A Digital Reconstruction of Privacy in the Royal Apartments? Network Theory and the 1585 court ordinance of Henri III of France

Abstract

In 1530 Francis I, King of France from 1515 to 1547, claimed that “in no other Christian monarchy existed a greater conglutination, bond, and conjunction of true love than between the Kings of France and their subjects.”1 2 As we learn from King Louis XIV (1638-1715), this bond of true love expressed itself in the subject’s easy and free access to the prince.3 While the French monarchy prided itself on its public character and (relatively) high accessibility, this pride has sometimes mistakenly been understood as a limited or non-existing presence of privacy at the French court.4

While privacy remains a slippery concept, Orlin defined personal privacy as taking many forms, including interiority, atomization, spatial control, intimacy, urban anonymity, secrecy, withholding, and solitude.5 In architectural history, it has been argued that the increased room specialization found in early modern castles and country houses resulted from a growing need for privacy.6 While Orlin contests this idea, she nevertheless agrees that privacy can relate to the concept of spatiality.7 The spatiality of privacy, in turn, often follows the recognition of a public versus a private sphere.8

The French court was indeed known for the relatively high accessibility of the king’s ‘personal’ spaces, as vocalized by Michele Soriano in 1562.9 A letter written by Henri III’s mother Catherine de’ Medici (1519-1589) in 1576 nevertheless also makes clear that during the reign of Charles IX (1550-1574) and Henri III (1551-1589), the fine line between desired access and disorder had been crossed.10 Henri III was therefore encouraged to return to the time-honored ways of his father Henri II (1519-1559) and grandfather Francis I, where one could assume a more organized familiarité was present. Henri III seems to have agreed with his mother about the existing chaos, but different from her wish and the courtiers’ expectations to return to the previously employed accessibility, Henri III ‘dreamed of a monarchy magnified by distance (and) of an inaccessible sovereign.11

Using network theory and the 1585 court ordinance of Henri III of France (1551-1589), this article reconstructs and measures the spatiality of privacy at the French court. Most of all, this article demonstrates how network theory can overcome some limitations of access diagrams by integrating additional source material, like court ordinances, and with this, reach a better understanding of accessibility and the spatiality of privacy at court.

Access Analysis

In the 1990s, network theory found its way to the field of archaeology in, among others, the form of access diagrams. Where network theory studies graphs as representations or relations of objects in the form of nodes or vertices and edges, access analysis uses this theory to represent the configurational relations between spatial elements and their connectivity.

Access analysis developed from the gamma analysis introduced by Hillier and Hanson in their book The Social Logic of Space (1984). This technique was used to investigate the relationship between spatial order and society by looking at the patterns of relations between inhabitants and strangers as reflected in the use of interior space through patterns created by boundaries and entrances.12 Hillier and Hanson argued that spatial organization is a function of the form of social structure. While this argument was critically received, their technique of visualizing the relation between enclosed spaces through their connection to each other by passageways in a diagram was appropriated in access diagrams.13

The application of access diagrams (Fig. 1) is beneficial in deepening the understanding of a building’s spatial layout and creating awareness of the different degrees of accessibility. However several complications have limited the technique’s adoption in archaeology and architectural history. First, access diagrams require a complete dataset on the exact structure of the building, including all the enclosed spaces and their partitions. To make an access diagram, one either needs to depart from a still extant and “complete” building or base oneself on plans and descriptions. Unfortunately, it is only in specific cases that this information sufficiently exists. Another constraint of access analysis, as was formulated by Hanneke Ronnes, is that its application is time consuming and “not very straightforward.”14

Despite these constraints, in cases where enough information is available to reconstruct a building’s spatial layout, access analysis is a valuable technique. It represents the first step toward a better understanding of accessibility. Nevertheless, to reconstruct a building’s accessibility in detail and formulate the spatiality of privacy, access diagrams alone are not enough. From their structure, access diagrams imply that privacy is always gradually obtained following the progression of spaces. In other words, they imply that with every space one enters “deeper” into a residence, the degree of accessibility and privacy changes accordingly. Actual accessibility and privacy, however, do not necessarily have to follow the progression of enclosed spaces and can also take place abruptly. An “undeep” or shallow space can be equally private as or even more private than a “deep” space depending on the measures of accessibility at play.15

Furthermore, access diagrams only represent a static representation of accessibility. In reality, the degree of accessibility of a particular space or a set of rooms can change depending on the time of day, the inhabitant, or the company.16 Thus, in order to reach an informed notion of the spatiality of privacy at a particular residence, one needs to account for these variables by including additional source material. In this article, I demonstrate how court ordinances can serve this purpose.

