of the place of sending of the letters, using QGIS, a free and open-source Geographical Information System (GIS).9 Contrary to his contemporaries, Christian IV wrote most of the letters himself, signing each one with a date and place of sending (figure 2).

While other kings and nobles often used scribes for their correspondence, it was customary for Christian IV to sign letters personally, often adding date and location to the signature.10 Since all the letters in the corpus were handwritten and signed by Christian IV, this allows us to place the Danish king at a certain location at a certain point in time, based on his signature. The resulting attribute table (see table 1) shows 568 entries that have both geographical and temporal data attached to them. This analysis is thus based on a subset of the digitized collection. That inevitably means that there are important lacunae in our data, for example the visits to England – that Christian IV undertook in 1606 and 1616 – are not represented here.11

| 67 | Christian 4. | Kirsten Munk | Haderslev | 55,250000 | 9,500000 | 1615-08-24 |

| 68 | Christian 4. | Kirsten Munk | Wolfenbüttel | 52,162222 | 10,536944 | 1615-09-01 |

| 69 | Christian 4. | Elisabeth af Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel | Celle | 52,625556 | 10,082500 | 1615-11-03 |

| 70 | Christian 4. | Kirsten Munk | København | 55,676111 | 12,568889 | 1615-12-14 |

| 71 | Christian 4. | Kirsten Munk | Frederiksborg | 55,935000 | 12,300833 | 1615-12-27 |

| 72 | Christian 4. | Ellen Marsvin | Kronborg | 56,038611 | 12,621944 | 1615-07-10 |

| 73 | Christian 4. | Sivert Pogwisch and Joachimvon Mitzlaff | Rotenburg | 49,377222 | 10,178889 | 1615-12-01 |

| 79 | Christian 4. | Johan Sigismund af Brandenburg | Kronborg | 56,038611 | 12,621944 | 1617-09-07 |

| 85 | Christian 4. | Ellen Marsvin | København | 55,676111 | 12,568889 | 1618-08-15 |

| 90 | Christian 4. | Johan Frederik af Slesvig-Holsten-Gottorp | Glückstadt | 53,788889 | 9,425833 | 1619-09-25 |

| 94 | Christian 4. | Unknown | Frederiksborg | 55,935000 | 12,300833 | 1621-08-31 |

| 95 | Christian 4. | Unknown | Frederiksborg | 55,935000 | 12,300833 | 1621-09-24 |

| 98 | Christian 4. | Unknown | København | 55,676111 | 12,568889 | 1622-02-25 |

| 109 | Christian 4. | Hans Lauritsen and NielsKnudsen | Nyborg | 55,309722 | 10,791667 | 1623-07-01 |

Through a mapping of this information, we can see that Christian IV travelled through much of the seventeenth-century territory of Denmark, which included Schleswig-Holstein (current northern Germany), southern Sweden, and Norway (figure 3).

