Private Birth, Public Authority: Topic Changes from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century in German Midwifery Books

Abstract

Discourses on midwifery changed gradually but also significantly from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century across Europe. In German-speaking territories, texts in the vernacular managed to reach a whole new audience, creating an adjacent market to the Latin learned instructions on pregnancy and childbirth at the turn of the sixteenth century.1 Manuals for midwives and instructions to pregnant women spread much wider as printing became more accessible, making the turn to the sixteenth century a heyday of influential midwifery manuals.2 As this knowledge circulated broadly, organizing and regulating the practice of midwifery became an increasing concern for the authorities. In response, many German cities began to issue ordinances for the local midwives.3 The seventeenth century witnessed the reprint of many of these manuals, as well as the translations of popular guides from different European regions.4 In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, faculties of medicine embraced the duty of examining midwives at an official level. That meant that new instructional texts were issued, and ordinances in many cases included the need for licenses by medical authorities in order for a midwife to be able to practice.5 In her study of southern Germany, Merry E. Wiesner has pointed out that such a shift seems to be connected to the growing public/private split and a consistent “privatization” of women.6 This “privatization” meant that the early modern period saw an increase push for women to be relegated to the domestic realm, with a more explicit association of the male as public and the female as private. However, she concludes that midwifery is a point of tension in such discourse. Female midwives worked as a bridge in the public/private distinction: they operated in intimate contact with the pregnant women while having a significant public role. When most women had their responsibilities attached to their households, midwives could even hold office in the principalities. However, the eighteenth-century growth in male midwives broke the female-dominant knowledge domain and demanded closer supervision of their practice of female midwifes, in a way removing their access to public authority. This notion of “privatization” of women and female midwives’ exclusion from their position of authority as a process from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century helps us understand how birth went from a social moment with an intimate bond between the birthing person and the practitioner assisting to a more private and medicalized procedure.

Developments in the literature on midwifery directly impacted medical discourse and the creation of the field of obstetrics. Tracing the legal, medical, and economic influences in this literature through this longue-durée history – from the early vernacular publications to the efforts of officializing and medicalizing the profession – can help us understand the circulation of knowledge on pregnancy and childbirth. Distant reading can be a great help in such an endeavor. Applying topic modeling tools to explore the different topic trends in midwifery publications can provide an important overview of the shifts in perceptions surrounding midwives’ practices and knowledge. My aim is to create a control group to examine the benefits and pitfalls of such an approach. I will select some key midwifery publications of the sixteenth and eighteenth century that are machine-readable and available online and run them through the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model provided by the tool MALLET. I will separate this corpus into different assessment groups and compare the results delivered with a human examination of the sources. The results presented here can inform future research questions that can involve much larger corpora and help us trace the movement of early modern midwifery in the private/public spectrum in a long-durée perspective.

Establishing a control corpus and topic modeling

The idea of the corpus used here is to have selected relevant publications of midwife manuals and ordinances from the sixteenth century and from the eighteenth century to observe how the topic modeling tool performs in terms of tracing the discourse trends of these two defining periods in midwifery literature in Germany. These texts were all collected from available online repositories that can be accessed via Google Books,7 as the optical character recognition results of these copies present the same patterns and issues when it comes to the German Fraktur typeface in which these texts were printed.8

There are some field-defining texts when we speak of early modern German midwife manuals. The work of Eucharius Rößlin (c. 1470 – 1526) is on this list. His Der schwangeren Frauen und Hebammen Rosengarten is considered the first comprehensive midwifery manual in the German vernacular, published in 1513 Strasbourg.9 This text was, hence, the starting point of forming the present corpus. But midwifery literature includes more than manuals – there was spiritual guidance to be provided, and books of prayers for pregnant women were part of midwives’ repertoire. These books provided spiritual guidance and religious explanations for the experiences of pain, illness, and death related to childbirth. Given the high mortality rate for pregnant women and infants, this particular kind of consolation literature was considered crucial for midwives to operate as healers of body and soul.10 Moreover, ordinances defined the contours of their practices’ legality, most times being written with the help of official midwives. As such, they are a crucial source for understanding what was considered the proper practice of midwifery, what knowledge and techniques could be employed, and their responsibilities to their patients.

