A Bridge Between Two Worlds

The Political and Economic Geography of SNCC's Friends Network

Abstract

In late 1962 and early 1963, government officials in Leflore County, Mississippi cut off the Federal Surplus Commodities Program. The decision was part of a deliberate effort by the White Citizens Council to derail the work of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In response, SNCC members wrote letters and sent out news releases to Northern supporters. Students and residents in northern communities responded. Ivanhoe Donaldson, a Black student at Michigan State University, gathered donations of food, clothing, and medicine and drove the supplies South.1 Julie Prettyman, opened up her notebook of wealthy and famous contacts in New York. In 1963, she helped organize a concert headlined by Harry Belafonte.2 The efforts of both Donaldson and Prettyman were connected to the work of a broad national network of organized “Friends of SNCC.” Following Donaldson’s trip from East Lansing to Mississippi, he started a “Friends of SNCC” at Michigan State University and later joined SNCC full-time. Prettyman became the organizing director of the New York Friends of SNCC. In late 1962, when SNCC drew on Northern resources, there were six chapters with a budget of $71,927. Two years later, with the expansion of Friends chapters to fifty-seven, the organization’s budget more than quadrupled to $350,000.3 Funds from the chapters supported fieldworkers, Freedom Houses and Schools, community centers, and voter registration drives.

Work by scholars such as John Dittmer, Charles Payne, and Wesley Hogan as well as former SNCC activists have illuminated the organization’s distinct style of grassroots organizing, but the geographical infrastructure and financial function of the organization’s national network has received less scholarly attention.4 Between 1961 and 1965, SNCC’s national office in Atlanta developed a sophisticated and flexible network of campus and community groups across the United States that supported the organization’s work in the deep south. James Forman and Bob Moses, two SNCC staff members, described the national network of “Friends Chapters” as a “tree.”5 I use mapping software to visualize the network’s economic and political geography of SNCC’s Friends Network. This spatial analysis of SNCC’s national network and social demographics reveals the ways the organization created a bridge between the racial and economic worlds of the United States in the 1960s. In this way, SNCC’s grassroots organizing was more than a “local” effort; it was also a national effort that linked local concerns to raising the political consciousness of citizens north of the Mason-Dixon line.

Students and staff in SNCC were deeply committed to what historian Charles Payne defines as the African American Community Organizing Tradition. In contrast to the community mobilizing practices more popularly remembered in such events as the March on Washington, that organizing tradition emphasized the long-term development of leadership in ordinary men and women. Ella Baker, an adult mentor to SNCC students, personified the organizing tradition. Working in the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Council in the 1940s and 1950s, Baker committed to the slow organizing work of day-to-day meetings—what she defined as “spadework”—to cultivate community leadership. Baker believed that the populations most marginalized by the political and economic system had the knowledge and capacity to change the system. At the same time, Baker also recognized the need to organize in communities that were the complete opposite, that is, among communities that benefited from the political and economic system. While Baker clearly understood that the Northern white liberal or the charismatic preacher were hardly models of progressive social change, she also knew that they could make an important contribution to the movement.6

