Louis XIV's taste as a private matter: A Preliminary Outline of the Appartement du Roi's Iconography

Abstract

It is the object of analysis that imposes one or more methods from time to time; it is the result of the analysis that decides on the fruitfulness of the chosen method or methods. When we affirm the need for infinite analysis, this is precisely what we are referring to: the possibility of calling everything into question using analytical reagents of different composition.1 2

Introduction

The flamboyant and kaleidoscopic character of Louis XIV appears to continually defy the historian’s need to identify a specific characteristic, a recurring attitude, or an unexpected posture useful for organising the multitude of objects and artworks collected or commissioned by him according to one or more familiar thought patterns. In short, the extreme abundance and intrinsic dissonance of the material world surrounding him do not aid in discerning the taste of the Sun King. This assertion might appear anachronistic upon rigorous analysis. The word goût, or gusto in Italian, until the end of the 16th century, signified a spiritual refinement practice through which the devout could have a more intimate connection with the Christian God. 3 It was in the early succeeding century that the religious meaning of goût crossed into secular semantics, becoming a distinguishing feature of the amateur, someone capable of recognising the value of a work of art. 4

Simultaneously, taste was not the only parameter contributing to the formation of the grand 17th century collections in the hands of princes, nobles, and wealthy persons, often comprised of hundreds of works. The inherent logic of an increasingly growing art market should be contextualised on a case-by-case basis in its geographic and cultural implications. In most cases, this would lead to determining their origin and development based on political or personal prestige rather than the mere use of paintings as decorative objects for wall surfaces.5

Claiming that works of art in the 17th century were acquired or commissioned for pure pleasure or artistic interest is, therefore, a hypothesis that lacks eminent historiographic value. Its confirmation would require disciplinary means external to art history. However, the very excess of sources related to the life of Louis XIV6 —those that initially seemed to prevent us from accessing a possible interpretative key—could guide us toward uncharted terrain that may prove fertile for understanding his taste.7 First of all, to obviate the problem that the very form of inquiry raises, I will define as taste the gap between a cultural and a pragmatic-functional choice. This definition does not rely on scientific bases, nor does it claim disciplinary validity. Its utility lies simply in considering works of art —i.e., Louis XIV’s painting collection— for their nature as painted surfaces rather than for those attributes that make an artwork a unique and unrepeatable object, like the symbolic, economic, and emotional value. In short, the proposed method of inquiry regards Louis XIV’s collection as a single homogeneous source, rather than as a group of objects with diverse historical, cultural, and economic qualities.

This simplification also facilitates the analysis of the relationship between the work of art and its context. If the artworks are considered solely from their iconographic nature, which is thus measurable, the same treatment is applied to Versailles, their architectural context. Therefore, Louis XIV’s taste is not analysed through the social, symbolic, and ceremonial connotations implied by the spaces of the château.

Nonetheless, Versailles, as the context of Louis’s painting collection, was meaningful for several reasons. The first is that Versailles partly emerged as the destination of the Cabinet des Tableaux. Even before the palace emerged as the permanent residence of the court (1682), it became the destination for most of Louis’s personal and the Crown’s collections from the end of 1671. 8

The second is that Versailles was not always and everywhere an art gallery but a residence with varying degrees of accessibility and, therefore, privacy. The art collection moved —quite literally, given its mutability— between antechambers, chambers, salons, cabinets, and bed-rooms, all accessible to Louis, and in which he himself authorised access to a select number of individuals.9

The third is a corollary of the first two. By moving the Cabinet des Tableaux to Versailles and controlling its degree of privacy —which marked spaces from nearly entirely public to inaccessible— each change in the placement of an individual painting within a Versailles room takes on a different value. In some cases, those in which the choice deviates from cultural or pragmatic necessity, these changes, I argue, can define the monarch’s taste.

To detect these changes in the arrangement of paintings at Versailles —in some cases limited to a few items— by Louis XIV, I adopted a digital humanity approach. For that, I have identified and classified the paintings belonging to the Cabinet des Tableaux of the king, which were collected in Versailles after 1671, when the first part of the Cabinet was established in the palace.

The painting collection —that constituted a fraction of his and the Crown’s general art collection— was so extensive that only the plain citation of all the œuvres’ titles would take more than 5000 words. Moreover, the consistency of the collection at the times of Louis reached a complexity that its formation’s assessment has required the study of specific temporal and physical segments.10 The paintings were scattered, their location often changed, and the written sources about them, though plentiful, are sometimes contradictory. A digital humanities approach can aid in relating images to written documents and vice-versa, which can help us visualise relationships between these different historical sources, especially relationships that have not yet been considered. Moreover, such relations can also be interrogated as a meta-source that can help validate the historical macro perspective alongside the micro-analysis.

Louis XIV’s collection was formed from the initial collection of Francis I, and grew successively through a succession of bulk purchases or requisitions from other collectors, on the one hand; on the other, through commissions to artists contemporary with him and predominantly French.11 Therefore, digital humanities tools can unveil potential relationships between the items’s historical attributes (provenance, period of production and acquisition, author’s school, size, iconography, etc.) to local features (position and movements within Versailles, juxtaposition to other paintings, degree of privacy of the room, etc.).

From texts to images

The primary sources are mainly the inventories compiled by the peintres du roi: the anonymous Mémoire des tableaux qui sont posés dans les appartements du château de Versailles. Du premier novembre 169512; André Félibien’s Tableaux du Cabinet du Roy13; Charles Le Brun’s Inventaire des Tableaux du Cabinet du Roy of 168314 (Fig. 1); Jean-Aimar Piganiol de La Force’s three editions of his Nouvelle description des chateaux et parcs de Versailles et de Marly from 1701, 1707, and 1717 15; and the Inventaire des tableaux du Roy compiled by Nicolas Bailly from 1709 and 171016. Additionally, I benefitted from Mathieu Lett’s study in which he first commenced the data systematisation of the collection in the petit appartement17.

The written sources allowed the identification of 931 paintings present in Versailles from the palace’s establishment as one of the locations of the Cabinet des Tableaux in 1671 until Louis XIV died in 171518 (Fig. 2). All the items have been individually assessed by a number of fields, aiming to unveil the individual intrinsic features and relate each element within the general collection’s qualities. The data have been organized within a spreadsheet that contains the initial findings, and deploys the derived values, such as the paintings’ area, the production date range —if not already known— and the iconographic description (Fig. 3).

The resulting matrix bears, first, the sources where the items appear. This operation keeps an account of the consistency of the primary references, and it records the eventual discrepancies of location and timing among the different authors. Second, the section of the painting’s authorial information reveals the contemporary and historical attributions, and thus sheds light on the taste and motivations expressed within Louis’ acquisitions, the artistic school’s relevance, and, potentially, on the painting’s spatial collocations and the significance of their movement. Third, the spatial location of the paintings —although for some items the sources only give a generic location, i.e. Versailles— permits to reconstruct the detailed geography of the positioning and movements of the paintings, especially for those gravitating to the king’s private apartments. Fourth, the date framing considers the multiple relations occurring between the author’s biographical dates, the painting production (potentially deducted from the latter or indicated in primary or secondary sources) and the date of acquisition (also indicated in the primary sources or inferred from the relation between production date and accounting of possess). These data are enhanced by the information retrieved on the provenance of the paintings within the Crown’s collections together with the status of the artwork and its location within the contemporary public domain. Last and most important, the manual attribution —achieved analysing the painting or guessing from the source’s description in the case of lost works— of the Iconclass codification of all the 931 items. 19

Iconclass aims to provide a coherent classification structure by pictorial subject, overcoming the lengthy and time-consuming description of the actual artworks 20. The Iconclass attribution spans the nine iconographic classes relevant for our period of interest21, and detects the main iconography within the first 450 sub-categories ranging from the sacral formulas like Angels, Saints, God Father, Virgin Mary, et al., to profane themes like the historical portraits, depiction of festivities, parties, hunting, sport activities, passion, love, etc. Further analysis of the artworks permits access to the contextual semantics of the specific scene, attributing one concept among the 2,5 million iconographies available.