The literature on midwifery is, therefore, varied and composed in different styles. Ordinances were written following typical codes of regulations. Spiritual guidance books follow a more theological formulation. Manuals were composed to provide short yet precise descriptions of procedures, techniques, and potential effects on the patients’ bodies, sometimes including illustrations. These variations in writing style can have an effect on the results of the topic modeling tools. As such, the corpora were created with these differences in mind. For the sixteenth-century corpus, eight books were included, of which two were spiritual guidance, two were ordinances, and four were manuals.11 The same was done for the eighteenth century – the corpus was composed of eight books, of which two were spiritual guidance, two ordinances, and the remaining were manuals.12 The two corpora will be analyzed separately to contrast the topics that emerge in these two pivotal moments. These texts create a balanced sample, as their OCR is of the same standard, they are available open access for the reproduction of the study and encompass all the main kinds of printed sources for the study of midwifery. As an initial group, they will allow us to see what main hurdles future studies might face when incorporating big data for historical sources that include German Fraktur texts.

To extract topics from this corpus, I used the MALLET toolkit. The initial attempts made clear that these historical German texts required a custom stopword list. MALLET has standard lists of stopwords is in English, German, Finnish, French, and Japanese, but the pre-made list in German does not account for common historical variations (such as vnnd instead of und).13 Some stopwords are also affected by OCR problems with the historical German spelling (for instance, uns can be spelled as unß, and the OCR can read it as unl3 or similar). Moreover, common OCR misidentifications had to be taken into account (for instance, for the stopword solche, it was crucial to add also ſolche, and folche, as well as the conjugated versions like solchen or solches, for example, in all of the variations of potential OCR misrecognition). This also required particular care not to remove potential useful words. Using the example above of the ‘s’ being recognized as ‘f’, for the stopword sein (to be, or his, or [we] are) it was needed to add ſein and ſeyn, but fein is its own word (fine, subtle, or delicate). We need to be aware, then, if the topic fein appears, it might just be a misidentified sein. The consistency of misreading of certain letters can be used to refine future OCR scans. The list developed and used here will be available at GitHub to be used and expanded for future experimentation with German Fraktur sources.14 Taking these issues into account, I ran a few experiments on topic modeling this midwifery literature.

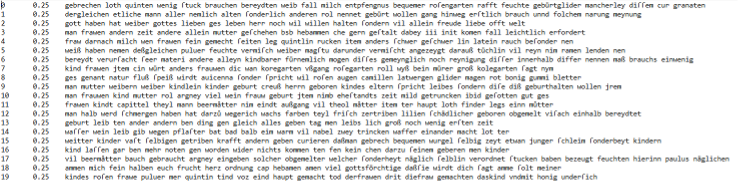

Sixteenth-century topics

The topics of the sixteenth-century corpus reveal patterns of problems with the OCR. The letter ‘z’ is consistently substituted by the letter g’, as in the words for remedy (Arznei) appears as argney, and root (Wurzel) shows up as wurgel. Some of the topics are also beginnings or endings of words that have been separated in the pages of the book (like ges or nen). As such, depending on the corpus and the goal of a particular study, such separated endings could be added to a custom stopword list.