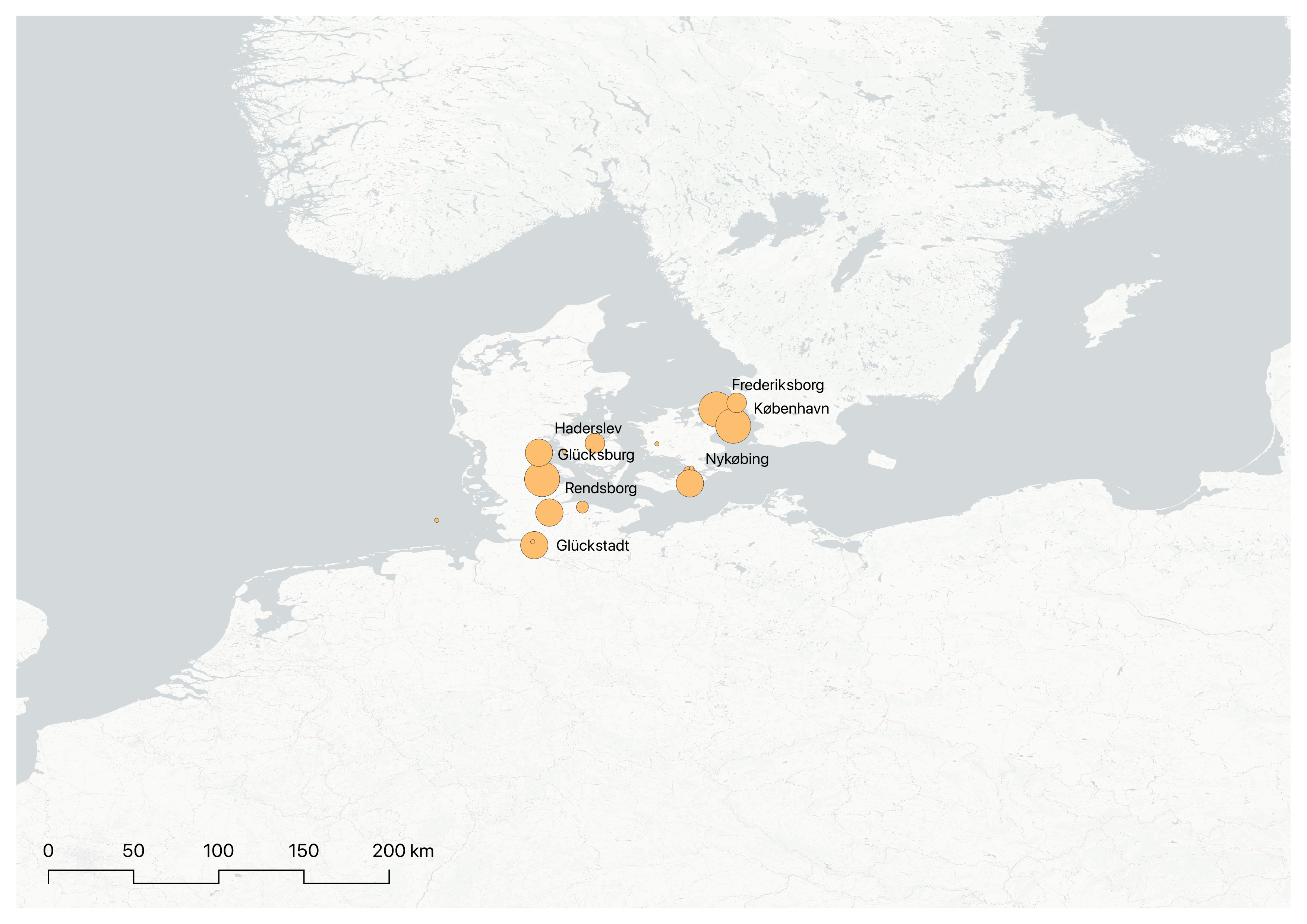

This first map, however, does not show how many letters were written from a certain location. By visualizing the weight, i.e., the number of letters written from a certain location, we can correlate the itinerary of Christian IV with the network of residences that served him in his peregrinations.12 This allows us to filter out most- and least-visited residences, and link these with the functions and responsibilities of the Danish king and events during his lifetime. In this visualization a bigger dot means that more letters were sent from a certain location and that Christian IV spent a relatively larger amount of time there. The map is thus a representation of the focal points in his itinerary (figure 4). We can clearly distinguish the capital city Copenhagen and Frederiksborg, one of his largest construction projects. However, other locations—further away from the Danish capital—are also included, for example Glückstadt and Wolfenbüttel.

With the aim of reconstructing the network of residences of Christian IV of Denmark in mind, we want to use this visualization to reveal patterns or evolutions in time of the king’s use of his residences. By splitting up the dataset into relative periods of time, we can see some interesting transformations (figure 5). With the limited dataset we have very few letters from before 1626, which clearly shows in the earliest maps. There is no discernable focal point, and Christian’s mobility spread out over Denmark and the German lands. After Denmark joined the Thirty Year’s War, however, we see both an increase in letters and a spreading of Christian’s presence towards the south. He spent considerable amounts of time in Wolfenbüttel and Rothenburg. From 1630 onwards, the Danish involvement in the Thirty Year’s War ceased, and Christian focused his presence on the Danish lands, with focal points in Jutland as well as Sealand. During the final years of his life, he mostly stayed for long consecutive periods of time in Frederiksborg and Copenhagen (presumably Rosenborg).

The digital analysis of Christian IV’s handwritten letters and their associated geographical and temporal data offers a unique window into the Danish king’s travels. Through the visual representation of letter frequencies, we uncover the significance of critical locations in his life, shedding light on the evolving priorities and commitments over time.