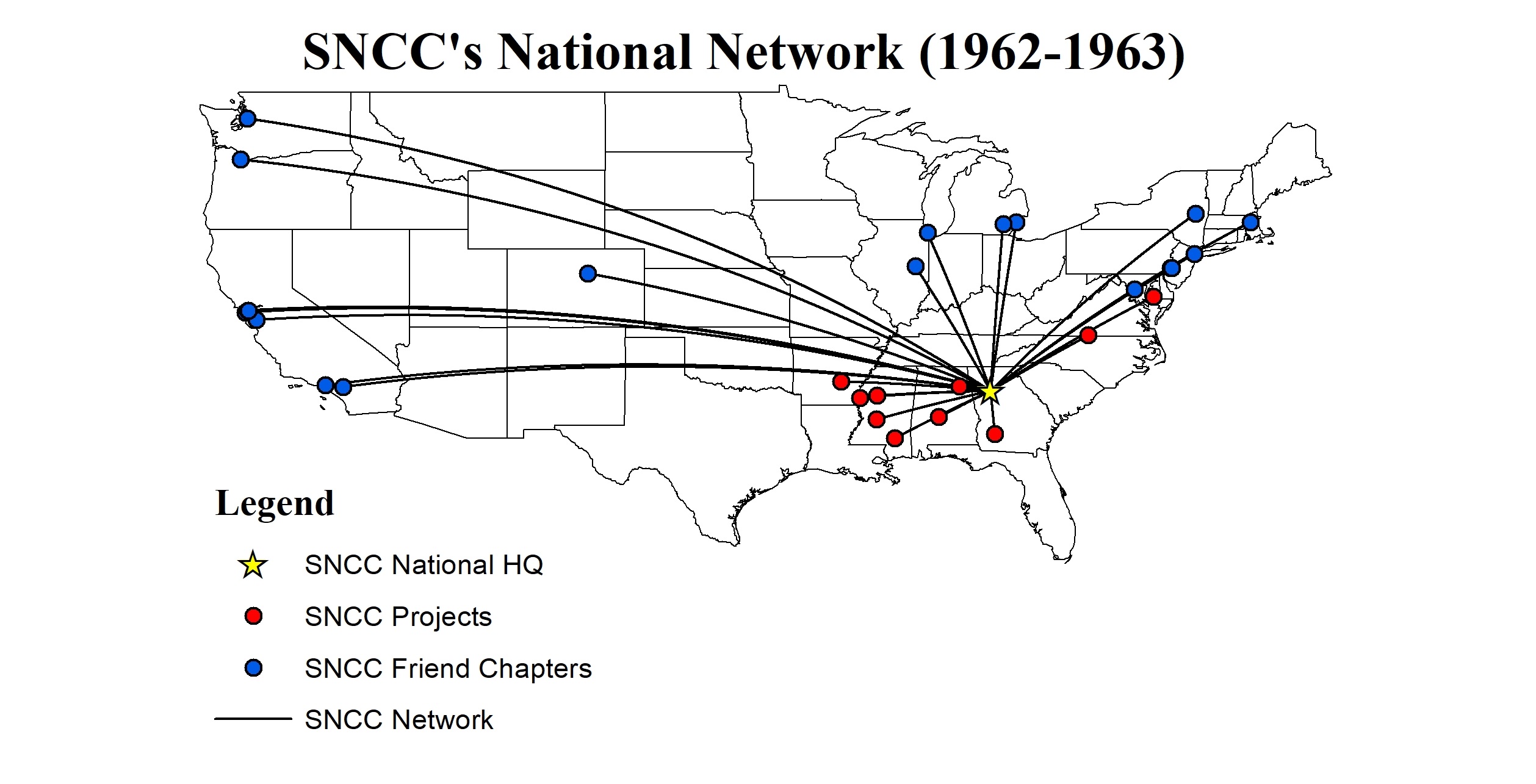

Baker’s organizing philosophy influenced SNCC’s fundraising strategy. From 1962 to 1963, SNCC students developed “Friends of SNCC” chapters around the United States. As Figure 1 shows, Atlanta, Georgia, where SNCC was headquartered, served as a fulcrum between the organization’s projects in the South and fundraising efforts in the North. The chapters linked fundraising and food drives to the community organizing tradition that emphasized political education and participation. “We in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee look on Northern Support as more than fundraising: we want to find a way for concerned individuals and groups outside the South to play a role in creating racial justice in the South,” SNCC staff explained to Northern supporters. SNCC fieldworkers underscored that “each fund raising [sic] drive should be seen as an educational effort also, for change in the South depends on a climate of opinion all over the country which will cause people to support the movement in the South and demand action from the Federal government.”7 The “Friends of SNCC” chapters maintained a commitment to grassroots organizing in the Black Belt and poor communities in the America South while also translating that organizing strategy in the context of wealthy homes of Martha’s Vineyard and Hollywood.