Most of the topics are expected terms relating to midwifery, such as woman/women (fraw/frawe/frawen), female (weib/weibern), child (kind/kindlein), mother (mutter), pregnancy (schwanger), and birth (geburt/geboren). Rosengarten is another prominent topic. Although that attests to the popularity of Rößlin’s book, one of the reasons is that Ehestandts Artzeney also includes a copy of the Rosengarten. On top of that, most manuals reference this work, and it became basically a marketing strategy to include the term Rosengarten as a part of midwifery texts, . with the association with the ‘rose garden’ also appearing in translation across Europe. 15

Body (leib), uterus (bärmütter – appearing as beermåtter), navel (nabel), eyes (augen), back (rucken) and adjectives like moist (feucht), heavy (schwer) and warm (warm), and pain (schmerzen – appearing as ſchmergen) indicate key physical aspects in the texts. The topics also highlight medicines such as powders (pulver), plasters (pflaster), substances like chamomille (camillen), leafs (bletter), lilies (lillien), honey (honig), and liquids like water (wasser) and milk (milch), which occur in the texts as recipe ingredients, but also referring to mother’s milk and amniotic fluid. Herbal remedies were an extensive part of midwives’ treatment repertoires. The sixteenth century witnessed a renewed interest in the pharmacological use of plants. However, these medicines, just like midwifery, had to be used in a controlled manner, removing superstitious folk practices from the use of plants. Rößlin’s Rosengarten also provided a lot of information on the preparation of salves and ointments to alleviate the pregnant person’s pain and ailments.16 An intriguing topic is the appearance of gummi – which would normally be translated as rubber. While rubber originated from Hevea brasiliensis as we know it today was not a substance used in sixteenth-century German-speaking territories, by reading the sources, it is clear that the texts are referring to different natural latex, such as the ones derived from Asafoetida or Ferula persica, which were used as bonding agents for early modern pills. Indeed, following such topics in the corpus indicated that the said gummy substance was extracted from asafoetida— referred to as Teuffels kott in sixteenth-century German. 17 Local midwives, usually from a peasant background, would have a harder time coming across asafoetida, which highlights that sixteenth-century midwifery books already aimed at approximating the midwives’ practices to official medicine and apothecary remedies. Situating the herbal medicines used by midwives closer to the practice of the apothecaries rather than their folk use of plants also aligns with Wiesner’s point that, although women could not be excluded from midwifery as they could from other medical practices, they still could be placed under the scrutiny and be subjugated to the knowledge of male scholarship. 18

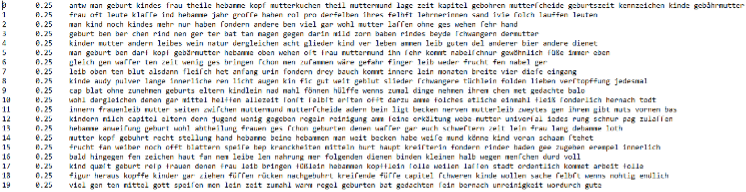

Eighteenth-century topics

There are a lot of parallels between the topics from the sixteenth-century and the eighteenth-century corpora. Frau/frauen, kind/kinder, mutter, schwangern, as expected, continue to feature as key topics. Birth (geburt) appears also with further specifications, such as time of birth (geburtszeit) and afterbirth (nachgeburt). We can notice the linguistic change of uterus from Bärmütter to Gebärmütter, as it is known in modern German.

There are a lot of parallels between the topics from the sixteenth-century and the eighteenth-century corpora. Frau/frauen, kind/kinder, mutter, schwangern, as expected, continue to feature as key topics. We can notice the linguistic change of uterus from Bärmütter to Gebärmütter, as it is known in modern German.

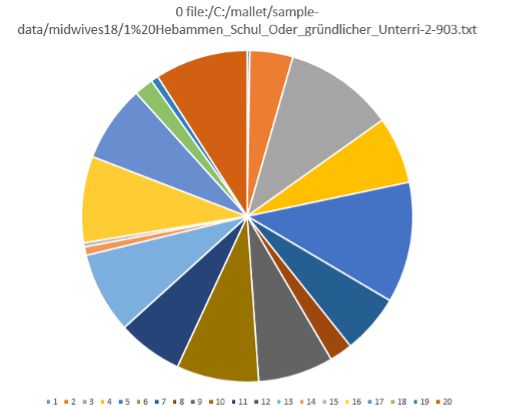

One of the main turns on the topics can be found in group 1 (see figure 2). Grouped there are topics like klasse (class) and lehrnerinnen (‘trainee’ in the feminine), which might indicate the increasing pressure for midwives to engage in anatomical lessons. This prominence of education terms could be influenced by the book Hebammen-Schul Oder gründlicher Unterricht (“Midwives’ School or Most Thorough Lesson”) and its use of educational analogies. By looking at the text composition, however, group 2 is not significantly represented for that particular text (See figrue 3).