A Distant Reading of Locations

We can now place Christian IV of Denmark in space and time through the analysis of the place of sending of his letters. We are, however, also interested in what Christian IV has to say about these locations and his building projects within the text of his letters. In order to read through this large collection of correspondence, we will first build a gazetteer based on the corpus. A gazetteer is a dictionary of historical place names that can include information and certain characteristics of that location. By using Natural language processing (NLP) we get access to a wide range of possibilities to analyze linguistic attributes of a text corpus. NLP allows users to convert data into usable insights, by determining whether a word is a verb or a noun, and even whether it is a location, geographical entry, or a person through Named Entity Recognition. We will use the NLP library spaCy to detect the place names mentioned in the corpus of correspondence.13 Because of the different layers of distortion caused by language (mixing Danish and German, as well as the inconsistent early modern spelling), we decided to use two pretrained models provided by spaCy: both the German and Danish models trained on newspaper articles. The resulting tab-separated value file is run through the World Historical Gazetteer (WHG), where we can “reconciliate” with Wikidata. This process of reconciliation links the place names in our own gazetteer to places that are included in the WHG and a unique identifier in Wikidata. After the automatic reconciliation process is complete, you are given the option to manually match the ambiguous place names. The resulting dataset, including the geographical coordinates, can be downloaded from the WHG and together with the places of sending of the corpus of correspondence, this becomes the gazetteer that we will use for the further analysis. We again used QGIS to map out the locations included in our gazetteer. Our visualization now covers a noticeably larger area of Europe, going as far as Spain and England and covering the German lands to a greater extend.

As in our first map visualization, we can add weight to the locations by counting the number of times they are mentioned within the corpus of correspondence and adjust the size of the dots accordingly (figure 6). The center of gravity is still in Denmark, especially on the island of Sealand, and a number of locations in Schleswig-Holstein. However, looking at the table, we now see that Rosenborg, for example, becomes quite important, with thirty-one mentions within the corpus of the letters. In our first analysis, Rosenborg was completely absent, which seems abnormal since this was one of Christian’s building projects. This might have been because Christian signed his letters with “Københav” when he was at the castle in Rosenborg, or because the letters that are part of the online collection were allocated ‘Copenhagen’ as location metadata, while the actual place of sending was Rosenborg. Indeed, on closer inspection of the original texts, there are forty-eight letters written and signed from “Rossenborg” This more detailed analysis of the content of the letters draws our attention to inaccuracies in the metadata, which can be corrected through an iterative process.

The Building projects

The collection of correspondence of Christian IV gives a privileged view on his life and reconstructed personal life stories. The digital methodology allows us to reconstruct Christian IV’s itinerary and investigate whether his peregrinations were determined by personal agency or political necessity. The localization of the sites of his building projects shows that he did still very much live an itinerant lifestyle, compared to other royal families in Europe, and that he even put in considerable time, money, and effort into expanding his residential and urban networks (figure 7).14

Satellite residences appear in the vicinity of Copenhagen, but also on the edge of the Danish territory, settlements are established to house the king and his travelling household.13 The living circumstances and possibilities to live a more withdrawn life were highly contingent on location, since there was such a large diversity of locations in the network supporting Christian IV. Along the way he stayed in cloisters, busy court cities, and large domains with extensive gardens, parks, and forests. More in-depth research on these individual locations would allow us to add additional metadata to the geographic points, for example, on the size of the apartment, the extent of the domain, and the possible hosts. Putting this information as readable metadata attached to the geographic locations, we could analyze, filter, and visualize even more aspects of the itinerant lifestyle of Christian IV.

However, we can also use our previously built gazetteer to filter out information about the different locations. SpaCy also allows us to analyze the context in which the locations occur by looking at the words close to certain gazetteer entries. Through this analysis, often referred to as concordance matching, we can learn what words appear frequently in relation to certain locations. This abstract analysis then allows us to dive deeper into certain word combinations, which is how we know – for example - that the king’s room at Rosenborg needed to be heated before his arrival.

The different building projects were an important topic within the corpus of Christian IV’s letters, and sometimes they even included instructions for architectural interventions, as was the case for a letter addressed to the Danish diplomat Friederich Günther (1581–1655). It contained instructions on how to alter the residences at Segeberg and Wandsbeck, specifically that in Segeberg the connection (i.e., the corridor and staircase) between the king’s stube and the room for his chamberlain should be closed up.15 Diving deeper into the actual text of the letters based on the locations gives us a glimpse of the lives lived within the walls of the royal residences at different locations.