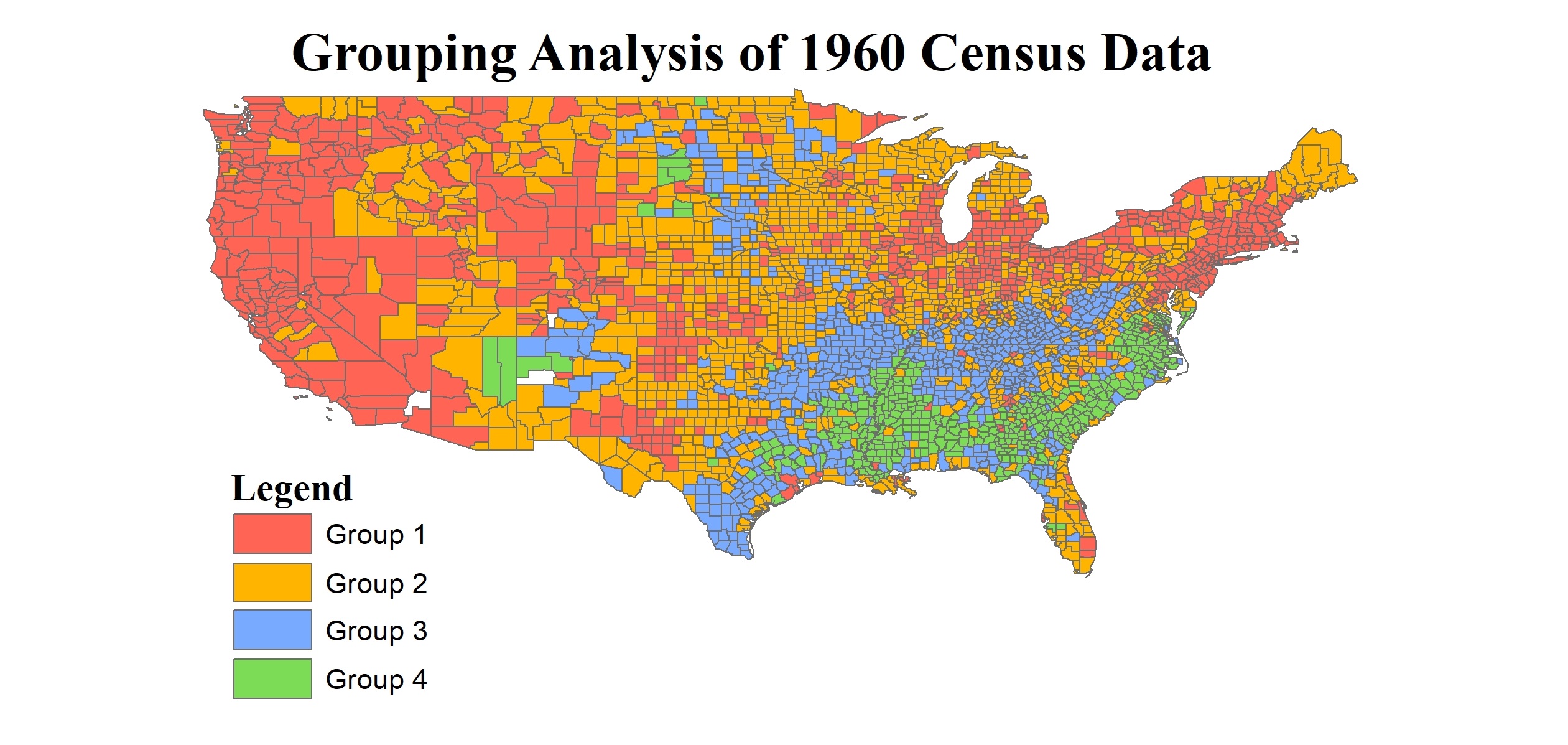

U.S. Census records on 1960 poverty data, racial characteristics of the population, per capita income, and median family income at the county level reveals the economic significance of the network. The four census datasets provide a lens onto the general racial and economic character of a given community. I visualized the data at the county level and used grouping analysis to create four distinct categories based on the natural cluster of the data.8 As figure 2 shows, the grouping analysis of 1960 census data reveals that the American south had the highest rates of poverty and highest percentage of population defined as “nonwhite” per 1960 nomenclature while also having the lowest per capita and median family income. This should not come as a surprise: the data visualizes the economic effects of Jim Crow and racial segregation.