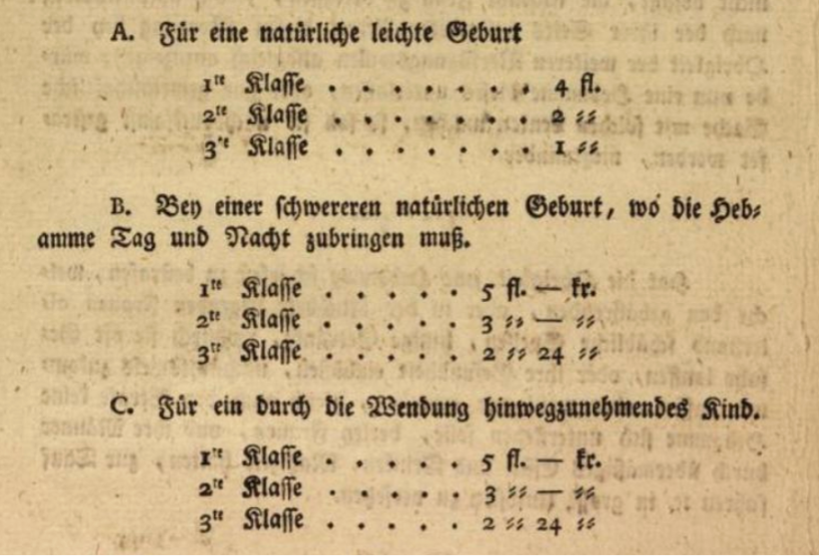

In fact, when locating those clusters, they point mostly towards the selected eighteenth-century ordinances. Although Klasse can be related to education, the term has multiple meanings. In this case, looking closer at the corpus, the ‘class’ does not refer to the learning environment, but it is a division of the different ‘classes’ of pregnant women that the midwives would treat and how much they were allowed to charge each of the groups. As midwifery became more and more professionalized, the monetization of the practice also became more institutionalized.

Another important topic is urine (urin). This could indicate that uroscopy was a relevant form of diagnosis in eighteenth-century midwifery. Uroscopy was already one of the main forms of diagnosis in formal medicine in the medieval period. Being an almost ubiquitous practice in the sixteenth century, examining a patient’s urine seemed to have lost its appeal as a medical skill by the seventeenth century, as doctors sought novel forms of diagnosis.19 This appearance in eighteenth-century midwifery manuals might point out two potential developments. Although uroscopy might not have been a trend among doctors, it could have been seen as an important basic tool for midwives undergoing medical lessons to have under their belt. On the other hand, eighteenth-century technical developments renewed the interest in analyzing urine, bringing it again to the forefront of tools for diagnosis.20 This continuity in practices also aligns with Wiesner’s observation of how little the actual obstetrician practices changed across these centuries. 21

Conclusion

Topic modeling can be a wonderful tool to explore discourse changes across time, as the project Mining the Dispatch has proved.22 A simple experiment with this control corpus from crucial periods for midwifery literature already indicates some subtle but significant shifts. Tools like MALLET can operate independently of the corpus’ language, which lends itself perfectly to exploring Wiesner’s notion that developments in the public/private divide are crucial to understanding the professionalization of midwifery and the establishment of obstetrics. Nevertheless, language still imposes challenges for a study with larger corpora. OCR problems deriving particularly from German Fraktur sources are at the center of most of these issues. This experiment has already identified some useful patterns that are usually caught as topics – information that can be used to fix such issues on a larger scale. The consistency of misreading of certain letters can be used to refine future OCR scans. The particularities of German historical materials also require a customized list of stopwords. The list developed and used here will be available at GitHub to be used and expanded for future experimentation with German Fraktur sources. Moreover, page headings must be taken into account within the corpus, as they can skew results. Those are simple hurdles to overcome, and using topic modeling tools to follow patterns in discourse change in midwifery literature can be invaluable for understanding women’s birthing practices and their professionalization, privatization, and even marginalization across the centuries.