Conclusion

The digital tools used remain tailored to modern research questions and vocabularies, making the adaptation to early modern source material challenging. The free open-source library for natural language processing (spaCy) provided pre-trained models in a wide range of languages, including Danish and German. However, the model was trained on written web text making it less accurate for analysis on early modern source material. Thanks to the high-quality transcription we did manage to obtain 688 hits for the Named Entity Recognition (locations, geographical entities, and persons). Nevertheless, training a model on seventeenth-century Danish sources might give more and better (more accurate) results. For example, “Oldenburg” kept popping up as a location, which within the context of Christian IV’s correspondence refers to the House of Oldenburg, the dynasty of which Christian IV was a part. It does not give information about Christian IV’s presence in Oldenborg. Similarly, references to England and Spain could be part of a name, rather than a reference to the location. In addition, the references to these territories are represented by points located in Londen and Madrid respectively, while a polygon covering the entire territory would be more appropriate.

While network analysis is generally accepted as a methodology to deal with epistolary practices, I believe this methodology focused on geographical locations can also be generalized and applied to other collections of correspondence. The analysis was now limited to the 865 letters that have been digitized on the Danmarks Breve website. The corpus can be enlarged if the other letters written by Christian IV and published in the nineteenth century become included in the online environment.16 A larger corpus would allow more detailed analysis and could also include research on other phenomena, such as seasonal migration.

Bibliography

Bricka, C. F., and J. A. Fridericia, eds. Kong Christian den Fjerdes Egenhændige Breve. Forlagt af Universitetsboghandler, 1889-91.

Daybell, James, and Kim McLean-Fiander, eds. Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO). Accessed March 27, 2022. http://emlo-portal.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/collections/?page_id=2595.

Grunewald, Susan, and Andrew Jaco. “Finding Places with the World Historical Gazeteer.” Programming Historian 11, 2022. https://doi.org/10.46430/phen0096.

Hotson, Howard, and Miranda Lewis, eds. Early Modern Letters Online (EMLO). Accessed March 27, 2022. http://emlo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk.

Det Kongelige Bibliotek. “Danmarks Breve.” Accessed April 20, 2022. https://danmarksbreve.kb.dk/.

Digitale Undersøgelser af Dansk Sprog (DUDS) - University of Copenhagen. “Christian IV’s breve (1615-1642).” Accessed April 20, 2022. https://duds.nordisk.ku.dk/tekstresurser/dsst/teksterne/christian-ivs-breve/.

Kongernes Samling Rosenborg. “Christian IV’s Writing Room.” Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.kongernessamling.dk/en/rosenborg/room/christian-ivs-writing-room/.

Kragelund, Patrick. A Stage for A King. The Travels of Christian IV of Denmark and the Building of Frederiksborg Castle. Museum Tusculanum Press, 2019.

Lockhart, Paul Douglas. Denmark, 1513–1660: The Rise and Decline of a Renaissance Monarchy. Denmark, 1513–1660. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Maekelberg, Sanne. “Mapping through Space and Time. The Itinerary of Charles of Croÿ (1560‐ 1612).” In Mapping Historical Landscapes in Transformation: Methods, Applications, Challenges, ed. Thomas Coomans, Bieke Cattoor, and Krista De Jonge, 259–76. Leuven University Press, 2019.

Paravicini, Werner, Kruse Holger, Ranft Andreas, and Klaus Krüger.’“Ordonnances de l’Hôtel” und “Escroes des gaiges” wege zu einer prosopographischen Erforschung des burgundischen Staats im fünfzehnten Jahrhundert.” In Menschen am Hof der Herzöge Von Burgund: Gesammelte Aufsätze, 41–63. Thorbecke, 2002.

Rigsarkivet København, Kongehuset Christian 4., Christian 4.segenhændige breve.

Roding, Juliette Germaine. “Christiaan IV van Denemarken (1588-1648): Architectuur En Stedebouw van Een Luthers Vorst.” University of Nijmegen, 1991.