| Category | Group #1 | Group #2 | Group #3 | Group #4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average % of Population Below the Poverty Line | 16.42% | 29.88% | 49.78% | 58.78% |

| Average % of Population Defined as “Non-White” | 4.29% | 5.12% | 7.58% | 47.57% |

| Average Median Family Income of Population | $5836.10 | $4306.94 | $2874.92 | $2744.58 |

| Average Per Capita Income of Population | $1891.30 | $1384.03 | $971.99 | $863.84 |

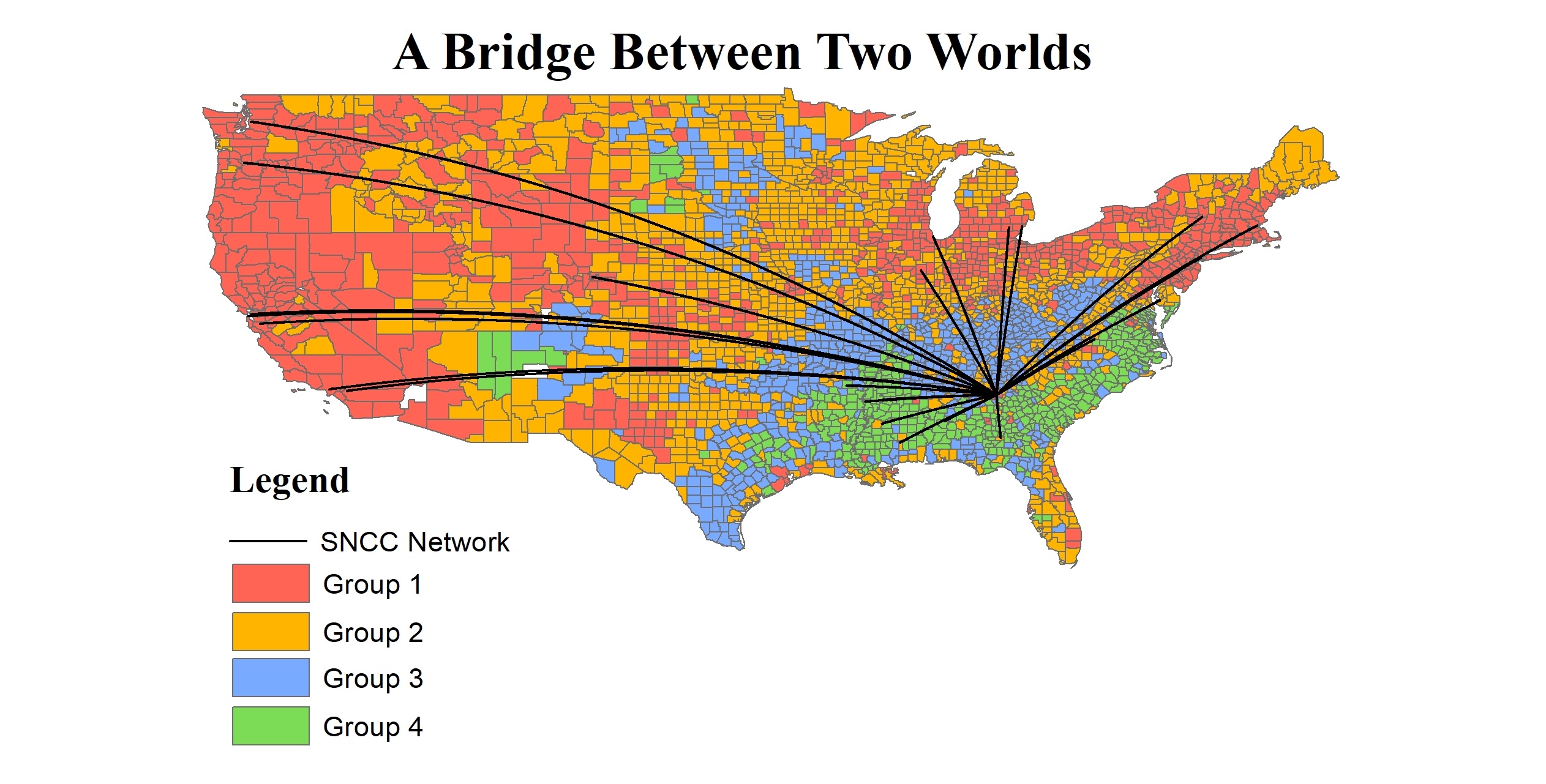

SNCC’s multi-tiered fundraising strategy is evident when the organization’s network of projects and Friend chapters is overlaid on the 1960 Census data, as shown in figure 3.9 On a national scale, SNCC’s Friends Network enabled the organization to draw on the financial resources in the North to support their work in the South. The main Friends Chapters in 1963 were all located in group 1, or areas of the country with lower poverty rates and where the Median Family Income and the Per Capita Income were twice the level of the areas where SNCC projects were located. In this way, the organization established strategic projects focused on political empowerment in counties deeply shaped by segregation and Jim Crow while also developing connections in Northern counties that had the economic and political power to support their organizing efforts. Spatial analysis, as seen in figure 3, reveals both the economic divide between the North and South in the 1960s and the ways SNCC developed a bridge that linked Northern financial resources to the civil rights struggle in the South. Bob Moses and James Forman recognized the significance of the connections when describing SNCC as a tree. “The little small tree,” they explained, “got its sunshine (which could be money) from the North, and its rain from the South, in the presence of Southern students who helped to develop these roots which are now in the communities.”10

| Category | Group #1 | Group #2 | Group #3 | Group #4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Projects | 1 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| Number of Chapters | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The spatial analysis of SNCC’s National Network reveals new areas for research on SNCC. The first area is SNCC’s transregional activism. In