Acknowledgement:

I would like to thank the editors of this special issue, Natália da Silva Perez and Sanne Maekelberg, for their important comments and the anonymous peer reviewers for their suggestions and input. This work was only possible thanks to the support of the Centre for Privacy Studies (DNRF138) and the Swedish Research Council project Secrets to Patents.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Deventer, Hendrik van. Neues Hebammen-Licht: in welchem aufrichtig gelehret wird, wie alle unrecht liegende Kinder, lebendige oder todte, blos mit den Händen in ihr rechtes Lager zu bringen, und glücklich heraus zu ziehen, welches die vielen Kupffer deutlich vor Augen stellen; Alles aus eigener Erfahrung von dem Herrn Autore erfunden, den teutschen Chirurgis und Hebammen zum Besten aus dem Lateinischen ins Deutsche übersetzt. Cröker, 1740.

Günther, Thomas. Ein Trostbüchlein für die Schwangern vnd Geberenden Weiber: wie sich dise für, inn, vnd nach der Geburt, mit Betten, Dancken, vnd anderm, Christlichen verhalten sollen; Dergleichen zuuor in Truck nie außgangen. Frankfurt: Feyerabend und Hüter, 1564.

Gutermann, Georg Friederich. Erklärte Anatomie für Hebammen, samt derselben Nutzanwendung zur Praxis. Augsburg: Mertz und Mayer, 1752.

Hugo, Johann. Tröstlicher Bericht für schwangere Frauen. Frankfurt: Feyerabent und Hüter, 1563.

Jördens, Johann Heinrich. Selbstbelehrung für Hebammen, Schwangare und Mütter. Berlin: Buchhandlung des Geh. Commerzien-Raths Pauli, 1797.

Katzenberger, Leonhard Jakob. J. Katzenbergers Hebammen-Catechismus: hauptsächlich zum Gebrauch für Wundärzte und Hebammen auf dem Lande. Münster: Ph. H. Perrenon, 1778.

Lonitzer, Adam. Hebam[m]enbüchlin Empfengnus un[d] Geburt der Menschen, Auch Schwangerer frawen allerhand züfellige gebrechen und derselben Cur und Wartung; item von der jungen Kindlin Pflege, Aufferziehung, und derselben mancherlei Schwacheyten. Frankfurt, 1572.

Lonitzer, Adam. Reformation, oder Ordnung für die HebAmmen: Allen guten Policeyen dienstlich. In verlegung Doct. Adami Loniceri, M. Joannis Cnipii vnnd Pauli Steinmeyers, 1573.

Ordnung einer Erbarn Raths der statt Regenspurg die Hebammen betreffende. Kohl, 1550.

Ordnung Für Die Hebammen in München: Dd. 12. Nov. 1791.

Rößlin, Eucharius. Der Swangern Frauwen vnd Hebammen Rosengarten. Straßburg: Flach, 1513.

Rößlin, Eucharius. Ehestandts Artzney: Schwangerer Frauwen und HebAmmen Rosengarten Doct. Eucharii Rößlin, weilandt Stattartzt zu Franckfurt. Frauwen Artzney, D. Johan Cuba. Die Heimligkeiten Alberti Magni. Von sörglichen zufellen der schwangern Frauwen, Ludovicus Bonatiolus. Kindspflegung, D. Barth. Merlinger. Frankfurt: Rab und Han, 1565.