Regulating Court Life

Notwithstanding the relatively easy accessibility of the French court, it was from the reign of Henri II (1519-1559) at the latest—and further elaborated under Henri III—that an increasing proportion of court life became regulated through court ordinances.17 This article focuses on the Règlement general de 1585 of Henri III, which belongs to a group of three independent court regulations issued in 1574, 1578, and 1585.18 Their goal was to remettre l’ordre et police at the court of Henri III of France.

According to Werner Paravicini, court ordinances can be defined as “regulations issued by a nobleman or ruler determining (1) the offices in the household, (2) who is to hold these offices, (3) the payment provided, (4) what has to be done and (5) how this needs to be done.19 However, most court ordinances only contain a selection of the above-described elements and deal with normative provisions for the household in general and not a specific person or residence.20 Since they deal with normative provisions, one has to realize that these documents do not necessarily reflect reality. Instead, they should be seen as an idealized description or aspired situation. Despite their limitations and pitfalls, court ordinances nevertheless provide court historians with valuable insights into social structures, ceremonies, rules of conduct, and spatial distributions of the court, which can rarely be obtained from other sources.21 For the reconstruction of the spatiality of privacy at the French court, the 1585 ordonnance is specifically helpful, as it provides us with information on the ideal structure of the royal apartments, the King’s activities and whereabouts during the day, as well as the space specific conditions and rules of conducts that needed to be followed by the courtiers.

Through the translation of this data into a network, (1) an abstract reconstruction of the King’s use of space during the day was made, (2) degree of accessibility of the royal apartments based on the courtiers’whereabouts was visualized, and (3) the King’s use of these spaces to their degree of accessibility was compared to define the spatiality of privacy present at the French court as was envisioned by the King himself in 1585.

Method

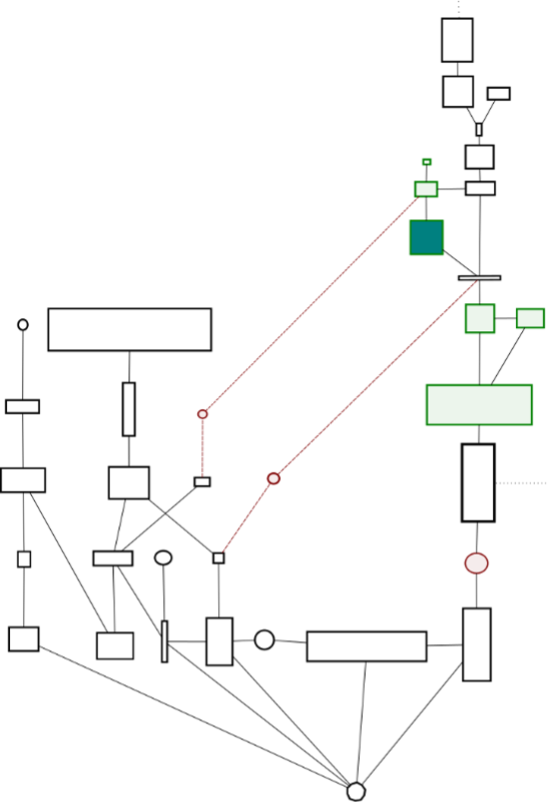

A three-step method was used to create the network to achieve the above-described objectives (Fig. 2). The dataset consists of two types of objects: spaces and persons. It also consists of two types of connections: undirected space to space and directed person to space relations. The dataset was imported to the open-source network analysis and visualization software Gephi, in which the network and the various visualizations were created.22

1) Spatial Network of the Royal Apartment

The first step is to create a network of connections between the different relevant spaces at the French court in 1585. These connections can be established by following the technique of access diagrams, where the enclosed spaces are represented as nodes, and the passageways between them are represented as edges. Since the method of access analysis usually departs their network from archeological remains or contemporary plans, I in this case, was able to choose to base the network on a contemporary ground plan of the royal apartment. Because Henri III was known to have resided most often in his Paris residence, the choice for Androuet du Cerceau’s plan of the royal apartment in the Louvre from 1576 seems sensible (Fig. 3).23

This plan, however, predates the 1585 ordinance. From contemporary descriptions, we furthermore learn that in connection to his newly established court regulations, Henri III had started to transform the spatial layout of his residences accordingly.24 The situation recorded by Androuet du Cerceau for the Louvre in 1576 was no longer in place in 1585.25 It is for this reason that instead of basing the spatial network on an existing ground plan, I decided to depart from the spatial layout as described in the ordinance itself.