Senning, Calvin F. “The Visit of Christian IV to England in 1614.” The Historian 31, no. 4 (1969): 555–72.

spaCy. “Industrial-Strength Natural Language Processing.” Accessed April 20, 2022. https://perma.cc/E7L8-Y8YH.

QGIS. “QGIS – The Leading Open Source Desktop GIS.” Accessed April 20, 2022. https://www.qgis.org/nl/site/.

Notes

-

“Christian IV’s Writing Room,” https://www.kongernessamling.dk/en/rosenborg/room/christian-ivs-writing-room/. ↩

-

Lockhart, Denmark, 1513-1660, 127. ↩

-

“Christian IV,” https://kongeligeslotte.dk/en/explore-history/christian-IV.html ↩

-

Christian IV is considered ‘Rex Triumphans’, the most famous Danish king throughout history, most of the literature on Christian IV is in Danish: Stein, Christian den Fjerdes Billedverden; Heiberg, Christian 4. – en europæisk statsmand; Scocozza, Christian IV. Some notable exceptions: Heiberg (ed.), Christian IV and Europe; Andersen et. Al (eds.), Reframing the Danish Renaissance; Lockhart, Denmark in the Thirty Years’ War, 1618–1648. ↩

-

The original letters are currently kept in the Danish State Archives in Copenhagen: Rigsarkivet, Kongehuset Christian 4.,Christian 4.s egenhændige breve. They were published in seven volumes in the nineteenth century: Bricka and Fridericia,Egenhændige Breve. ↩

-

For example: Howard Hotson and Miranda Lewis, eds., Early Modern Letters Online (EMLO),https://emlo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk, accessed 27 March 2022 and James Daybell and Kim McLean-Fiander, eds., Women’s Early Modern Letters Online (WEMLO), https://emlo-portal.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/collections/?page_id=2595, accessed 27 March 2022. ↩

-

Danmarks Breve, https://danmarksbreve.kb.dk/?f%5Bsender_ssim%5D%5B%5D=Christian+4.&q=Christian+4.&search_field=Alle+felter.A smaller sample is also available through the DigitaleUndersøgelser af Dansk Sprog (DUDS) of the University of Copenhagen:https://duds.nordisk.ku.dk/tekstresurser/dsst/teksterne/christian-ivs-breve/. ↩

-

With thanks to Alexander Bugge Stage and the Royal Danish Library. ↩

-

“QGIS”, https://www.qgis.org/nl/site/. ↩

-

For example, this was also the case for Charles of Croÿ, see: Maekelberg, “Mapping through Space and Time,” 259-276. ↩

-

Senning, “The Visit of Christian IV,” 555–72; Kragelund, A Stage for A King. ↩

-

According to Paravicini and Kruse, length and frequency of stay are paramount in defining which residence is ‘important’ and which is not: Paravicini, et al., ‘“Ordonnances de l’Hôtel” und “Escroesdes gaiges,”’ 41–63. ↩

-

See https://perma.cc/E7L8-Y8YH for documentation on the SpaCy library. Susan Grunewald and Andrew Janco have written a tutorial on how to use NLP and Python to distil place names from a corpus:https://programminghistorian.org/en/lessons/finding-places-world-historical-gazetteer#4-building-a-gazetteer. ↩ ↩2

-

For example, by that time the King of Spain, Philip III, had established a fixed summer and winter residence. ↩

-

“Auss demselbigen Obersten Lossomenthe Soll Ein ganck ihn den Runden torm gemacht werden, also dass ihn dem dii Slaffkammer seyn kan. Dess graffuen kammer soll zu dem kammer Iuncker Oder kammerdiner gebra[u]chet werden, vndt der ganck von meiner Stuben dahrein gehen, vndt dii treppe, Dii Itzo dahrzu hinauffen gehet, soll weckgebrochen oder zugemauret werden,”https://danmarksbreve.kb.dk/catalog/%2Fletter_books%2F002207661%2F002207661_007-L0022076610070094#kbOSD-0=page:1. ↩

-

Another option would be to scan the books and run them through Optical Character Recognition (OCR), but that would include a long manual process of cleaning noisy text. The volume with letters from the period 1632-1635 is available on Google Books, which could serve as a test case for this approach.https://books.google.dk/books?id=D3YBAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=nl&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false ↩

Author

Sanne Maekelberg,

Center for Privacy Studies, sma@teol.ku.dk,