Ryff, Walther Hermann. Frawen Rosengarten. Von vilfaltigen sorglichen Zufällen vnd gebrechen der Mütter vnd Kinder, So jnen vor, inn, vnnd nach der Geburt begegnen mögenn … New ann tag geben, Durch Gwaltherum Reiff. Frankfurt: Bei Christian Egenolff, 1545.

Sommer, Johann Georg. Hebammen-Schul Oder Gründlicher Unterricht, Wie Eine Hebamme Gegen Schwangere, Kreistende Und Entbundene Weiber Und Deren Kinderlein, so Wohl Bey Natürlichen Als Unnatürlichen Geburten, Sich Zu Verhalten: Nebenst Einem Nützlichen Weiber- Und Kinder-Pfleg-Büchlein Und Einer Treuen Anführung, Wie Den Meisten Kinder-Kranckheiten Zu Begegnen: Wie Auch Einer Anleitung Zur Christlichen Kinder-Zucht. Coburg, 1715.

Verneuerte und vermehrte Brandenburgische Hebammen-Ordnung, des Fürstenthums Burggraffthums Nürnberg unterhalb Gebürgs: den 29. April Anno 1743. Messerer, 1743.

Widenman, Barbara. Kurtze, Jedoch Hinlängliche Und Gründliche Anweisung Christlicher Hebammen Nebst Einem Anhang, Wie Eine Zu Diesem Beruff Sich Angebende Hebamme Obrigkeitlich Zu Examiniren. Augsburg, 1735.

Secondary Literature

Amberg, Silke. Hebammenordnungen in deutschen Städten um 1500. Norderstedt: GRIN Verlag, 2010.

Baldassarri, Fabrizio, ed. Plants in 16th and 17th Century: Botany between Medicine and Science. Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110739930-202

Green, Monica H. “The Sources of Eucharius Rösslin’s ‘Rosegarden for Pregnant Women and Midwives’ (1513).” Medical History 53, no. 2 (April 2009): 167–92.

Hobby, Elaine, ed. The Birth of Mankind: Otherwise Named, The Woman’s Book. Literary and Scientific Cultures of Early Modernity. Farnham, England: Ashgate, 2009.

Jones, Edgar. “Google Books as a General Research Collection.” Library Resources & Technical Services 54, no. 2 (April 1, 2010): 77–89. https://doi.org/10.5860/lrts.54n2.77.

Kruse, Britta-Juliane. Verborgene Heilkünste: Geschichte der Frauenmedizin im Spätmittelalter. Quellen und Forschungen zur Literatur- und Kulturgeschichte 5. Berlin; New York: W. de Gruyter, 1996.

Springmann, Uwe, and et al. “Ground Truth for Training OCR Engines on Historical Documents in German Fraktur and Early Modern Latin.” JLCL 33, no. 1 (2018): 1–19.

Vetulani, Zygmunt, Patrick Paroubek, and Marek Kubis, eds. Human Language Technology. Challenges for Computer Science and Linguistics: 8th Language and Technology Conference, LTC 2017, Poznań, Poland, November 17–19, 2017, Revised Selected Papers. Vol. 12598. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66527-2.

Wiesner, Merry E. “The midwives of south Germany and the public/private dichotomy.” In The Art of Midwifery: Early Modern Midwives in Europe, edited by Hilary Marland, 77–94. London; New York: Routledge, 1993.

Endnotes

-

Green, “The Sources of Eucharius Rösslin’s ‘Rosegarden for Pregnant Women and Midwives’ (1513)”, 167–92. ↩

-

Kruse, Verborgene Heilkünste, 9. ↩

-

Amberg, Hebammenordnungen in deutschen Städten um 1500 , 3. ↩

-

One of the most popular midwifery manual in seventeenth-century was the translation of the midwifery writings of Louise Bourgeois, who became the French royal midwife in 1601. ↩

-

Midwife examinations already existed in the sixteenth century, but it is in the eighteenth century that consistent official efforts were put in place to demand licenses for the practice of midwifery. ↩