From the second half of the sixteenth century, court ordinances started to make increasing provisions for the spatial requirements of the ruler’s lodgings, as was also the case for the 1585 ordinance. When it comes to the spaces required for his apartment, the King ordained that, if permitted by the architecture of the residence, his apartment needed to consist of at least five rooms: antechamber, state chamber (chambre d’Estat), audience chamber (chambre d’audience), chamber (chambre royalle), and at least one cabinet. Furthermore, the apartment needed to be laid out as much as possible on the same floor. Preferably the Queen’s chamber was directly accessible from the King’s cabinet. As stated in the ordinance, both Majesties would spend the night together in this first space.

In addition to her chamber, the Queen would also have a hall (salle), antechamber (antichambre), and a large cabinet. In turn, the Queen Mother’s apartment consisted of the same spaces as the Queen’s but did not have the requirement to be directly connected to that of the King. Ideally, it would, however, be situated on the same floor. Since both the Queen and the Queen Mother were provided with a hall, the King’s apartment probably included a similar space.

The different spaces (nodes) are connected based on the sequence and connections described in the ordinance to create the spatial network. The relation between the rooms is represented by undirect edges, indicating a two-way relationship between them (Fig. 4).

2) Reconstructing the King’s activities and whereabouts

A second step is reconstructing the King’s activities and whereabouts and incorporating this data into the spatial network. The 1585 ordinance provides extensive, but not always clear, information on the King’s activities and whereabouts during the week. Depending on the day of the week, Henri’s activities would change (Table 1). For this article, I decided to only reconstruct the King’s activities for a “regular” Monday at court.

| Time | Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5am | The king wakes up | The king wakes up | The king wakes up | The king wakes up | The king wakes up | The king wakes up | The king wakes up |

| 6am | Mass | Mass | Mass | Mass | Mass | Mass | Mass |

| 10am | Dinner | Dinner | Dinner | Dinner | Dinner | Dinner | Dinner |

| Council d'Estat de Sa Majesté | Audience | Audience for princes, cardinals, lords, etc. | Regular Audience | Audience for princes, cardinals, lords, etc. | Petitions | ||

| 2pm | The king retires | The king retires | The king retires | The king retires | The king retires | The king retires | The king retires |

| The king visits the Queen-Mother | The king visits the Queen-Mother | The king visits the Queen-Mother | The king visits the Queen-Mother | The king visits the Queen-Mother | The king visits the Queen-Mother | ||

| 3pm | The king plays 'jeu de mail' | The king goes hunting | The king goes horseriding | The king goes for a walk | The king plays 'jeu de mail' | The king goes for a walk | |

| 4pm | Vespers | Vespers | Vespers | Vespers | Vespers | Vespers | Vespers |

| 6pm | Soupper | Soupper | Soupper | Soupper | Soupper | Soupper | Soupper |

| 7pm | The king holds a ball | The king visits the Queen-Mother | The king visits the Queen-Mother | The king visits the Queen-Mother | The king holds a ball | The king visits the Queen-Mother | The king visits the Queen-Mother |

| 8pm | The king retires to go to sleep | The king retires to go to sleep | The king retires to go to sleep | The king retires to go to sleep | The king retires to go to sleep |

At 5 a.m., Henri’s lodgings were unlocked, and the King would wake up in the Queen’s chamber, assuming that they spent the night together. The King’s morning ritual, also known as the lever, started from that moment.26 It consisted of several steps: the King officially announcing he was awake, getting dressed in his cabinet, asking for his wine, entering the chambre royalle, and lastly, asking for his cloak and sword. At 6 a.m., the King heard Mass followed by his disner or midday meal in the King’s hall at ca. 10 a.m. After this meal, the King remained in the hall and seated at the table sheltered by a barrier held a ‘regular audience’. Afterward, he retired into his cabinet for amoment of solitude, and at 2 p.m., he visited the Queen Mother in her chamber. At 3 p.m., the visit ended, and the King went out to hunt, which was followed by Vespers, also known as evening prayer. At 6 p.m., the King enjoyed his soupper (evening meal) in the Queen Mother’s hall and an hour of relaxation in the Queen Mother’s apartment. At 8 p.m., Henri retired to his apartment, where the evening ritual or retiring ceremony known as the coucher took place. At 10 p.m., the King’s apartment was locked until 5 a.m. the following day.