addition to fundraising, Friends of SNCC Chapters were also on the forefront of civil rights struggles in Northern cities. Lawrence Landry, who formed the Chicago Friends of SNCC, played a central role in the 1963 Chicago School Boycott, when close to 225,000 students walked out of school to protest school segregation. Examining the work of SNCC Friends chapters will further illuminate the civil rights struggles that extended beyond the Mason-Dixon line as well as the unique political dynamics that influenced and constrained efforts in the North.11 The second area is the vital role of SNCC Friends Chapters in the recruitment of students and other volunteers. The 1964 Freedom Summer has been the subject of extensive scholarship.12 Yet, scholars have not demonstrated how SNCC was able to recruit close to 1,000 students from across the United States. Early research on the location of SNCC Friends Chapters shows that 65% of the chapters were located on or near college campuses. Moreover, linking the Friends chapter locations with where the summer volunteers traveled from will reveal the strategic significance of SNCC Friends Chapters in the recruitment of lawyers, ministers, students, and teachers from across the United States. Future work will integrate other elements of spatial analysis, digital archiving (oral histories), and deep mapping to illuminate SNCC activism in Northern cities and recruitment.

The digital methodologies used for this project offer new tools of analysis for historians and scholars of social movements. Digital historians have used spatial analysis to reveal the ways federal and state policies structurally embedded class, gender, and racial inequalities in the American economic and political system.13 Other historians have turned to digital technologies to map and archive the locations of sit-ins, protests, and related activities associated with the civil rights movement, labor unions, student activism, and women suffrage.14 Combining both forms of digital research makes it possible to critically examine the political and economic importance of protest and organizing location and the sophisticated tactics that activists employed to address deeply rooted inequalities.

Bibliography

Carson, Clayborne. In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1981.