Any iconographic concept is expressed within a chain that locates it according to the accuracy of the subject detected. For example, the Iconclass alphanumerical notation of Paolo Veronese’s Esther before Ahasuerus (Fig. 4) displayed at the Antichambre de l’ Œil-de-Bœuf would be expressed as follows:

7 Bible

71 Old Testament

71Q the story of Esther

71Q6 Esther before Ahasuerus (Esther 5:1-4)

71Q63 Esther swoons on the shoulder of one of her maids (Esther 15:7)22.

The use of Iconclass allows the data collection of the Cabinet des Tableaux to exhibit the evidence of Louis’ taste for a specific iconography in relation to the other data, like time, location within the residence —whether public or private—, artistic school, size of the painting, or type of commission (acquisition or assignment).

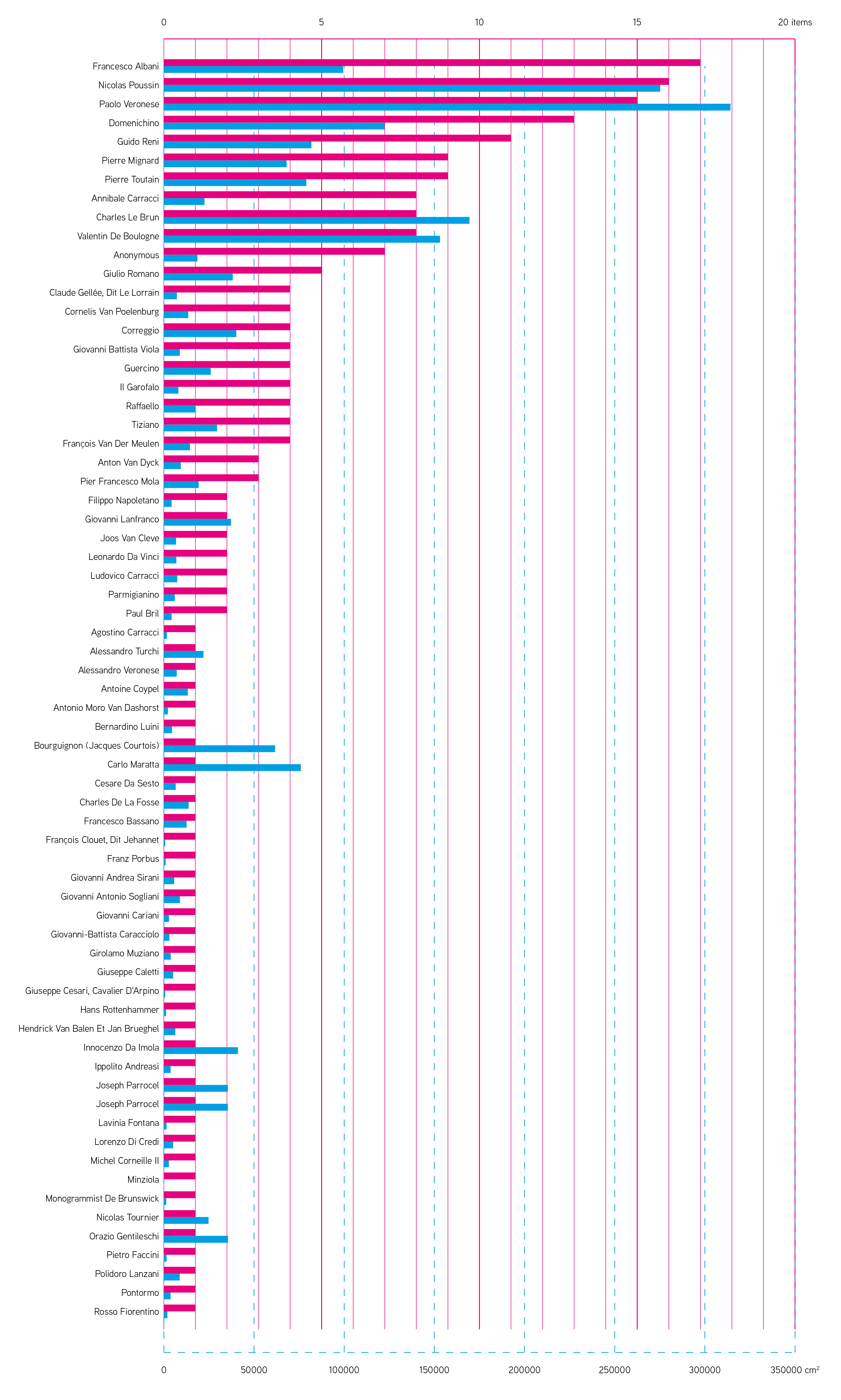

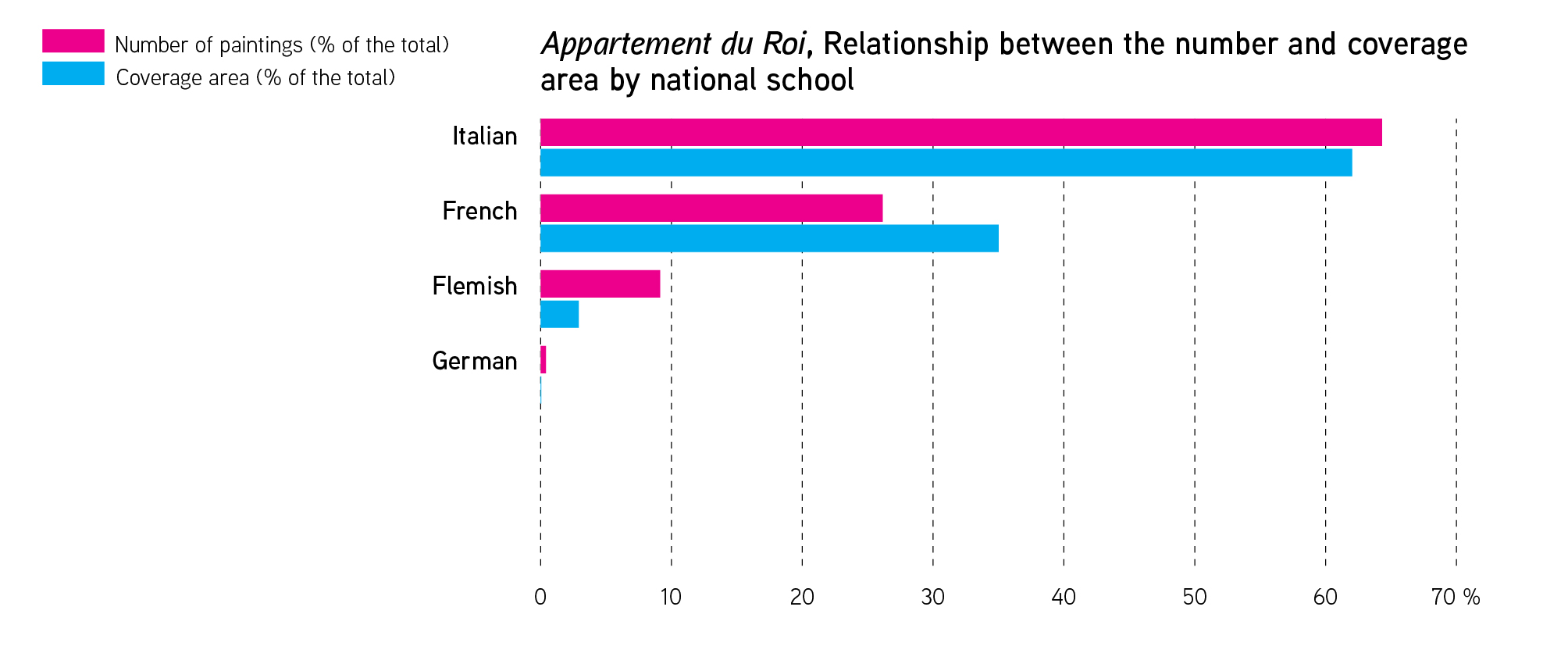

The spreadsheet underwent several reiterations, and it served as entry material for an initial digital process conducted with Python. This programming language made it possible to analyse the cross-relationships between the material and immaterial attributes of the paintings that reveal an attitude of Louis XIV’s personal preference. Therefore, of the many possibilities offered by the cross-checking of the data, I focused on the evidence of Louis’s taste emerging from his conscious selection of paintings operated within his apartments. One example is the relationship that emerged between the nationality/school of the authors, the number of paintings present, and their area (Fig. 5).

What emerges is the overall greater importance of the Italian school in terms of number of paintings and painting area. At the same time, some cases (Francesco Albani, Domenichino, and Guido Reni above all) show the discrepancy between the average number of items and the painted surface. This occurs due to the traditional smaller size of the works realised in Italy between the late 15th and early 17th century compared to the late 17th century French paintings. Far from being a mere technical specification, this remark must be taken in consideration to evaluate the influence of an iconography in relation to the painting’s reach. A second set of data parsing has been conducted relating the iconographic qualities to the quantitative data, like the number of paintings and the painting coverage by author, or to the production and acquisition’s dates.

Paintings in context

The considered rooms are not just those that, traditionally, historiography identifies as the private part of the king’s abode, namely the Petite Galerie. On the contrary, due to the architectural transformations from Versailles’s inception to Louis’s departure —or, at least, until 1701— the Cabinet des Tableaux was displayed in the Appartement du Roi, namely those rooms that went from the Salle des Gardes to the Cabinet des Medailles, which had an independent access from the Grand Appartements. Additionally, from the chronological perspective, the earliest inventory dates from 1695, which limits our inquiry to the last 20 years of Louis’s reign. 23

The Appartement du Roi consisted of 14 rooms forming a sequence that dictated the liturgical approach —hence the proximity— to Louis. This sequence had one main access (the queen’s staircase) and, according to the person’s rank and the reason for the visit, the approach would have ended at the Salle des Gardes or, in the best case, at the Petite Galerie (Fig. 6). Depending on the penetration’s level into the king’s suite, and the frequency of the visits, a certain type of arrangement of paintings —a particular access to Louis’s taste— could therefore be detected. The daily attendees to the king’s lever at the Chambre du Roi, for example, would hardly miss any change in the display of the collection until the Salle du Conseil. However, the rooms they walked through were rarely subject to any transformation. On the contrary, an extraordinary guest — a diplomat or a foreign prince— would have had access to the deepest part of the apartment and would therefore have encountered the most intimate taste of the king. However, due to the exceptionality of the visit, unique guests could not observe changes or deliberate choices in the iconographic display ordained by the king.