To transfer this data to the network, an edge list was created of the directed relationship between the King's person and the used spaces. To include the temporality of these connections, temporal statements were defined and added to the edge list in the form of time sets which indicate the exact moment(s) that the space was in use by the King (Table 2). In the network visualization of the entire day, the thickness of the edges represents the number of temporal statements for which the King used this space (Fig. 5).

| Temporal statement | Time | Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 am | The doors of the king's lodgings are opened |

| 2 | 5 am | The king wakes up |

| 3 | The king has made known he had woken up | |

| 4 | The king asks for his wine | |

| 5 | The king's wine enters the 'cabinet' | |

| 6 | The king asks for his cloak and sword | |

| 7 | 6 am | The king goes to Mass |

| 8 | 10 am | The king has dinner |

| 9 | The king holds a regular audience | |

| 10 | The king retires after audience | |

| 11 | 2 pm | The king visits the Queen-Mother |

| 12 | 3 pm | The king goes hunting |

| 13 | 4 pm | The king goes to Vespers |

| 14 | 6 pm | The king has supper |

| 15 | 7 pm | The king goes to the Queen-Mother |

| 16 | 8 pm | The king retires to go to sleep |

| 17 | The king removes his cloak and sword and is given his nightdress | |

| 18 | The king goes to his cabinet | |

| 19 | The king removes his shoes | |

| 20 | The king retires into the cabinet to go to sleep | |

| 21 | 10 pm | The king's lodgings are closed |

From the network and the King’s schedule, three interesting insights emerge. First, according to the number of temporal statements, the space used most often by the king was his cabinet. Second, he did not actively use the antichambre and chambre d’audience, meaning that he only passed through them but did not stand in them. Third, apart from his own apartment, the King also spent considerable time in both the Queen Mother’s and, to a smaller degree, the Queen’s apartment.27

3) Reconstructing the courtiers’ access to the royal apartments

The degree of accessibility of the royal apartments was reconstructed following the rules of access stipulated for courtiers, an approach similar to step 2. An edge list was created by listing the different people or groups defined in the ordinance and when this person or group was allowed or required to be somewhere. Again, the edge list consists of directed person to space connections with timestamps indicating the temporal dimension of the relationship. The court ordinance sometimes refers to groups of courtiers having access to a space without specifying the number of people this group was part of. I have tried to overcome this shortcoming by taking their number from the ‘Officiers domestiques de la Maison du roi Henri III (1575-1589)’, which among others lists the number of people employed in the year 1585.28 This source, for example, allows us to identify the ‘ceux de la musicque de la chambre’ as consisting of 9 people

With the addition of the presence of (types of) courtiers in the spaces of the royal apartment, it has become possible to define the varying degrees of accessibility of these spaces with the use of in-degree centrality. In-degree is a count of the number of ties or edges directed to a node, which is the number of (types of) courtiers present in a space. A higher in-degree count corresponds to a higher degree of accessibility of the room.29

This number can be calculated separately or combined for the different temporal statements, thus representing the degree of accessibility based on the courtiers’ presence over the entire day (Table 3). By changing the node size to match the in-degree, this degree of accessibility can also be visualized (fig. 6). From the representation of the entire day, it becomes clear that the chambre d’audience followed by the chambre royalle and chambre d’Estat were the most used—and therefore probably most accessible—spaces in the King’s apartment.

| Space | Weighted In-Degree |

|---|---|

| King's Chambre d'Audience | 309 |

| King's Chambre Royalle | 288 |

| King's Chambre d'Estat | 232 |

| Queen-Mother's Antichambre | 77 |

| King's Cabinet | 46 |

| King's Antichambre | 44 |

| King's Salle | 38 |

| Queen-Mother's Cabinet | 35 |

| Queen-Mother's Salle | 14 |

The King’s antichambre seems less accessible for courtiers, but one needs to be careful with this interpretation. The ordonnance clearly states that to reach the ‘deeper’ rooms, such as the chambre d’estat and chambre d’audience, one must first pass through the king’s antichambre.30 Because courtiers would not stand in this room for a period of time, the graph does not accurately represent its accessibility. The same is the case for the salle, for which a high degree of accessibility can be deduced from the ordinance itself but not from the network representation.31 Unfortunately, it is impossible to overcome this inaccuracy by simply adding to the network the different in-degree counts together to represent this “passing through” spaces by courtiers.