Dittmer, John. The Good Doctors: The Medical Committee for Human Rights and the Struggle for Social Justice in Health Care. Oxford, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2009.

Donaldson, Ivanhoe. Interview by Rachel Reinhard. September 20, 2003. Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage, University of Southern Mississippi. https://digitalcollections.usm.edu/uncategorized/digitalFile_6a1ac596-9e61-45ca-b18b-08de00781cba/.

Hale, Jon. The Freedom Schools: Student Activists in the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.7312/hale17568.

Hogan, Wesley. Many Minds, One Heart: SNCC’s Dream for a New America. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

McAdams, Douglas. Freedom Summer. Oxford University Press, 1988.

Nelson, Robert K., LaDale Winling; Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly, et al. “Mapping Inequality.” American Panorama. Edited by Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/.

Payne, Charles. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Traditionand the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1995.

Pertilla, Atiba. “Mapping Mobility: Class and Spatial Mobility in the Wall Street Workforce, 1890–1914,” Current Research in Digital History 1 (2018). https://doi.org/10.31835/crdh.2018.06.

Ransby, Barbara. Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Raymond, Emile. Stars for Freedom: Hollywood, Black Celebrities, and the Civil Rights Movement. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2013.

Rothschild, Mary. A Case of Black and White: Northern Volunteers and Southern Freedom Summers. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982.

Stefani, Anne. Unlikely Dissenters: White Southern Women in the Fight for Racial Justice, 1920–1970. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2017.

SNCC Digital Gateway team. SNCC Digital Gateway. SNCC Legacy Project, Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies, and Duke University Libraries. https://snccdigital.org.

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. “You Can Help: Support Programs for SNCC.” July 30, 1963. Civil Rights Movement Archive, Tougaloo College. https://www.crmvet.org/docs/630730_sncc_fos_help.pdf.

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. “What is SNCC?” folder 1, box 1, Samuel Walker Papers, 1964-1966, Mss 655. Archives Main Stacks, Wisconsin Historical Society.

Sugrue, Thomas J. Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North. New York: Random House, 2008.

Theoharis, Jeanne, and Brian Purnell. The Strange Careers of the Jim Crow North: Segregation and Struggle Outside of the South. New York: New York University Press, 2019.

U.S. Census Bureau. 1960 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics. March 31, 1961.

U.S. Census Bureau. Population by Poverty Status by Counties. 1959.

U.S. Census Bureau. 1960 Census of Population, Supplementary Reports: Per Capita and Median Family Income in 1959, for States, Standard Metropolitan Areas, and Counties, Full Report. July 30, 1965.

Notes

The author would like to thank the CRDH editors Stephen Robertson and Lincoln A. Mullen and the three peer reviewers for the generous feedback. The article is also shaped by insights from an ongoing digital project called The Tree of Protest, which is forthcoming.

-

Donaldson, interview. ↩

-

Raymond, Stars for Freedom. ↩

-

Raymond, Stars for Freedom; SNCC, “You Can Help.” ↩

-

Carson, In Struggle; Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom; Hogan, Many Minds, One Heart; and SNCC Digital Gateway. ↩

-

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, “What is SNCC?” ↩

-

Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom; Ransby, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement. ↩

-

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, “You Can Help: Support Programs for SNCC.” ↩

-

U.S. Census Bureau, 1960 Census of Population. ↩

-

Stefani, Unlikely Dissenters. ↩

-

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, “What is SNCC?” ↩

-

Theoharis and Purnell, The Strange Careers of the Jim Crow North; Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty. ↩

-

Rothschild, A Case of Black and White; McAdams, Freedom Summer; Dittmer, The Good Doctors; Hale, The Freedom Schools. ↩

-

Nelson et al., “Mapping Inequality”; Pertilla, “Mapping Mobility.” ↩

-

Gregory et. al., Mapping American Social Movements; SNCC Digital Gateway team, SNCC Digital Gateway. ↩

Appendices

Author

David S. Busch,

Department of History, Case Western Reserve University, dxb583@case.edu,