Spatial references

The source for detecting the spatial distribution of the collection within the Appartement du Roi is the Nouvelle description des chateaux et parcs de Versailles by Jean-Aimar Piganiol de La Force in his three consecutive editions of 1701, 1707, and 1717 (Fig. 7). If the latter is substantially like the one of 1707 —however bearing some interesting additions— the first two recorded the substantial apartment’s transformation of 1701. It seems plausible that Piganiol visited the royal residences some years before publishing the guide. In the 1701 edition the sequence started at the Salle des Gardes and continues with the Antichambre du Roy, the Chambre du Roy (previously the Chambre de la Reyne), the Grand Salon, and the Salle du Conseil, before introducing the most secluded sequence of rooms. The 1707 and 1717 editions registered the creation of the Œil-de-Bœuf (called Grand Sallon) as the new Chambre du Roi’s antechamber (that took the central position of the previous Grand Sallon), followed by the enlarged Salle du Conseil. The following rooms —if not for the nomenclature— did not change in Piganiol’s description. The sequence is formed by the Cabinet du Billard, the Vestibule du Petit Escalier, the Deuxième Antichambre du Cabinet des Tableaux, the Cabinet des Tableaux, the Cabinet des Coquilles, the Sallon de la Petite Gallerie, the Petite Galerie. The Cabinet Des Medailles, due to its unique entrance from the Salle de l’s Abondance, is described within the Grand Appartements. Significantly, Piganiol, contrary to Félibien in his Tableaux du Cabinet du Roy, proceeded his literary journey by describing the the king’s residence as a sequence ofrooms —that had already reached their architectural completeness— characterising these only by the displayed paintings’ features. The author was conscious of the artistic and socio-political implications embedded in the arrangement of the Appartement du Roi, especially after the transformation of 1701. None of the authors makes explicit reference to the position of the paintings on the walls. Nor can one legitimately assume that the descriptions follow a recurring order, from top to bottom and clockwise, or vice versa.

However, it should be considered how the Appartement du Roi consists of a sequence of rooms whose use and access, from the Salle des Gardes to the Cabinet des Medailles, closely express the modern concept of transition between the public and the private. Thus, the display of the collection along this long spatial transition reveals the aforementioned gap between a generic cultural influence in the acquisition or commissioning of paintings, and a merely decorative use of the pictorial apparatus typical of the 17th century. In short, an analysis of the collection in the Appartement du Roi is capable of revealing Louis XIV’s taste.

An iconographic reading

Proceeding in the analysis of the king’s painting collection —intended as a unitary source— from its intrinsic pictorial value, namely the iconography, and from its unavoidable relation to architecture —thus forming the Cabinet des Tableaux—the collected data offer a valuable perspective regarding Louis’s taste.

The first evidence is quantitative. The 931 paintings forming the collection located in Versailles covered an area of 1576 m², equal to a square with a side of almost forty meters.24 The numbers do not look impressive, even if compared to contemporary European collections. However, these quantities must be considered for the enormous possibilities that the combination of the paintings would have offered, and for the few —hence, driven by a specific taste— that have been realized.