The Spatiality of Privacy in the Royal Apartments

By combining the data of both the courtiers’ movements and those of the King in one network (Fig. 7), it is possible to make an abstract reconstruction of the spatiality of privacy at the court of Henri III. From the combined data concerning the entire day, it is clear that while, based on the courtiers’ movements, the chambre d’Estat, chambre d’audience, and chambre royalle know a high degree of accessibility—and could therefore be called a particularly public space of the royal apartment—the King on the contrary barely uses these spaces himself. Instead, he spends most of his time in his cabinet and the apartment of the Queen Mother. In turn, these spaces know a minimal degree of accessibility.

From this network, it is possible to better understand the spatiality of privacy in the royal apartment. The network visualizes how a high number of courtiers had access to the antichambre, chambre d’Estat, chambre d’audience and chambre royalle. While a high degree of accessibility can be witnessed for four cases, their accessibility does gradually decrease according to the “deepness” of the space in question.However, the significant difference in accessibility between the chambre royalle and the King’s cabinet demonstrates how this gradual change in accessibility is not linear. The degree of privacy abruptly increases on the threshold of the King’s cabinet, and for this reason, I would argue that the spatial boundary of privacy at the King’s apartment is located at this threshold.

While privacy at the French court is sometimes believed to have been limited or non-existent, this network shows that this is not the case. At the same time, we cannot deny that the King’s apartment was, for the most part, a public and accessible space. At first glance, this might seem contradictory. However, with the reconstruction of the King’s movements during the day, the King’s choice to use the less accessible spaces is witnessed and, from this, he experienced a form of privacy. At the same time, however, the King maintained his public apartment as an important characteristic of the French court. I would thus argue that while it is true that in France, the King’s apartment was, for the most part, a relatively accessible space, the King himself, as a result of his use of space, was not similarly accessible as a person. This will become even more clear when temporality is taken into account.

The Effect of Temporality

Thus far, this network has reconstructed the spatiality of privacy in the course of an ideal Monday at the court of Henri III of France. However, the effect of temporality on the degree of accessibility and the spatiality of privacy cannot be ignored. Since the King’s activities changed during the week, it is possible that accessibility and privacy changed accordingly. Comparing the different days of the week is out of scope for this article, but by including the temporal statements in the network, the data for different times of the day can be compared.

The importance of temporality on the degree of accessibility is already clear from the 1585 ordinance. It is, for instance, stated that between 10 p.m. and 5 a.m., the King’s apartment was closed off for all courtiers, except for the valet de chambre who was sleeping in the King’s chamber.32 Thus, at that time, the earlier defined spatial boundary was not situated between the chambre royalle and the cabinet, but instead lay at the entrance of the King’s apartment.

From 5 a.m., some courtiers were allowed entrance to the King’s apartment. Until Henri had officially announced he was awake, their presence was restricted to the chambre d’Estat and chambre d’audience (see time slices 1-2, Fig. 8). The spatial boundary of privacy then thus lay between the chambre d’audience and chambre royalle. After officially announcing the King’s awakening, other courtiers were able to enter the rooms of the King’s apartment in different steps (time slices 3-5, Fig. 8). It is then that more courtiers were allowed to enter the chambre royalle and that the spatial boundary of privacy switched to the entrance of the cabinet. This movement was reversed during the retiring ceremony at night (time slices 16-19, Fig. 8).

When Henri left his apartment to go to Mass until he retired for the night in his cabinet, the same accessibility is observed as when the King entered the chambre royalle in the morning to ask for his cloak and sword (time slice 6, Fig. 8).33 The big difference, however, is that during this time, the King himself was not present in the apartment. The only exception is when he returned from his public dinner and audience in the hall and retires to his apartment at 2 p.m. (temporal statement 10). Then access to the King’s apartment becomes much stricter and only a select group of courtiers is allowed entrance to the chambre royalle (time slice 10, Fig. 8).