-

Wiesner, “The midwives of south Germany and the public/private dichotomy” , 77. ↩

-

For more information on the Google Books digitization and OCR initiatives, see Jones, “Google Books as a General Research Collection,” 77–89. ↩

-

Fraktur prints are notorious for the type of errors produced in the OCR process. See Uwe Springmann and et al., “Ground Truth for Training OCR Engines on Historical Documents in German Fraktur and Early Modern Latin,” JLCL 33, no. 1 (2018): 1–19 and Mika Koistinen “How to Improve Optical Character Recognition of Historical Finnish Newspapers Using Open Source Tesseract OCR Engine – Final Notes on Development and Evaluation” in Vetulani, Paroubek, and Kubis, eds., Human Language Technology, 17–30. ↩

-

Green,”The Sources of Eucharius Rösslin’s ‘Rosegarden for Pregnant Women and Midwives’ (1513),” 167–92. ↩

-

Lahtinen,Korpiola, eds,Dying Prepared in Medieval and Early Modern Northern Europe, p. 156. ↩

-

Beyond Der schwangeren Frauen und Hebammen Rosengarten, the selected texts were Frawen Rosengarten. Von vilfaltigen sorglichen Zufällen und gebrechen der Mütter und Kinder (1545) by Walther Hermann Ryff, Tröstlicher Bericht für schwangere Frauen (1563) by Johann Hugo, Ein Trostbüchlein für die Schwangern vnd Geberenden Weiber (1564) by Thomas Günther, Ehestandts Artzney (1565), by Rößlin’s son, Hebammenbüchlin (1572), by Adam Lonitzer, and the ordinances Ordnung einer Erbarn Raths der statt Regenspurg die Hebammen betreffende (1550), printed by Hans Khol, Reformation, oder Ordnung für die Hebammen: Allen guten Policeyen dienstlich (1573), by Adam Lonitzer. ↩

-

The selected texts were Hebammen-Schul Oder gründlicher Unterricht (1715) by Johann Georg Sommer, Kurtze, jedoch hinlängliche und gründliche Anweisung christlicher Hebammen (1735) by Barbara Widenmann, Neues Hebammen-Licht (1740) by Hendrik van Deventer, Erklärte Anatomie für Hebammen: samt derselben Nutzanwendung zur Praxis (1752) by Georg Friedrich Gutermann, Hebammen-Catechismus: hauptsächlich zum Gebrauch für Wundärzte und Hebammen auf dem Lande (1778) by Leonhard Jakob Katzenberger, Selbstbelehrung für Hebammen (1797) by Johann Heinrich Jördens, and the ordinances Verneuerte und vermehrte Brandenburgische Hebammen-Ordnung (1743), published by Christoph Messerer, and Ordnung für die Hebammen in München (1791). ↩

-

You can see the standard German stopword list here: https://github.com/mimno/Mallet/blob/master/stoplists/de.txt ↩

-

You can see the Fraktur stopword list here: https://github.com/nkkafer/FrakturStopwords/blob/main/stopwords_fraktur.txt ↩

-

Hobby, The Birth of Mankind, 2. ↩

-

Baldassarri, Plants in 16th and 17th Century, 6. ↩

-

Der schwangeren Frauen und Hebammen Rosengarten, p. E. ↩

-

Wesiner, “the midwives of South Germany”, 83. ↩

-

Stolberg, “the decline of Uroscopy in Early Modern Learned Medicine (1500-1650)”, 313-36. ↩

-

Verwaal, Bodily Fluids, Chemistry and Medicine in Eighteenth-Century Boerhaave School, 92. ↩

-

Wesiner, “The Midwives of South Germany”, 83. ↩

-

“Mining the Dispatch,” https://dsl.richmond.edu/dispatch, accessed on December 13, 2021. ↩

Author

Natacha Klein Käfer,

University of Copenhagen and Lund University, nkk@teol.ku.dk,