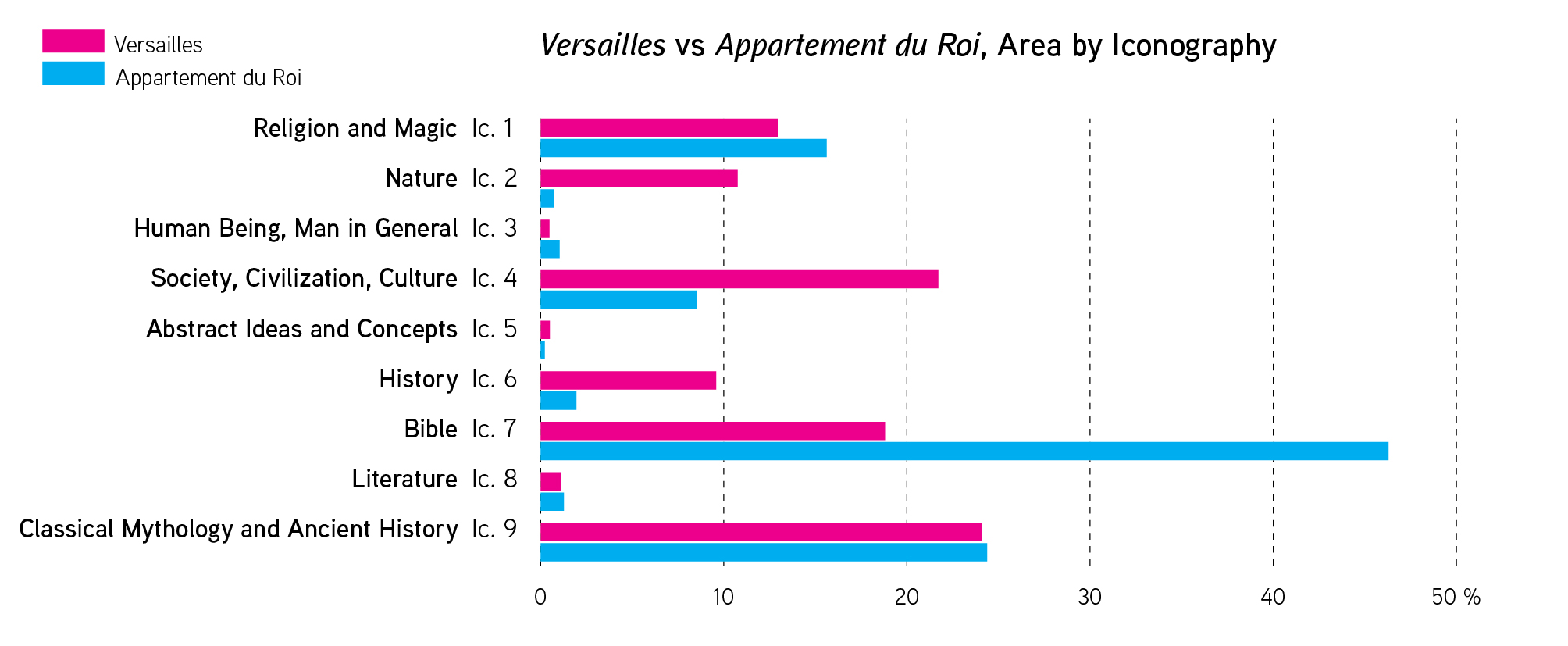

The most frequent general iconographies found in Versailles were Biblical (Ic. 2: 204 paintings, 21,9% of the total), Classical Mythology25 (Ic. 9: 192 paintings, 20,6%) and Society, Civilisation, Culture (Ic. 4: 189 paintings, 20,3%). The collection also covered the categories of Nature (Ic. 2: 21, 13%), and Religion and Magic (Ic. 1: 114, 12,2%). The first three iconographies shared a similar ratio in terms of covered surface: 25,3%, 24,2%, and 19,2% respectively, for a total of 68,7% of the total paintings’ area within the château (Fig. 8).

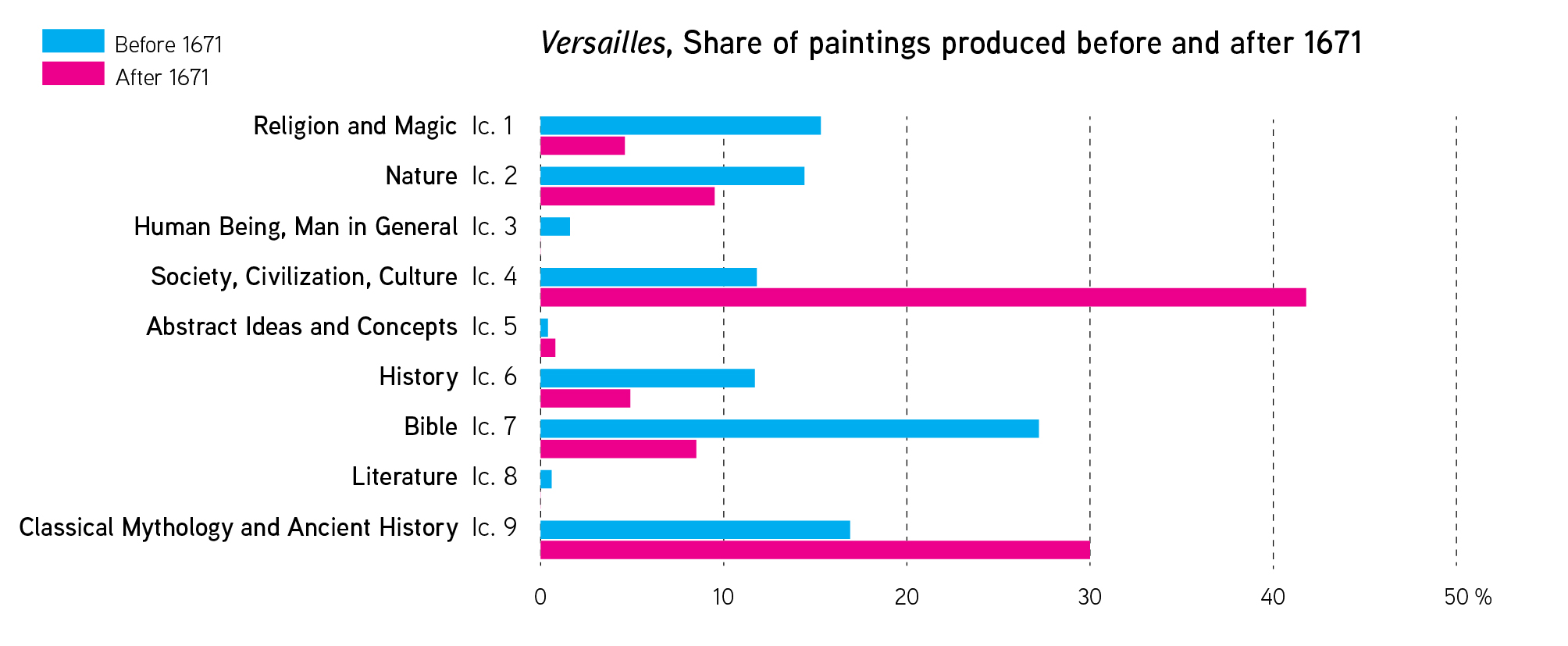

Despite the apparent similarity of these three iconographic categories in terms of material presence, the most interesting quality for all the classes stands in their paintings production timeframe ratio. If the Mythological iconography shares an equal number of paintings produced before and after Louis became king in 1654 (97 versus 95), the other classes —exception made for Abstract Ideas and Concepts that, counting only five items, makes the statistic irrelevant— are unbalanced towards one or the other period (Fig. 9).