The comparison of these time slices demonstrates the effect of temporality on the degree of accessibility in the King’s apartment. Furthermore, temporality affected to some degree also the spatiality of privacy with its spatial border shifting from the entrance of the King’s apartment to the doors of the chambre royalle and cabinet. During the day, however, this spatial boundary remained unchanged with its situation between the chambre royalle and cabinet. Only with the start of Henri’s retiring ceremony, this boundary shifted back to the entrance of the apartment.

Conclusion

In this article, I have demonstrated how the concept of access diagrams in combination with additional source material(s), like court ordinances, can be used to define and—to a certain degree—measure accessibility and the spatiality of privacy. Because access diagrams are mainly concerned with the positioning and relationships of enclosed spaces, they lack important information provided by the inclusion of humans as actors and temporality as an important variable. The method developed in this article has overcome these limitations.

While we cannot—and should not—pretend that networks allow for a perfect reconstruction of reality, especially in the case of the normative court ordinances and the slippery concept that is privacy, the creation of the network does provide for a better understanding of the source material. From this visualization and the possibility of quantification, it has become possible to test and formulate theories on accessibility and the spatiality of privacy at court. Acknowledging the method’s usefulness as a research tool it is not only through the network, but from the continuous dialogue between the digital and traditional research methods that new insights from the source material are acquired.

Bibliography

Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition. University of Chicago Press, 1958.

Bastian, Matthieu, and Heymann, Sebastian, and Jacomy, Mathieu. “Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks.” Paper presented at International AAAI onference on Weblogs and Social Media, 2009. https://gephi.org/users/publications/.

Benoist, Luc. Histoire de Versailles. Presses Universitaires de France, 1973.

Chaline, Olivier. “The Kingdoms of France and Navarre. The Valois and Bourbon Courts c. 1515-1750.” In The Princely Courts of Europe 1500-1750, edited by John Adamson. Seven Dials, 2000.

Chatenet, Monique. “Henri III et ‘l’ordre de la cour’. Évolution de l’étiquette à travers les règlements généraux de 1578 et 1585”. In Henri III et son temps: actes du colloque international du Centre de la Renaissance de Tours, octobre 1989. Librarie Philosophique J. Vrin, 1992.

Chatenet, Monique. La cour de France au XVIe siècle. Vie sociale et architecture. Picard, 2002.

De Jonge, Krista. “Hofordnungen als Quellen der Residenzenforschung? Adlige und herzogliche Residenzen in den südlichen Niederlanden in der Burgunderzeit.” In Höfe und Hofordnungen. 5. Symposium der Residenzen-Kommission der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, Sigmaringen, 5. Bis 8. Oktober 1996. Jan Thorbecke Verlag, 1999.

Fairclough, Graham. “Meaningful constructions – spatial and functional analysis of medieval buildings.” Antiquity 66 (1992): 348-366.

Foster, Sally M. “Analysis of Spatial Patterns in Buildings (access analysis) as an insight into a social structure examples from the Scottish Atlantic Iron Age.” Antiquity 63 (1989): 40-50.

Friedman, Alice T. House and Household in Elizabethan England: Wollaton Hall and the Willoughby Family. University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Girouard, Mark. Life in the English Country House. A Social and Architectural History. Yale University Press, 1978.

Hillier, Bill, and Hanson, Julienne. The Social Logic of Space. Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Orlin, Lena Cowen. Locating Privacy in Tudor London. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Paravicini, Werner. “Europäische Hofordnungen als Gattung und Quelle.”In In Höfe und Hofordnungen. 5. Symposium der Residenzen-Kommission der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, Sigmaringen, 5. Bis 8. Oktober 1996. Jan Thorbecke Verlag, 1999.

Ronnes, Hanneke. “An Archaeology of the Noble House. The Spatial Organisation of Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Castles and Country Houses in the Low Countries and the Privacy Debate.” Medieval and Modern Matters 3 (2012): 135-163.

Sherlock, Rory. “Changing Perceptions: Spatial Analysis and the Study of the Irish Tower House.” Château Gaillard 24 (2010): 239-250.