Clearly, the elevation of 1654 as the year of clear separation does not add any argument per se about the assessment of the individual paintings, that would require a specific historical study. However, it can offer a good sense of the iconographic preferences and Louis’s personal influence on creating his collection. More interesting is to argue whether the second Jabach sale in 1671 can stand as a clear demarcation in the paintings’ production in relation to —thought, historically, not only— the presence of the Sun King on the market.26 It emerges that Biblical iconography was acquired through works mainly produced in a previous time (182 versus 22). The bulk of the Biblical iconography was produced by Italian artists (140 paintings), completed by 27 paintings by French artists and 15 by German and Flemish painters. At the same time, Society, Civilisation, Culture was a much more contemporary artistic interest, counting 78 works already on the market, versus 110 produced while Louis XIV was expanding his collection (Fig. 10).27 There is a correlation between the king’s iconographic interest in works categorized under Iconclass 4 and the contemporary artistic offer. This analysis, taking into account the authorial origin of the works, shows how the Sun King —as an artistic— patron favoured the French school representatives.28 This evidence foregrounds the Italian hegemony on the painting until the middle 17th century and, at the same time, the loss of interest in such iconography within the French king’s court.

Similarly, examining the Mythological iconography, a shift occurred between 1654 and 1671. While there is a parity before the coronation (97% of Iconclass 9 produced before 1654 versus 95% afterward), the second Jabach sale represented the achievement of the French cultural supremacy that benefitted from the mythological formulas imported from Italy.

Considering the paintings produced before 1671, the collection listed 49 items produced by 23 French painters; on the Italian side, there were 53 works by 22 artists. After 1671, the French school added 77 more (from 20 painters) versus only one artwork coming from the Italian Peninsula. This discrepancy occurred because, in 1671, the effects of Colbert’s co-opting of the Académie for the promotion of the French artists caused the almost complete replacement of the private commissions, thus determining a long-lasting influence on the iconography.29

The balance attained before 1671 was achieved mainly through the strong presence of two artists that, differently, encountered the taste of the king: Francesco Albani and Nicolas Poussin.

The Appartement du Roi

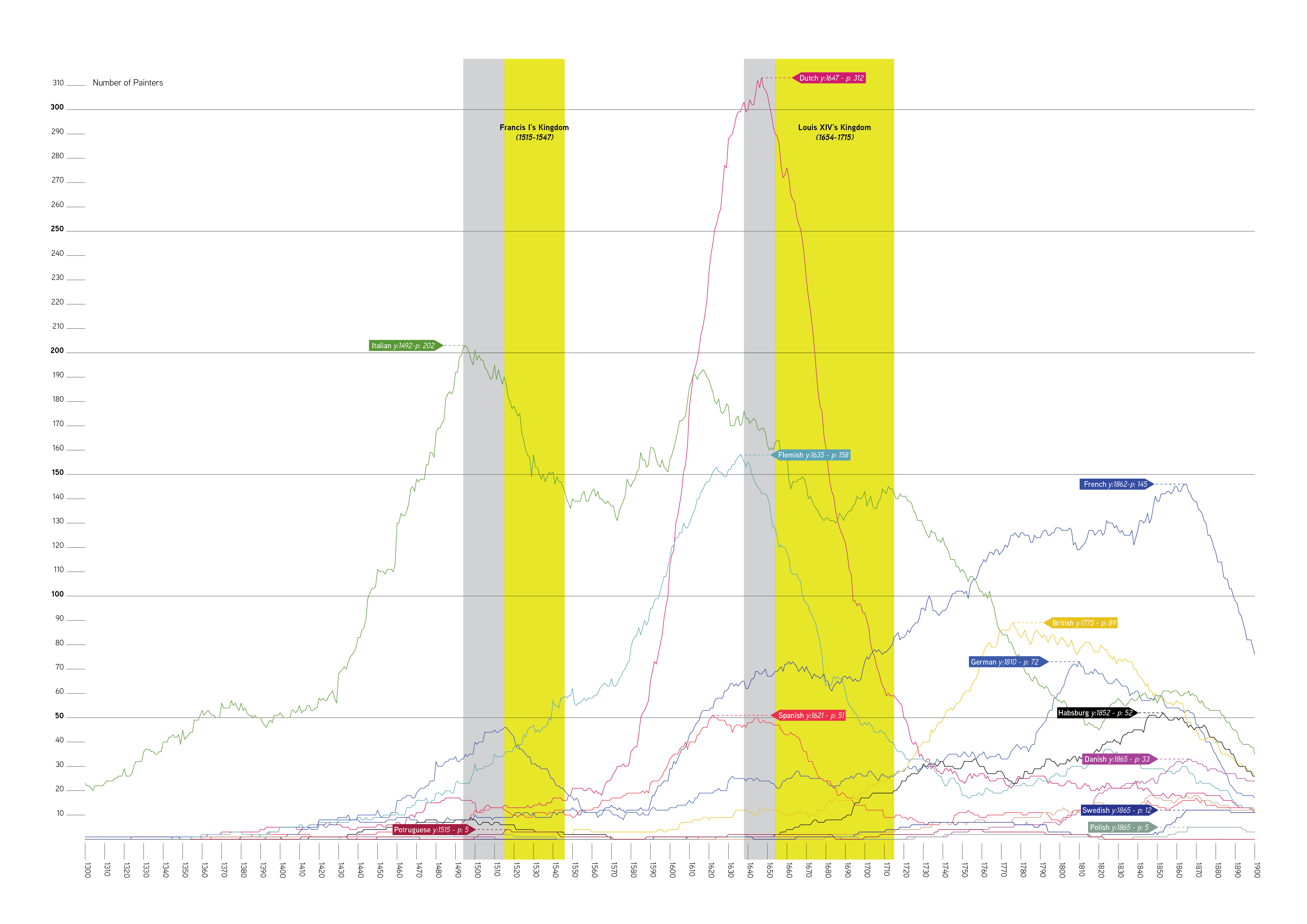

Looking at the time span of Louis XIV’s reign in relation to the presence of artists by nationality, it seems no coincidence that his interest in art collections and his promotion of French artists through the Académies corresponds to a steady growth of the latter (Fig. 11).30

The emblematic missions of Paul Fréart de Chantelou in Italy (1640 and 1643) meant to discover and import Italian masterpieces to the French homeland (and to bring home painters like Nicolas Poussin) were just the tip of the iceberg of the cultural struggle which, soon, would see the French culture prevailing. 31

This cultural context is reflected on the Appartement du Roi’s composition. The 241 paintings present in his apartment were produced by an array of 76 artists: 51 Italians, 13 French, 11 Flemish, and 1 German. The apparent supremacy of the Italian school was, nonetheless, levelled by the proportion in surface coverage. While considering the absolute numbers, Italian artists were the 64% of the total compared to the 23% of Frenchmen, the area covered saw a gap between them of only 27% (62% versus 35%) (Fig. 12).

While the German painters occupied a limited position in terms of number or physical appearance, the French school’s rising position in the European context was the effect of the Bourbon’s artistic promotion commenced under Louis XIII (and supported by cardinal Richelieu).32

The Dutch school saw a dramatic fall in numbers from the emergence of Louis XIV’s influence. The Cabinet des Tableaux in Versailles recorded a Dutch and Walloon presence with a total of only eight paintings, covering barely 2,3% of the total surface. Moreover, examining the bold Italian presence, it appears that among the 42 Italian painters, only four were contemporaries of Louis XIV: Guercino (1591-1666), Pier Francesco Mola (1612-1666), Carlo Maratta (1625-1713), and Giovanni Andrea Sirani (1610-1670). Exception made for Guercino, they were not even among the most renowned artists of the Peninsula. Linking this common consideration to the evident decrease of the Italian representatives, it appears that Louis’s notorious attention for Italian art, often mentioned in historiography, was directed towards a pure collecting of pieces from the past. Conversely, the French counterpart —counting 13 painters— included ten of the king’s contemporaries. This was the sign that Louis surrounded himself with the emergent or established living national artists, whose career was boosted by the establishment of the Académie. This evidence also emerged from the overlap of the work production timeframe referred to the complete collection of 931 artworks present in Versailles.

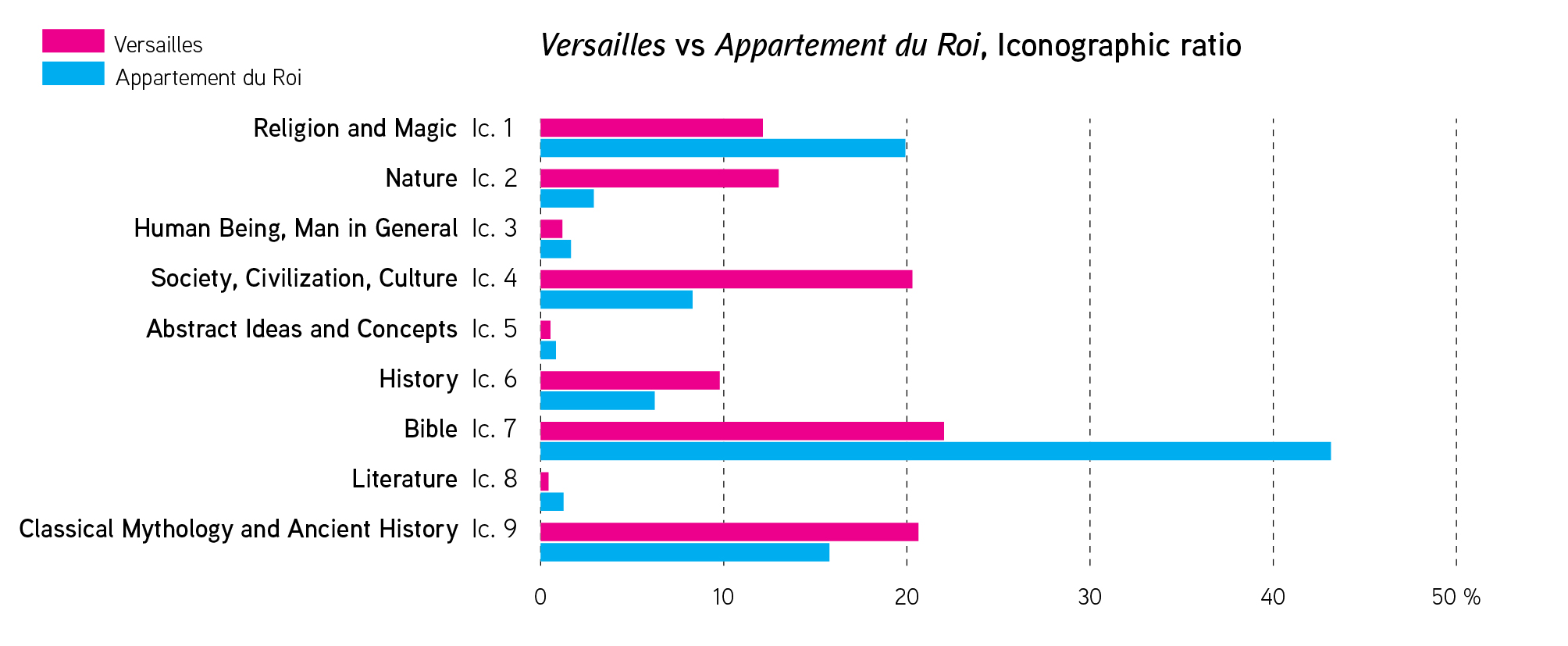

How should we then describe Louis XIV’s taste and iconographic preferences whilst exploring the Cabinet des Tableaux through the tight linkage to the most secluded spaces of the Appartement du Roi? Considering only the 241 paintings (26% of the total) detected from the above-mentioned sources displayed from the Salle des Gardes to the Cabinet des Medailles, the iconography balance among the 9 Iconclass classes is very different from the entire corpus of paintings.

While in the entirety of Versailles, Ic. 1, 3, 5, 6, and 9 coexist in a similar material and numerical presence, in his personal collection, Louis XIV gave emphasis to the Biblical iconography that was represented by the 43,1% (versus only 22,0% in the entire collection), at the expenses of iconographies of Nature (2,9% vs 13,0%), and Society, Civilisation, Culture (8,3% vs 20,3%) (Fig. 13). The prevalence of biblical iconography is even more pronounced if one considers its size in terms of area of coverage of biblical paintings: in this case the Appartement’s share rises to 46.3% against 18.8% for the entire collection. (Fig. 14).

The reasons are, as often happens, not attributable to a univocal fact or cause. The strong presence of paintings of the 16th and early 17th century on the market at the time of the king’s acquisitions could explain the prevalence of religious, and specifically, Biblical iconography. Looking at the morceau de réception required as acceptance at the Académie in its early times, the landscapes, still life, and the mythological scenes did not completely replace the traditional formulas. 33 Yet, the predominance of Italian artists (155 Italians versus 63 French) from a previous epoch in relation to Louis’s collection is clear; within this research path, it does not define a cause, but it is part of the inquiry itself.

However, it cannot be excluded that the predominant presence of Biblical iconography in the Appartement du Roi is the result of a choice related to Louis XIV’s taste. And that this choice would reveal an aspect of the monarch’s private condition, which, although influenced by general cultural conditions, operates outside of a merely decorative use of the pictorial surface.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the ongoing study’s main goal was to determine the emergence of the taste in Louis XIV’s adoption of a specific iconography as evidence of the privacy’s inception within the Appartement du Roi in Versailles.

The paper showed how the Appartement, given its status as an expression of the king’s private sphere, was the place where his taste most conspicuously emerged. Moreover, the king’s taste was determined by indissoluble link between the Appartement and the corresponding section of the Cabinet des Tableaux. Finally, the digital approach offered a critical methodology to define and quantify the object of the realm of taste for a painting collection. By assessing a significant number of data points that, in their entirety, ascertain the value of a broader perspective of investigation without neglecting the closer analysis.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Anonymous. ‘Mémoire des tableaux qui sont posés dans les appartements du château de Versailles. Du premier novembre 1695’, 1 November 1695.O/1/1964/7.18. Archives Nationales.

Bailly, Nicolas. Inventaire des tableaux du Roy rédigé en 1709 et 1710 par Nicolas Bailly. Edited by Fernand Engerand. Ernest Leroux,1899.