Thurley, Simon. The Royal Palaces of Tudor England: Architecture and Court Life, 1460-1547. Yale University Press, 1993.

Williams, Neville. ‘The Tudors. Three contrasts in personality’. in The Courts of Europe: politics, patronage, and royalty 1400-1800, edited by A.G. Dickens, 147-168. London: Thames and Hudson, 1977.

Notes

-

This article is the result of my research within the PALAMUSTO European Training Network. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 861426. This article reflects only the author’s views, and the Agency is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. The dataset created for this article is available in Zenodo: 10.5281/zenodo.14244039. ↩

-

Chatenet, “Henri III et ‘l’ordre de la cour,’” 133 ↩

-

Louis XIV stated in his Mémoires the following: “Il y a des nations où la majesté des rois consiste... à ne point de laisser voir; et cela peut avoir ses raisons parmi les esprits accoutumés à la souvitude, qu'on ne gouverne que par la crainte et la terreur. Mais ce n'est pas le génie de nos Français, et ... s'il y a quelque caractère singulier dans cette monarchie, c'est l'accès libre et facile des sujets au prince.” Cited by Benoist, Versailles, 29. ↩

-

Neville Williams, in comparing the royal English court with the French royal court states that ‘Unlike France, where the Valois and Bourbon kings lived out almost their whole lives before their courtiers’ gaze, public and private spheres in the English palaces were clearly demarcated.’ See: Williams, The Tudors, 108. ↩

-

Orlin, Locating Privacy, 1. ↩

-

See among others: Girouard, Life in English Country House, 11; Friedman, House and Household, 179; Thurley, Royal Palaces, 37. ↩

-

Orlin, Locating Privacy, 108-111 ↩

-

Arendt, The Human Condition, 1958. ↩

-

1562, Michele Soriano, published by Alberi 1839-1863, IV, p. 123-124: ‘(…) it arises that the king of France is so domestic with his subjects that he has them all as companions and no one is ever excluded from his presence, so much so that even the lackeys, very vile people, have the audacity to want to enter the king’s intimate chamber.’ ↩

-

Paris, Archives Nationales, KK 544, fol. 1r-7r. The dating of this letter is debated, however, I have chosen to follow the dating provided by J. H. Mariéjol in: Mariéjol, Catherine de Médicis, 270. ↩

-

Chatenet, Cour de France au XVIe siècle, 136. ↩

-

Hillier and Hanson, Social Logic of Space. See also Foster, “Analysis of Spatial Patterns in Buildings,” 40. ↩

-

Examples of the application of access diagrams in archaeology are: Fairclough, “Meaningful constructions”; Foster, “Analysis of Spatial Patterns in Buildings”; Sherlock, “Changing Perceptions.” ↩

-

Ronnes, “Archeology of the Noble House,” 144. What the authoractually means with “not straightforward” is not explained, but isprobably related to the knowledge and tools required to construct anaccess diagram. ↩

-

The original theory of Hillier and Hanson included a metricalanalysis, in which the “depth” of a particular space was measured. Deep spaces are “spaces which are reached from the entrance only by passing through a relatively large number of other spaces on the way” and are generally considered to be more “private” than “shallow” or “undeep” spaces. See Sherlock, “Changing Perceptions,”241. ↩

-

Ronnes, “Archeology of the Noble House,” 143. ↩

-

Chaline, “Kingdoms of France and Navarre,” 88. ↩

-

For the purpose of this article, I used the transcriptions provided by the Centre de recherche du château de Versailles as part of the project “L’étiquette à la cour: textes normatifs et usages” (2014-2016), https://chateauversailles-recherche.fr/francais/ressources-documentaires/corpus-electroniques/corpus-raisonnes/l-etiquette-a-la-cour-de-france/reglements-de-la-maison-du-roi.html. For the original document: Paris, Archives nationales, KK 544 fol. 55r – 141r. For more about Henri III’s court ordinances, see: Chatenet, “Henri III et ‘L’ordre de la cour’”. ↩