Félibien, André. Tableaux du Cabinet du Roy. Statues et bustes antiques des Maisons royales. Vol. 1. Paris: Impr. royale, 1677.

Le Brun, Charles. ‘Inventaire des Tableaux du Cabinet du Roy’. Paris, 1683. O/1/1964-8. Archives Nationales.

Piganiol de La Force, Jean-Aimar. Nouvelle Description Des Chasteaux et Parcs de Versailles et de Marly: Contenant Une Explication Historique de Toutes Les Peintures, Tableaux, Statues, Vases et Ornemensqui s’y Voyent: Enrichie de Plusieurs Figures En Taille Douce. Seconde Edition. Florentin Delaulne, 1707.

———. Nouvelle description des châteaux et parcs de Versailles et de Marly. Paris: Chez Florentin Delaulne, 1717.

———. Nouvelle description des chateaux et parcs de Versailles et de Marly: contenant une explication historique de toutes les peintures, tableaux, statues, vases & ornamens qui s’y voient ;leurs dimensions ; & les noms de peintres, & des sculpteurs qui les on faits. Avec les plans de ces deux maisons royalles. Chez Florentin & Pierre Delaulne, 1701.

Secondary Sources

Brejon de Lavergnée, Arnauld. L’inventaire Le Brun de 1683: la collection des tableaux de Louis XIV. RMN, 1987.

Castelluccio, Stéphane. Les collections royales d’objets d’art: de François Ier à la Révolution. Éditions de l’Amateur, 2002.

Chennevières, Philippe de, Eugène Daudet, and Anatole de Montaiglon. ‘Sujets des morceaux de réception des membres de l’ancienne Académie de peinture, sculpture et gravure, 1648 à 1793, recueillis par m. Duvivier, de l’École impériale des beaux-arts, d’après les registres de cette académie, avec l’indication de l’emplacement actuel d’un certain nombre de ces ouvrages’. Archives de l’art français 22 (1852): 353–91.

Couprie, L. D. ‘Iconclass: An Iconographic Classification System’. Art Librarian Journal, no. Summer (1983): 32–49.

Hulftegger, Adeline. ‘Notes sur la formation des collections de peintures de Louis XIV: (l’ entrée dans le Cabinet du Roi des tableaux provenant de Jabach, Mazarin, Fouquet etc. ...)’. Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art Français, 1955, 124-34.

Krén, Emil, and Dániel Marx. ‘Web Gallery of Art’. Accessed 23 November 2021.https://www.wga.hu/index1.html https://www.wga.hu/index1.html

Lett, Mathieu. ‘Les tableaux du Petit Appartement de Louis XIV à Versailles (1684-1715)’. In Louis XIV, l’image et le mythe, edited by Mathieu Da Vinha, Alexandre Maral, and Nicolas Milovanovic,97–123. Collection Histoire: Aulica. Rennes : Versailles: Presses universitaires de Rennes ; Centre de recherche du château de Versailles, 2014.

Moriarty, Michael. Taste and Ideology in Seventeenth-Century France. Cambridge Studies in French. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Van De Waal, Hans, L. D. Couprie, E. Tholen, and G. Van Caspel-Vellekoop. Iconclass an Iconographic Classification System. North-Holland, 1975.

Van Caspel-Vellekoop. Iconclass an Iconographic Classification System. Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1975.

Endnotes

-

Tafuri, Manfredo. “Sklovskij, Benjamin e la teoria dello «spostamento».” Figure. Teoria e Critica dell’Arte 1, no. 1 (1982): 38–51. My translation. ↩

-

This paper is part of a research funded by the Centre for Privacy Studies, Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF138). ↩

-

Aceti de’ Porti, Serafino. Opere spirituali, alla christiana perfettione, vtiliss. & necessarie. Del r.p. don Serafino da Fermo can. reg. lat. & predicatore feruentissimo. Nuouamente con somma diligentia riuiste, & da infiniti errori purgate, & alla sua primiera integrita, con molte aggionte, restituite: come nella seguente. Piacenza: Francesco Conti, 1570. ↩

-

Taylor, Paul. “The Birth of the Amateur.” Nuncius / Museo Galileo, no. 3 (2016): 499–522. For the specific French case, see Fumaroli, Marc. “Rome 1630: entrée un scéne du spectateur.” In Roma 1630: il trionfo del pennello, edited by Olivier Bonfait, 53–82. Milano: Electa, 1994. ↩

-

Schnapper, Antoine. “The King of France as Collector in the Seventeenth Century.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 17, no. 1 (1986): 185–202. ↩

-

Burke, Peter. The Fabrication of Louis XIV. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992. ↩

-

While the nature and composition of Europe’s great art collections has been the subject of various scientific research, understanding their purpose and function is a matter of debate and does not necessarily imply an unequivocal answer. For a discussion on this subject in the French context see: Schnapper, Antoine. Le géant, la licorne et la tulipe collections et collectionneurs dans la France du XVIIe siècle. Paris: Flammarion, 1988. ↩

-

Brejon de Lavergnée, Arnauld. “Le cabinet du roi.” Connaissance des arts 433 (1988): 52–63. ↩

-

Hulftegger, Adeline. “Notes sur la formation des collections de peintures de Louis XIV: (l’ entrée dans le Cabinet du Roi des tableaux provenant de Jabach, Mazarin, Fouquet etc. …).” Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art Français, 1955, 124–34. ↩

-

Brejon de Lavergnée, Arnauld. L’inventaire Le Brun de 1683: la collection des tableaux de Louis XIV. Paris: RMN, 1987. ↩

-

Schnapper, Antoine. “Préface.” In L’inventaire Le Brun de 1683: la collection des tableaux de Louis XIV, by Arnauld Brejon de Lavergnée, 5–10. Paris: RMN, 1987. ↩

-

The document A.N., O119647.18 of the Archives Nationales has been firstly published in Stéphane Castelluccio, Les collections royales d’objets d’art: de François Ier à la Révolution (Paris: Éditions de l’Amateur, 2002): Annexe 3. ↩

-

André Félibien, Tableaux du Cabinet du Roy. Statues et bustes antiques des Maisons royales, vol. 1 (Paris: Impr. royale, 1677). ↩

-

Charles Le Brun, ‘Inventaire des Tableaux du Cabinet du Roy’ (Paris, 1683), O/1/1964-8, Archives Nationales. Arnauld Brejon de Lavergnée, L’inventaire Le Brun de 1683: la collection des tableaux de Louis XIV (Paris: RMN, 1987). ↩

-

Jean-Aimar Piganiol de La Force, Nouvelle description des chateaux et parcs de Versailles et de Marly: contenant une explication historique de toutes les peintures, tableaux, statues, vases & ornamens qui s’y voient ; leurs dimensions ; & les noms de peintres, & des sculpteurs qui les on faits. Avec les plans de ces deux maisons royalles. (Paris: Chez Florentin & Pierre Delaulne, 1701). Jean-Aimar Piganiol de La Force, Nouvelle Description Des Chasteaux et Parcs de Versailles et de Marly: Contenant Une Explication Historique de Toutes Les Peintures, Tableaux, Statues, Vases et Ornemensqui s’y Voyent: Enrichie de Plusieurs Figures En Taille Douce, Seconde Edition (Paris: Florentin Delaulne, 1707). Jean-Aimar Piganiol de La Force, Nouvelle description des châteaux et parcs de Versailles et de Marly (Paris: Chez Florentin Delaulne, 1717). ↩

-

Nicolas Bailly, Inventaire des tableaux du Roy rédigé en 1709 et 1710 par Nicolas Bailly, ed. Fernand Engerand (Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1899). ↩

-

Mathieu Lett, ‘Les tableaux du Petit Appartement de Louis XIV à Versailles (1684-1715)’, in Louis XIV, l’image et le mythe, ed. Mathieu Da Vinha, Alexandre Maral, and Nicolas Milovanovic, Collection Histoire: Aulica (Rennes : Versailles: Presses universitaires de Rennes ; Centre de recherche du château de Versailles, 2014), 97–123. ↩

-

The image portraits the exhibition “Tell me of Louis” held at Capo Space in Rome between November 2019 and January 2020. The exhibition aimed to visualize from one point of view the entire painting collection of Louis XIV in Versailles. The paintings were scaled down in 1:20, and organized along a 10 meters long strip according to the nine Iconclass categories. Gigone, Design by Office U67 ApS. ‘Tell Me of Louis’. Exhibition presented at the Campo Space, rome, 27 Novemebre 2019-27 January 2020. https://www.campo.space/fabio-gigone-tell-me-of-louis. ↩

-

Iconclass is a library classification conceived for art and iconography by Hans Van De Waal in the 1950s. The Iconclass iconographic attribution system is constantly being implemented and today covers more than 28,000 individual concepts. Van De Waal, Hans. Decimal Index of the Art of the Low Countries. Abridged Edition of the Iconclass System. The Hague: Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie, 1968. ↩

-

L. D. Couprie, ‘Iconclass: An Iconographic Classification System’, Art Librarian Journal, no. Summer (1983): 32–49. ↩

-

The classes are: Religion and magic (1); Nature (2); Human being (3); Society, civilisation and culture (4); Ideas and abstract concept (5); History (6); Bible (7); Literature (8); Myths and history of classic antiquity (9). Abstract art (0) is, obviously, not present. Hans Van De Waal et al., Iconclass an Iconographic Classification System (Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1975).Iconclass has been completely digitalized: ‘Iconclass’. Accessed 15 November 2021. http://www.iconclass.org/help/outline. ↩

-

“Test Iconoclass”, https://test.iconclass.org/71Q63 ↩

-

I mean any inventory meant to locate the paintings: Le Brun’s Inventoire did not have such scope, while Félibien’s Description sommaire du château de Versailles published in 1674 did not mention any detailed description of the paintings, hence the first account of the Versailles’s Cabinet des Tableaux that combines a description and a location of the paintings remains the anonymous’ A.N., O119647.18 of November 1695 and published by Castelluccio, followed by Piganiol de La Force’s Nouvelle description […]. ↩

-

The counting and, thus, the analyses, exclude the recessed and ceiling paintings. ↩

-

See note 9 for the list of Iconclass’s main classes. ↩

-

As Brejon de Lavargnée argues, the collection of the 483 paintings of the Cabinet de Tableaux recorded within Le Brun’s Inventaire in 1683 is the evidence of the chronology of the acquisitions pursued by Louis under the aegis of Jean-Baptiste Colbert. The acquisition lots are: Francis I’s ancien fond;the paintings donated to Louis XIII by the cardinal Richelieu; the first part of Eberhard Jabach’s collection (before 1666); a small part of the cardinal Mazarin’s collection; the donation of cardinal Flavio Chigi (1664); the collection of the Duc the Richelieu (1665); the donation of the Camillo Francesco Maria Pamphili (1665); the first Jabach sale (1666); eight paintings from Hoursel (1670); the second Jabach sale (1671); the Fouquet sequestration (1671); the acquisition of the collection of the mysterious La Feuille (1671); 52 paintings stocked at the Gobelins; the acquisitions from the merchant Alvarez (1681-1683); finally, other 56 paintings purchased before 1683 and in 1685-1686. The reconstruction of the origin of the collection —here extremely simplified— is contained in Le Brun’s Inventoire is published in Brejon de Lavergnée, Arnauld. L’inventaire Le Brun de 1683: la collection des tableaux de Louis XIV. Paris: RMN, 1987. Despite Brejon de Lavargnée declares that: “L'étude de la collection des peintures du banquier allemand Eberhard Jabach —deux cent une pièces,[…]— a toujours été difficile à ent reprendre, carl'historien ne possède ni les inventaires de ses deux premières collections, ni la liste officielle des tableaux qui furent acquis par le Roi”, this lot, however, clearly marks —for its chronology, modality, and consistency— the shift from a natural acquisition due to Louis’s royal prerogatives, and the king’s direct agency on the art market. ↩

-

The disclaimer of such argument is that I’m referring to the minimum production date, whose accuracy is not homogeneous for all the cases (Fig. 3), and whose relation to the general production time latitude might bring to potential different conclusions. ↩

-

The authors of the 110 paintings produced after 1671, and belonging to Ic. 4 are all French: Antoine Dieu, Antoine Monnoyer, Charles Le Brun, Claude Simpol, Etienne Allegrain, François Desportes, Jean Baptiste Monnoyer, Jean Cossiau, Jean Cotelle, Jean-Baptiste Belin De Fontenay, Jean-Baptiste Martin, Joseph Christophle, Joseph Parrocel, Madeleine Boullogne, Nicolas Bertin, Nicolas Spheyman, and Pierre Mignard. ↩

-

Pevsner, Nikolaus. Academies of Art: Past and Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1940. ↩

-

The diagram organises chronologically the distribution of the painters by the national school from 1300 to 1900. The labels indicate the school’s year peak and the number of active painters. The source is: Emil Krén and Dániel Marx, ‘Web Gallery of Art’, accessed 16 December 2023, https://www.wga.hu/index1.html. Diagram by the author, 2022. ↩

-

The supremacy of French culture over that of Italy is, if not the consequence, the other side of the coin of Louis XIV’s geopolitical ambitions in Europe. From a cultural point of view, one of the political instruments used was the establishment of the Académies, which favoured the inclusion of French artists within the propaganda mechanisms advocated by Louis XIV and Colbert, and which weakened the influence of the guilds and, consequently, the professional independence of the artists themselves. For a discussion on this subject see Pevsner, Nikolaus. Academies of Art: Past and Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1940; and Solinas, Francesco. “«Portare Roma a Parigi», mecenati, artisti ed eruditi nella migrazione culturale.” In Documentary culture Florence and Rome from Grand-Duke Ferdinand I to Pope Alexander VII, edited by Elizabeth Cropper, Giovanna Perini, and Francesco Solinas, 227–61. Bologna: Nuova Alfa, 1992. ↩

-

Hans Rottenhammer, and the Monogrammist De Brunswick. ↩

-

Philippe de Chennevières, Eugène Daudet, and Anatole de Montaiglon, ‘Sujets des morceaux de réception des membres de l’ancienne Académie de peinture, sculpture et gravure, 1648 à 1793, recueillis par m. Duvivier, de l’École impériale des beaux-arts, d’après les registres de cette académie, avec l’indication de l’emplacement actuel d’un certain nombre de ces ouvrages’, Archives de l’art français 22 (1852): 353–91. ↩

Author

Fabio Gigone,

Chair for the History and Theory of Architecture, ETH Zürich, gigone@arch.ethz.ch,