-

Paravicini, “Europäische Hofordnungen,” 14. ↩

-

Paravicini, “Europäische Hofordnungen,” 17. ↩

-

De Jonge, “Hofordnungen als Quellen,” 176. ↩

-

See: Bastian, Heymann, and Jacomy, “Gephi.” See also: https://gephi.org/. ↩

-

Chatenet, Cour de France au XVIe siècle, 37. ↩

-

Chatenet, Cour de France au XVIe siècle, 182. ↩

-

Chatenet, Cour de France au XVIe siècle, 182. ↩

-

It was quite common in the early modern period for rulers and other noblemen to be assisted by responsible courtiers after waking up and while dressing. Nevertheless, at most European courts this was not a ‘public’ events where other courtiers were allowed to enter the rulers chamber and witness the dressing ritual taking place. As we learn from the letter of Catherine de’ Medici to her son Charles IX, this public aspect of the rising ritual where princes, lords, captains, knight of the order, gentlemen of thechamber, gentleman servants and the maître d’hôtel were allowed to join the King in his chamber while he was putting on his shirt, wasin place in the time of Henri II of France. During the reign ofLouis XIV this rising ritual was even more formalised and divided between a Grand Lever and Petit Lever. For the letter of Catherine de’ Medici to Charles IX of France see: Paris, ArchivesNationales, KK 544 fol. 1r-7r; or: https://chateauversailles-recherche.fr/francais/ressources-documentaires/corpus-electroniques/corpus-raisonnes/l-etiquette-a-la-cour-de-france/reglements-de-la-maison-du-roi.html.For more about the ceremony of the lever at the sixteenth-centuryFrench court see Chatenet, Cour de France au XVIe siècle, 114-5. ↩

-

The 1585 court ordinance does not provide detailed information on the Queen and Queen Mother’s whereabouts during the day, except for when they concern the King. ↩

-

BnF, Ms. Fr. 7854, Officiers des maisons des roys, reynes, etc. depuis Saint Louis jusqu’à Louis XIV, III, 167v. ↩

-

Note that because we are not sure about the exact number of courtiers, we can only say something about the degree of accessibility based on the different groups of courtiers that were allowed to enter the space. It however does not give us a count of the exact number of people present in the space. ↩

-

“Tous lesquels passeront pour entrer dans ladicte chambre d’audience par la salle, antichambre et chambre d’Estat de Sa Majesté” to reach the chambre d’audience [Fol. 130v]. ↩

-

The high degree of accesibility can be deduced from the following: “Et en la salle, depuis le matin que l’on sera entré au logis de Sa Majesté jusques au soir que les portes dudict logis se fermeront, touttes sortes personnes y pouront entrer, […], ” [fol. 132r]. ↩

-

“Que ledict cappitaine qui sera en quartier assiste tous les soirs à la closture des portes du logis de Sa Majesté que se fera précisément à dix heures, soit en esté ou en hiver, après toutefois avoir faict trois crys l’un après l’aultre par la cour pour advertir un chacun de se retirer, sans que pour qui ce soit, si Sa Majesté ne le commande, elle soit tenue ouverte plus tard, ny ne s’ouvrira après ladicte heure. Il se trouverra aussy le matin à l’ouverture de ladicte porte, qui se fera à cinq heures du matin ou plus tost sy Sa Majesté est esveillé, et nul n’y entrera auparavant.” [fol. 97 r-v] ↩

-

“Depuis que Sa Majesté aura faict dire qu’elle est éveillée iusques à ce qu’elle soit retirée dans son cabinet pour s’aller coucher, les princes, cardinaux, seigneurs et gentilhommes pourront demeure raux chambres de Sa Majesté s’ils veullent, ausquelles il est permis d’entrer depuis que Sa Majesté afaict demander son espée et sa cappe le matin, excepté depuisqu’elle se sera retirée l’après-dinée en son cabinet, iusques à deux heures après midy, que alors nul ne demeurera en la chambre royalle, oultre les valets de chambre couchant en icelle, huissiers de ladicte chambre royalle et valetz de chambre qui seront en leur jour, que les princes, ducs, officiers de la couronne, grand maistre de l’artillerie, ceulx des affaires de Sa Majesté, le cappitaine des gardes servant le quartier, le premier escuier, le grand maistre des cérémonies ou en son absence celuy qui tiendra son lieu s’ilz veullent et aussy les neuf gentilhommes de la chambre qui particullièrement seront en leur iour de service, et les cinq gentilhommes ordinaires du roy en semaine. “ [fol. 137v – 138r] ↩

Author

Miara Fraikin,

KU Leuven, miara.fraikin@kuleuven.be,